C.R. Henry of the South-Eastern & Chatham Railway wrote about this line being the second public railway opened in England in an article in the October 1907 edition of The Railway Magazine. [1] Reading that article prompted this look at the line which was referred to locally as the ‘Crab and Winkle Line‘.

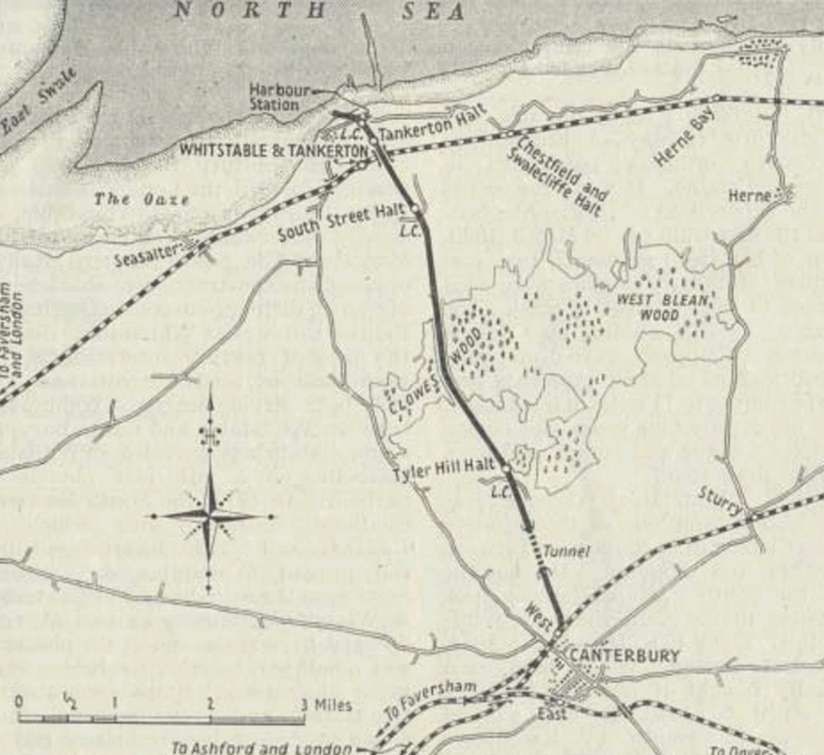

There are a number of claimants to the title ‘first railway in Britain’, including the Middleton Railway, the Swansea and Mumbles Railway and the Surrey Iron Railway amongst others. Samuel Lewis in his ‘A Topographical Dictionary of England’ in 1848, called the Canterbury & Whitstable Railway the first railway in the South of England. [2][3]

The Crab and Winkle Line Trust says that in 1830, the “Canterbury and Whitstable Railway was at the cutting edge of technology. Known affectionately as the ‘Crab and Winkle Line’ from the seafood for which Whitstable was famous, it was the third railway line ever to be built. However, it was the first in the world to take passengers regularly and the first railway to issue season tickets. The first railway season tickets were issued at Canterbury in 1834 to take people to the beach at Whitstable over the summer season. This fact is now recorded on a plaque at Canterbury West railway station. Whitstable was also home to the world’s oldest passenger railway bridge.” [17]

Henry explains that in 1822, “the possibility of making Canterbury a virtual seaport was engaging much thought and attention on the part of the inhabitants of that ancient city. Canterbury is situated on the banks of a small river called the Stour, having an outlet into the sea near Sandwich, and this river was a very important waterway in Roman and Saxon times, but by the date above-mentioned, it had fallen into a state almost approaching complete dereliction, being quite unnavigable for ships of any appreciable size. The resuscitation and improvement of this waterway was considered to be the only solution of the problem of making Canterbury a seaport, and as a result of a very strong and influential agitation by the citizens a scheme of revival was announced by a number of commercial men who had formed themselves into a company for the purpose. The scheme comprised many improvements to the river, such as widenings, new cuts, etc., with the provision of a suitable harbour at Sandwich, the estimated cost of the whole being about £45,700. It was submitted to Parliament in the session of 1824, but the Bill was rejected by a motion brought forward by the Commissioners of Sewers, who complained that the works had been hurriedly surveyed and greatly under-estimated. Nothing daunted, however, fresh surveys and estimates were prepared and presented to Parliament in the following year. This second Bill was successful, and when the news that it had passed the third reading in the Upper Chamber was made known in Canterbury, the event occasioned much jubilation amongst the inhabitants, who, according to local records, turned out with bands of music and paraded the streets exhibiting banners displaying such words as ‘Success to the Stour Navigation’.” [1: p305-306]

It is worth noting that it was as early as 1514 that an Act of Parliament promoted navigation on the River Stour. There remains “a Right of Navigation on the river from Canterbury to the sea. After two weirs above Fordwich, the river becomes tidal.” [4]

C.R. Henry continues:

“While the city was so enraptured with its waterway scheme, influences of a quieter nature were steadily at work with a view to making Canterbury a virtual seaport by constructing a railway from thence to Whitstable. One day in April 1823, a gentleman – the late Mr. William James – called on an inhabitant of Canterbury to whom he had been recommended, to consult with him on the subject of a railway. It was arranged between these two gentlemen that a few persons who it was thought might be favourable to the project should be requested to meet the next day: several were applied to, but the scheme appeared so chimerical that few attended. At the meeting the gentleman stated he had professionally taken a cursory view of the country, and he thought a railway might be constructed from the copperas houses at Whitstable (these houses used to exist on the eastern side of the present harbour) to St. Dunstan’s, Canterbury. This line, he observed, was not so direct as might be the most desirable, but there would not be any deep cutting, and the railway would be formed on a regular ascending and descend. ing inclined plane. He also urged that by the construction of a harbour at Whitstable in conjunction with the projected railway, the problem of making Canterbury an inland seaport would be effectually solved, and that the railway offered undoubted advantages over any waterway scheme in point of reliability and rapidity of conveyance, as well as being only half the length of the proposed navigation.

The railway scheme met with scant support at first, but by 1824 a few private and commercial gentlemen had been found who were willing to form themselves into a company for the prosecution of the project, and they elected to consult Mr. George Stephenson as to the feasibility of their idea. The projector of the Canterbury and Whitstable Railway, as already said, was the late William James, well-known for the part he took in the Liverpool and Manchester Railway and other lines, and it was no doubt through his influence that it was decided to consult Stephenson, with whom he was very friendly at the time. George Stephenson, however, was too occupied with larger undertakings in the North to give the Canterbury and Whitstable Railway much of his personal attention, so he deputed his assistant, Mr. John Dixon to survey the line.

George Stephenson advised that the railway be made to pass over the ground situate between the [present] tunnel through Tyler Hill and St. Thomas’s Hill onwards through the village of Blean, then to Whitstable, terminating at precisely the same spot as it now does [in 1907], this route being an almost level one, and not necessitating many heavy earthworks. But the proprietors did not behold this route with favour: they wished for the novelty of a tunnel, so a tunnel Stephenson made for them, thereby altering the whole line of railway he first proposed, and causing it to traverse some very undulating and steep country. A survey of the new route was made, which was to the right of the original one, and plans, sections and estimates were duly deposited with Parliament for the Session of 1825.

The Canterbury and Whitstable Railway Bill was not assailed with great opposition, the only body really opposing it being the Whitstable Road Turnpike Trust, who, however, were compromised by the insertion of a clause in the Bill to the effect that ‘should the project be carried into execution, the Company, when formed, will indemnify the Trust to the full amount which they may suffer by traffic being diverted, and that for 20 years’. The Act received Royal Assent on 10th June 1825.” [1: p306-307]

So it was, that work on the railway and harbour went ahead and the improvements to the Stour Navigation were left in abeyance, and the then insignificant village of Whitstable became one of the first places to have a railway.

The Company was formed with a nominal capital of £31,000 divided into £50 shares. Joseph Locke was appointed ‘resident engineer’ and a host of experienced workers (navvies) were brought down from the North of England to work on the line.

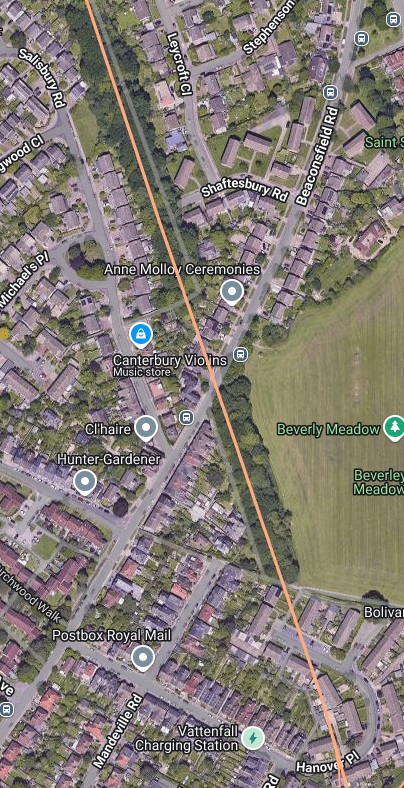

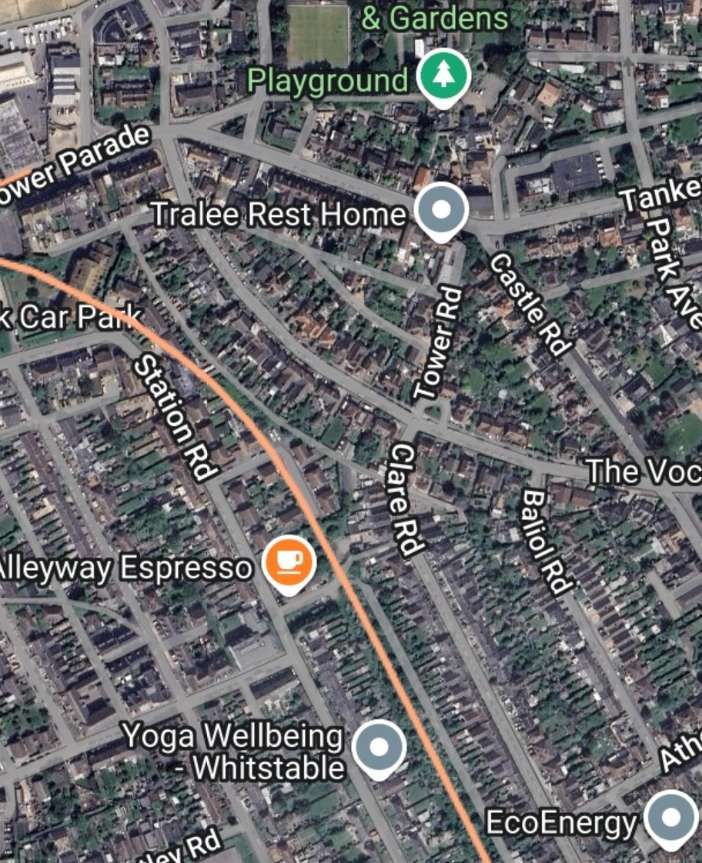

North of the railway corridor the route of the old railway, shown in pale orange, runs North-northwest. It crosses Hanover Place twice and runs ups the West side of Beverly Meadow. The route is tree-lined as far as Beaconsfield Road. A footpath runs immediately alongside to the route. That footpath appears as a grey line on the satellite imagery adjacent to this text.

North of Beaconsfield Road the line of the old railway has been built over – private dwellings face out onto the road. North of the rear fences of these properties a tree-line path follows fairly closely the line of the old railway between two modern housing estates as far as the playing fields associated with The Archbishop’s School. [15]

C.R. Henry continues:

“The Canterbury and Whitstable Railway was laid out with gradients almost unique in their steepness, necessitating the major portion of the line being worked by stationary engines. At Canterbury the terminus was situated in North Lane, whence the railway rises in a perfectly straight line on gradients ranging between 1 in 41 and 1 in 56, to the summit of Tyler Hill, a distance of 3,300 yards.

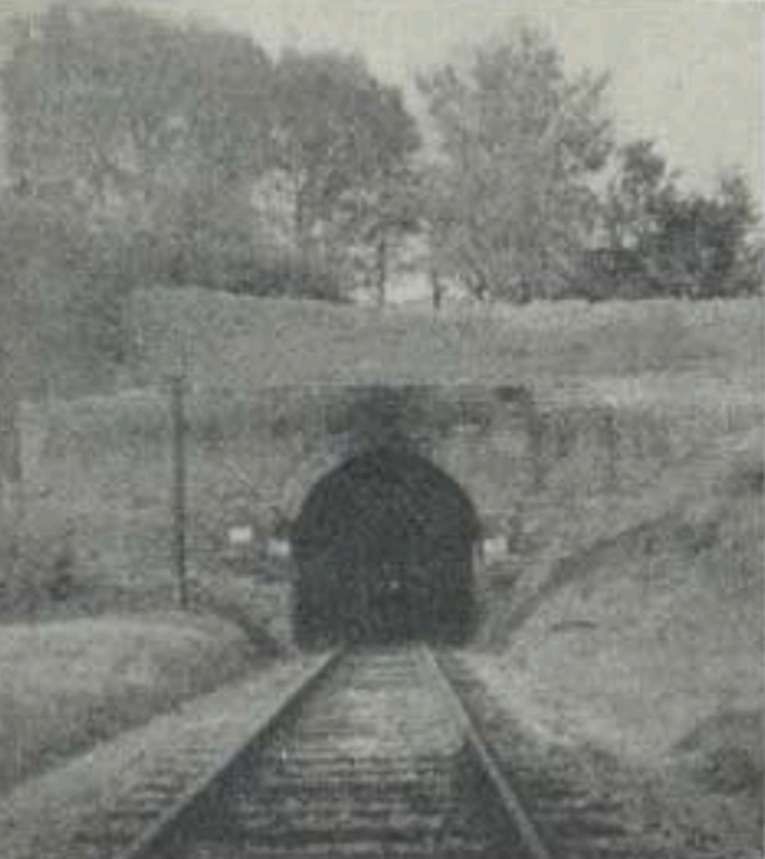

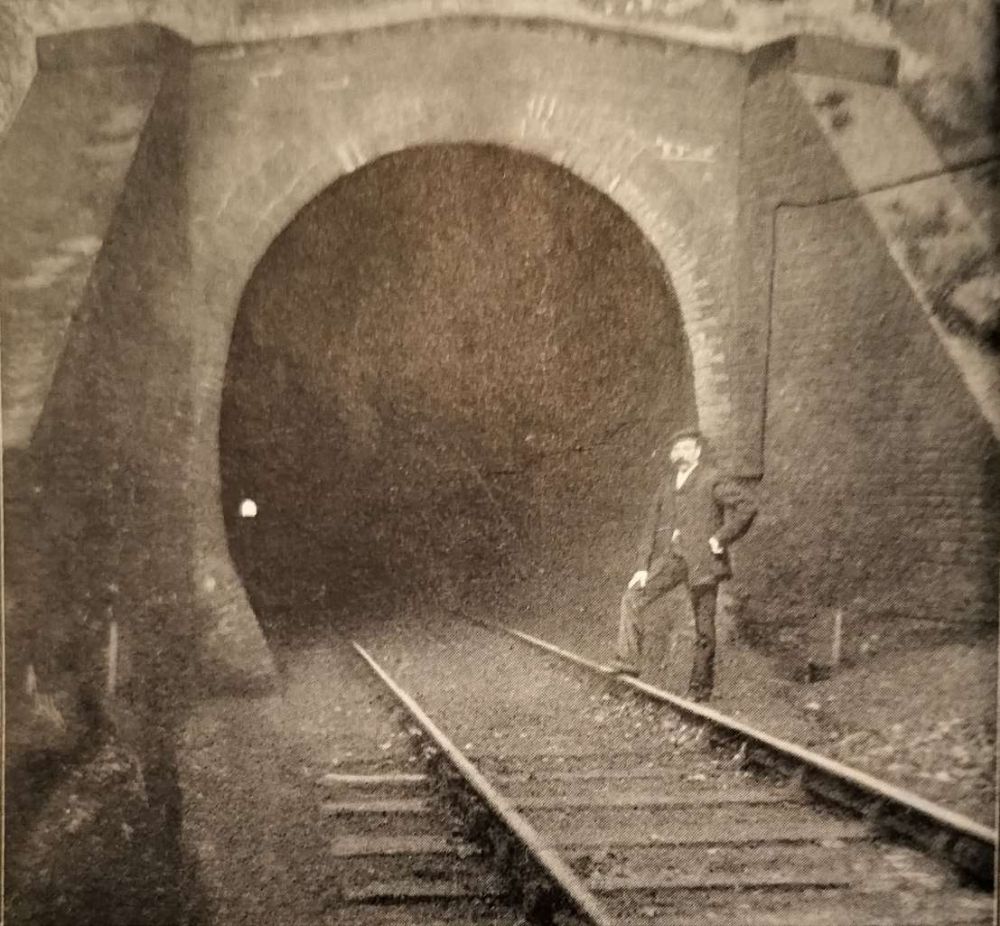

On this section is the Tyler Hill tunnel which the proprietors were so anxious to have. This peculiar little tunnel may be termed the principal engineering feature of the Canterbury and Whitstable Railway: it is half a mile long, and was constructed in four different sections, each of varying gauge. The working face evidently started at the Whitstable side of Tyler Hill, since as it advances towards Canterbury each section becomes larger than the preceding one. The first three sections are the usual egg shape, but the final section, i.e., at the Canterbury or south end, has perpendicular instead of bow walls, and is the largest of the four. In the very early days the Canterbury end of the tunnel was closed at nighttime by wicket gates, and the rides upon which the gates hung are still to be seen in the brickwork. The bore of the tunnel is unusually small specially constructed rolling stock having to be used for the present day passenger service over the line.” [1: p309]

Tyler Hill Tunnel runs underneath the Canterbury Campus of the University of Kent. Its South Portal was adjacent to the Archbishop of Canterbury’s School at the bottom-right of the adjacent satellite image. [15]

Giles Lane appears on both the early OS map extract and this satellite imagery. [8][15]

The North portal of the tunnel is highlighted by a lilac flag on the adjacent satellite image. [15]

Two photographs below show North Portal as it is in the 21st century. It is fenced and gated for safety and security purposes. The first shows the spalling brickwork of the tunnel ring, and the boarding-off of the entrance provided with an access gate. for maintenance purposes. Both were shared on Google Maps.

Henry continues his description of the line:

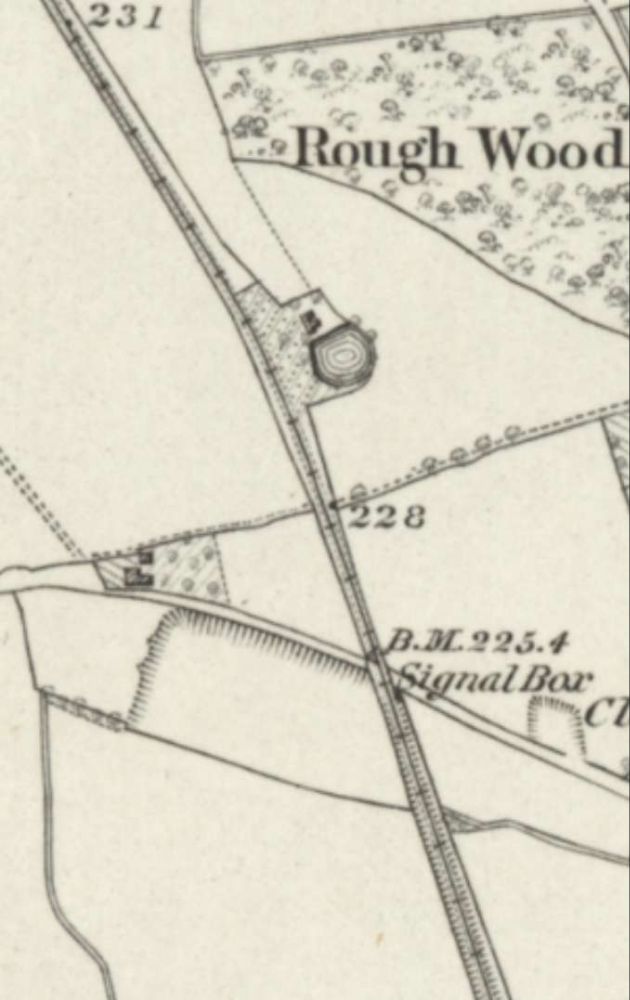

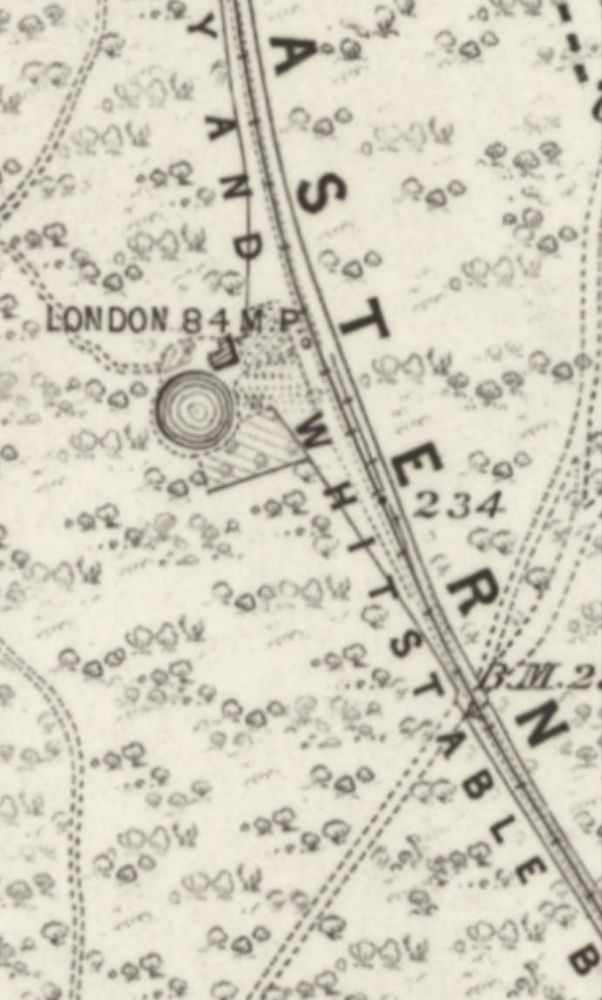

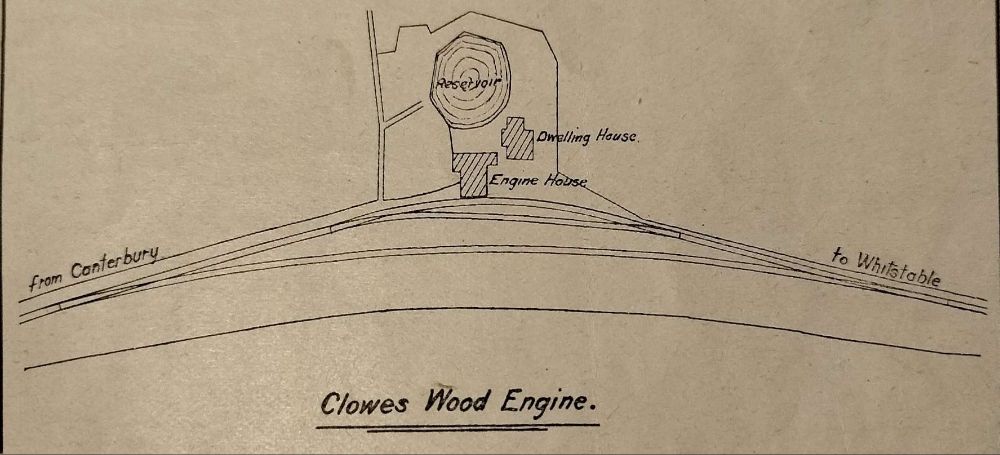

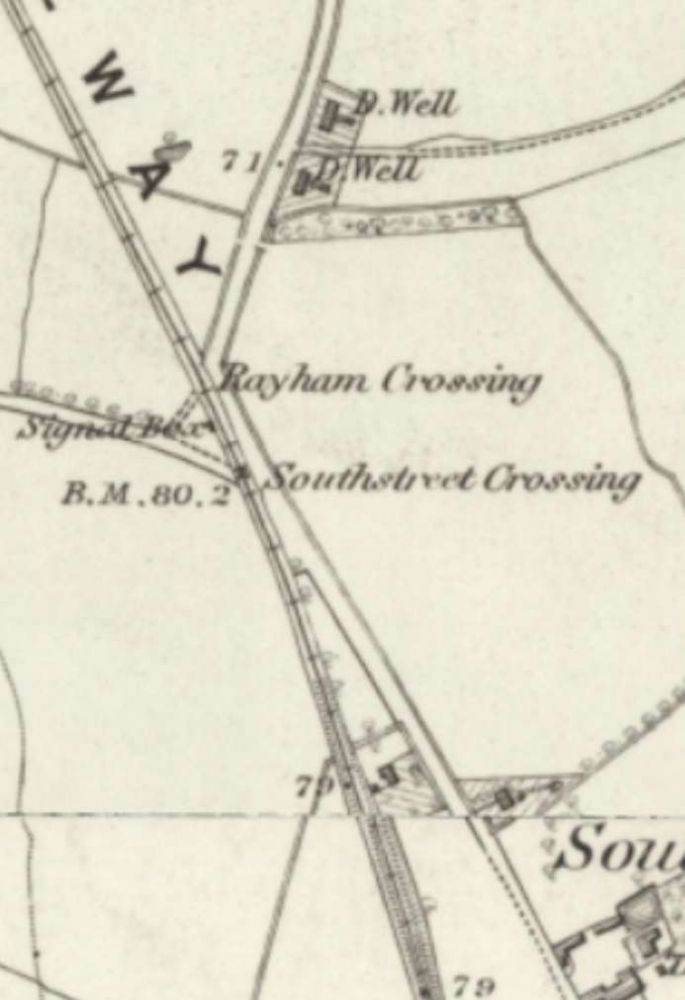

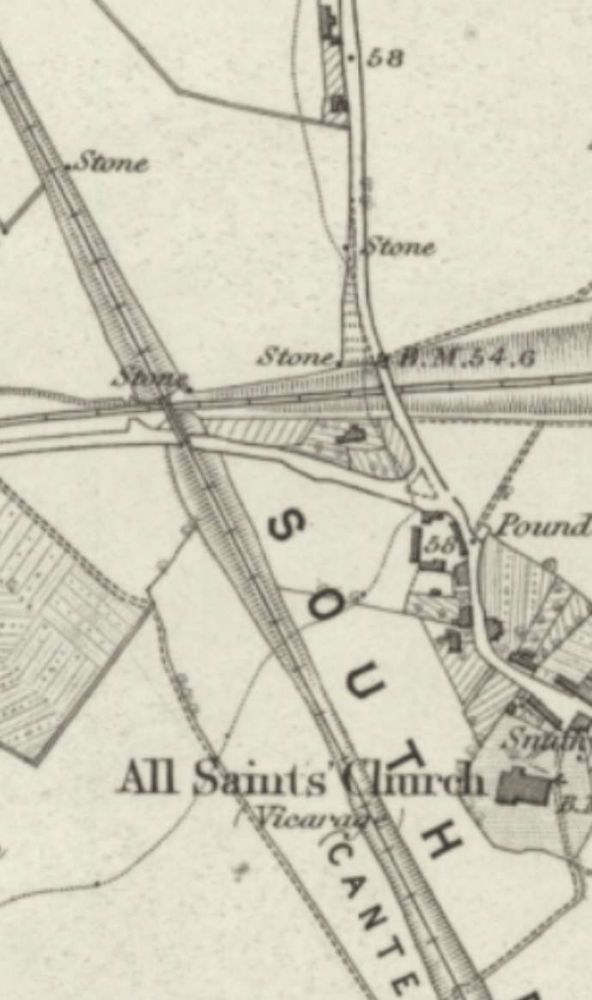

“At the top of the steep bank from Canterbury there stood two 25 h.p. stationary engines for winding the trains up the incline. From where the first engine house stood the line is straight and practically level for the next mile to Clowes Wood summit, where there were two fixed engines of the same type and h.p. as those at the previous stage. The line then descends at 1 in 28 and 1 in 31 for the next mile to a place called Bogshole, so named owing to the once spongy condition of the ground in the vicinity, which was a constant source of trouble during the early days of the railway, as whenever wet weather set in the track invariably subsided with sometimes consequent cessations of traffic for a whole day, and even longer. At Bogshole commences the South Street level, which continues for a mile to the top of Church Street bank, whence the line again falls for half a mile at 1 in 57, the remaining half mile to Whitstable being almost at level.” [1: p310]

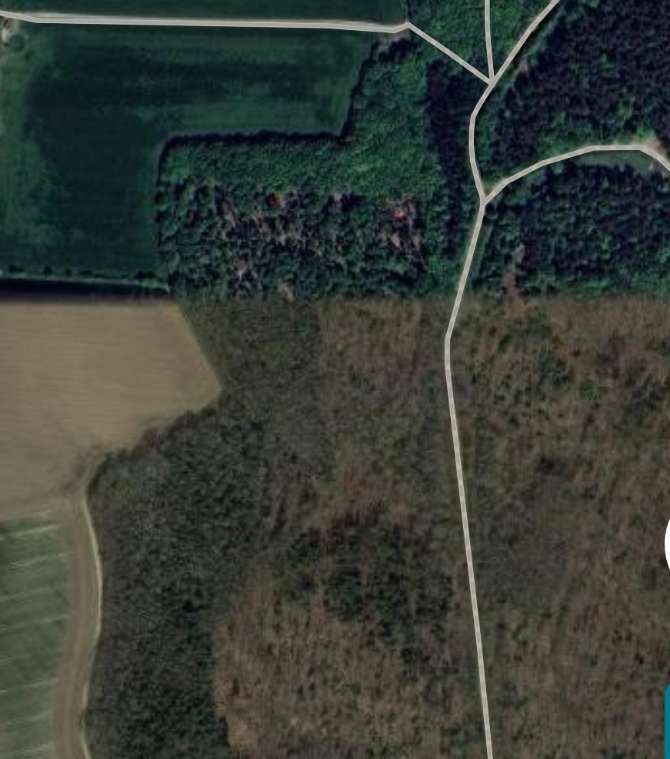

The two extracts from railmaponline.com’s satellite imagery above show the route of the old line as it runs down across the line of the modern A299 (at the top of the first image and at the bottom of the second image). In each case, if you cannot see the full image, double-click on it to enlarge it. For the majority of this length the old railway line followed a straight course. [15]

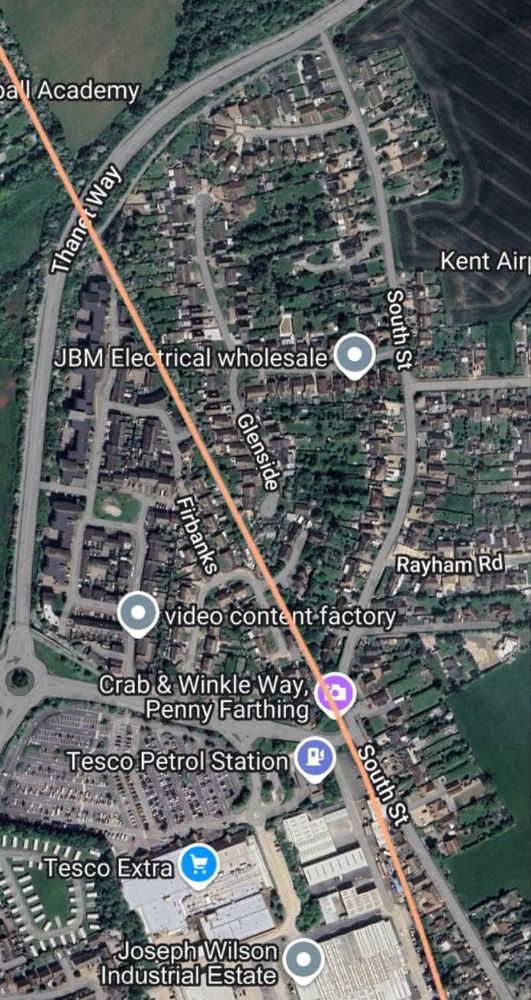

The old railway route continues North and after passing through the rear gardens of houses on South Street runs, for a short distance immediately adjacent to South Street.

Henry comments:

“Just below the top of Church Street bank is situated the only public road bridge on the railway. This is a narrow brick arch spanning Church Street, and stands today in its original form, notwithstanding the several but fruitless efforts of the local traction engine drivers to affect its displacement with their ponderous machines.” [1: p310]

The bridge to which Henry refers is long-gone in the 21st century. We can still, however, follow much of the route of the old railway.

Henry continues his account:

“Before the completion of these works, … the company had twice to recourse to Parliament for additional capital powers, having exceeded those already granted with the railway in a half-finished state. The first was in 1827, when it was stated that the works authorised in 1825 had made good progress, but for their successful completion a further sum of money to the tune of £19,000 would be required, and for which they now asked. This Act also empowered the company to become carriers of passengers and goods, their original intention being to only levy tolls on all wagons and carriages passing over their line, the railway company providing the tractive power. The Act received royal assent on 2nd April 1827, but the larger portion of it was repealed by another in following year, the directors having found that the £19,000 previously authorised would prove inadequate for their purpose; so in 1828 they again went to Parliament for powers to raise £40,000 in lien thereof, and also petitioned for powers to lease the undertaking should they so desire, for a term not exceeding 14 years. These powers were conceded, and the Act received Royal Assent in May 1828. … The capital of the company aggregated £71,000 before the opening of the railway took place, which sum was further increased by a subsequent Act. … By May 1829, the works were nearing completion [and] … the question of permanent way and the gauge to which it was to be laid, had to be [considered.] … The Stephenson gauge of 4 ft. 8 1/2 in, was adopted. The permanent way … was laid with Birkenshaw’s patent wrought-iron fish-bellied rails and castings, of which George Stephenson highly approved. These rails were rolled in lengths of 15 ft. and weighed 28lb to the yard. The castings were spiked to oak sleepers placed at intervals of 3 ft., and the sheeves upon which the winding ropes of the stationary engines ran were situated in the centre of the track fixed to the sleepers at intervals of 6 ft.” [1: p310-311]

Henry continues:

With “all earthworks completed, engine houses, engines and stationary engines erected, permanent way laid, and everything generally ready to be brought into use, excepting the harbour, which was not completed for a year or two later, the Company announced the formal opening of the railway for 3rd May 1830.” [1: p311]

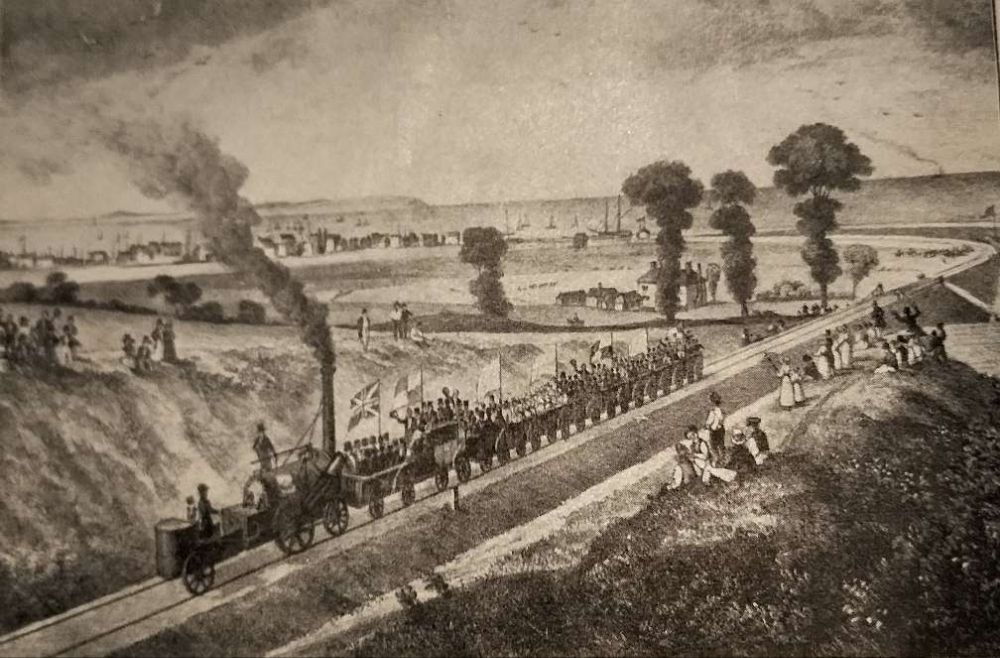

Of that day in 1830, the Kent Herald wrote:

“The day being remarkably fine, the whole City seemed to have poured forth its population, and company from the surrounding country continuing to augment the throng. By eleven o’clock, the time appointed for the procession to start, the assemblage of spectators was immense. The fields on each side of the line of road being crowded by well-dressed people of all ages, presented one of the most lively scenes we have witnessed for some time. The arrangements were so judiciously made, that by a quarter past eleven the procession was set in motion, the signal for starting having been given by telegraph. The bells of the Cathedral rang merrily at intervals during the day, and flags were displayed on the public buildings and railway. The following is the order of the procession:

1. Carriage with the directors of the Railway Company wearing white rosettes.

2. A coach with the Aldermen and other Members of the Canterbury Corporation.

3. A carriage with ladies.4. A carriage with a band of music.

5. Carriages with ladies.

6 to 20. Carriages containing the Proprietors of the Railway, their friends, etc., in all amounting to near three hundred.The procession was drawn forward in two divisions until it arrived at the first engine station, in which manner also it entered Whitstable, preceded by the locomotive engine. The various carriages contained nearly 300 persons, consisting of the principal gentry, citizens, and inhabitants of Canterbury and its neighbourhood. At Whitstable an excellent lunch was provided for the company by the Directors at the Cumberland Arms.” [14]

The Kent Herald continues:

“On returning, the procession was joined at the Engine Station, and the whole went forward into Canterbury together.

The motion of the carriages is particularly easy and agreeable, and at first starting the quiet power with which the vast mass was set in motion dispelled every fear in the passengers. The entrance into the Tunnel was very impressive – the total darkness, the accelerated speed, the rumbling of the car, the loud cheering of the whole party echoing through the vault, combined to form a situation almost terrific – certainly novel and striking. Perfect confidence in the safety of the whole apparatus

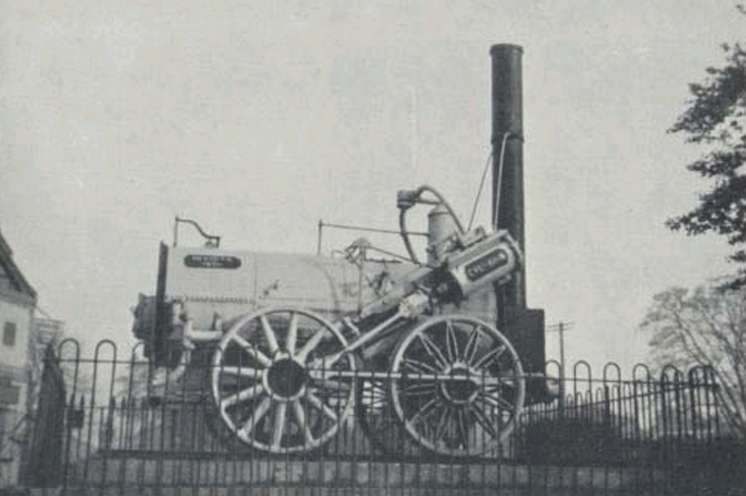

The Crab and Winkle Line Trust tells us that the locomotive that pulled that first passenger train on the line was ‘Invicta’. They go on to say that the ‘Crab and Winkle Line’ became:

“the ‘first regular steam passenger railway in the world’ as stated in the Guinness Book of Records. … The ‘Invicta’ was based on Stephenson’s more famous ‘Rocket’ which came into service four months later on the Liverpool to Manchester line. Unfortunately with just 12 horse power the ‘Invicta’ could not cope with the gradients and was only used [regularly] on the section of line between Bogshole and South Street. The rest of the line was hauled by cables using steam driven static winding engines at the Winding Pond in Clowes Wood and the Halt on Tyler Hill Road. The Winding Pond also supplied water to the engines. … By 1836 the ‘Invicta’ was replaced and a third winding engine was built at South Street. The line was a pioneer in railway engineering using embankments, cuttings, level crossings, bridges and an 836 yard (764 metre) tunnel through the high ground at Tyler Hill. The railway was worked with old engines and ancient carriages always blackened by soot from the journey through the tunnel. It was said that goods trains tended to slow down for their crews to check pheasant traps in the woods and to pick mushrooms in the fields.”

“Journey times in the 1830s were approximately 40 minutes, but by 1846 with improvements to both the line and the locomotive, the trip took just 20 minutes. This is a very respectable time especially when compared with today’s often congested roads. … In 1839, the ‘Invicta’ was offered for sale as the three stationary engines were found to be adequate for working the whole line. The one enquiry came to nothing and the locomotive was put under cover. In 1846, The South Eastern Railway reached Canterbury and acquired the Canterbury and Whitstable Railway in 1845. The branch was relaid with heavier rail and locomotives replaced the stationary engines. For many years the ‘Invicta’ was displayed by the city wall and Riding Gate in Canterbury. The ‘Invicta’ is now displayed in the Canterbury museum.” [17]

A later article about the Canterbury & Whitstable Railway, written by D. Crook, was carried by The Railway Magazine in February 1951. [19]

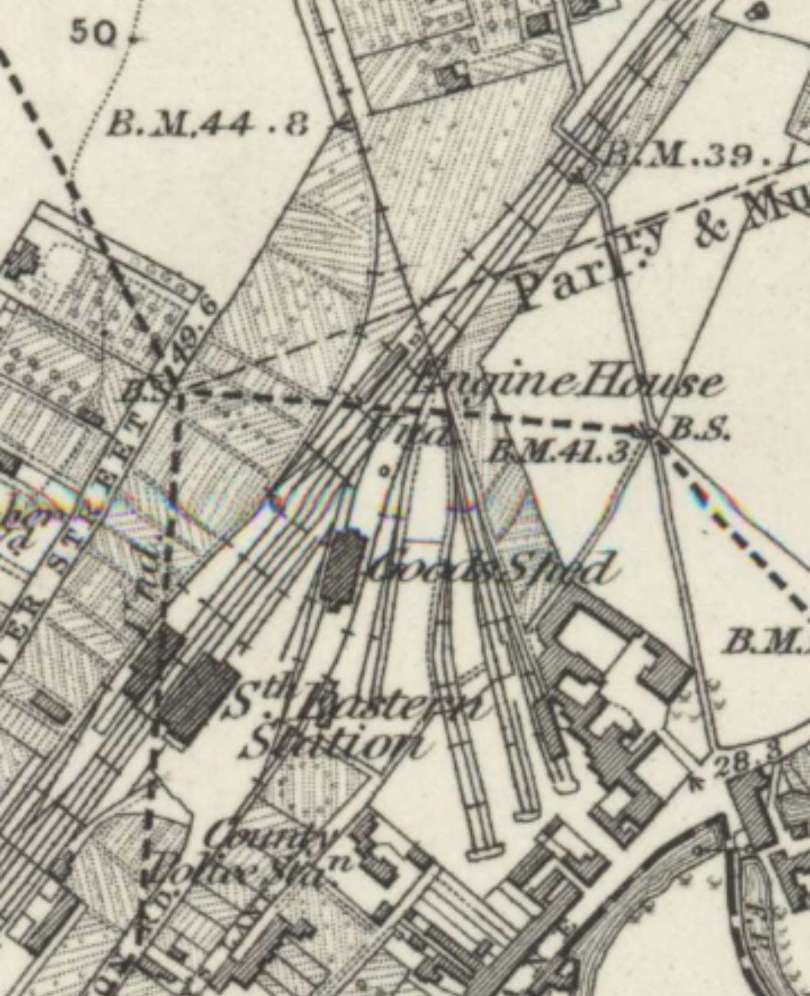

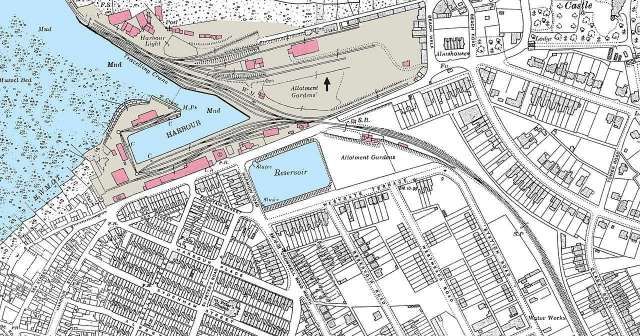

Crook says that the Canterbury & Whitstable was “the first railway in England to convey ordinary passengers in steam-hauled trains. … In 1832, Whitstable Harbour was opened and … a steamer later ran … between Whitstable and London. During the 1840s, the South Eastern Railway took an interest in the Canterbury & Whitstable line. The S.E.R. leased it in 1844, commenced working it in 1846, and eventually bought it outright in 1853. From 6th April 1846, it was worked throughout its length by locomotive traction, when a junction was made at Canterbury with the South Eastern line from Ashford to Margate.” [19: p125] It was at this time that the stationary engines became surplus to requirements.

“The financial receipts improved steadily and throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century the line was prosperous. In 1860, the London, Chatham & Dover Railway reached Whitstable, and shortly afterwards was extended to Margate. The South Eastern Railway opposed the construction of this line and, of course, there was no connection between the two railways at Whitstable. Early in the [20th] century intermediate halts were built at South Street, and Tyler Hill, both serving scattered communities between Whitstable and Canterbury, and a new station was provided at Whitstable Harbour, on a site just outside the harbour. In 1913, the South Eastern & Chatham Railway, into which the L.C.D.R. and S.E.R. had merged, built the present Whitstable & Tankerton Station on the main line. The Canterbury & Whitstable Railway crossed over this line just beyond the end of the platforms, and a halt was built on the bridge at the point of crossing. Steps connected the two stations and special facilities, such as cheap day tickets between Herne Bay and Canterbury via Whitstable, were commenced. After the first world war, local bus competition became intensive and the inevitable decline followed. In 1930, it was decided to close the line to passengers and the last passenger train ran on 31st December of that year. This decision must have brought the Southern Railway more relief than regret, for, in consequence of the one tunnel (Tyler Hill) on the route, clearances are very limited, and only selected engines and special coaching stock can work over it. From 1931 onwards the line has been used regularly for goods traffic, and today [in 1950], with total closure a possibility in the near future, it provides a wealth of interest.” [19: p125-126]

In 1950, Crook took his own journey along the Canterbury & Whitstable Railway which began at “Canterbury West Station, the bay platform from which the Whitstable trains ran [was] now disused. The railway [curved] sharply towards Whitstable, and immediately [left the main] line. The single track [climbed] up through the outskirts of Canterbury, and [entered] the first railway tunnel to be built in the world.” [19: p126]

We need to pause for a moment to note that Tyler Hill’s claim was actually to being the first tunnel which passenger services passed through. (Haie Hill Tunnel in the Forest of Dean was an earlier structure but was only used for goods services.)

Tyler Hill Tunnel restricted the dimensions of locomotives and rolling-stock on the line. Nothing wider than 9ft. 3in. or higher than 11ft. could work through the tunnel which was nearly half a mile in length. The gradient through the tunnel (1 in 50) continued North of the tunnel for a total length of two miles.

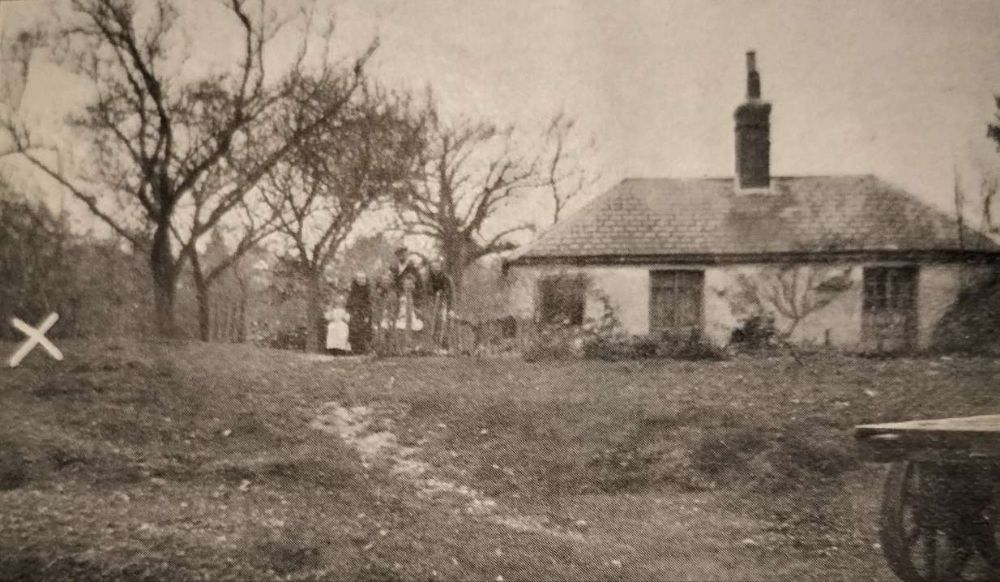

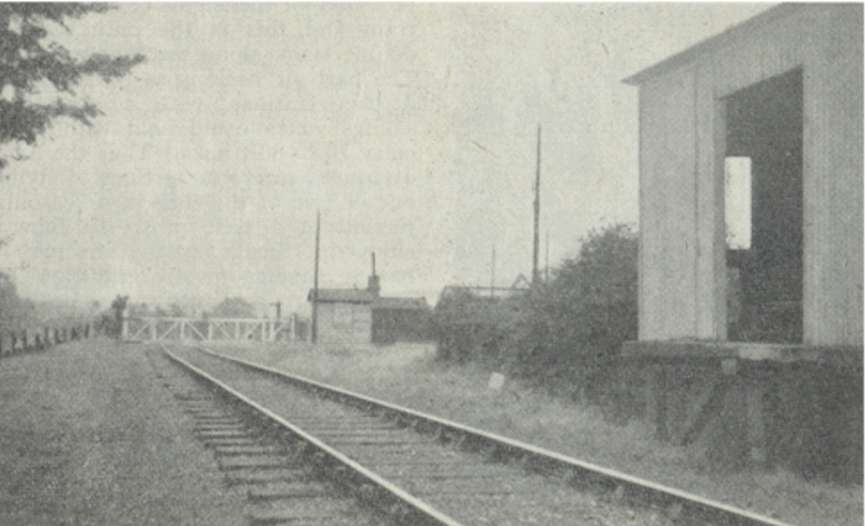

Crook mentions passing Tyler Hill level crossing but noted that there was no sign of the passenger halt which once stood there. He continues: “Entering woodland country, the line … begins to drop sharply towards Whitstable. The gradients on the descent have been widely quoted as 1 in 31 and 1 in 28, but [Crook notes] the gradient boards [he saw] show them as 1 in 32 and 1 in 30. In any case, they are among the steepest to be found on a British railway. At the foot of this bank, the woods are left behind and another level stretch follows: it was at this point that Invicta used to be coupled on to the trains. The line then approaches South Street Halt, of which the platform has been removed and the waiting room only remains. The level crossing gates there, and similarly at Tyler Hill, are operated by the resident of a nearby house, the train indicating its approach by prolonged whistling. Nearing the outskirts of Whitstable, the line passes under an imposing road bridge built in 1935 by the Kent Kent County Council and carrying the A299 road which takes the bulk of the road traffic to the Kent coast. … The final steep drop into Whitstable is at 1 in 57 and 1 in 50. A road is crossed on a picturesque brick arch, which is still in its original condition, although it is undoubtedly awkward for road traffic because of its narrowness and oblique position. Immediately beyond this bridge is a much more modern one carrying the railway over the main Victoria-Ramsgate line at a point (as mentioned earlier) just clear of the main line Whitstable Station. Not a trace remains of Tankerton Halt.” [19: p126-127]

“By 1914, the railway was running regular services for day-trippers and Tankerton was becoming a thriving tourist destination, with tea shacks and beach huts springing up along the coast. 1914 also saw the outbreak of WW1 and the Crab and Winkle Railway was passed into the hands of the Government for the next 5 years. Passenger services were halted and the railway and harbour were used to transport much needed resources to the Western Front. These included livestock, horses, ammunition and trench building equipment.” [18] After the war, the return of passenger services did not result in the same level of patronage as before the war.

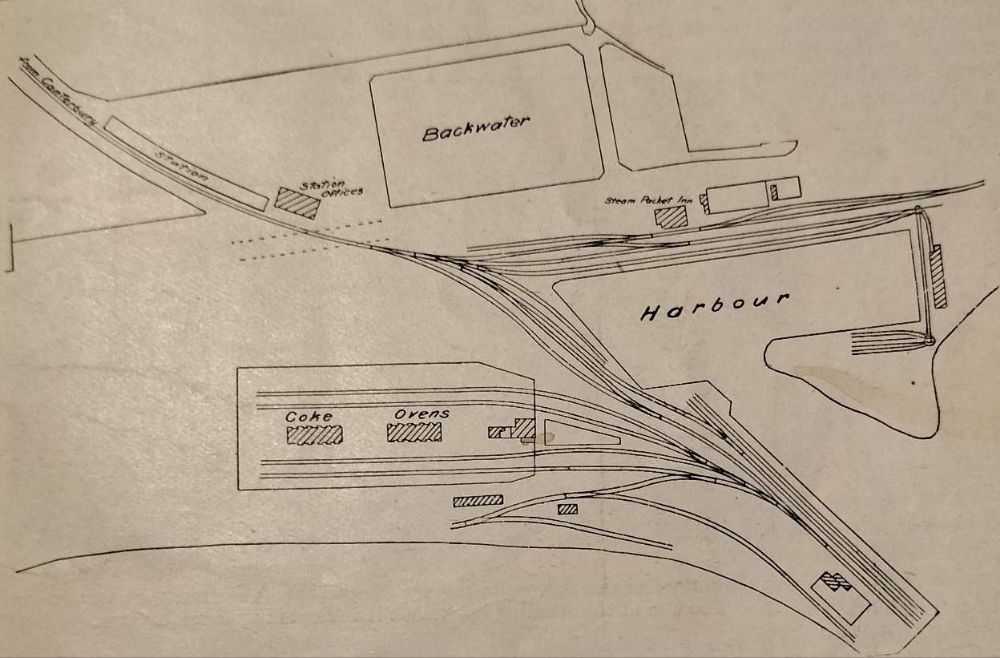

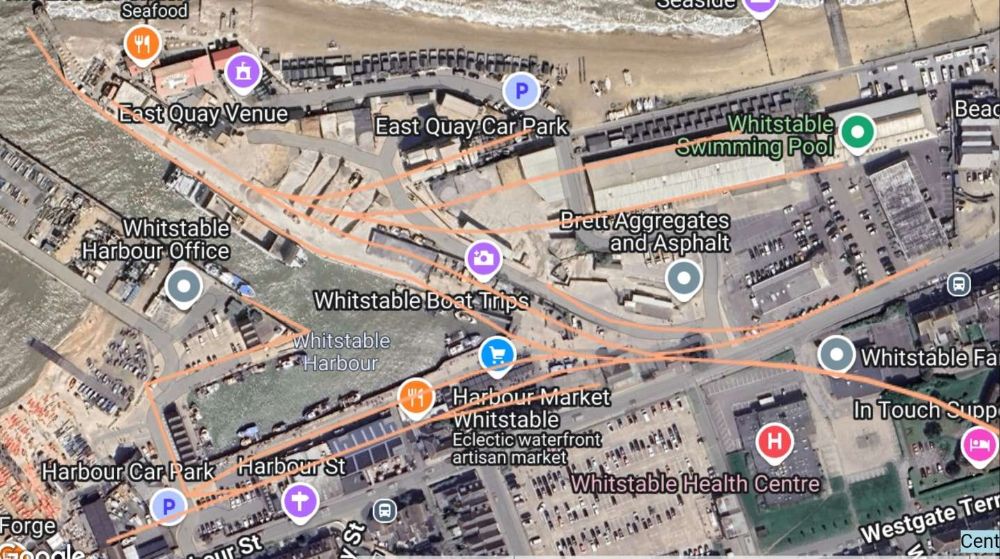

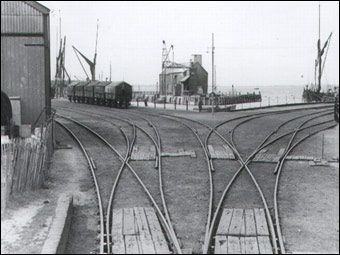

Crook continues his 1950s commentary: “Half a mile on lies the harbour, from the railway viewpoint, a pathetic sight. Both stations are still standing, the original inside the harbour gates, and the later one just outside and separated from the harbour by the main road through Whitstable. Level-crossing gates are provided there. The original station is completely derelict, and the later station, now closed for over 20 years, from the outside at least, is little better. This building has been leased for various purposes, and at present is the headquarters of the local sea cadets. Devoid of paint, and with the platform surface overgrown with weeds, it makes a very sad commentary on the march of time. The small signal box which stood there has been completely removed. A loop is provided for the engine to work round its train and this is the only section of double track along the whole six miles. The harbour itself is as pathetic as the derelict stations, with a profusion of sidings which could hold without difficulty 70 to 80 trucks. Thus the handful of trucks, rarely more than 15, lying in one or two of the sidings, serve only to remind of a past prosperity now not enjoyed. Small coastal steamers and barges carrying mostly grain and stone use the harbour, which suffers badly from the disadvantage of being tidal.” [19: p127]

It is worth commenting that Whitstable has seen a renaissance in the late 20th- and early 21st- centuries. It is a pleasant place to wander and has seen a real recovery in its economy.

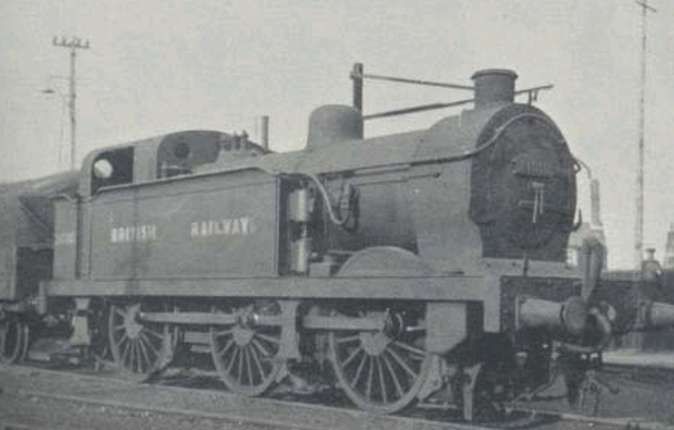

Crook continues his 1950s commentary: “There are now no signals along the track but the telegraph wires appear intact, though off their poles in some places. A modern touch is provided by standard Southern Railway cast-concrete gradient signs and mile posts. The latter give the route miles to London via Canterbury East and Ashford, and, as a point of interest, by this route London is [76.25] miles from Whitstable compared with 59 miles by the Victoria-Ramsgate main line. … Originally two goods trains each day were needed to keep abreast of the traffic, but now one is ample. It takes half-an-hour to arrive from Canterbury, there is an hour’s leisurely shunting in the harbour, and the return to Canterbury is made at about 1 p.m. There is no train on Sundays. Goods carried mostly are confined to coal into Whitstable and grain into Ashford. At one time coal from the Kent mines was exported from Whitstable, but now the coal which comes this way is entirely for local use and is not a product off the local coalfields alone, but mostly from the Midlands. In the other direction, grain is unloaded at Whitstable from class “R1” six-coupled freight tanks which are in accord with the historical traditions of the line, for no fewer than three Chief Mechanical Engineers have shared in producing the version seen today. Originally known as Class ‘R’, they were built between 1888 and 1898 by the South Eastern Railway and were among the last engines to appear from Ashford under the Stirling regime, 25 being built in all. On the formation of the S.E.C.R.. some of the class were modified by Wainwright and classified R1, a total of 23 ‘Rs’ and ‘R1s’ survived to be included in the Southern Railway stock list. Nine of these subsequently were further modified to enable them to work over the Canterbury & Whitstable line and succeeded some of Cudworth’s engines. At the end of 1950, all the ‘Rs’ and all but 10 of the ‘R1s’ had been scrapped. The surviving ‘R1s’ which can work this route are Nos. 31010, (now 61 years old). 31069, 31147, 31339, and these engines all make regular appearances.” [19: p127-128]

Because of the gradients on the line, working rules stipulated that trains had to be limited to 300 tons (18 loaded trucks) from Canterbury to Whitstable, and 200 tons in the other direction, but by the early 1950s loads rarely approached these figures. “Modifications were necessary to reduce the height of the ‘Rs’ and ‘Ris’ so that they could negotiate the tunnel on the branch, these alterations included the fitting of a short stove pipe chimney, a smaller dome, and pop safety valves. The ‘R1’ rostered for duty on the Canterbury and Whitstable line spends the rest of its day as yard pilot in the sidings at Canterbury West. It is coaled and watered there, and returns to Ashford only at weekends.” [19: p128]

The reduced headroom in the tunnel also meant that while most open type wooden and steel trucks were permitted over the route, no closed wagons were. “For the grain traffic, special 12-ton tarpaulin hopper wagons were used. These [had] fixed side flaps and [were] all inscribed with the legend ‘When empty return to Whitstable Harbour’. Special brake vans [were] used also. Because of weight restrictions, the ‘R1s'[were] not allowed over all the harbour sidings, and trucks there [were] horse drawn or man-handled.” [19: p128]

Crook concludes his article with some comments which were topical at the time of writing: “In recent years there has been strong agitation for the railway to be re-opened for passengers, but these efforts have been unsuccessful. It had been suggested that, as Canterbury is to be a local centre for the Festival of Britain, and the line has such an historical background, a passenger service should be reinstated for a trial period during the coming summer, but this was considered impracticable. … Perhaps specially-built diesel railcars would provide a satisfactory solution. On the other hand however strong the case for re-opening, it must be admitted that the need for special rolling stock constitutes a serious difficulty.” [19: p128]

“The line was in use for over 120 years. Passengers were carried until 1931 after which the line was used for goods only. The line finally closed on the 1st of December 1952, but was re-opened for several weeks in 1953 after the great floods cut the main coastal line on the 31st of January. The line was offered for sale in the late 1950s and large sections of the line were sold to private landowners. … The world’s oldest railway bridge in Whitstable was knocked down in 1971 to make way for cars. Thirty metres of the tunnel collapsed in 1974 and by 1997 the whole route was disused built on, or overgrown, almost entirely forgotten…” [17]

Two short notes about the Canterbury and Whitstable Railway:

A. A Canterbury and Whitstable Echo (The Railway Magazine, June 1959)

“Indignation has been expressed by residents in Whitstable at a recent substantial increase in the local rates, and the Urban District Council has been criticised for purchasing the harbour last year from the British Transport Com-mission for £12,500. This purchase accounts for 5d. of the 4s. 4d. increase in the rates. Whitstable Harbour was the first in the world to be owned by a railway company; it was among the works authorised by the Canterbury & Whitstable Act of incorporation of June 10, 1825. The railway was closed completely in December, 1952, and has been dismantled. In present circumstances, it probably is but cold comfort for the disgruntled residents to stress the historical interest of the harbour, quite apart from its commercial value. For them the fact remains that the purchase by the local authority of this adjunct to the pioneer railway in Kent has resulted in an increase in their rates.” [22]

B. Whitstable Harbour (The Railway Magazine, September 1959)

“Sir, Your editorial note in the June issue is of considerable interest to railway historians, for in addition to the fact that Whitstable Harbour was the first in the world to be owned by a railway company, it was also via this harbour that one of the earliest combined railway and steamboat bookings was introduced … In 1836, a local steam packet company agreed with the Canterbury & Whitstable Railway for the issue of tickets between Canterbury and London, and advertised that the ship William the Fourth, with Captain Thomas Minter, would leave Whitstable at 12 o’clock every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, and that the connecting train from Canterbury would leave that station at 11 o’clock. The journey from London would be made on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. The advertised single fares (including the railway journey) from Canterbury to London were in chief cabin 6s., children 4s.; and in fore cabin 5s., children 3s. 6d. The advertisement was headed with a small picture of the steam packet and the words, ‘Steam to London from Whitstable and Canterbury to Dyers Hall Steam Packet Wharf near London Bridge‘.” [23]

NB: There is at least a question mark to the assertion that Whitstable Harbour was the first in the world to be owned by a railway company. We know that Port Darlington was opened in December 1830. Whitstable harbour was built in 1832 to serve the Canterbury and Whitstable Railway which opened earlier. [24]

References

- C.R. Henry; The Canterbury and Whitstable Railway: The Second Public Railway Opened in England; in The Railway Magazine, London, October 1907, p305-313.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canterbury_and_Whitstable_Railway, accessed on 3rd November 2024.

- Samuel Lewis; ‘Whitley – Whittering’. A Topographical Dictionary of England; Institute of Historical Research, 1848

- https://waterways.org.uk/waterways/discover-the-waterways/kentish-stour, accessed on 8th November 2024.

- http://www.forgottenrelics.org/tunnels/haie-hill-tunnel, accessed on 8th November 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/102343570, accessed on 9th November 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.4&lat=51.28569&lon=1.07653&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th November 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.9&lat=51.29739&lon=1.07007&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th November 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.8&lat=51.30970&lon=1.06424&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th November 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.8&lat=51.32336&lon=1.04957&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th November 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.8&lat=51.34712&lon=1.04568&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th November 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.8&lat=51.35763&lon=1.03637&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th November 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.8&lat=51.36336&lon=1.02749&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 8th November 2024.

- The Kent Herald of 6th May 1830.

- https://railmaponline.com/UKIEMap.php, accessed on 23rd December 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whitstable_Harbour_railway_station, accessed on 24th December 2024.

- https://crabandwinkle.org/past, accessed on 25th December 2024.

- https://www.whitstable.co.uk/the-whitstable-crab-and-winkle-way, accessed on 27th December 2024.

- D. Crook; The Canterbury and Whitstable Railway in 1950; in The Railway Magazine, London, February 1951, p106-107 & 125-128.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Whitstable_Harbour_Railway_Station_001.jpg, accessed on 30th December 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2654059, accessed on 30th December 2024.

- Editorial; The Railway Magazine, London, June 1959, p370.

- Reginald B. Fellows; Letters to the Editor: Whitstable Harbour; in The Railway Magazine, London, September 1959, p649.

- https://www.canterbury.co.uk/whitstable-harbour/our-history, accessed on 25th August 2025.