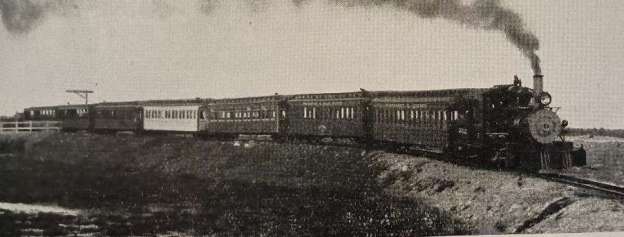

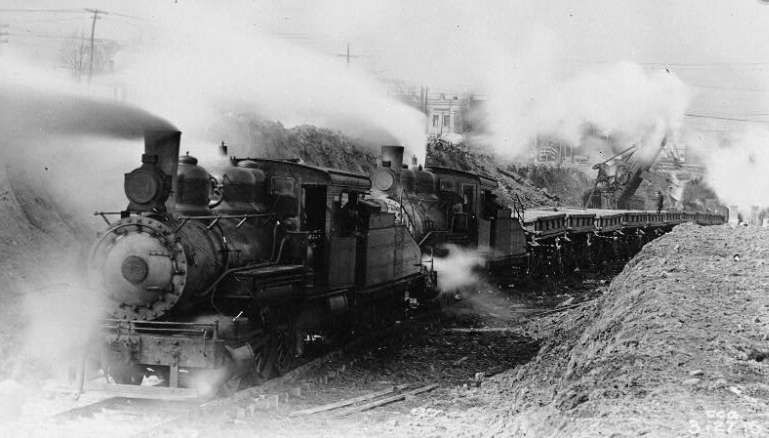

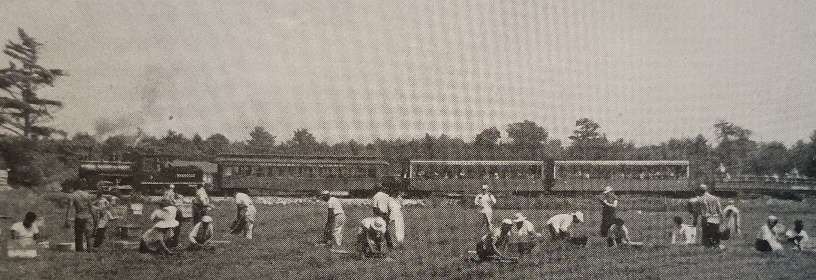

The featured image shows a passenger train on the Edaville Railroad, made up of coaches from other narrow gauge lines, running on a shallow embankment over a cranberry bog, © Public Domain. [1: p555]

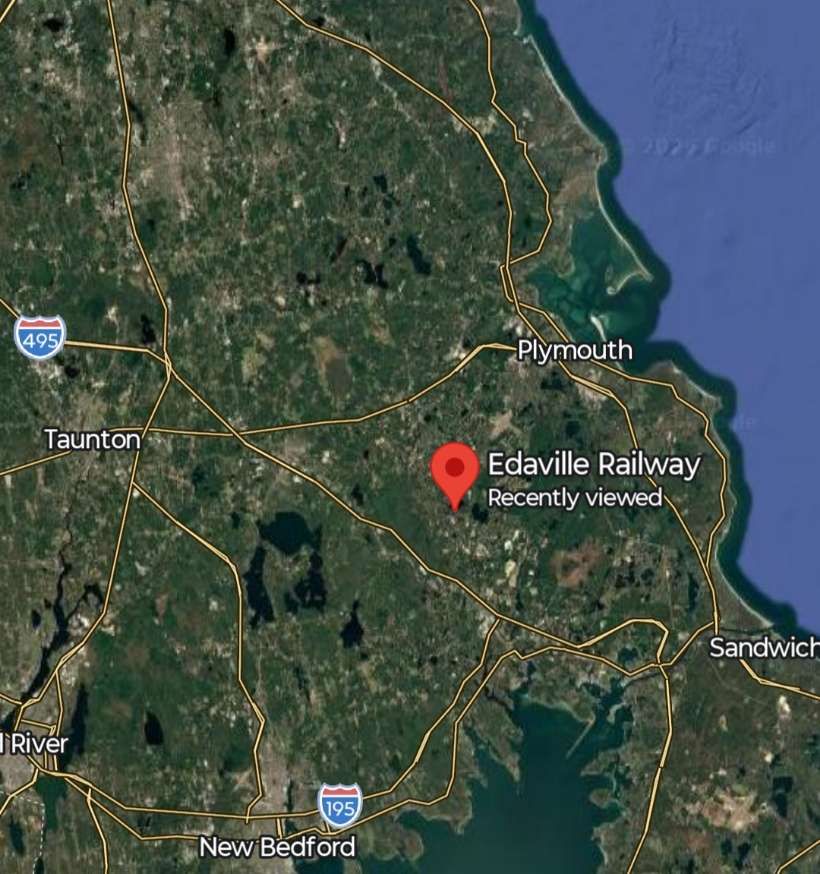

Originally known as ‘The Cranberry and Small Fry Line’, the Edaville Railroad is a 2ft-gauge narrow gauge line in Massachusetts. [1: p555]

It featured in a short article in the August 1952 issue of The Railway Magazine. This is the next article in a series looking at lines featured in early issues of The Railway Magazine.

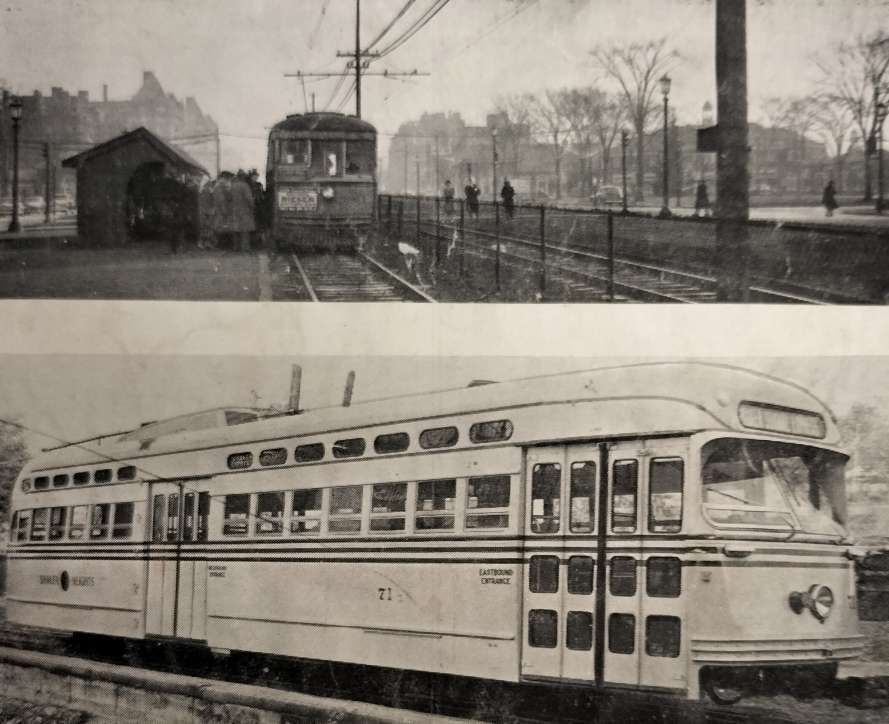

Writing in 1952, Edwards comments: “Although never exceptionally numerous, lines of this type assisted materially in the development of many areas. As early as 1877, a 2-ft. gauge line, eight miles long, was inaugurated to link the Massachusetts towns of Bedford and Billerica, but the track and plant were removed to the State of Maine two years later, and used for the Sandy River Railroad. This line proved of great service to many previously isolated communities; its development was rapid, and extensions and branches soon brought its mileage up to 120. Other similar projects followed, mostly in Maine, and a sixty-year period of success resulted. In recent years, however, the usefulness of such small lines has declined. The present economic situation has proved an adverse factor … and nearly all of them have been closed.” [1: p555]

He continues: “Nevertheless, one small American line – the Edaville Railroad, of South Carver, Massachusetts seems to have a long and useful life ahead of it. Not only is it a commercially paying proposition, but it performs a special function each Christmas, bringing delight to thousands of children (and their parents).” [1: p555]

The truth is that the line’s history has proven to be much more chequered than Edwards seemed to envisage in the early 1950s. But that is getting ahead of ourselves. There is plenty of space in the rest of this article to look at the later history of the line.

Returning to Edwards article, he says that the line “owes its existence to a plan of … Ellis D. Atwood, who was developing an area of bog as a cranberry plantation. … [By 1952], the Atwood plantations form[ed] the largest privately-owned cranberry plant in the world. A railway enthusiast himself, Mr. Atwood saw in a small-gauge railroad, not only a fulfilment of a life-long ambition to possess his own system, but the very necessary provision of transport for his workpeople and the materials used in his organisation. For instance, 10,000 cu. yd. of sand are used to preserve the bogs during winter, and the narrow-gauge railway solved this problem in a way that probably no other transport could have met, in view of the soft nature of the terrain. Then, of course, the line is fully occupied at harvest time conveying both the fruit and the pickers at a very low cost to its owners. The coaches are also used by the pickers as shelters during the inclement weather often experienced at harvest time; for this they are sited at convenient spots along the line during working hours.” [1: p555]

Edwards says that “In 1939, the 2-ft. gauge Bridgton & Saco River Railroad in Maine almost the last of the [2-ft.] narrow-gauge systems in the United States decided to dispose of its track and rolling stock. This was Atwood’s great opportunity. He bought the plant and rolling stock, and with the purchase of other equipment acquired by collectors from similar small lines passing out of business, the Edaville Railroad (so named by taking its founders initials) was commenced. This search for equipment, and systematic planning and correct siting, took some six years, but in 1946, the railway, complete with facilities for overhauling and repair of rolling stock, stations, auxiliary tracks, and points systems, came into full operation. The stock was four locomotives, eight coaches, six observation cars of the typical American pattern, a parlour car, and numerous trucks for everyday haulage work.” [1: p555-556]

“Thus it was as a utility-hobby that the Edaville Railroad grew. Originally there was no thought of catering for the public, but quite without any prompting from the owners, public interest was aroused.” [1: p556]

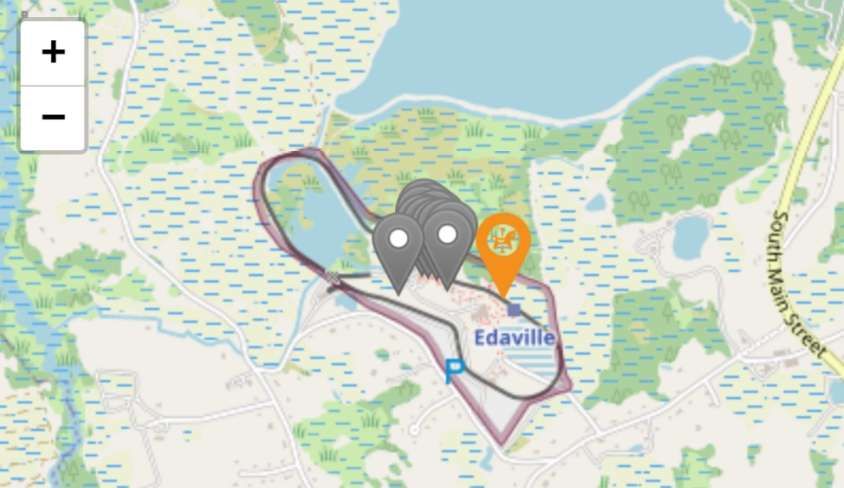

Wikipedia provides additional detail: “Atwood purchased two locomotives and most of the passenger and freight cars when the Bridgton and Saco River Railroad was dismantled in 1941. After World War II, he acquired two former Monson Railroad locomotives and some surviving cars from the defunct Sandy River and Rangeley Lakes Railroad in Maine. This equipment ran on 2 ft (610 mm) narrow gauge tracks, as opposed to the more common 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge in the western United States. Atwood purchased the equipment for use on his 1,800-acre (730 ha) cranberry farm in South Carver. After the 1945 cranberry harvest, Atwood’s employees built 5.5 mi (8.9 km) of track atop the levees around the cranberry bogs. Sand and supplies were hauled in to the bogs, and cranberries were transported to a “screen house” where they were dried and then sent to market. Atwood’s neighbours were enchanted with the diminutive railroad. At first, Atwood offered rides for free. When the demand for rides soared, he charged a nickel a ride. Eventually the line became less of a working railroad and more of a tourist attraction.” [2]

Edwards says that, “This interest became a clamour, and the Atwood Plantation Company built a station, and opened the line at weekends to passengers, from the spring of each year until harvest time. Throughout the summer, parties from schools, camps, church organisations, and youth groups arrive[d] at Edaville Station for a journey on the last 2-ft. gauge railway in America. While awaiting the trains they [could] visit a railway museum built by the company to house working models of American trains dating back to 1860, and many other interesting railroad relics.” [1: p556]

At Christmas, the Edaville Railroad really came into its own. After harvest, the railway would close until the first week in December when it reopened for what were quite spectacular Christmas excursions. …

Apparently, “12,000 coloured fairy lights [were] used to illuminate the various buildings on the estate, the 300-acre reservoir, the pine forests, and the cranberry bogs on the 5.5-mile journey.” [1: p556] This is all akin to the Santa Specials and the Polar Express experiences offer by many preservation line in the UK in the run up to Christmas.

As of 1952, Edwards says that these sightseeing rides in winter and summer cost young passengers nothing, although as many as a thousand five-cent tickets were sold as souvenirs each day. [1: p556]

Atwood died in 1950 after an industrial accident. “His widow Elthea and nephew Dave Eldridge carried on operations at Edaville until the railroad was purchased in 1957 by F. Nelson Blount, a railroad enthusiast who had made a fortune in the seafood processing business. The Atwood Estate retained ownership of the land over which the railroad operated, a key point in later years. Blount operated Edaville for the next decade, hauling tourists behind his favorite engine, No 8, and displaying his ever-growing collection of locomotives. Among these was the Boston and Maine Railroad’s Flying Yankee. This helped form the basis for his Steamtown, USA collection, first operating at Keene, New Hampshire, before moving to Bellows Falls, Vermont. (It would later move and be reconstituted as the Steamtown National Historic Site in Scranton, Pennsylvania.)” [2]

Blount was a distant relative of the Atwood family. [6]

Wikipedia continues: “Nelson Blount died in the crash of his light airplane over Labor Day weekend in 1967. Blount’s friend and right-hand man Fred Richardson continued on as general manager until the railroad was sold to George E. Bartholomew, a former Edaville employee, in 1970. … Edaville continued operations for another two decades with Bartholomew at the helm. The railroad operated tourist trains from Memorial Day [through to] Labor Day plus a brief, but spectacular, Festival of Lights in December. …. In the 1980s, Bartholomew’s attention was divided between the narrow gauge Edaville, and the 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge Bay Colony Railroad he was then forming, running over disused Conrail branch lines. To some observers and former employees, Edaville began to stagnate around this time, although the annual Christmas Festival of Lights continued to draw huge crowds.” [2]

“In the late 1980s, after Mrs. Atwood died and the Atwood Estate evicted Edaville, Bartholomew was forced to cease operations. He eventually put the railroad up for sale in 1991.” [2]

Wikipedia continues: “Edaville ceased operations in January 1992 and much of the equipment was sold to a group in Portland, Maine, led by businessman Phineas T. Sprague. The equipment was to be the basis of the newly formed Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad Museum along the shores of Casco Bay. The sale generated great rancor. Many of the railroad’s employees were not ready to give up on South Carver. Much of the contents of the museum, housed in the former screen house, had been auctioned off the previous fall. But the sale was closed (although the Portland museum took on a debt that would prove all but crushing in subsequent years) and locomotives 3,4 and 8 were trucked to Portland aboard antique trucks loaned for the occasion. Locomotive No. 7, which was owned by Louis Edmonds, left for Maine at a later date.” [2]

Two attempts to revive Edaville during the 1990s foundered. A third attempt in 1999 saw “the new Edaville Railroad opened for operation. Owned and operated by construction company owner Jack Flagg, developer John Delli Priscoli and cranberry grower Douglas Beaton, the railroad acquired a ‘new’ steam locomotive, No. 21 “Anne Elizabeth”, built by the English firm of Hudswell Clarke and a veteran of the Fiji sugar industry. Several of the original Edaville buildings, including the station and the engine house, were demolished with new buildings taking their place. Plans called for the construction of a roundhouse, served by the original turntable, with an enlarged collection of locomotives and rolling stock.” [2]

“By 2005, Edaville Railroad and the land upon which it ran was now owned by a single man, Jon Delli Priscoli. He bought up the Atwood property, bought out partner Jack Flagg, and became the sole owner. Although this removed the railroad/landlord conflict that had plagued Edaville for decades, it proved to be the end of the “old” Edaville. Delli Priscoli turned the land near the milepost known as “Mt. Urann” into a housing subdivision, and pulled up the tracks that ran through the new lots. Late 2005 saw the very last run over the “original line” (pulled by oil-burner No. 21, which had been cosmetically modified to more closely resemble a Maine prototype). When the rails were removed over Mt. Urann, the mainline became a 2-mile (3.2 km) loop, including about half of the line around the old reservoir.” [2]

Wikipedia continues: “In late 2010, the Edaville operators announced that they would not seek to renew their operating lease with Delli Priscoli. Delli Priscoli then put the railroad up for sale for $10 million, and eventually found a potential buyer. However, Priscolli found that the buyer did not intend to continue operating the park, and declined the offer, opting instead to rebuild the park. The restored railroad reopened in September 2011. The following year, the park began a three-year reconstruction project, which includes the installation of additional attractions, refurbishing and repainting existing rides, adding additional parking, and building a new main street entrance and guest services area.” [2]

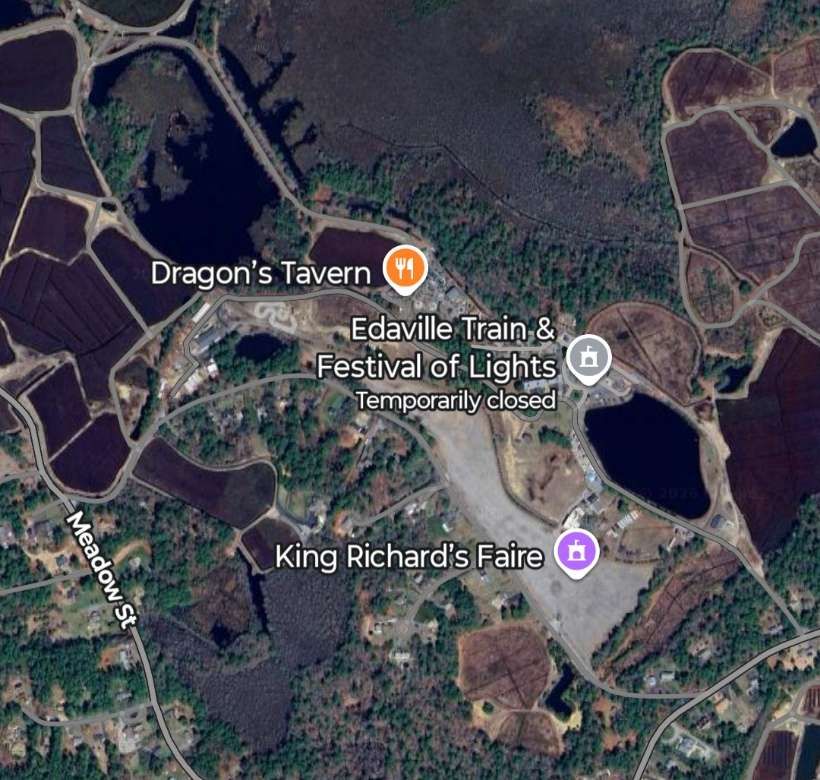

In the years under Priscoli, Edaville Railroad reopened as Edaville Family Theme Park, an amusement park themed around cranberry harvesting and railroading.

Wikipedia continues: “As of 13th April 2022, Delli Priscoli put Edaville back on the market. The family amusement park [had] closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, and except for the return of the annual Christmas Festival of Lights … has remain closed.” [2]

As of 2025, various options were being explored for re-opening as a more traditional, historic railway attraction. [2] As of January 2026, details of the Christmas Festival of Lights in 2025 can be found here. [6] The then site owners said that “Classic traditions and trains will remain for Edaville’s Christmas Festival of Lights, while a reimagining of the space allows future generations to get to know the joy of Edaville. Long time fans, train enthusiasts, and newcomers can plan to see steam locomotives on trains as much as possible, giving a rare experience as the only operating steam locomotives in Massachusetts!” [7][8]

It remains to be seen whether this attraction survives the next few years and what form it will take. The site was taken over by King Richard ‘s Faire in 2025. [9]

References

- Austin Edwards; The Cranberry and Small Fry Line; in The Railway Magazine Volume 98 No. 616; Tothill Press,h London, August 1952, p555-556.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edaville_Railroad, accessed on 27th January 2026.

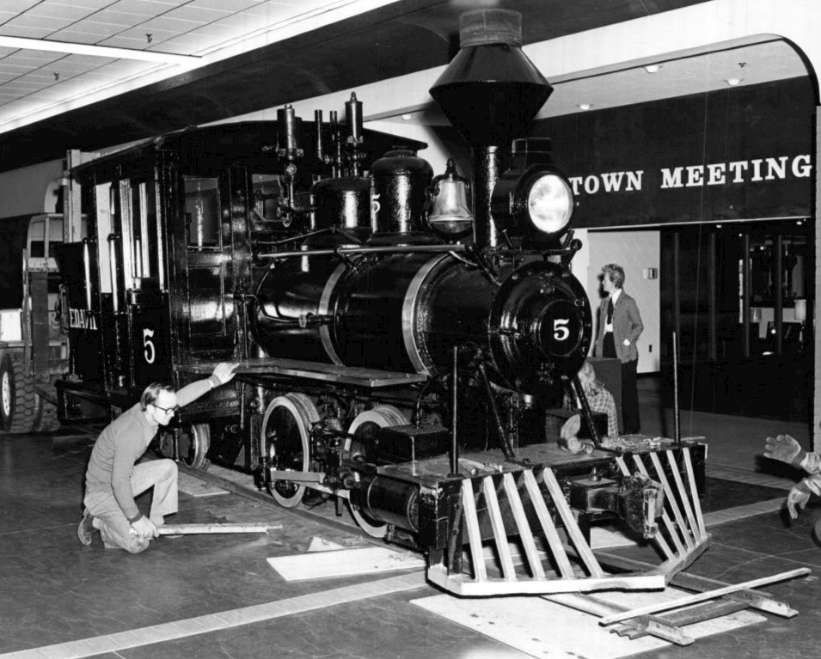

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edaville_Railroad_Engine_No._5_at_Burlington_Mall_1973.JPG, accessed on 27th January 2026.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1FzD1iUv6t, accessed on 27th January 2026.

- https://www.railarchive.net/randomsteam/edav8.htm, accessed on 27th January 2026.

- https://www.edaville.com, accessed on 28th January 2026.

- https://coasterpedia.net/wiki/Edaville_Family_Theme_Park, accessed on 28th January 2026.

- https://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/Attraction_Review-g41490-d285087-Reviews-Edaville_Holiday_Festival_of_Lights-Carver_Massachusetts.html#/media-atf/285087/?albumid=-160&type=0&category=-160, accessed on 28th January 2026.

- https://www.kingrichardsfaire.net, accessed on 28th January 2026.