Earlier articles in this short series about steam railmotors can be found on these links:

The Earliest Steam Railmotors:

Steam Railmotors – Part 1 – Early Examples.

Dugald Drummond and Harry Wainwright:

Steam Railmotors – Part 2 – Dugald Drummond (LSWR) and Harry Wainwright (SECR)

The GWR Steam Railmotors:

Steam Railmotors – Part 3 – The Great Western Railway (GWR)

Rigid-bodied Railmotors of Different Companies in the first two decades of the 20th century:

Steam Railmotors – Part 4 – Rigid-bodied Railmotors owned by other railway companies

Articulated Steam Railmotors in the First 2 decades of the 20th Century

Jenkinson and Lane comment that although the articulated railmotors were numerically less significant than the rigid type, “the articulated option was to sprout just as many variations, and attracted the attention of a number of eminent locomotive engineers – perhaps because they looked more like ‘real’ trains. Be that as it may, most of them, however short-lived or unsustainable they may have been, were of more than usually pleasant visual aspect.” [1: p26]

Examples of articulated railmotors were those of the Taff Vale Railway (TVR), the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway (L&YR) the South Eastern & Chatham Railway (SECR), the North British Railway (NBR), the London Brighton & South Coast Railway (LB&SCR), the North Staffordshire Railway (NSR), the Rhymney Railway (RR), the Port Talbot Railway (PTR), the Isle of Wight Central Railway (IWCR), the Glasgow and South Western Railway (G&SWR), and the Great North of Scotland Railway (GNSR).

We have already picked up on the decisions made by Harry Wainwright of the SECR. Others were making the same decisions at roughly the same time. …

The Taff Vale Railway Railmotors

Tom Hurry Riches (1846–1911) “became the Locomotive Superintendent of the Taff Vale Railway in October 1873, and held the post until his death on 4 September 1911. At the time of his appointment, he was the youngest locomotive superintendent in Britain.” [5]

His steam railmotors “were built between 1903 and 1905, … one prototype and three main batches. There were 18 engine units and 16 carriage potions, … permitting stand-by power units to be available. … The pioneer power unit came from the company’s workshops (the last ‘locomotive’ to be built by the TVR in its shops at West Yard, Cardiff) followed by six each from Avonside and Kerr Stuart and a final five from Manning Wardle, the last type being much more powerful than the first three series, which were broadly identical.” [1: p21]

The first-class compartment of Riches prototype was “furnished with longitudinal seats. The third-class compartment [was] furnished with transverse seats arranged in pairs, divided by a central gang-way. The car underframe [was] constructed of steel, and … carried at one end on an ordinary carriage bogie, the wheels of which [were] Kitson’s patent wood cushioned type; the other end of the car [was] carried on the engine.” [7]

All of the TVR Steam Railmotors had transverse boilers and were driven from rearward-placed cylinders onto an uncoupled front axle. [7]

The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Steam Railmotors

The Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (L&YR) operated two classes of twenty steam railmotors in total. [10]

Kerr Stuart Railmotors

Kerr, Stuart & Co. built 4 Steam Railmotors for the L&YR (2) and the TVR (2) as a single batch in 1905. [10]

“The locomotive units had transverse boilers … where a single central firebox fed extremely short fire-tubes to a smokebox at each side. … These then returned to a central smokebox and chimney. The outside cylinders were rear-mounted and drove only the leading axle, without coupling rods. The locomotive units were dispatched separately to Newton Heath, where their semi-trailers were attached.” [10][11: p170-171]

Their coaches were semi-trailers, with reversible seats for 48 passengers and electric lighting. There were also a luggage compartment and a driving compartment for use in reverse. Folding steps were provided at each of the two doors on each side. [11: p155] They were built by Bristol Wagon & Carriage Works. [11: p170-171]

Hughes Steam Railmotors

George Hughes (9 October 1865 – 27 October 1945) was … chief mechanical engineer (CME) of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (L&YR) and the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS). [13].

When the L&YR amalgamated into the LNWR in January 1922 he became the CME of the combined group and was appointed the CME of the LMS on its formation at the 1923 grouping. [13][14]

He retired in July 1925 after only two and a half years at the LMS. [11: p198] He was succeeded by Henry Fowler who had worked with him at Horwich Works before moving to the former Midland Railway’s Derby Works. [15: p38]

Hughes designed a second class of railmotors that were then built at Horwich and Newton Heath, in four batches over five years. They were of the “0-4-0T locomotive + semi-trailer type”, with conventional locomotive boilers. [11: p155, 170-171] In total, 18 power units were made to Hughes specification.

“All were inherited by the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) in 1923, who numbered the locomotives 10600-17 and gave the trailers separate numbers in the coaching stock series. These were the only self-propelled vehicles numbered in the LMS locomotive series rather than the coaching stock series. The first was withdrawn in 1927, and only one survived by nationalisation in 1948. That railmotor, LMS No. 10617, was withdrawn in 1948 and given the British Railways internal number 50617, but got withdrawn in March of the same year. None were preserved.” [10][16]

The best-remembered of these railmotors was the ‘Altcar Bob’ service from Southport to Barton railway station (also known as ‘Downholland’) (before 1926, it ran to Altcar and Hillhouse) and the ‘Horwich Jerk’ service from Horwich to Blackrod. The latter became the last part of the L&Y System which made use of Hughes Railmotors.[10][16]

Many of the last survivors of these 18 Railmotors ended their lives at Bolton MPD and in their final hours were used on the workmen’s’ trains between that town and the works at Horwich. [17]

South Eastern & Chatham Railway (SECR) Steam Railmotors

These were covered in the 2nd article in this short series:

Steam Railmotors – Part 2 – Dugald Drummond (LSWR) and Harry Wainwright (SECR)

Jenkinson and Lane comment that the SECR was surprisingly a leader in the field. “Harry Wainwright supervised the design of eight beautifully stylish examples in 1904-5.” [1: p26]

Despite determined efforts over the years to improve their efficiency, the Railmotors were non-too-popular and were scheduled for withdrawal in 1914. The war intervened and gave a longer life to some units, but soon after the war they were all set aside, although some survived unused into the grouping era.

Great Northern Railway (GNR) Steam Railmotors

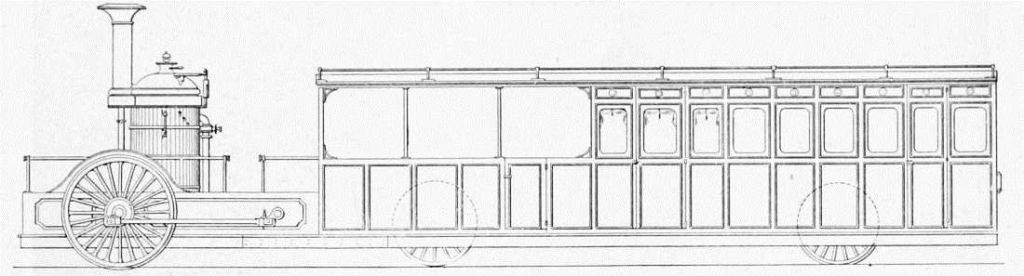

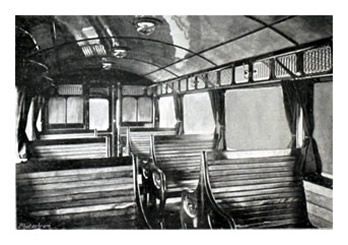

Ivatt, on behalf of the GNR, had six railmotors built in pairs, with similar passenger accommodation but differing in other details. He had them produced “as part of a GNR experiment with self-propelled passenger units and numbered in a new series 1&2, 5&6, 7&8, the missing 3&4 being kept for two proposed petrol engined cars of which … only one was bought.” [1: p28] All six units utilised the underfloor area of the carriage portion to house the water tanks. [1: p28]

Nos. 1&2 were built by the GNR themselvescat Doncaster in 1905, the passenger portions were among the earliest passenger ‘coaches’ to be given full elliptical roofs. “In 1930, the passenger ends were converted to an articulated twin (Nos. 44151-2) but only lasted until 1937 because of damage received in a mishap at Hatfield.” [1: p27]

Nos. 5&6 were built by Kitson and Co. in 1905. The locomotive portion was of very similar design to Nos 1&2. Their passenger bodies were supplied by Birmingham Carriage and Wagon Works. They had the traditional flatter roofs which tied in with the profile of the roof of the engine portions. [1: p28]

Nos. 7&8 were built by Avonside with carriage bodies from Bristol Carriage and Wagon Works. The Avonside locomotive portion was rather bulky (Jenkinson and Lane describe it as ‘brutish’ [1: p28]) and was soon remodelled because maintenance was hampered by an engine casing which cloaked most of the fitments. The passenger portions of these units were converted to another pair of articulated carriages (Nos. 44141-2) which survived until they were condemned in 1958. They “worked the Essendine- Bourne branch until 1951 and afterwards in such widespread like captions as Mablethorpe, Newcastle-Hawick and finally Bridlington-Scarborough.” [1: p28]

These railmotors lasted in service until 1917 when they were set aside. After the grouping, the LNER saw little use for the units and as noted above “the carriage parts were converted into articulated ‘twins’ … And the engine portions [were] withdrawn. ” [1: p28]

Steam Railmotors on the London Brighton & South Coast Railway (LB&SCR)

Jenkinson and Lane say that the LB&SCR and the North Staffordshire (see below) articulated steam railmotors had much in common, both being built by Beyer Peacock in 1905-6.[1: p30][21: p62] “They displayed a sort of cross-bred powered end, partially enclosed but with smokebox front and chimney projecting in a rather quaint fashion beyond the ‘cab’ – probably very practical for cleaning purposes. The engine portions were identical on both railways but the carriage portions displayed different styling – those of the Brighton line being rather neater. Fortunately, … both types were reasonably well recorded photographically, especially those of the NSR.” [1: p30]

The LB&SCR examples did not seem to be well received and only lasted for a few years, albeit not being formally withdrawn for some time. [1: p30]

Both companies’ railmotors, by comparison with other articulated railmotors, were rather ungainly looking with a sort of tramcar-like passenger part. [1:p30]

The pair of steam railmotors “were stationed at Eastbourne and St Leonards and ran services on the East and West Sussex coast lines. They were both loaned to the War Department in 1918/19 before being sold to the Trinidad Government Railway. [21: p67] There they have never been put in operation. One of the coach parts was converted into the Governor’s saloon and the other into a second class carriage.” [2][22]

North Staffordshire Railway Steam Railmotors (NSR)

As we have already noted, the three [1:p9][23] steam railmotors owned by the NSR were built by Beyer Peacock in 1905-6. Jenkinson and Lane comment that, given their longer active lives, (the three NSR examples ran until 1922), “they must have generated a bit of revenue during the 16 years or so before they went the way of the rest.” [1: p30]

Rhymney Railway (RR) Steam Railmotors

After Tom Hurry Riches moved to the Rhymney Railway he had Hudswell Clarke build a pair of railmotors for the RR. They consisted of an 0-4-0 engine portion semi-permanently articuled with a 64-passenger coach. T. Hurry Riches designed the combination, contracting with Cravens Ltd of Sheffield to build the passenger coaches. All seating was designed for third class and was divided between smoking and non-smoking sections. [27]

In 1911, RR No. 1 “was converted to an independent, mixed-traffic tank locomotive that operated chiefly between Rhymney Bridge, Ystrad Mynach, and Merthyr with four six-wheel coaches. At that time, No. 2 still ran on the Senghenydd branch.” [27]

Port Talbot Railway and Docks Co. (PT&DR) Steam Railmotor

Port Talbot Railway and Docks Company (PT&DR) owned a single rigid-bodied steam railmotor, numbered No.1. The GWR persuaded the PTR&DR to purchase it. Tenders were submitted by 15 companies “and a joint tender from Hurst, Nelson & Co. Ltd and R. & W. Hawthorn, Leslie and Company was accepted and the vehicle was delivered in early 1907. This was the largest steam railmotor ever to run in the UK. it was 76 ft 10 in (23.42 m) long, and the bodywork was metal, that covering the engine fashioned to match the carriage. Retractable steps were fitted under each of the four recessed passenger doors, although the steps were later fixed in position.” [28][29]

Hawthorn Leslie built two steam railmotors for use in Great Britain, and at least one for abroad. [30]

“The locomotive was six-coupled with 3 ft diameter wheels; it had a conventional boiler with the firebox leading, 12 by 16 inch cylinders and a boiler pressure of 170 psi and a tractive effort of 9,792 lbs.” It was designed with a trailing load in mind. [28]

It was the only Steam Railmotor in the UK to have a six-coupled power section. [1: p9]

This Railmotor passed through GWR hands to the Port of London Authority (PLA). In 1915, the GWR moved it to their Swindon works then in 1920 it became PLA No.3. It remained in service until the North Greenwich branch of the PLA closed and was scrapped in 1928. [28]

Isle of Wight Central Railway (IWCR) Steam Railmotor

The Isle of Wight Central Railway had a single Railmotor which was built in 1906 by R.W. Hawthorn (engine) and Hurst, Nelson & Co. of Motherwell (carriage). Jenkinson and Lane tell us that this railmotor was delivered in-steam from Hurst, Nelson & Co. works to Southampton Docks.

Once on the island, the railmotor took up duties on “the Merstone to Ventnor Town service, and then transferred to the Freshwater line in 1908. Although highly regarded in terms of economy, … it was … prone to oscillation and … ‘laid aside’ in November 1910.” [1: p34]

Once the railmotor was placed out of service, the two parts of the railmotor were repurposed. The carriage entered the regular coaching stock of the railway (with an added bogie). The engine “was given a small bunker and was used at Newport for occasional shunting, before being sold in 1918.” [1: p34] It was sold to Furness Shipbuilding, Haverton Hill and became their No. 8.

Glasgow & South Western Railway (G&SWR) Steam Railmotors

The G&SWR had three steam railmotors on its books which lasted in service until 1917. Two to one design and the third to a slightly different design.

No. 1 and No. 2 were built at Kilmarnock in 1904. The ‘side tanks’ were used to carry coal with water carried in a 500 gallon well tank. These units were used on the Catrine branch shuttle to Mauchline and from Ardrossan to Largs and Kilwinning. [1: p34-5]

The only image that I have found of Railmotors No. 1 and No. 2 is a copyright protected thumbnail image. It can be seen by clicking here. [34]

No. 3 was not strictly a steam railmotor as the engine and carriage were close-coupled rather than articulated. Jenkinson and Lane winder whether it should be included within the scope of a book about railmotors but decide to include it because “it was designed as an integrated concept … Intended for the Moniaive branch on which one of the G&SWR railmotors certainly ran.” [1: p35]

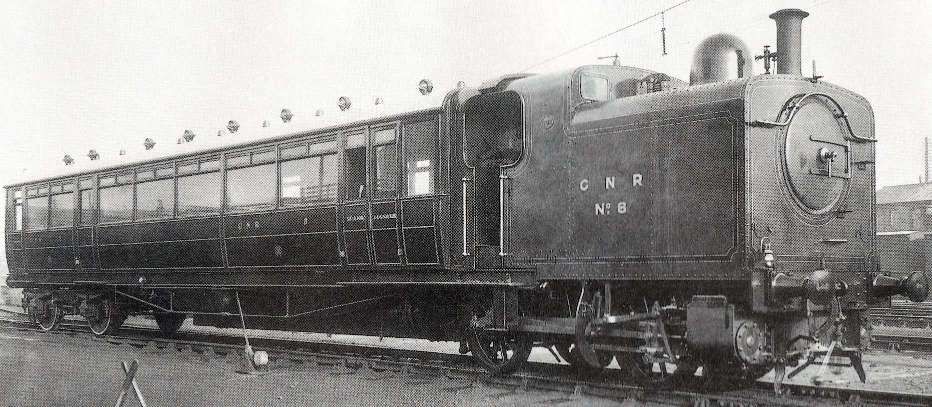

Great Northern of Scotland Railway (GNSR) Steam Railmotors

The two GNSR railmotors had some unique design features – patented boilers and hemispherical fireboxes. They were, however, not a success and they were withdrawn after just a few years. [1: p34]

The two articulated units were designed by Pickersgill and built by Andrew Barclay & Co. of Kilmarnock and powered by vertical boilers made by Cochran & Co. of Annan. They entered service on the Lossiemouth and St. Combs branches in 1905. [35]

The boilers were new to locomotive work but of a type well-known in other fields. 10 in. x 16 in. cylinders were placed just ahead of the rear bogie wheels and drove on to the leading axle. Walschearts valve gear was used. The 4 wheels of the power unit were 3 ft. 7in. diameter. [35]

A small bunker attached to the front of the coach body formed the back of the cab and held 15 cwt. of coal. Underneath the leading end of the coach there was a 650-gallon water tank.

The coach portion of the rail motor consisted of a long passenger compartment and a small compartment at the rear end, with doors for ingress and egress of passengers, also serving as a driving compartment when the unit was being driven from that end. The passenger compartment was 34 ft. 7in. long and seated 45 while the overall length of the car was 49 ft. 11 ½ in. and the total weight 47 tons. [35]

“The two engine units were numbered 29 and 31, (Barclay’s numbers 1056-7). The coaches were Nos. 28 and 29. Unit 29/28 went to work on the St Combs Light Railway on 1st November 1905, and 31/29 started working on the Lossiemouth branch on the same day.” [35]

The two units were not a success and “in the course of time the engine units were detached from the coaches and used as stationary boilers. Here they were apparently more successful; on the line they were dreadfully noisy and the boilers would not steam properly, and the hopes of their designer were not realized.” [35]

References

- David Jenkinson & Barry C. Lane; British Railcars: 1900-1950; Pendragon Partnership and Atlantic Transport Publishers, Penryn, Cornwall, 1996.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_steam_railcars, accessed on 14th June 2024.

- R.M. Tufnell; The British Railcar: AEC to HST; David and Charles, 1984.

- R.W. Rush; British Steam Railcars; Oakwood Press, 1970.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tom_Hurry_Riches, accessed on 19th June 2024.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taff_Vale_railmotor_(Rankin_Kennedy,_Modern_Engines,_Vol_V).jpg, accessed on 19th June 2024.

- http://www.penarth-dock.org.uk/09_04_090_02.html, accessed on 19th June 2024.

- The Taff Vale Railmotor, in the Railway Magazine, February 1904; via http://www.penarth-dock.org.uk/09_04_090_02.html, accessed on 19th June 2024.

- National Museum and Galleries of Wales – Amgueddfa Cymru — National Museum Wales – archive; included in Mountfield & Spinks; The Taff Vale Lines to Penarth; The Oakwood Press; via http://www.penarth-dock.org.uk/09_04_090_02.html, accessed on 19th June 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%26YR_railmotors, accessed on 19th June 2024.

- John Marshall; The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway. Vol. 3: Locomotives and Rolling Stock; David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1972.

- https://www.railforums.co.uk/threads/lancashire-and-yorkshire-hughes-rail-motors-running-backwards.222458, accessed on 19th June 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Hughes_(engineer),accessed on 19th June 2024.

- George Hughes; in Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History. Archived from the original on 20th June 2017 and retrieved 22nd August 2019, accessed via https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Hughes_(engineer),accessed on 19th June 2024.

- Patrick Whitehouse & David St. John Thomas; LMS 150; David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1987.

- G. Suggitt; Lost Railways of Lancashire; Countryside Books, Newbury, 2003.

- https://wp.me/pwsVe-R1, accessed on 19th June 2024

- https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/275193815724?mkcid=16&mkevt=1&mkrid=711-127632-2357-0&ssspo=yXJFhbJMSuC&sssrc=4429486&ssuid=afQhrar7TGK&var=&widget_ver=artemis&media=COPY; accessed on 19th June 2024.

- https://www.southeasternandchathamrailway.org.uk/gallery.html, accessed on 19th June 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/ferroviastrens1/photos/a.162504877245931/2159328897563509/?type=3&mibextid=rS40aB7S9Ucbxw6v, accessed on 19th June 2024.

- D.L. Bradley; Locomotives of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway. Part III.; Railway Correspondence and Travel Society Press, London, 1974.

- Locomotives of the Trinidad Government Rlys; in Locomotive Magazine and Railway Carriage and Wagon Review, Vol. 42 No. 522, 15th February 1936, p53–55. Archived from the original on 28th January 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023, accessed via https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_steam_railcars, on 20th June 2024.

- https://www.nsrsg.org.uk/chronology.php#NSR, accessed on 20th June 2024.

- https://redrosecollections.lancashire.gov.uk/view-item?i=214678&WINID=1718865502724, accessed on 20th June 2024.

- https://www.lner.info/locos/Railcar/gnr_railmotor.php, accessed on 20th June 2024.

- https://x.com/SleeperAgent01/status/1280269864175894529?t=FyeWO8DJP5xUPrL5hnbaqg&s=19, 20th June 2024.

- https://www.steamlocomotive.com/locobase.php?country=Great_Britain&wheel=0-4-0&railroad=rhymney, accessed on 20th June 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_Talbot_Railway_and_Docks_Company, accessed on 18th June 2024.

- Robin G Simmonds, A History of the Port Talbot Railway & Docks Company and the South Wales Mineral Railway Company, Volume 1: 1853 – 1907, Lightmoor Press, Lydney, 2012

- http://www.britishtransporttreasures.com/product/r-w-hawthorn-leslie-co-ltd-catalogue-section-steam-rail-motor-coaches, accessed on 18th June 2024.

- https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/File:Im1963EnV216-p221.jpg, accessed on 18th June 2024.

- https://x.com/DamEdwardurBoob/status/1051567390251597824?t=q01zKvK-GVPLXT7ilVlYaA&s=19, accessed on 20th June 2024.

- https://pin.it/35Lh0CRNz, accessed on 20th June 2024.

- https://www.mediastorehouse.com.au/mary-evans-prints-online/glasgow-motor-carriage-603697.html, accessed on 20th June 2024.

- https://steamindex.com/locotype/gnsr.htm#:~:text=Steam%20rail%20motors%2Frailcars%20(Pickersgill%2FAndrew%20Barclay)&text=These%20units%20consisted%20of%20a,on%20an%20ordinary%20coach%20bogie., accessed on 20th June 2024.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GNSR_steam_railmotor_(Railway_Magazine,_100,_October_1905).jpg, accessed on 20th June 2024.