The featured image at the head of this article shows BR No. 54445 with an permanent way train passing Culloden Moor Viaduct travelling towards Aviemore. [54]

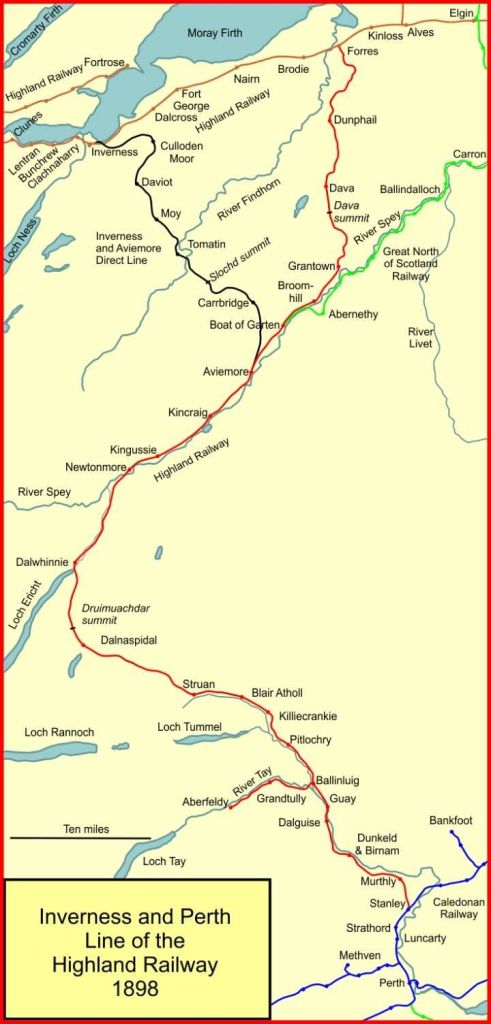

The Inverness and Aviemore Direct Railway was built by the Highland Railway to provide a shorter and more direct route between Inverness and Aviemore, carrying its main line traffic to Perth and the south.

Earlier articles about the Highland Railway can be found here, [7] here, [8] here, [9] here, [10] and here. [11]

The original route via Forres and Dava, built by the Inverness & Perth Junction Railway (I&PJR), “ran over wild and remote terrain as far as Aviemore, and then on to Dunkeld. From there trains used the Perth and Dunkeld Railway to Stanley Junction, and from there the Scottish North Eastern Railway to Perth. This was a considerable improvement [over the only previously available route via Aberdeen], although operation of the line over the mountainous route was difficult. The traffic from east of Forres proved to be lighter than anticipated, and at the same time traffic from Inverness and from the Inverness and Ross-shire Railway became increasingly dominant. The deviation to Forres before turning south was now a serious liability.” [1]

It was also clear that the Great North of Scotland Railway (GNSR) was planning its own independent line between Elgin and Inverness and the West Highland Railway was known to be considering a line along the Great Glen connecting from Fort William to Inverness. “The Highland Railway was alarmed at both of these competitive encroachments into what it considered to be its own territory. It anticipated that Parliament would look favourably on them, if it could be shown that the Highland Railway was not taking adequate steps to improve its own line and its service to passengers and goods customers.” [1][2: p44][3: p103-104]

“The solution was a new line of 34 miles running directly south from Inverness, rejoining the existing Perth line at Aviemore. This became the Inverness and Aviemore Direct Railway, informally known as the Carr Bridge line, or later the Carrbridge line. Its authorising Act of Parliament was passed on 28th July 1884.” [1][3: p104][4: p175]

As Acworth noted in 1890, the Highland Railway “could never face a Parliamentary Committee and maintain that the existing facilities to Inverness were sufficient, when it had taken no steps to supply the additional accommodation whose necessity it had itself asserted only a few years before … The construction of the new road will mean to [the Highland Railway], in the first place, a capital expenditure of some hundreds of thousands of pounds; secondly the cost of working some thirty additional miles; thirdly no additional traffic whatever; and lastly, the reduction of the passenger fares by as many pence as the new road will be shorter in miles than the old.” [1][5:p74-75]

“Having received the authorisation, the Highland Railway did nothing to hasten actual construction, no doubt believing that the danger of encroachment had been staved off. In any event, for the Highland Railway this was the most important development of the decade. … The cut-off was 34 1⁄2 miles of new line between Aviemore and Inverness. For six years from obtaining the necessary Act on 28 July 1884, the company managed to stave off any real action, although by 1886 agreements about land acquisition were made with proprietors. Altogether four extensions of time to complete the line were granted: two before and two during construction.” [1][2: p44][3: p103-104]

The Inverness to Aviemore Direct Railway was opened in stages: the first, from Aviemore to Carr Bridge, opened on 8th July 1892 as a branch line operated by a tank engine, and carrying very little traffic. [1][3: p103-104] The line from Carr Bridge to Daviot opened on 19th July 1897.

The route was completed for through running by the opening between Daviot and Millburn Junction, Inverness, on 1st November 1898. [1] Ot should be noted that there is some ambiguity over the dates. [1: Note 1]

In October 1897, it was decided to install double track on the as-yet unopened section between Inverness and Daviot. This involved widening some completed single-track bridges. [1][2: p8]

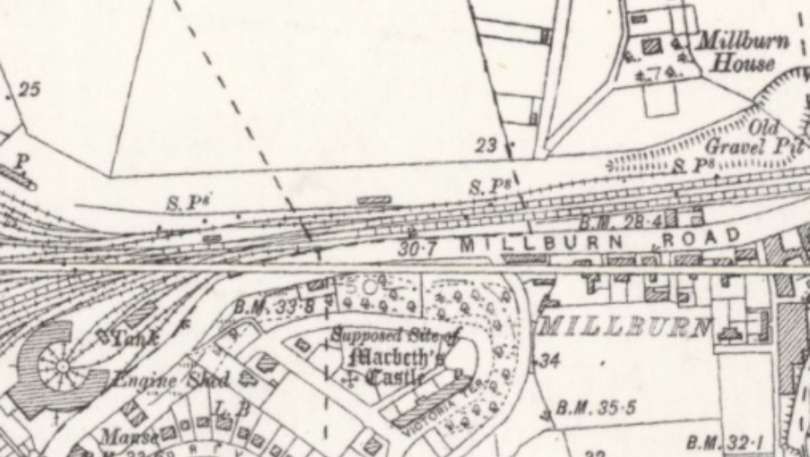

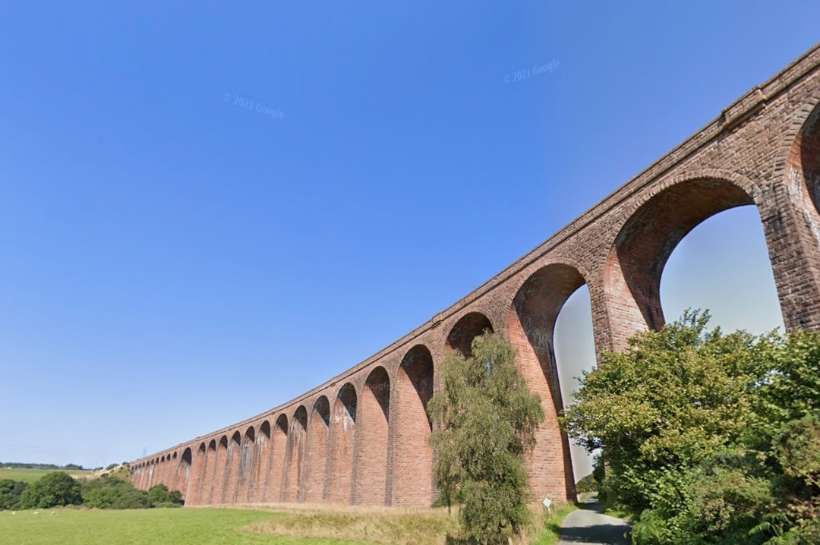

“The new line incorporated the Highland Railway’s second-highest summit: Slochd at 1,315 feet. The Strathnairn Viaduct near Culloden Moor is Scotland’s longest masonry viaduct at 600 yards in length; there are 29 arches. [1][3: p133-134][4: p197] Major enlargement of the track facilities was also carried out at Millburn Junction in Inverness. The total cost of the line was almost a million pounds.” [1][2: p46]

From the opening of the direct line from Aviemore… “the traffic planners had to cater for two main lines into Inverness from the south. In the summer of 1909, seven scheduled trains ran each day between Perth and Inverness. The night train from Perth left at 12.50 a.m., with sleeping car from Glasgow, and travelled via Carrbridge, arriving at 5.10 a.m. A connecting train left Aviemore for Forres at 4.00 a.m., arriving also at 5.10 a.m. Nairn passengers went on to Inverness and changed trains there. At 5 a.m. another train left Perth, conveying sleeping cars from London and through carriages from southern railways, running via Carrbridge and arriving at Inverness at 8.35 a.m. This ran only from 1 July to 11 August. Fifteen minutes later the ‘normal’ night train from London left Perth, and arrived in Inverness at 9.08 a.m. This train was also noted as conveying Sleeping Carriages Euston to Strathpeffer.” [3: p184-185]

“A Forres connection left Aviemore at 8.25 a.m., arriving at 9.35 a.m. The Mail left Perth at 6.15 a.m. and reached Aviemore at 8.33 a.m. Here it divided, the direct Inverness portion arriving at 10.10 a.m., and the Grantown portion arriving in Inverness at 11.15 a.m. A Saturdays-only train left Perth at 9.25 a.m., reaching Inverness at 1.50 p.m.; its Forres connection left Aviemore at 12.45, arriving 1.56 p.m. A train for Inverness via Forres still left Perth at 11.50 a.m., running non-stop to Newtonmore, which it reached at 1.44 p.m.; Forres was reached at 3.25, and Inverness at 4.15. Only ten minutes later, the old Parliamentary left Perth, stopping at all stations (five on request only) and reaching Inverness via Carrbridge at 4:36 p.m.” [3: p185]

The Route

Inverness Railway Station was covered in the first article in this series. [7]

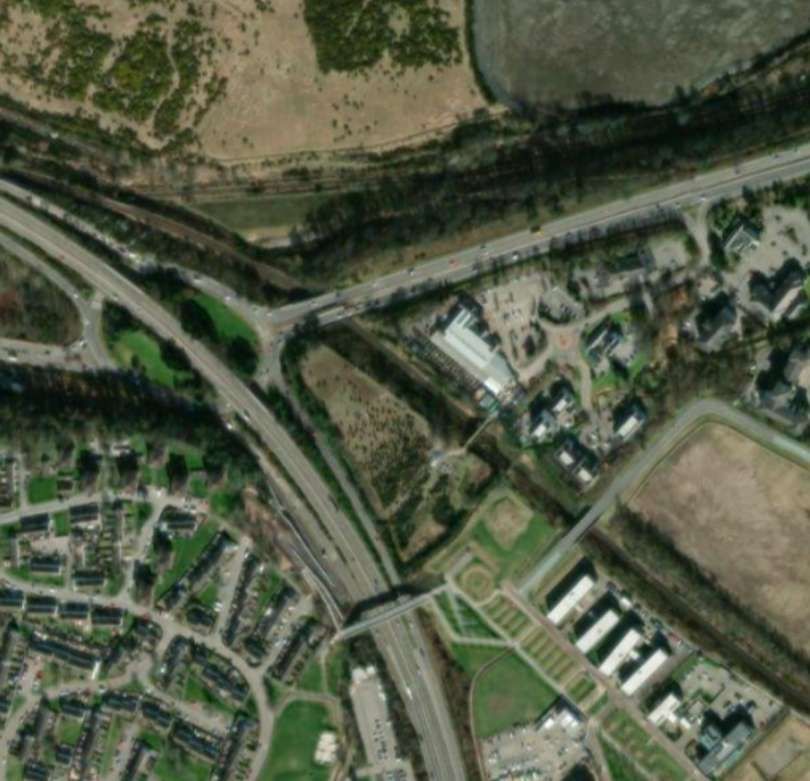

The Inverness to Aviemore Direct Railway curves round to the Southeast.

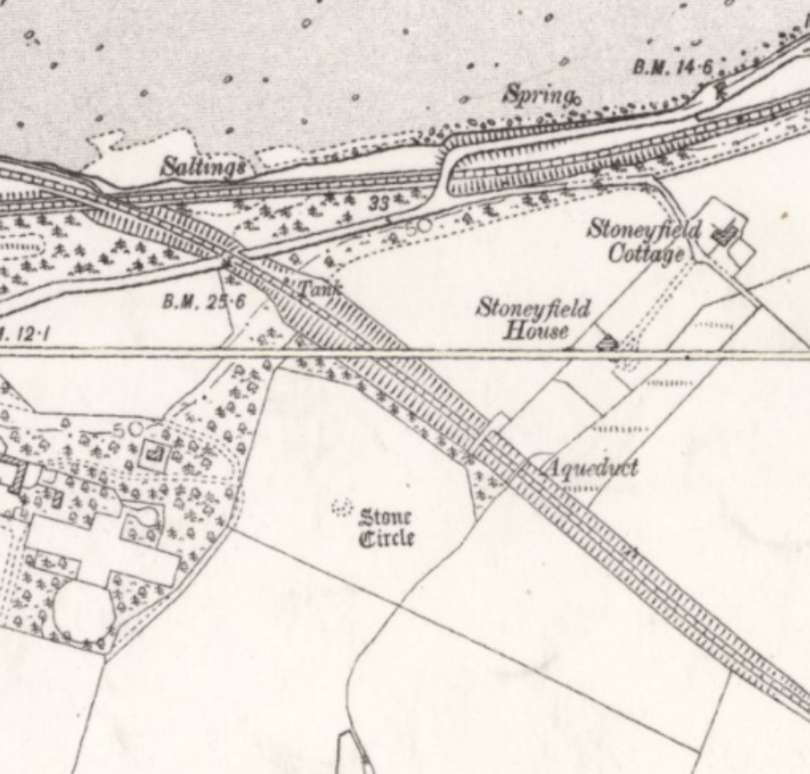

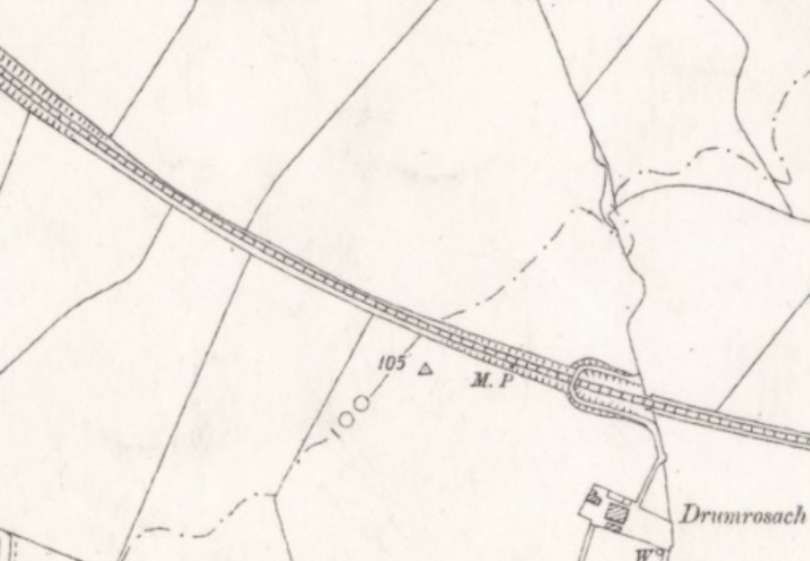

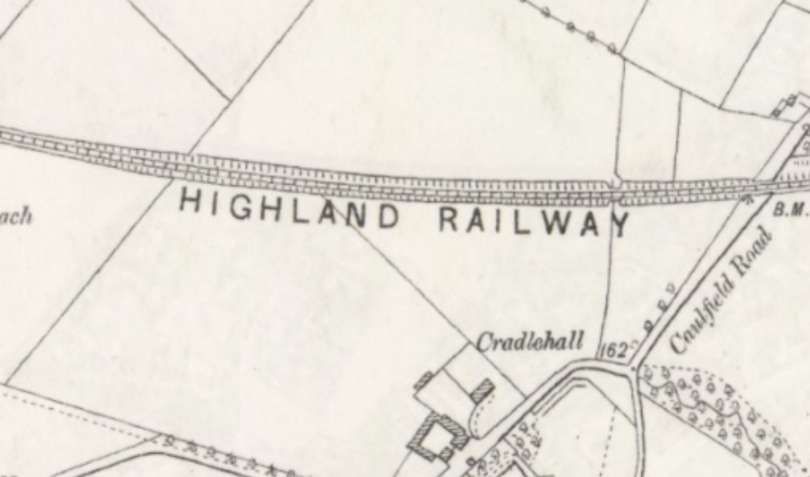

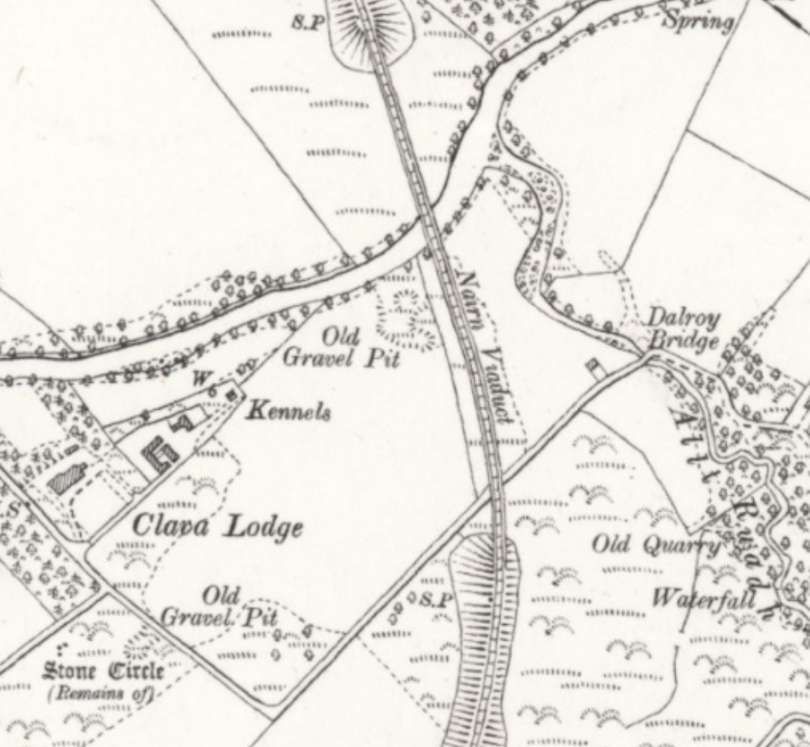

The line begins a wide curve round to the South to cross Culloden Moor. The line is initially in cutting, then on embankment and then in cutting on its approach to the site of Culloden Moor Railway Station.

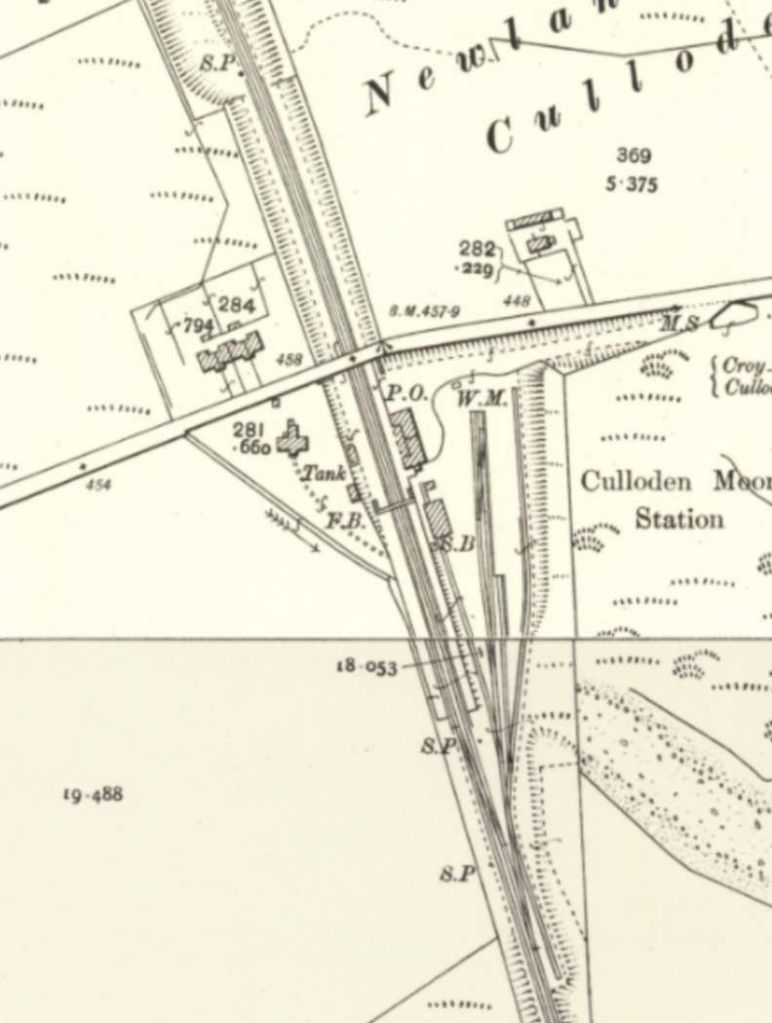

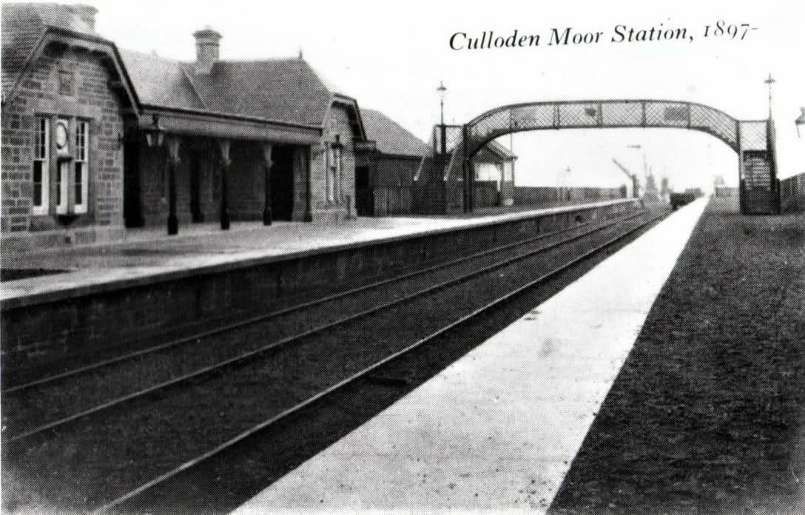

Culloden Moor railway station served the village of Culloden from 1898 to 1965 (1967 for general goods). It was a two platform station just to the north of the Nairn Viaduct. Its location was closed too to the site of the Battle of Culloden. The platforms remain but the station buildings have gone.

Both platforms at the station had a water column, with the water tank on the northbound platform. There was a bitumen depot adjacent to the station and in later years the goods sidings at the station could be seen filled with bitumen tank wagons. The depot closed towards the end of the 20th century. [22]

The camera is facing Southeast, towards Aviemore. The station was closed 3rd May 1965 (and to goods on 27th February 1967). The tank-wagons and sidings belonged to Highland Bitumen of Ardrossan, © Ben Brooksbank and licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-SA 2.0). [20]

Another photograph of the station can be seen here. [25] South facing photographs of Culloden Moor Railway Station have the Culloden Viaduct appearing in the distance.

The viaduct was designed by Chief Engineer Murdoch Paterson and built by The Highland Railway. Twentynine arches carry the line over the valley of the River Nairn. It opened in 1889 and it remains the longest masonry viaduct in Scotland at 1800ft (549m) long and is a Category A listed building. [27}

South of the viaduct the railway head for a short distance to the Southwest before turning Southeast as it arrives at Daviot Railway Station.

En-route the line crosses a minor road and

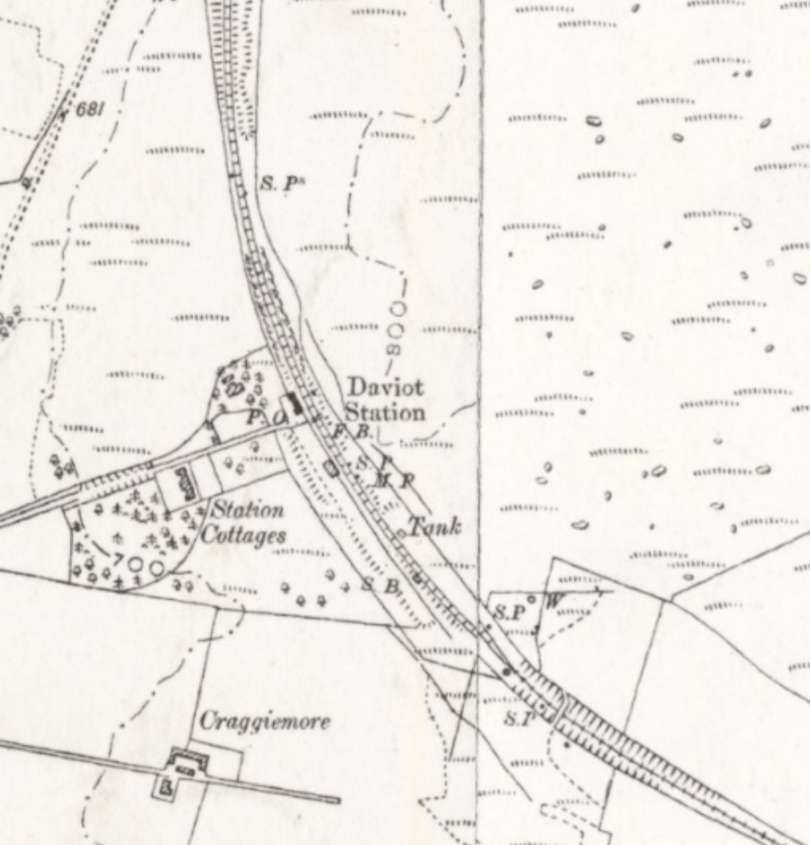

Daviot Railway Station opened on 19th July 1897.Ot was, for a short time the Northern terminus of the line from Aviemore until Culloden Moor Railway Station opened in 1898. Wikipedia tells us that, “on the northbound platform was the station building and to the southwest was the goods yard. There were two signal boxes: one to the north which was built, but never opened. The other signal box was to the south in between the goods sidings. It was relocated slightly to the north in 1952. The station closed on 3rd May 1965. The signal box closed in 1969. Only the platforms remain.” [29]

Ernie’s Railway Archive has an excellent photograph of the station which can be viewed here. [30]

Wikipedia tells that Moy Railway Station opened on 19th July 1897. “The station building was situated on the southbound platform. Goods facilities were handled at the northeast. There were two signal boxes: north and east. Despite their names, they were both situated to the west. The station closed to both passengers and goods traffic on 3rd May 1965.” [32] The station building at Moy was of a very similar design to that at Culloden Moor and Daloit.

AmBaile has a monochrome image of the station at Moy. This image can be seen here. [34]

The modern A9 crosses the line of the railway to the East of Moy. The next two images are taken from the A9 road bridge.

Further Southeast we teach Tomatin Railway Station. …

AmBaile has a few photographs of Tomatin station. These can be seen here, [35] here, [36] and here. [37]

Findhorn Viaduct is around 500 metres East of Tomatin village. …

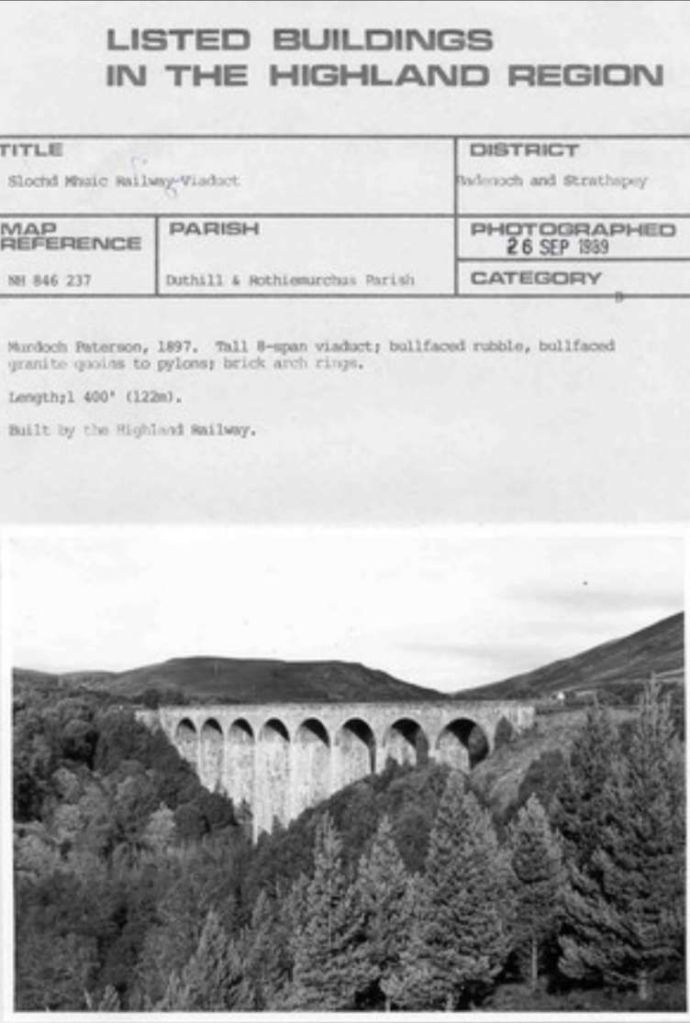

“The Findhorn Viaduct was designed and built for the Highland Railway between 1894 and 1897 by Murdoch Paterson, their chief engineer, and John Fowler, who was the consulting engineer and who also worked on the design of the Forth Rail Bridge. The viaduct was Fowler’s suggestion in order to create a more direct route; the railway company had originally planned a more circuitous route around the valley, over a mile longer. The steel for the lattice work was supplied by the Butterley Iron Company in Derbyshire, England. The granite for the piers was supplied by Kemnay Quarry in Kemnay, Aberdeenshire, which also supplied materials for the Forth Bridge. … It was opened to traffic on 19 July 1897. The viaduct is a Category B listed building, first listed in 1971, a status which grants it legal protection.” [39]

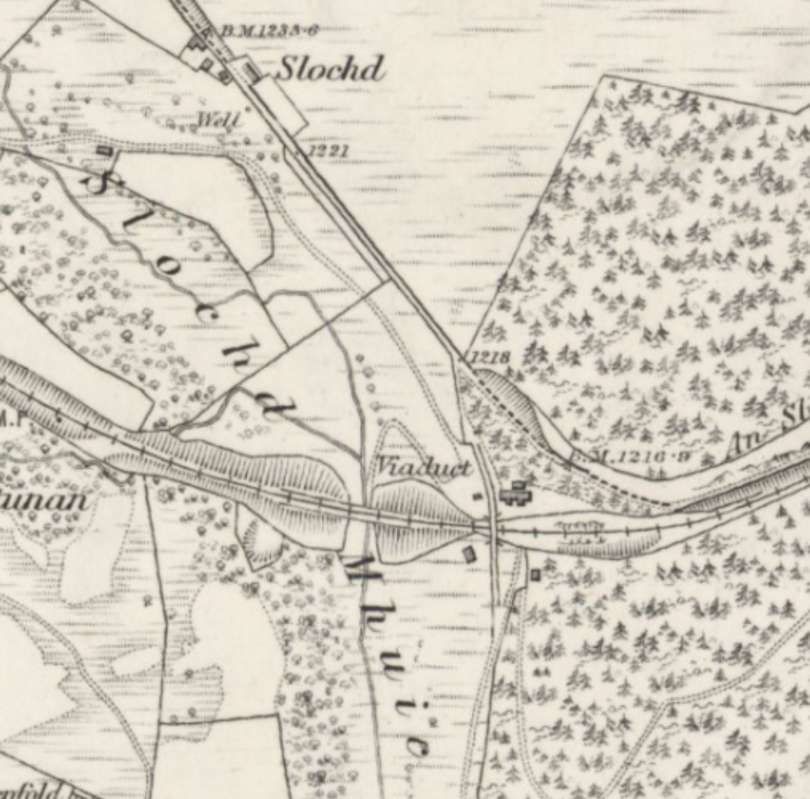

The highest point on the line between Inverness and Aviemore is at Slochd. The Slochd Summit “is a mountain pass on the A9 road and the Highland Main Line Railway. It is the highest point on the line between Inverness and Aviemore. An old military road and National Cycle Network Route No. 7 also go over the summit, the latter largely following the old A9. … Both the road and the railway have signs marking the spot – the A9 is at a height of 1,328 feet (405 m), while the railway reaches 1,315 feet (401 m). The Slochd Summit is the second highest place on the route from Inverness to Perth – the Pass of Drumochter at 1,500 feet (460 m) is higher and bleaker.” [41]

A very short distance to the East of Slochd, the old A9 (now National Cycle Route No. 7 crosses the old railway. …

East of the old A9 the railway curves round from a Northeasterly direction to a Southeasterly one. It runs down the valley of the Bogbain Burn crossing the stream a number of times on its descent. The modern A9 runs a little to the South of the railway. The Bogbain Burn joins the Allt nan Ceatharnuch and flows to the North of the railway before crossing under both the railway and the modern A9. It then flows into the River Dulnan to the West of the A9 and the railway.

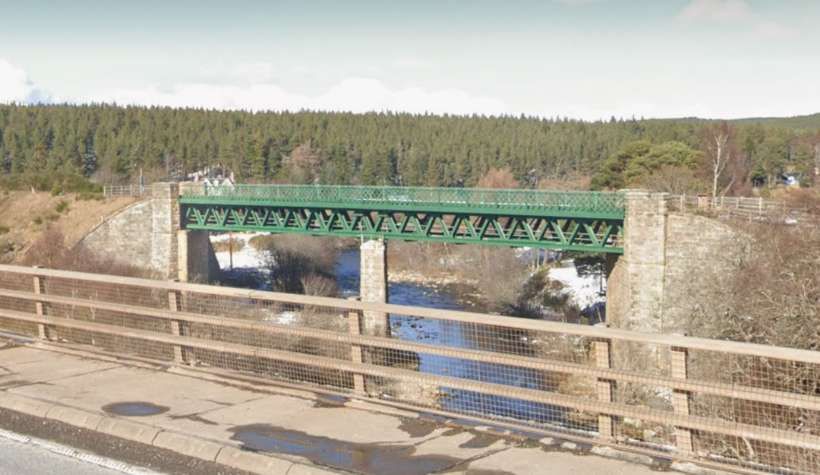

The River Dulnan flows under the A9 and the railway and then flows down through Carrbridge. The railway station sits about 1.5 km Southwest of the village close to the river. It remains open in the 21st century.

An historical photograph of the railway bridge over the river can be seen here. [53]

Carrbridge Railway Station was opened on 8th July 1892 when the Highland Railway opened the line from Aviemore. For five years Carrbridge was the terminus of the line from Aviemore.

Northbound services commenced on 8th July 1897 when the line to Daviot was opened, the line through to Inverness opened on 1st November 1898. … The station was built with a passing loop on the otherwise single track railway, a signal box (automatic token-exchange apparatus was used) and several sidings on the north side of the line. The station building is thought to be by the architect William Roberts, dating from 1898. A camping coach was positioned here by the Scottish Region from 1954 to 1965. [46]

Some photographs of steam at Carrbridge Station can be seen on the Carrbridge Past & Present Facebook Group. [51]

Southeast of Carrbridge Railway Station, the line curves through a heavily wooded landscape towards the South. It continues to be closely followed by the modern A9.

The A9 begins to turn away from the railway to the South of Kinveachy. The A95 passes under the railway as it heads South, along the route of the old A9.. A new skew bridge carries the railway over the road in the 21st century.

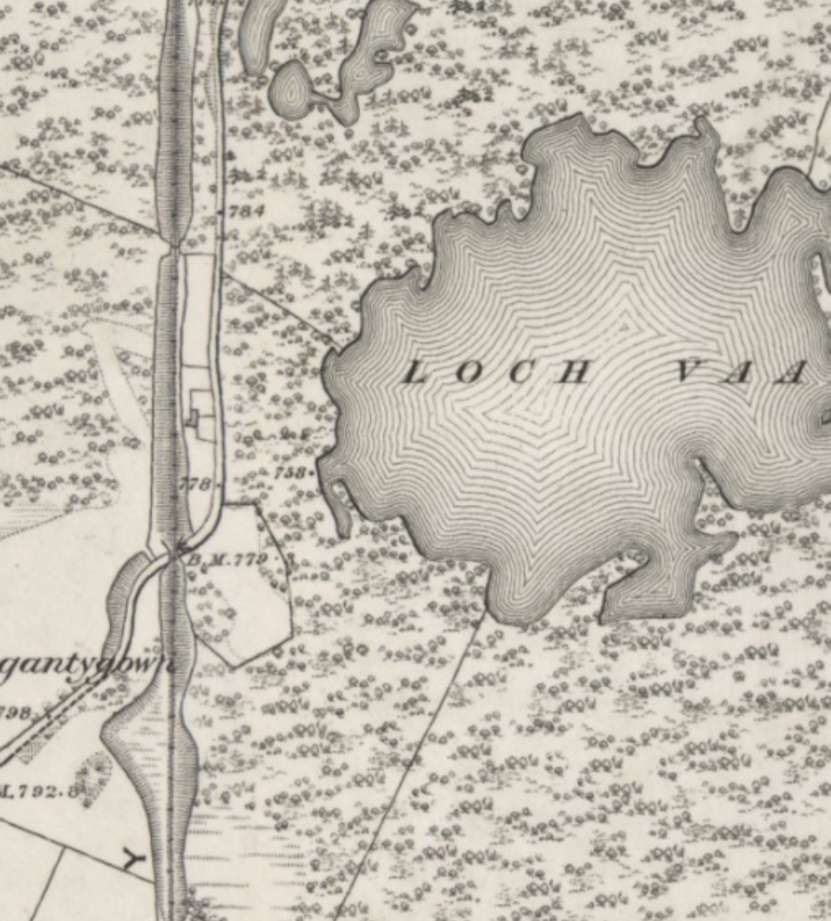

The railway heads due South towards Aviemore, before drifting towards the West … Three small lochans were in the path of the railway. …

In the 21st century the journey between Inverness and Aviemore takes less than 45 minutes. The older main line through Forres was abandoned as part of the cuts which followed the Beeching Report in the mid-1960s. As we noted when looking at the route via Forres and Dava, a preservation railway is active at the southern end of that line and shares Aviemore Railway Station with ScotRail. The line is followed by walkers and cyclists on The Dava Way. [50]

An article about the Gorres/Dava route can be found here. [8]

References

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inverness_and_Aviemore_Direct_Railway, accessed on 28th June 2025.

- Neil T Sinclair; The Highland Main Line; Atlantic Publishers, Penryn, 1998.

- David Ross, The Highland Railway, Tempus Publishing Limited, Stroud, 2005.

- H. A. Vallance; The Highland Railway (2nd. Ed.); David & Charles, Dawlish, and Macdonald, London, 1963, (First edition published in 1938).

- W M Acworth; The Railways of Scotland: Their Present Position, with a Glance at their Past and a Forecast of Their Future; John Murray, London, 1890.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2504196, accessed on 28th June 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/05/01/the-highland-railway-part-1/

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/06/28/the-highland-railway-part-2/

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/03/23/the-highland-railways-strathpeffer-branch/

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/04/01/the-highland-railways-fortrose-or-black-isle-branch/

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/05/03/the-highland-railways-fort-george-branch/

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=57.48184&lon=-4.22119&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 28th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=57.48289&lon=-4.21033&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 29th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=57.48347&lon=-4.19911&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 29th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=57.47913&lon=-4.17733&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 29th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=5l7.47702&lon=-4.16526&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 29th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=57.47693&lon=-4.15517&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 29th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=57.48195&lon=-4.18791&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 29th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=57.48344&lon=-4.06605&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 29th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3345327, accessed on 28th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3092339, accessed on 28th June 2025.

- https://www.railscot.co.uk/locations/C/Culloden_Moor, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.8&lat=57.48473&lon=-4.06669&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/16RLR3Py59, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/27041, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=57.47810&lon=-4.06291&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://www.visitinvernesslochness.com/listings/culloden-viaduct, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=57.43252&lon=-4.10570&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daviot_railway_station, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/irishswissernie/27794831248, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=57.38462&lon=-4.05668&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moy_railway_station, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=57.34370&lon=-4.00545&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 30th June 2025

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/27752, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/28019, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/28013, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/28005, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.0&lat=57.33467&lon=-3.98418&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, 30th June 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Findhorn_Viaduct_(Tomatin), accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5358534, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slochd_Summit, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=57.29157&lon=-3.91728&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://www.google.com/search?client=ms-android-motorola-rvo3&sca_esv=bec2fea0dbf0b6aa&sxsrf=AE3TifOz4h8t7Z-vFtcwUUMXFezZeqPmNA:1751311886771&udm=2&fbs=AIIjpHyqq7TquKTaG7yVdtxZ2GNmhBe0Q_JZIxG_Tc7OaN4aXNPzFKPxIlJ3AYkZGNOifgdX-pEQNjXSgwJdeelzvugdImdw-Ia9Fci-vfRQ8DKySVJapl_-feH6aEqb7iLzeTILZh2bE6PfvxY8STgqPz4flnlZrmT9VVZuhkeuCPhfvy5RNeVx1c1FJwQ2_R1wSuHfqJiycwMM2xDAGJ1JxGCkz5mlTLw9v42z3Fs-1GTLsp33I8A&q=allt+slochd+mhuic+viaduct&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiSp5uX8ZmOAxX2ZkEAHXD6NwoQtKgLegQIDBAB&biw=508&bih=970&dpr=2.13#sv=CAMSgwUa4wQKlQIKuQEStgEKd0FMa3RfdkhPdHJWZEFIQkFLalFaT3c3X1FiMmJ4ekZOTndNNnBkbllpdzk0WnE1TmtQeXFCdnZncVlCQy1US2FvSGp0SkVQdXlicFVIbWJYNjMzd1Q2ZVdFR3VQc0ZKQXI5Q1Blcy15RUZMSVY3OTU3YmktdlhvEhdGdVppYU5IRUd2M05oYklQaEk2dXFBTRoiQUZNQUdHcUhmdmhjR1NZZHI4aVNzM1RicHg3czlDYUtwdxIDODQ5GgEzIh4KAXESGWFsbHQgc2xvY2hkIG1odWljIHZpYWR1Y3QiBwoDdGJzEgAiJgoEZXFsZBIeQ2dJSUFCQUFPZ1FJQUJBQVZSLU9NRDl0eEF2QlBnErYCCs8BEswBCowBQUxrdF92R2Q1cXkydTRtQUxsQmd0YlNlVzVEd2tablZFaDVOZ3hENk8xTklCQkVxNUt2aHlZbHJvZGdhTGhZandubmIzX3ZXSDNWUV9sTUUtT3RzckZTV1dlejdIOUFzXzd5SVhrSldJUG5hemYtcEJZaGxzS0R0cHBNTnQ3dkJHSV85VTdZbDZFeVcSF0Z1WmlhTkhFR3YzTmhiSVBoSTZ1cUFNGiJBRk1BR0dxRlhtSlc4eEd5QU1hZWYyZjh1cXVmMjVyNlZBEgQ0Njk4GgEzIhgKBmltZ2RpaRIOQk1WVFFZMEFTa2lSek0iFwoFZG9jaWQSDm5jOHFWb0pOVXVObU5NIiYKBGVxbGQSHkNnSUlBQkFBT2dRSUFCQUFWUi1PTUQ5dHhBdkJQZyoQZS1CTVZUUVkwQVNraVJ6TSAEKhcKAXMSEGUtQk1WVFFZMEFTa2lSek0YATABGAcglfr0zAUwAUAC, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.2&lat=57.28230&lon=-3.82902&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 30th June 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carrbridge_railway_station,_looking_towards_Inverness.JPG, accessed on 1st July 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carrbridge_railway_station, accessed on 1st July 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.8&lat=57.23529&lon=-3.80389&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=96, accessed on 1st July 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.1&lat=57.21831&lon=-3.81059&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 1st July 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=57.19099&lon=-3.82734&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 1st July 2025.

- https://davaway.org.uk, June 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/16WHRJWHYz, accessed on 1st July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1FjShBjSET, accessed on 1st July 2025.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/27008, accessed on 1st July 2025.

- https://www.highlifehighland.com/highland-archive-centre/doors-open-day-saturday-1st-september-11-4/br-steam-locomotive-54445-with-up-permanent-way-train-passing-culloden-moor-viaduct, accessed on 1st July 2025.

- https://crlocomotives.livejournal.com/2566.html, accessed on 1st July 2025.