The December 1905 Railway Magazine focussed on Shrewsbury Railway Station as the 34th location In its Notable Railway Stations series. [1]

The featured image above is not from 1905, rather it shows the station in 1962. [14]

Lawrence begins his article about the relatively newly refurbished Shrewsbury Railway Station by remarking on the debt Shrewsbury Station owes to the construction of the Severn Tunnel: “it is to the Severn Tunnel that Shrewsbury owes the position it claims as one of the most important distributing centres in the country if not the most. In telephonic language, it is a “switch board,” and those on the spot claim that more traffic is interchanged and redistributed at Shrewsbury than even at York.” [1: p461]

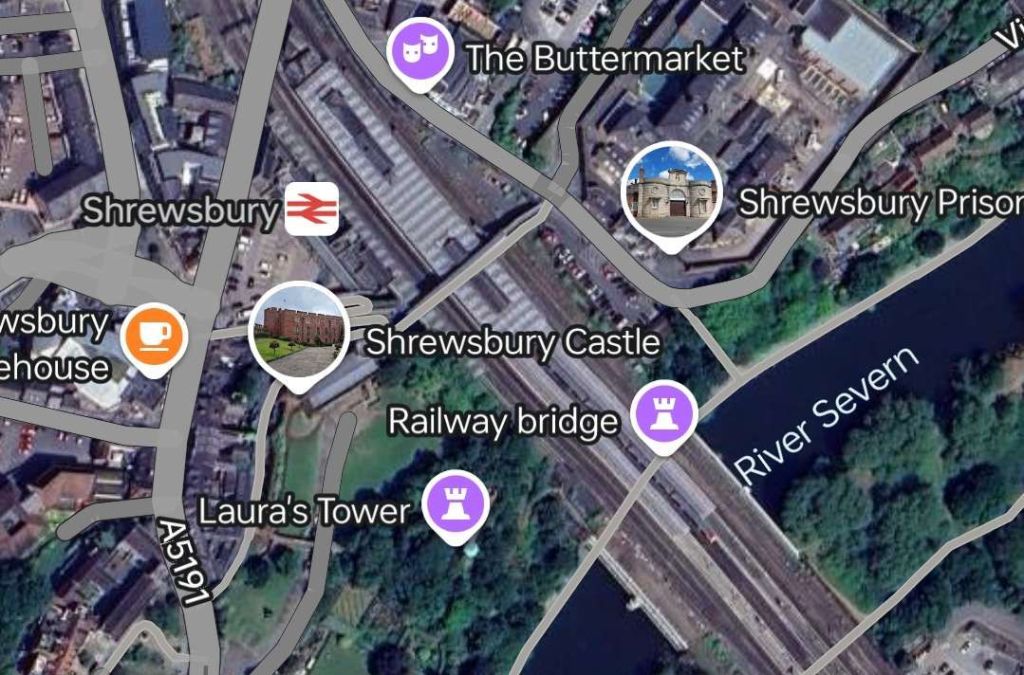

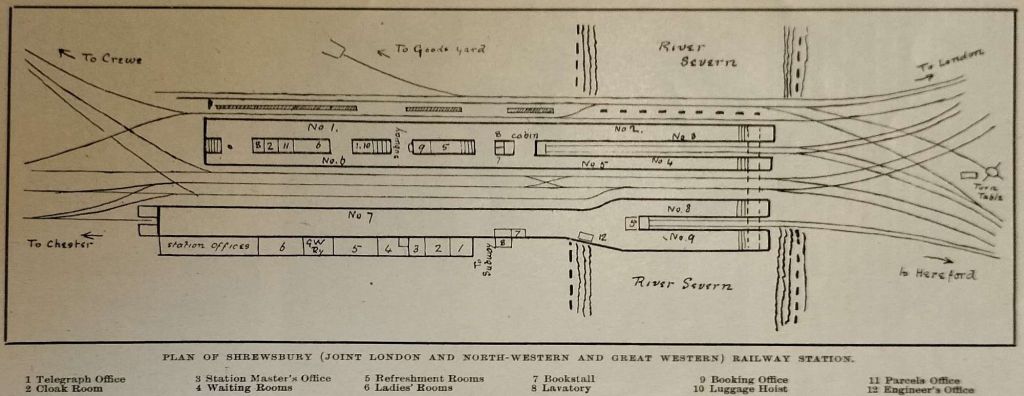

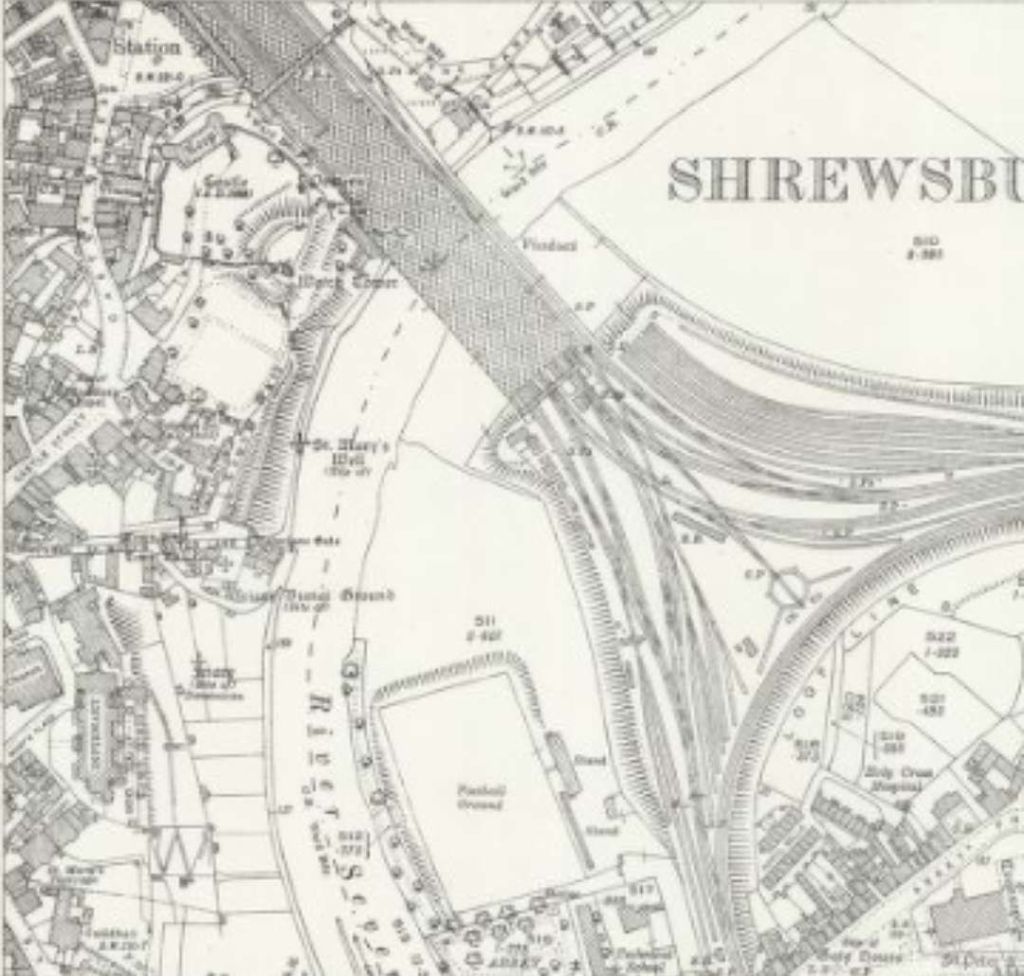

At the Southeast end of the station site, rails predominantly from the South and West converge. At the Northwest end of the station lines predominantly from the North and East meet to enter the Station.

Lawrence highlights the origins of different trains by noting the “places in each direction to and from which there are through carriages.” [1: p461]

From the South and West: London, Worcester, Dover, Kidderminster, Minsterley, Bournemouth, Cheltenham, Portsmouth, Cardiff, Bristol, Swansea, Penzance, Torquay, Weston-super-Mare, Southampton, Carmarthen, and Ilfracombe.

From the North and East: Aberystwyth, Criccieth, Barmouth, Llandudno, Dolgelly, (all of which are more West than East or North), Manchester, Leeds, Liverpool. York and Newcastle, Glasgow and Gourock, Edinburgh, Perth and Aberdeen, Chester and Birkenhead.

Lawrence comments that “these are terminal points, and separate through carriages are labelled to the places named; but, of course, the actual services are enormous: Penzance, for instance, means Exeter, Plymouth, and practically all Cornwall; and London, means Wolverhampton, Birmingham, Leamington and Oxford. And the bulk of these through connections only came into existence – and, in fact, were only possible – after the opening of the Severn Tunnel.” [1: p461-462]

Before 1887, the Midland Railway “had something like a monopoly of the traffic between North and West, and Derby occupied a position analogous to that occupied by Shrewsbury today, but, of course, on a much smaller scale. In 1887, the North and West expresses were introduced by the London and North Western Railway and the Great Western Railway, and then Ludlow, Leo- minster, Hereford, and a host of sleepy old world towns suddenly found themselves on.an important main line.” [1: p462]

From Manchester and Liverpool, Lawrence says, “the new route not only saved the detour by way of Derby, but incidentally substituted a fairly level road for a very hilly one. There are now nine expresses in each direction leaving and arriving at Shrews-bury, connecting Devonshire and the West of England and South Wales with Lancashire and Yorkshire.” [1: p462]

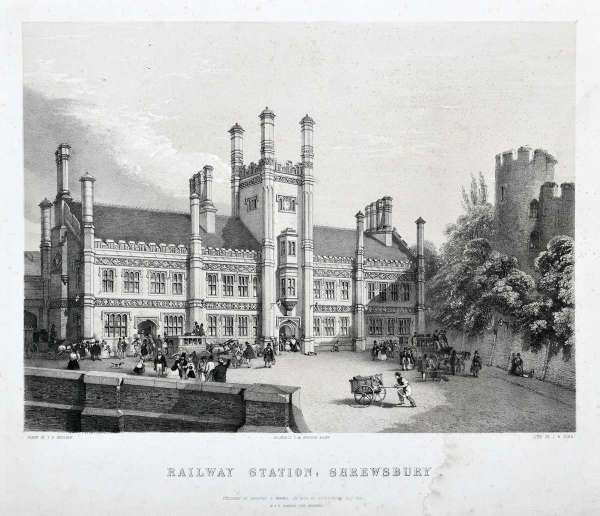

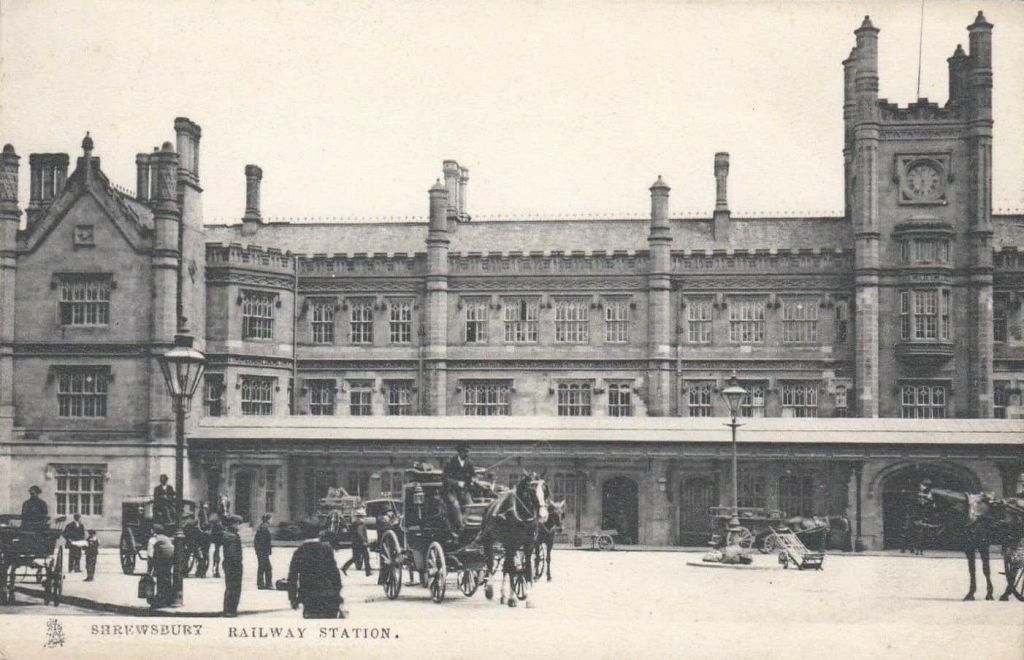

Shrewsbury Station was erected in 1848, and was the terminus of the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway, constructed by Mr. Brassey. It was enlarged in 1855, and practically reconstructed in 1901.

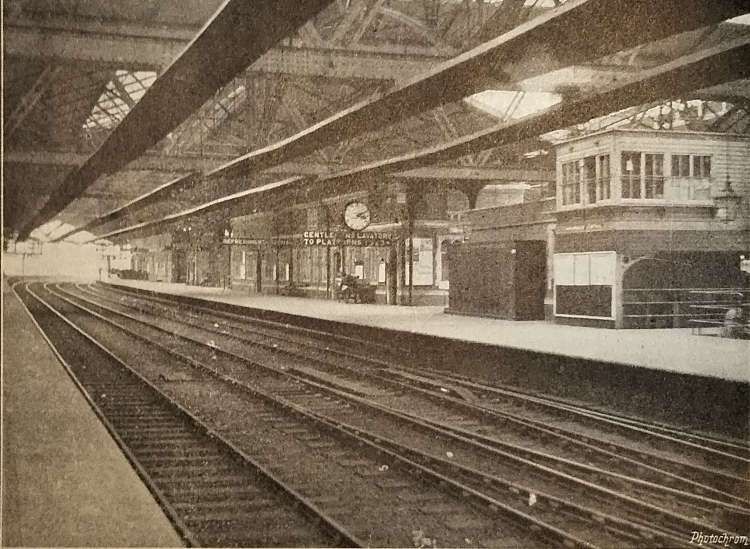

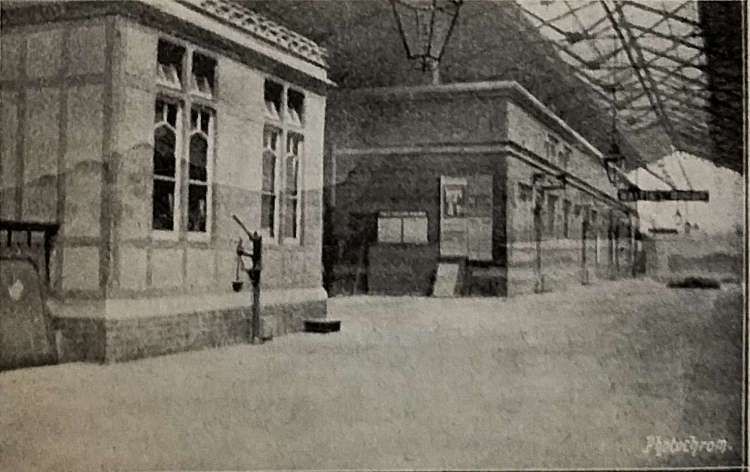

The current Historic England listing for the Station notes that it opened in 1849 and was extended circa 1900. The architect was Thomas Penson Junior of Oswestry. The building is “Ashlar faced with Welsh slate roof. Tudor Gothic style. 3 storeys, though originally two. 25-window range, divided as 4 principal bays, articulated by polygonal buttresses with finials. Asymmetrical, with tower over main entrance and advanced wing to the left. 4-storeyed entrance tower with oriel window in the third stage, with clock over. Polygonal angle pinnacles, and parapet. Mullioned and transomed windows of 3 and 4 lights with decorative glazing and hoodmoulds. String courses between the storeys, with quatrefoil panels. Parapet with traceried panels. Ridge cresting to roof, and axial octagonal stacks. Glazed canopy projects from first floor. Platforms roofed by a series of transverse glazed gables. The building was originally 2-storeyed, and was altered by the insertion of a lower ground floor, in association with the provision of tunnel access to the platforms.” [6]

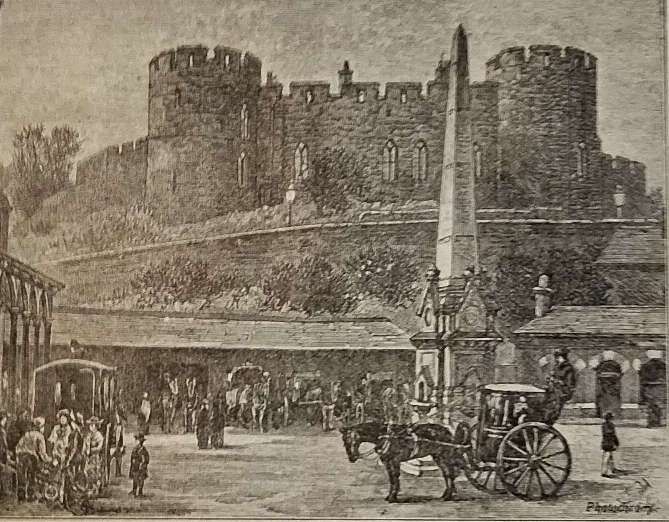

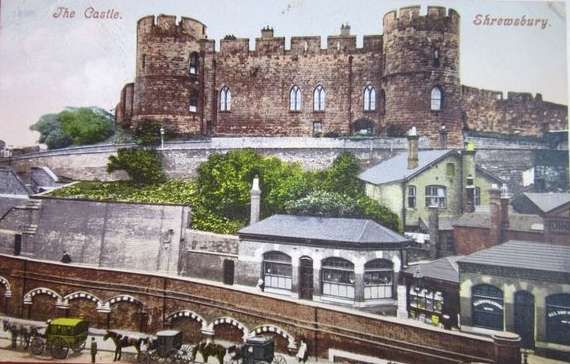

Lawrence says that the building “possesses a handsome façade and is of freestone, in the Tudor Gothic style. Unfortunately, its imposing frontage is not shewn to the best advantage, as the station lies literally in a hole. Previously to 1901 there was direct access from the roadway to the platforms; but the principal feature of the 1901 alteration was the excavation of the square in which the station was built to a depth of 10 or 12 feet, in order to allow the booking offices, parcels offices, etc., to be on the ground floor, under the platforms, and passengers thus enter the station from a subway, wheeled traffic approaching the platform level by means of a slope. On one side frowns the County Gaol, on the other is the Castle, now a private residence. All around and in front are small shops, for the approach is only by way of a back street.” [1: p462]

Shrewsbury Gaol is more normally referred to as Shrewsbury Prison, but you may hear it called ‘The Dana’. It was completed in 1793 and named after Rev Edmund Dana. The original building was constructed by Thomas Telford, following plans by Shrewsbury Architect, John Hiram Haycock.

“William Blackburn, an architect who designed many prisons, also played a part in drawing up the plans for a new prison. It was Blackburn who chose the site on which the prison is built. Blackburn was influenced by the ideas of John Howard, … a renowned Prison Reformer. … Howard visited Shrewsbury in 1788 to inspect the plans for the new prison. He disliked some aspects of the designs, such as the size of the interior courts. … Consequently, redesigns were undertaken by Thomas Telford who had been given the position of Clerk of Works at the new prison the previous year. Shrewsbury Prison was finished in 1793 with a bust of John Howard sitting proudly above the gate lodge. He gives his name to Howard Street where the prison is located.” [7]

Shrewsbury Castle was commissioned by William the Conqueror soon after he claimed the monarchy and was enlarged by Roger de Montgomery shortly thereafter “as a base for operations into Wales, an administrative centre and as a defensive fortification for the town, which was otherwise protected by the loop of the river. Town walls, of which little now remains, were later added to the defences, as a response to Welsh raids. … In 1138, King Stephen successfully besieged the castle held by William FitzAlan for the Empress Maud during the period known as The Anarchy [and] the castle was briefly held by Llywelyn the Great, Prince of Wales, in 1215. Parts of the original medieval structure remain largely incorporating the inner bailey of the castle; the outer bailey, which extended into the town, has long ago vanished under the encroachment of later shops and other buildings. … The castle became a domestic residence during the reign of Elizabeth I and passed to the ownership of the town council c.1600. The castle was extensively repaired in 1643 during the Civil War and was briefly besieged by Parliamentary forces from Wem before its surrender. It was acquired by Sir Francis Newport in 1663. Further repairs were carried out by Thomas Telford on behalf of Sir William Pulteney, MP for Shrewsbury, after 1780 to the designs of the architect Robert Adam.” [10]

At the time of the writing of Lawrence’s article in The Railway Magazine, the castle was owned by Lord Barnard, from whom it was purchased by the Shropshire Horticultural Society. The Society gave it to the town in 1924 “and it became the location of Shrewsbury’s Borough Council chambers for over 50 years. The castle was internally restructured to become the home of the Shropshire Regimental Museum when it moved from Copthorne Barracks and other local sites in 1985. The museum was attacked by the IRA on 25 August 1992 and extensive damage to the collection and to some of the Castle resulted. The museum was officially re-opened by Princess Alexandra on 2 May 1995. In 2019 it was rebranded as the Soldiers of Shropshire Museum.” [10]

Lawrence continues to describe the Railway Station building: “Inside, one notices how the prevailing style of architecture of the front is carried into every detail of the interior. All the windows of waiting room and other platform offions are in the peculiar Tudor style, and the whole interior is graceful and handsome. The excavation of the station square involved the removal of a statue erected to the memory of one of the foremost citizens, Dr. Clement, who lost his life in combating the cholera in the early [1870s]. It was removed to the ‘Quarry’, a place of fashionable public resort.” [1: p462]

“The two main platforms are of considerable length, 1,400 and 1,250 ft. respectively, and each of them can accommodate two trains at once. The station was designed with this object in view, being divided into two block sections by a cabin, from which the whole of the station traffic is controlled. There are seven cabins in all, the most important of which contains 185 levers.” [1: p462-463]

“The lines approaching the station are laid out in curves of somewhat short radius, and the system of o guard rails is deserving of notice. Instead of being in short lengths, as is frequently the case, they are in apparent continuity with the respective facing points, and any derailment seems to be impossible. The new station is built over the river, and consequently the bridge which formerly carried only the permanent way was considerably widened – more than trebled in width, in fact. The platforms are supported by piers driven 25 ft. below the bed of the river by hydraulic pressure.” [1: p463]

Lawrence continues: “Looking across the river, the stationmaster’s house, ‘Aenon Cottage’ it is now called, is seen on the opposite bank, a house which has had a very chequered history. It started life as a thatched cottage; then it became a public house; then a ‘manse’, the residence of the Baptist minister. Then it was altered and enlarged and afforded house room for the Shropshire Union Railway and Canal Offices, and has now entered upon another phase of its railway history as the residence of Mr. McNaught, the stationmaster.” [1: p463] I have not been able to determine the exact location of this property.

Lawrence shares details of McNaught’s employment history with the railways, including periods as Stationmaster at Craven Arms and Hereford before arriving at Shrewsbury in 1890. Under McNaught at Shrewsbury were a joint staff of 160, including 16 clerical and 25 signalmen. Additional non-joint staff included clerical staff in the Superintendent’s office and the carriage cleaners.

At Shrewsbury there were locomotive sheds of the LNWR (57 engines and 151 staff) and the GWR (35 locomotives and about 110 staff).

The station was 171.5 miles from Paddington, the fastest scheduled journey was 3 hr 28min. The route via Stafford to London was 9 miles shorter than the GWR route, the fastest scheduled train in 1905 did that journey in 3hr 10min.

Lawrence notes that “the really fast running in this neighborhood is that to be found on the Hereford line, the 50.75 miles being covered in 63 min.” [1: p464]

Lawrence comments that beyond the station site, “The town of Shrewsbury is not the important place it once was. … Shrewsbury was the centre whence radiated a good deal of warlike enterprise. All this glory has departed, and Shrewsbury has not been as careful as its neighbour, Chester, to preserve its relics of the past. The walls have almost gone, railway trucks bump about on the site of the old monastic buildings, public institutions of undoubted utility but of very doubtful picturesqueness have replaced abbey and keep and drawbridge and its very name has disappeared into limbo. … (‘Scrosbesberig’).” [1: p465]

But, it seems that its importance as a railway hub in someway makes up for other losses of status: During a typical 24 hour period, “there are 24 arrivals from Hereford, 21 from Chester, 18 from Crewe, 18 from Wolverhampton, 13 from Stafford, 7 each from Welshpool and the Severn Valley, 4 from Minsterley, and 2 local trains from Wellington. There are thus 114 arrivals, and the departures are 107, making a total of 221. But a considerable number of these trains break up into their component parts when they reach Shrewsbury, and are united with the fragments of other trains in accordance with the legend on their respective destination boards, so that the total number of train movements is a good deal in excess of the nominal figure.” [1: p465]

Lawrence talks of Shrewsbury as the starting point for GWR trains to make a vigorous attack upon North Wales and similarly as the starting point for their rivals to make a descent upon South Wales. For 115 miles, all the way down to Swansea, the they had local traffic to themselves. Trains ran on the Shrewsbury and Hereford Joint line for twenty miles, as far as Craven Arms, a journey which took about half-an-hour. Trains then commenced on a leisurely run of 3 hours 5 min to 4 hours 40 min. Much of the line was single and stops were numerous. Lawrence remarked that, in the early part of the 20th century, “the fastest train from Swansea stops no less than fourteen times, eight booked and six conditional. This is the favourite route from the north to Swansea, for the scenery along the line is pretty, and, as far as alignment goes, it is much more direct than any other, although the Midland obligingly book travellers via Birmingham and Gloucester.” [1: p466]

Lawrence continues: “The only purely local service in and out of Shrewsbury is that to the little old-world town of Minsterley, 10 miles away, served by four trains each way daily. … The Severn Valley branch connects Shrewsbury with Worcester. The latter city is 52.25 miles away, but there is no express running. It forms no part of any through route. … Two hours and a half is [the] … allowance for 52 miles.” [1: p466-467]

Of interest to me is the time Lawrence quotes for the 63 mile journey from Manchester to Shrewsbury, 1 hour 45 minutes. The shortest train journey from Manchester to Shrewsbury in the 21st century is from Manchester Piccadilly to Shrewsbury, which takes about 1 hour and 9 minutes, although a more typical journey would take more like 1hour 40 minutes. The distance is, today, quoted as 57 miles. There are currently 20 scheduled services on a weekday (15 of which are direct) from Manchester to Shrewsbury. In the opposite direction, there are 37 scheduled rail journeys between Shrewsbury and Manchester Stations (with 17 being direct).

Improvements to Shrewsbury Station Quarter

In 2024/25 Shropshire Council is undertaking work in front of Shrewsbury Railway Station. Work began in June 2024. [20]

Two artists impressions of the work being done in 2024/25 conclude this look at Shrewsbury Station at the start of the 20th century.

References

- J.T. Lawrence; Notable Railway Stations, No. 34 – Shrewsbury: Joint London and North-Western Railway and Great Western Railway; in The Railway Magazine,London, December 1905, p461-467.

- https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/railway-station-shrewsbury-338500, accessed on 20th September 2024.

- https://es.pinterest.com/pin/shrewsbury-railway-station-before-extension-in-2024–608830443403748397, accessed on 20th September 2024.

- https://walkingpast.org.uk/the-walks/walk-1, accessed on 20th September 2024.

- https://parishmouse.co.uk/shropshire/shrewsbury-shropshire-family-history-guide, accessed on 20th September 2024.

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1246546?section=official-list-entry, accessed on 20th September 2024.

- https://www.shrewsburyprison.com/plan-your-day/history, accessed on 29th September 2024.

- https://www.ebid.net/nz/for-sale/the-castle-shrewsbury-shropshire-used-antique-postcard-1907-pm-215879875.htm, accessed on 20th September 2024.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shrewsbury_Schloss.JPG, accessed on 20th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shrewsbury_Castle, accessed on 20th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=52.71185&lon=-2.74940&layers=168&b=1&o=100, accessed on 20th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/121150019, accessed on 20th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/121150052, accessed on 20th September 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2202736, accessed on 22nd September 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2165363, accessed on 22nd September 2024.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/justinfoulger/53692950655, accessed on 22nd September 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2540220, accessed on 22nd September 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/6374074, accessed on 22nd September 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5153766, accessed on 22nd September 2024.

- https://newsroom.shropshire.gov.uk/2024/06/work-to-begin-to-improve-shrewsbury-railway-station-area, accessed on 22nd September 2024.