Back in November 2000, Michael S. Elton wrote about the Killin Branch in BackTrack magazine. The featured image for this article is the front cover of the November 2000 (Volume 14 No. 11) issue of the magazine. It depicts ex-Caledonian Railway Class 439 0-4-4T No. 55222 shunting at Killin on 4th September 1958, © Derek Penny. [1]

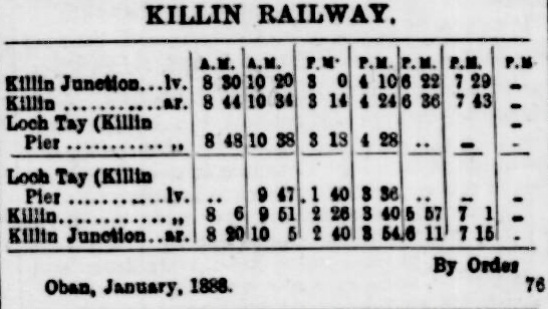

“At first glance appearing to be no more than an offshoot of the picturesque and spectacular Callander & Oban Railway, the Killin Railway was a wholly independent company in its own right for the first 37 years of its working life. The Killin Railway Company endured for almost all of its independent years under the patronage of one of Scotland’s wealthiest men. The local people promoted the village railway company in 1881 and the line was run under their management from its official opening on 13th March 1886 until its independence was reluctantly conceded to the LMS from 1st June 1923. In absorbing the Killin Railway Company the LMS accepted some £12,000 of debt accumulated over the years of its independence and paid the remaining shareholders just 8% of the face value of their original investment, in full settlement of the enforced transaction. During the years of independence and before they were absorbed into the LMS, the train services of both the Killin and the adjacent Callander & Oban Companies were worked by the Caledonian Railway Company as integral parts of its system.” [1: p624-625]

Gavin Campbell, the Marquis of Breadalbane & Holland held 438,558 acres of land in his estates in Argyllshire and Perthshire, spread across much of central Scotland. He was the prime mover in the development of the branch line to Killin Village.

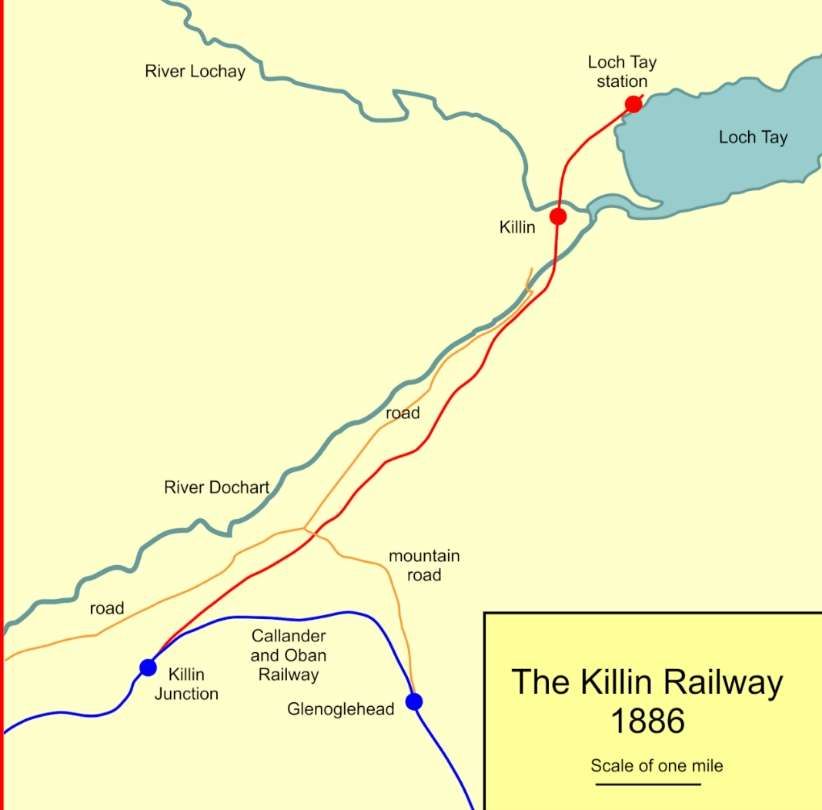

Wikipedia tells us that “On 1st June 1870, the Callander and Oban Railway opened the first portion of its line. Shortage of cash meant that the original intention of linking Oban to the railway network was to be deferred for now. The line opened from the former Dunblane, Doune and Callander Railway at Callander to a station named Killin, but it was at Glenoglehead, high above the town and three miles (5 km) distant down a steep and rugged track.” [2][3]

“The difficult local terrain prevented any question of the line to Oban passing through Killin, and local people were for the time being happy enough that they had a railway connection of a sort; indeed tourist trade was brought into the town. The Callander and Oban Railway had in fact been absorbed by the Caledonian Railway but continued to be managed semi-autonomously. The Caledonian was a far larger concern that had money problems, and priorities, elsewhere. Nevertheless, as time went on, extension of the first line to Oban was resumed in stages, and finally completed on 30th June 1880.” [2]

Elton tells us that, “At the time that the story of the village railway began, Killin was a remote rural community that had for many years relied for its prosperity on providing a market place for the produce of the Highland farmers from the surrounding lands. Those farmers were largely tenants of the Marquis and although there is no doubt that he had their well-being in mind as well as that of the villagers of Killin, the commercial possibilities were also under his consideration when he moved the promotion of the village railway and concurrently founded the Loch Tay Steamboat Company. The village of Killin also served as a convenient overnight stop for animal drovers and their herds consisting predominantly of sheep. Situated near the lower, western, end of Loch Tay, a number of ancient overland paths met naturally near the village.” [1: p625-626]

“The traditional commerce of Killin had been seriously eroded when, in 1870, the Callander & Oban Railway had reached the head of Glen Ogle. … The C&O was able to offer to the traditional customers of Killin a more direct access to the great livestock markets of southern Scotland. The station at the head of Glen Ogle, given the name Killin, was the northern terminal of the C&O from 1st June 1870 until August 1873. On that date the line was extended for seventeen miles to a temporary terminal at Tyndrum. From Tyndrum the C&O line eventually reached Oban, being ceremonially opened to that place on 30th June 1880. Prior to that, the Highland Railway Company had built a branch line, from its Perth-Inverness main line at Ballinuig, to Aberfeldy and this line also attracted livestock trade away from Killin. It was at one time believed locally that the branch line would be extended from Aberfeldy to Kenmore and perhaps on to Killin itself but this was never seriously considered by the Highland Company. Nevertheless, as built, the branch line gave better and cheaper access to the immense markets of Perth and Edinburgh and attracted traffic from the C&O terminal at Glenlochhead.” [1: p626]

“The people of Killin petitioned the Callander and Oban company for a branch line, but this was refused, and when the Caledonian Railway itself was persuaded to obtain Parliamentary authority to build the branch, the Bill failed in Parliament.” [2]

Under the leadership of the Marquis of Breadalbane, the people of Killin decided to build a railway themselves. “The first meeting of the local railway took place on 19th August 1882, in Killin. Making a branch to join the Callander and Oban [Railway (C&O)] at its “Killin” station would involve an impossibly steep gradient, but a line was planned to meet the C&O further west and at a lower altitude. Even so, the branch would be four miles (6.4 km) long with a gradient of 1 in 50. It could be built for about £18,000. At the Killin end, the line would be extended to a pier on Loch Tay, serving the steamer excursion traffic on the loch.” [2][4][5]

Elton tells us that before the 19th August 1882 meeting took place, the Marquis of Breadalbane “sought the advice of civil engineer John Strain. In 1877 Strain had successfully undertaken to survey and engineer the last section of the C&O. This 24 miles of railway, from Dalmally to Oban, had presented him with many difficulties. Following Strain’s recommendation Breadalbane explained to the villagers at the meeting that the proposed new line would branch from a junction on the C&O some 2½ miles down the line from the existing Killin station at the head of Glen Ogle. A new station would be placed within the village itself and the line would be extended 1 miles to a station on the shore of Loch Tay. A pier for berthing the steamships plying the loch was to be built with facilities for handling passengers, live-stock and general cargo, adjacent to the Loch Tay station. The Marquis had formed the Loch Tay Steamboat Company, whose steamships and those of succeeding companies would serve on the loch until 1939.”

The ruling gradient of the proposed new line would be a demanding 1 in 50. John Strain had estimated the cost of building the line at £18,000 (£3,428 per mile). Detailed forecasts of the potential traffic indicated that only a modest income could be expected for distribution to shareholders (£365 per annum). The Marquis “invited those attending the meeting to invest in the railway, adding that he would match pound for pound the money raised. … In the three weeks after the initial meeting no more than £370 was subscribed to the funds of the new company. Mr. A. R. Robertson, who had been appointed Company Secretary, estimated that the total potential investment from the area was unlikely to exceed £4,000. This figure assumed the most strenuous of canvassing and included the promise of £1,000 from Sir Donald Currie, a resident of Aberfeldy. Mr. Robertson, as the manager of the Killin branch of the Bank of Scotland, was in a unique position to assess the probable local investment.” [1: 627]

There was a clear local determination to bring the scheme to fruition. In kind commitments were made locally in exchange for shares in the new line. The Marquis “donated all of the required land and sleepers for the track whilst the Caledonian and C&O Companies supplied the rails, all in return for shares in the village company. The C&O Company itself bought 1,200 shares and that encouraged many smaller investors. The Caledonian Railway arranged to work the line for the first three years for 55% of the receipts but stipulated that the annual turnover should not be less than £2,377. There was not one objector to the scheme and the potentially ruinous promotion of a Parliamentary Bill was thus avoided. Instead, only a Board of Trade Certificate for the construction was required and that was received on 8th August 1883. Prior to that the embryonic Killin Railway Company had already sought tenders to construct the line. The board of directors consisting of Lord Breadalbane himself, Charles Stewart, Sir Donald Currie, John Willison and Col. John Sutherland obtained nine quotations in all. These ranged from the highest at £22,442 6s 3d down to one of £13,783 8s Od, quoted by Messrs. Α.& K. MacDonald of Skye. The company secretary, who had no profound knowledge of railways, calculated that if the directors accepted the lowest tender, the total cost of getting the line into full working condition would be £28,552. The total assets available to the company at that point in time, having exhausted all sources and allowing for borrowings of £5,200, had reached an impressive £20,801. John Strain was again consulted and advised that the line could not be built for anything like the price of the lowest tender. Nevertheless, the temptation of saving such capital was too great and the MacDonalds’ tender was accepted by the village board.” [1: p627]

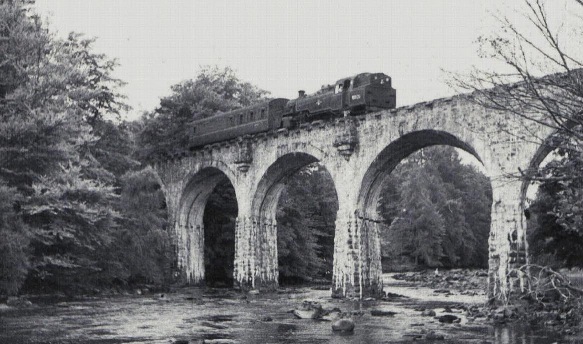

Inevitably, work on the project gradually fell behind and ultimately the MacDonald’s contract had to be terminated. The work was passed to John Best, of Glasgow. “Towards the end of February 1885, Strain reported that 73% of the earthworks and 84% of the culverts, creeps and bridgework had been completed.” [1: p628] The Board of Trade inspection eventually took place in early 1886 and the ceremonial opening took place on 13th March 1886. Public services on the line commenced on 1st April 1886.

The Line

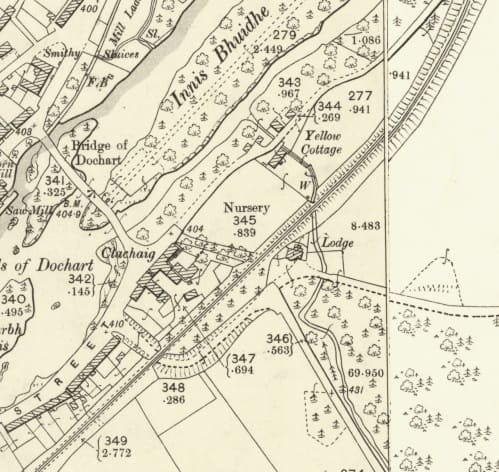

Looking at the branch, we start at the junction station. …

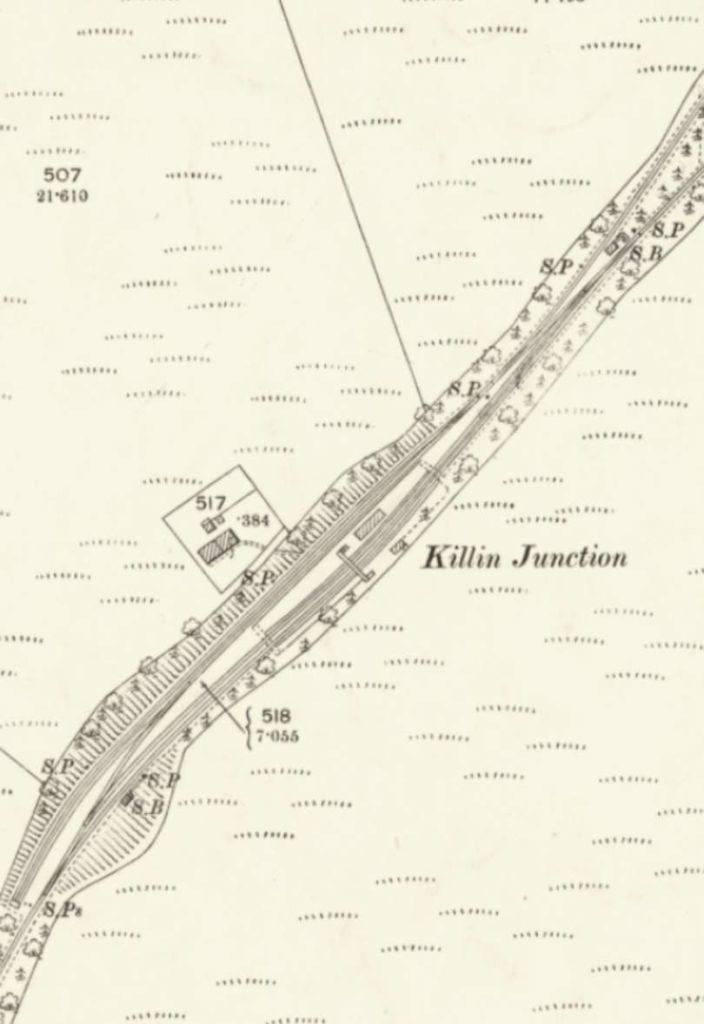

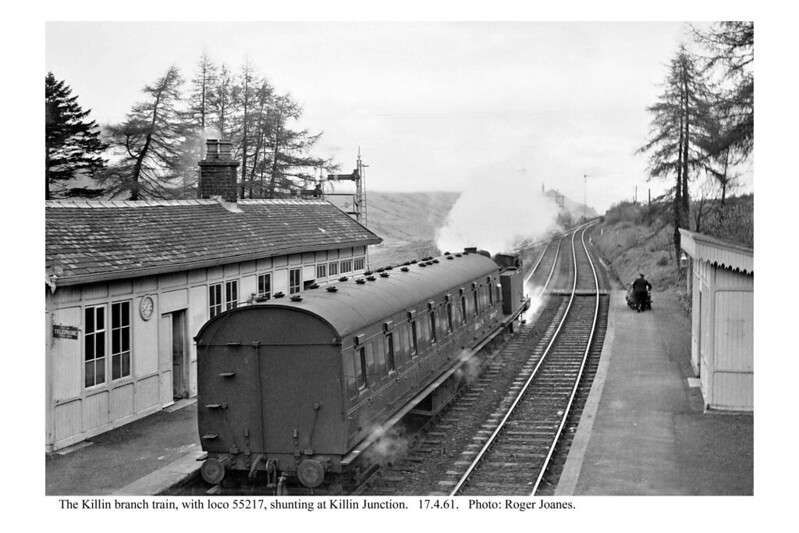

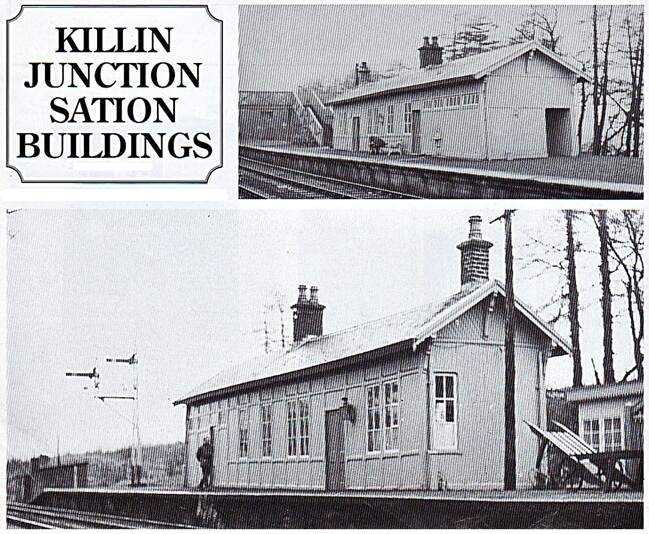

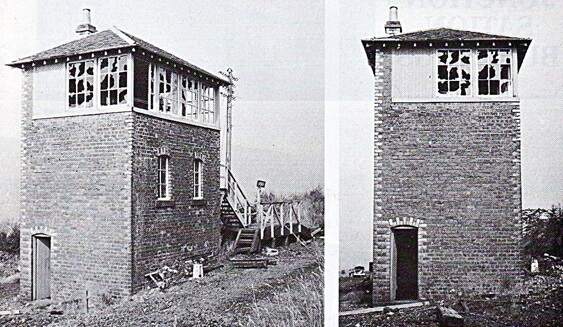

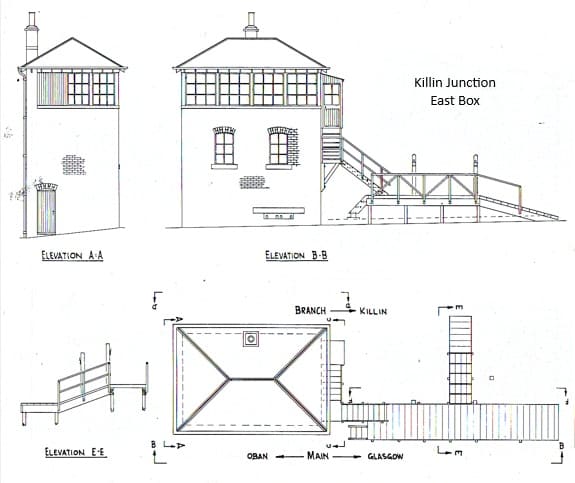

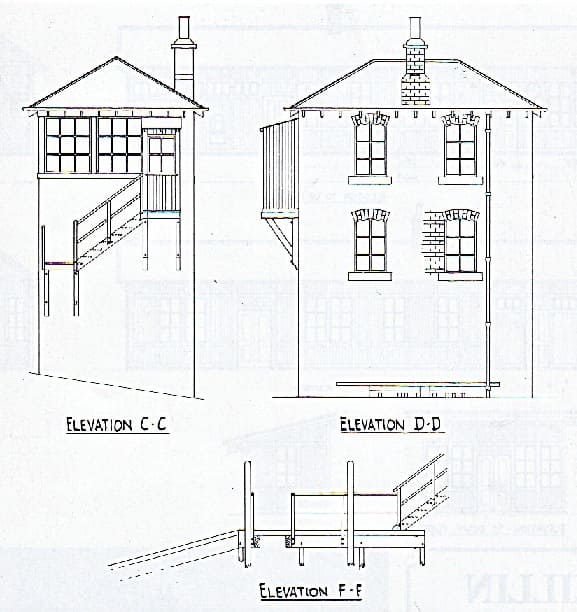

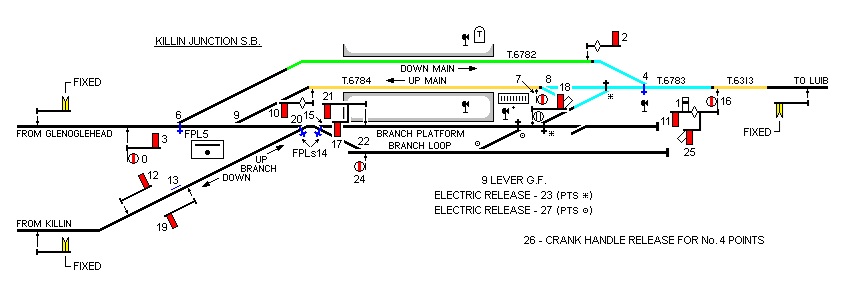

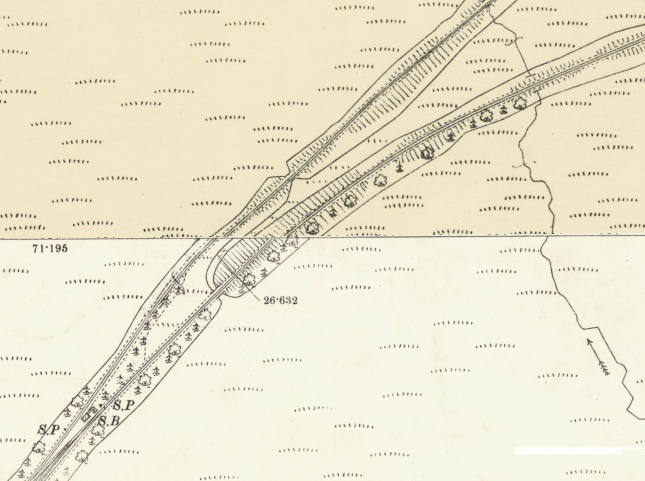

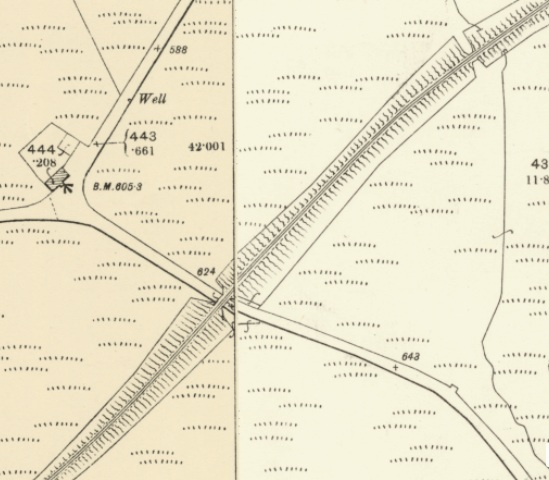

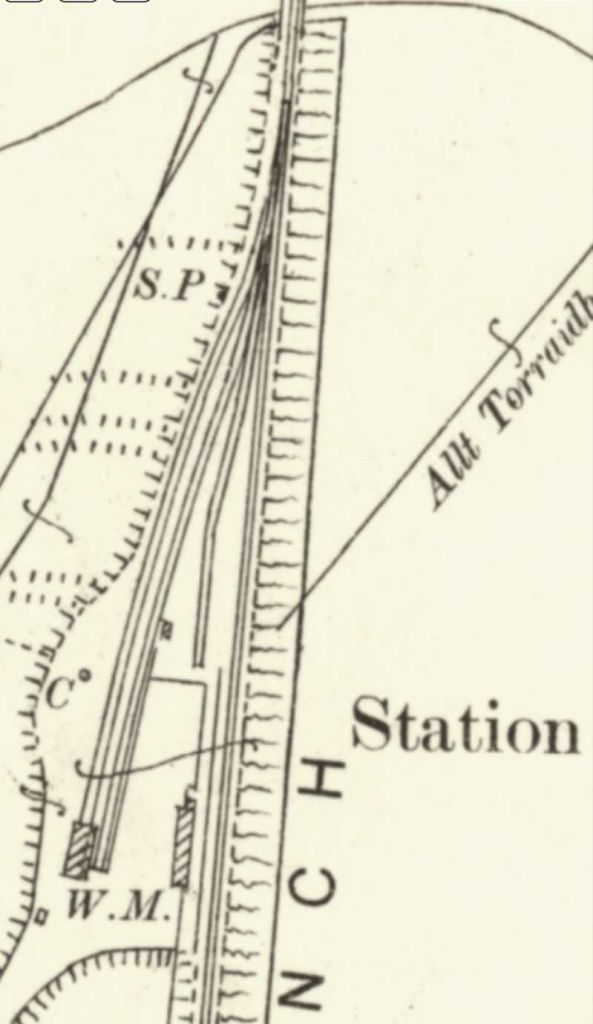

The junction station on the C&O was half-a-mile from the nearest road and was far more complex than required. The station was of substantial proportions. “A single and an island platform provided three faces, two of which served the up and down lines of the C&O respectively. The remaining face … was kept exclusively for the use of the village line train. Two sidings and a crossover system were installed on the village line side. A passenger overbridge was built in 1908, while two cottages for station staff and a goods shed completed the facilities. The station complex was controlled by two signal boxes containing a total of 48 levers, 22 in the West box and 26 in the East. The junction station was set on a gradient of 1 in 138, at an elevation of about 800ft above sea level.” [1: p630]

Elton’s date for the construction of the footbridge is called into question by the OS Map extract below which was surveyed in 1899 and shows a foot bridge already in place at that time.

In 1935, the West Signal Box at Killin Junction was closed and the East Signal Box took control of the whole station layout. On Saturday 22nd October 1938, “Lt. Col. Wilson (Ministry of Transport) reported that the West Junction box had been closed and the facing points at the southern end of the main crossing loop were now motor operated by primary battery from the East Junction box, with an auxiliary tablet instrument for the section to Luib provided on the Down platform. To provide connections at the south end of the station Branch platform, a new 9-lever ground frame was provided, electrically controlled from the East Junction box, and which also slotted the running signals which applied to movements into and out of the Branch platform at its south end. Such moves were relatively infrequent, although the Branch Platform line formed a convenient third loop for trains crossing. The platform was mainly used for the shuttle service on the Killin Branch, which was worked by a train staff and one engine in steam. On account of the long and steep downward gradient towards Killin, interlaced lines named “live” and “dead” roads were formerly provided, with facing points at both ends. Ascending trains used the left-hand interlaced line, in which there were self-acting catch points. These “live” and “dead” roads had now been removed. Shunting was prohibited along the branch unless the engine was at the lower end. A similar prohibition applied to the single line towards Luib, where the gradient also fell steeply. The signal arrangements were as on the plan, with three new track circuits, separately indicated in the East Junction box, which had a frame of 28 levers, all in use with correct locking and control.” [66]

More photographs of the station can be found on Ernie’s Railway Archive on Flickr …. here, [10] here, [11] here, [12] here, [13] here, [14] here, [15] here, [16] and here. [17]

In the image above, the Callander and Oban Railway is on the right of the signal box, the Killin Branch is to the left of the box. The line down to Killin was steeply graded (1 in 50) down to the village.

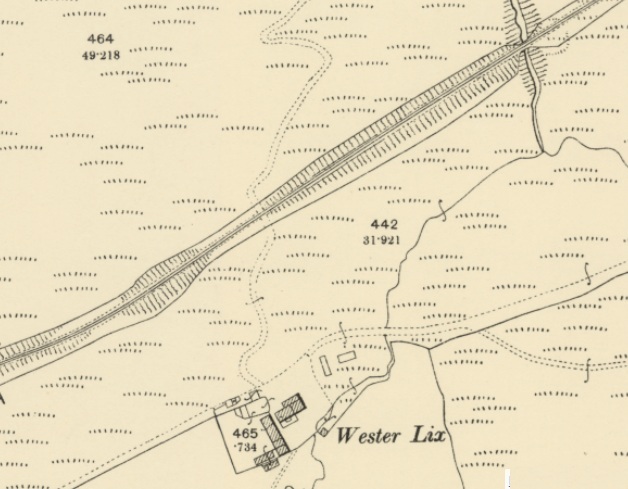

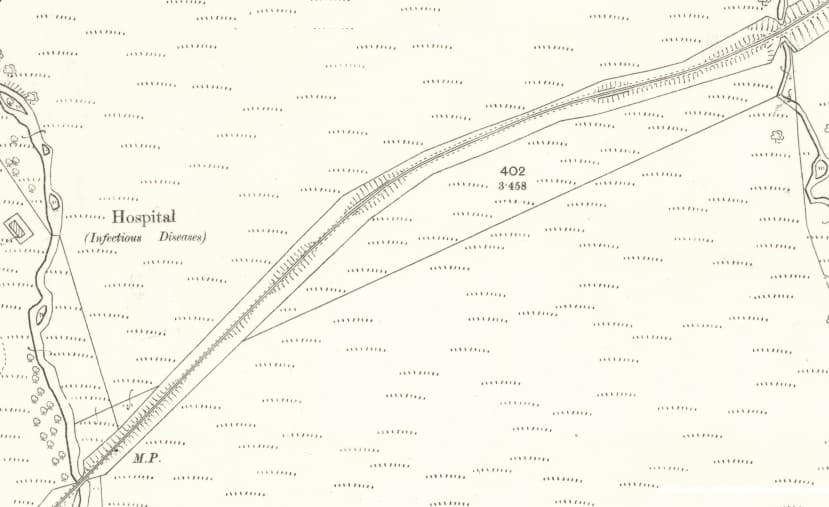

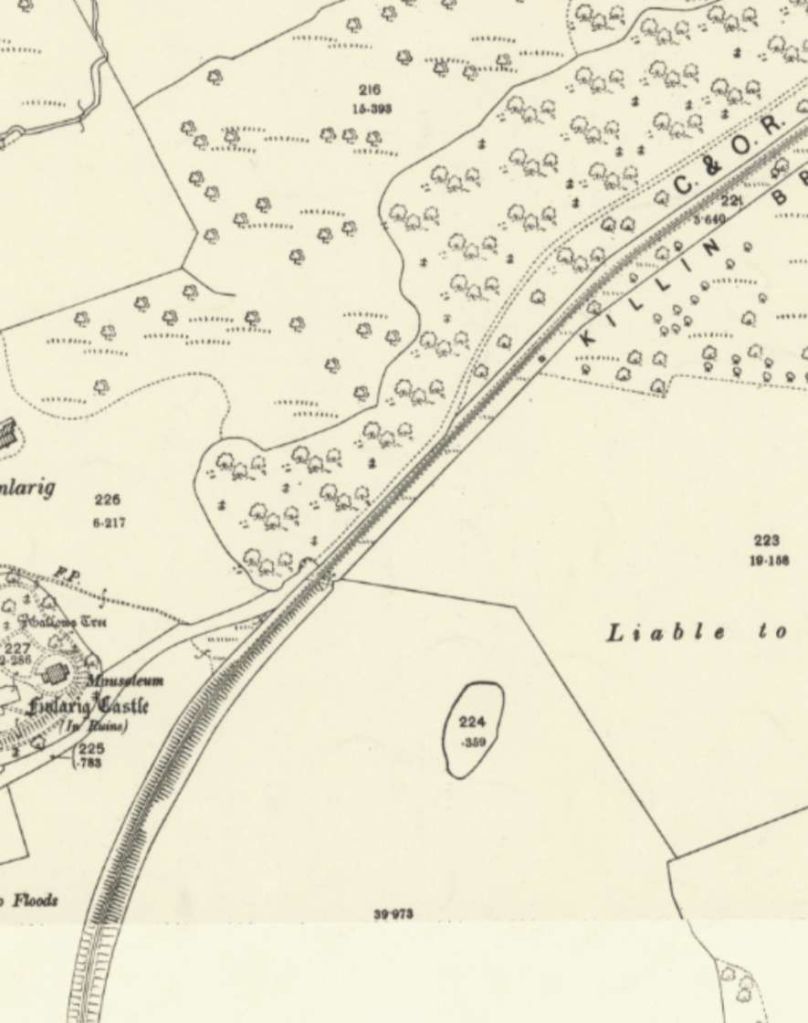

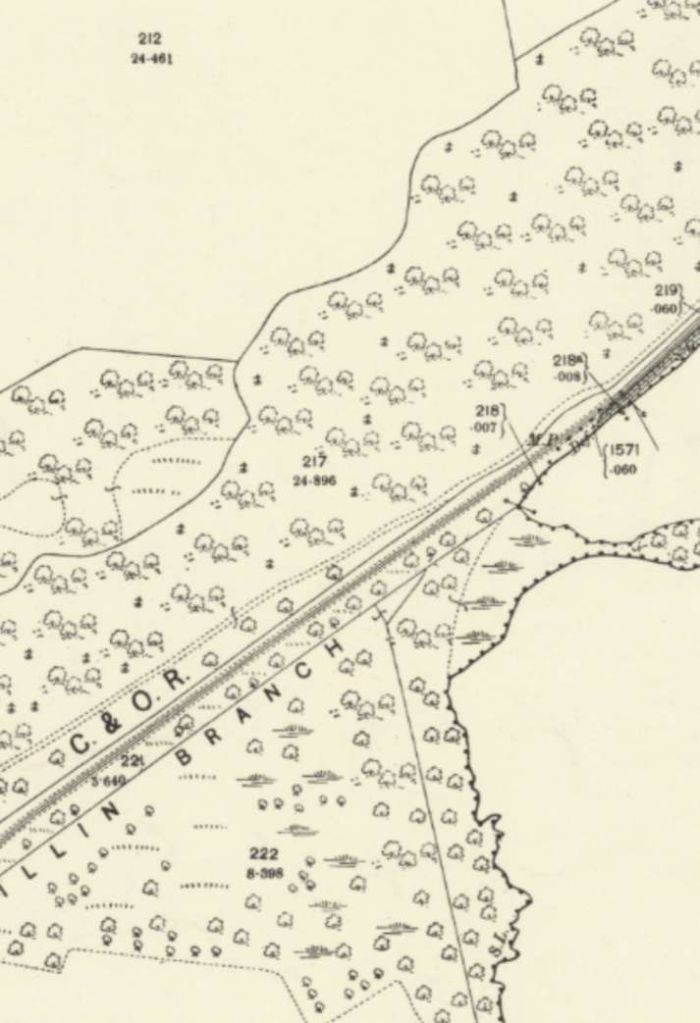

The branch continued heading Northeast towards Killin, passing to the North of Wester Lix and bridging a minor tributary of the River Dochart.

To the Northeast of the main road the railway remained predominantly on embankment. A cattle creep sat a few hundred metres Northeast of the road bridge. It can be seen in the top right of the last OS Map extract. The next significant structure carried the line over the Allt Lairig Cheile, another tributary of the River Dochart.

The large building which appears on the satellite image above is Acharn Biomass.

Acharn Biomass Plant is an electricity production plant owned by Northern Energy Developments. It has a 5.6 MW capacity. [25]

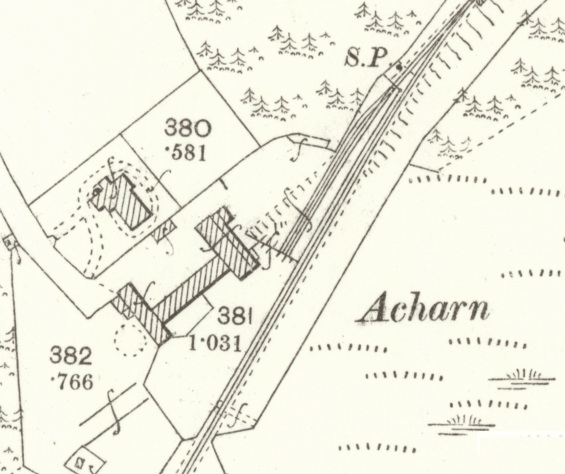

A short distance Northeast along the line, a pair of sidings were provided at Acharn. This Acharn is not to be confused with a hamlet of the same name on the south shore of Loch Tay towards its East end. That Acharn is a hamlet in the Kenmore parish of the Scottish council area of Perth and Kinross. It is situated on the south shore of Loch Tay close to its eastern end. The hamlet was built in the early 19th century to house workers from the surrounding estates. [27]

This Acharn is adjacent to Acharn Forest. Most of the forest is a mixed conifer plantation with pockets of broad-leaved woodland and open moorland. [28] The sidings at Acharn served the farm and were situated on the north side of the single line, they opened with the Killin Railway in 1886. The sidings ground frame was released by the branch train staff. Owing to the gradient, the sidings were only worked by Down direction trains. They were removed in 1964. Colonel Marindin (Board of Trade – 12th February 1886) noted in his inspection of the Killin Branch, that there were no main line signals at the location of the Sidings. [30]

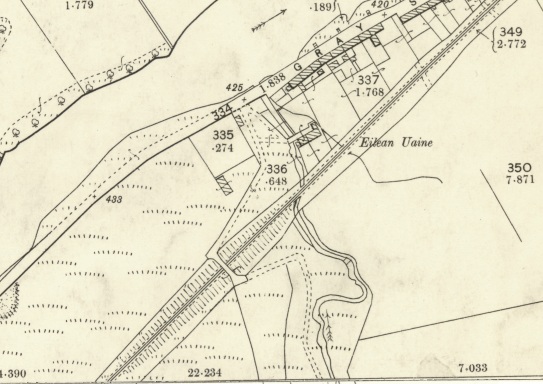

The line continued to run Northeast on a 1 to 50 grade passing under an accommodation bridge as the village approached.

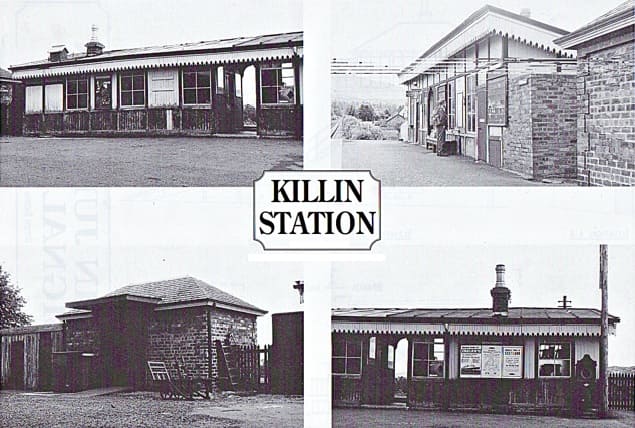

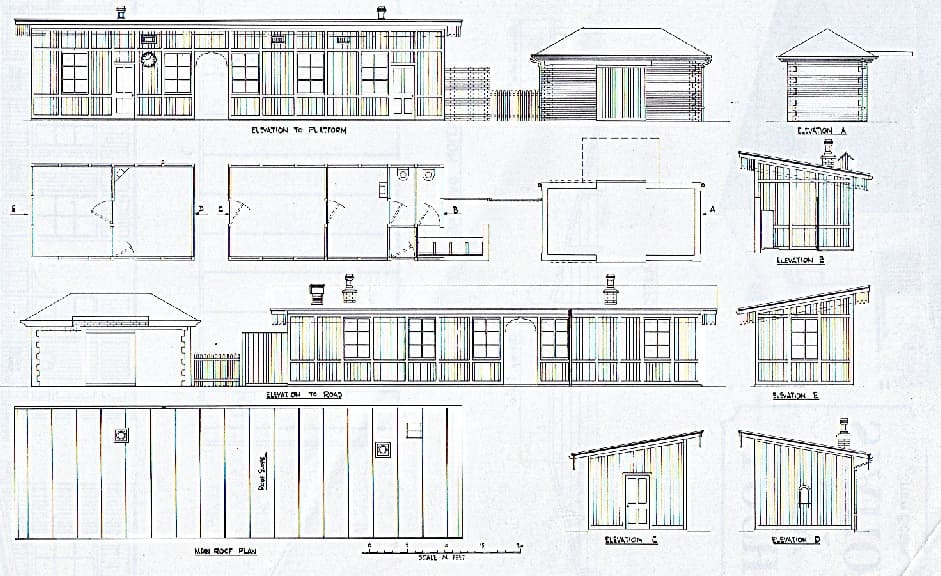

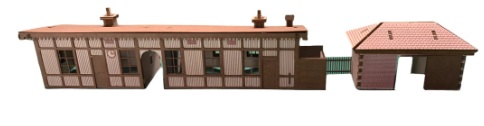

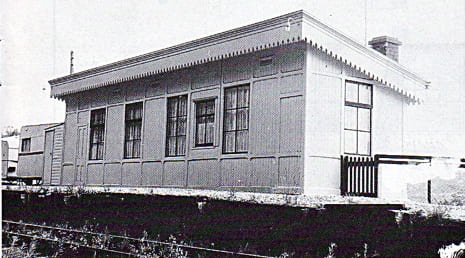

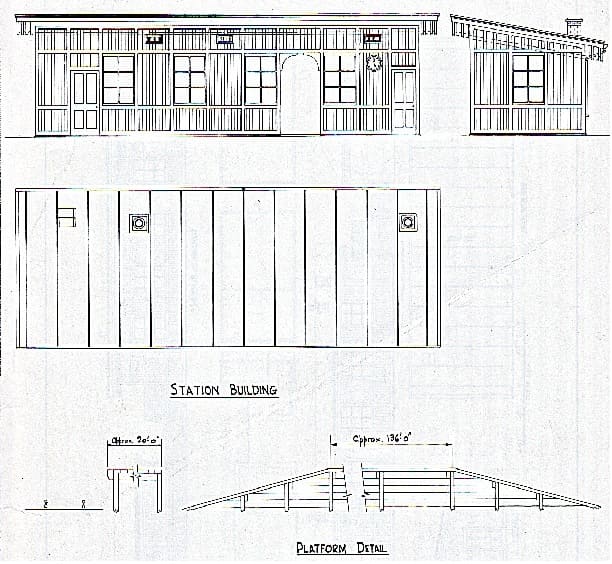

Elton describes the station at Killin: “three sidings were provided for the expected livestock and freight traffic and we’re controlled by a ground frame. The station buildings were of a simple nature (as they were at Loch Tay) and the station itself was set on a gradient of 1 in 317. Two cottages were provided in the village for railway staff.” [1: p630]

A camping coach was positioned here by the Scottish Region from 1961 to 1963. [64]

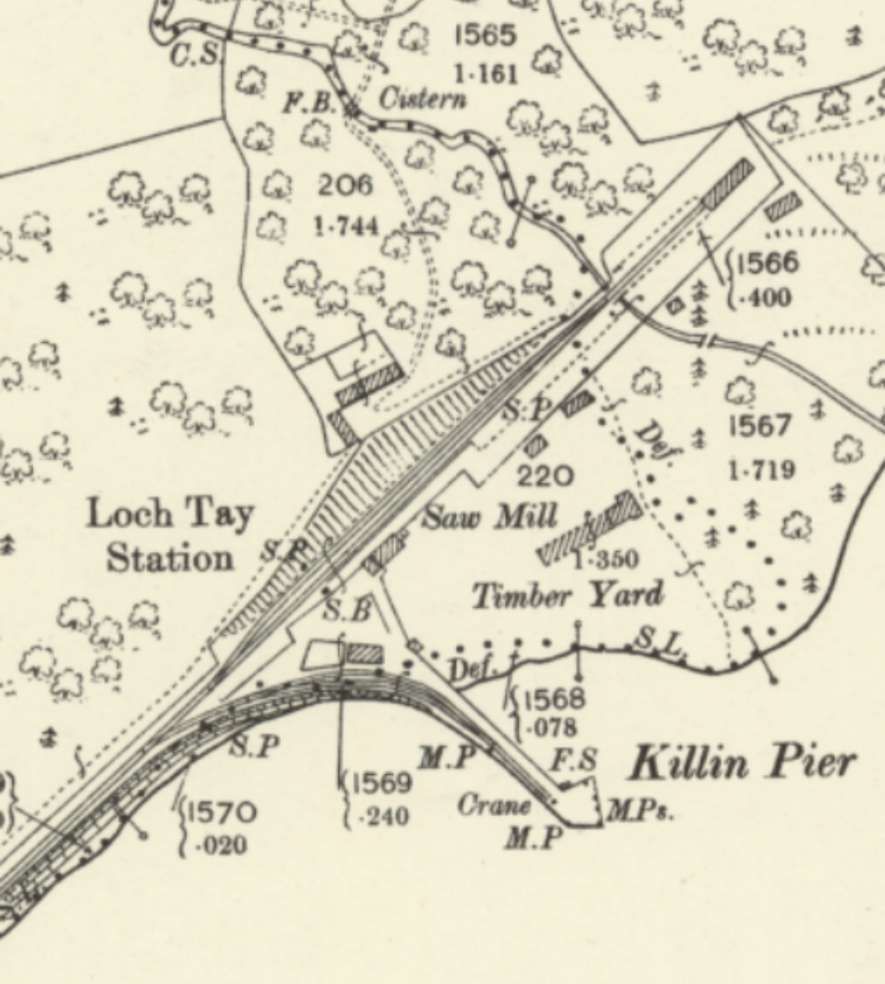

Elton continues: “The line extended a further 1.25 miles to a single platform at Loch Tay. A branch a little before Loch Tay station extended on a sharp curve along the pier that served the steamers.” [1: p630]

Again, Elton continues: “At Loch Tay was a small engine shed, with water and fuel facilities for the locomotive working the branch. Considering that one of the objectives in building the line was to recapture the lost livestock traffic, nothing was done to provide learage accommodation for farm animals at either the village or the junction stations. Naturally, this discomfited passengers using the line but in any case the way to the big livestock markets was many miles further over the C&O than from Aberfeldy and the animal traffic was never recovered to any great extent.” [1: p630]

Locomotives, Rolling Stock and Operation

The Killin Pug

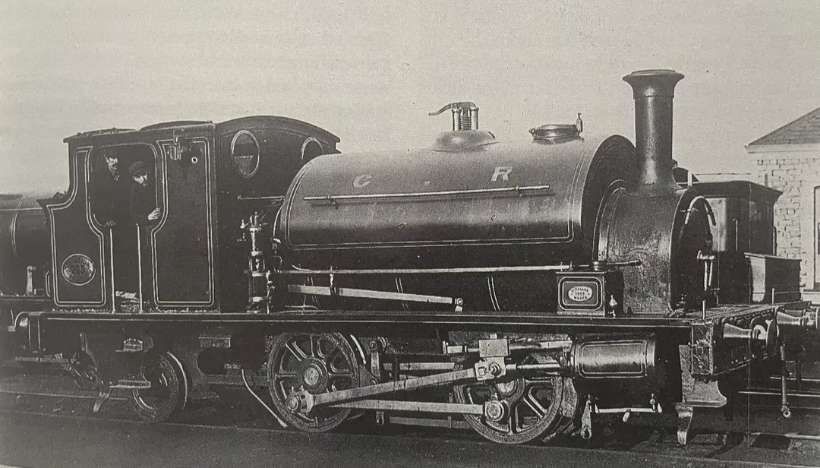

The Callander Heritage Centre writes of the locomotive above: “In 1885, Caley locomotive designer and engineer, Dugald Drummond, was commissioned to build a special small tank engine which could be used on the Killin branch. After much research into the line, its gradients, curves and so on he decided upon an 0-4-2 saddle tank type locomotive. The design was based on the popular 0-4-0 “Pug” tanks which were widely used for dockside and colliery work. Once the plans were prepared two such locomotives were built at the Caledonian Railways St Rollox locomotive works in Glasgow before being sent up to the branch. … With its tall, straight stovepipe chimney the little engine soon became known as the coffee pot amongst the local villagers who would often gather on the station platforms when the train was due just to marvel at its sheer size and power. It may have only been a small engine by comparison to the larger mainline giants, but to the people of Killin nothing could have beaten their blue pug.” [55]

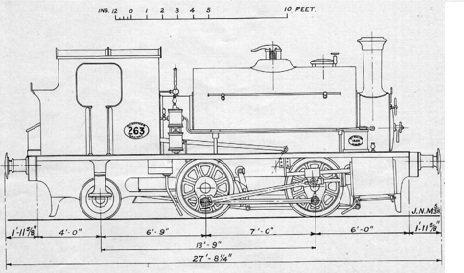

Elton tells us that the original intention had been for 0-4-0ST locos to provide the motive power but Drummond quickly became convinced that 0-4-0 wheel arrangement would be inadequate. “The heavy grading of the line, together with the severe curve weight distribution essential on the Loch Tay pier, resulted in the two locomotives being given an 0-4-2ST wheel arrangement. The water and fuel capacities on the engines were increased to assist adhesion on the 1 in 50 ruling gradient and they were fitted with a Westinghouse braking system as an additional safety feature. Built at the Caley’s St. Rollox works, the engines carrying the numbers 262 and 263 – were of distinctive appearance and, in their Caley blue livery, became popular with the Killin villagers. They were known as the ‘Killin Pugs’ but were soon found to be unsuitable for working the village line, both being withdrawn from it as early as 1889. They were found work elsewhere on the Caley system, surviving the groupings and remaining in service almost into nationalisation.” [1: p631]

Thanks to Ben Alder for pointing me to The Model Railway News which carried an article about one of these locomotives written by J. N. Maskelyne in its July 1938 edition. The article was a result of a request made to the LMS for design details of the locomotives. The request resulted in delivery of four large blue prints and a copy of the small official weight-diagram, together with a letter in which regret was expressed that no general arrangement drawing of the engine could be found. The prints showed, respectively, the frames, the cab, the smokebox, and the saddle-tank: on carefully scrutinising these prints, Maskelyne concluded that “in all probability, no general arrangement drawing was ever made. [His conclusion was that] except for the items mentioned above, all the details on this engine were standard, or, at least, common to other types of engines and that the order for her construction was accompanied by a set of blue prints, similar to that which I had received, and a ‘Material List’, setting out all the details required, and referring to drawings already issued to the works.” [58: p184]

With the aid of the four blue prints, and a photograph, taken by Mr. J. E. Kite, Maskelyne produced general arrangement drawings for the locomotives.

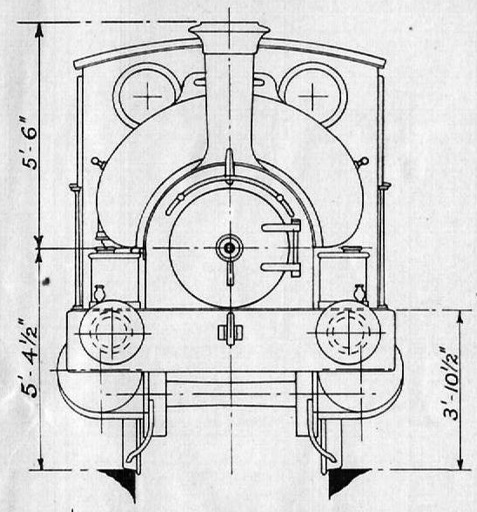

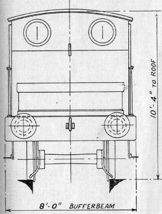

Maskelyne notes that “the dimensions of this engine [were] very small; her coupled wheels [were] 3 ft. 8 in., and the trailing wheels, which [were] of “disc” type, [were] 3 ft. diameter. The boiler barrel [was] 10 ft. 9 in. long, and ha[d] a mean diameter of 3 ft. 8 in. it contain[ed] 138 tubes of 14 in. diameter, and [was] pitched with its centre-line 5 ft. 41 in. above rail level.” [1: p183]

“The firebox inner shell [was] 3 ft. 6 in. square, and the grate area [was] 10.23 sq. ft. The heating surface of the tubes [was] 632 sq. ft., and that of the firebox [was] 52 sq. ft., making a total of 684 sq. ft. The working pressure [was] 140 lb. per sq. in. The cylinders ha[d] a diameter of 14 in. and a stroke of 20 in., and the tractive force [was] 10,600 lb. The saddle-tank [held] 800 gallons of water, the bunker 2.25 tons of coal. In working order, the weight [was] 31 tons 4 cwt. 2 qr., with 25 tons 17 cwt. available for adhesion, and the engine [would] take a minimum curve of 41 chains radius. The height of the top of the chimney [was] 10 ft. 10½ in. above rail level.” [58: p183-184]

It became necessary, after just a few months of operation to review the basis on which the C&O provided services on the line. It was abundantly clear after that time that the agreed minimum level of receipts (£2,377 per annum) would not be met. “A new working agreement with the Caledonian came into operation on 1st April 1888. The Caley undertook to work the Killin line at cost initially for a period of five years. Additionally, it agreed to contribute £525 pa towards the general running cost of the village line. In practice the Caledonian deducted the operating costs at source and sent the balance on to the Killin company.” [1: p631]

Late in the 1880s, “the ‘Pugs’ were replaced by altogether more powerful tank engines of 0-4-4T wheel configuration, again designed under Dugald Drummond. … Two were allocated for use on the Killin line and locomotives of this type and their subsequent developments provided most of the motive power on the village line until the 1950s.” [1: p631]

A view of sister locomotive 0-4-4T No. 55173 can be seen here, © Colin T. Gifford. [57]

In the 1950s, under BR ownership, the Caledonian 0-4-4Ts were replaced by a variety of different locomotives. Ultimately the standard service on the line was provided by standard BR 2-6-4T 4MT locomotives. This was possible because of the earlier closure of the line Northeast of Killin and there being no need to accept the limitations on weight and wheelbase demanded by the Loch Tay pier. Passenger accommodation on train services was provided by a single four compartment brake coach and services often ran as a mixed train with goods wagons attached to the single passenger-carrying vehicle.

The sponsorship of the short Killin Branch by The Marquis of Breadalbane protected the little line from the worst of the political winds affecting the railway world. He became ill while travelling to a Caledonian Railway board meeting. Elton tells us that he “died at the Central Hotel, Glasgow on 19th October 1922, at the age of 71. His nephew, Mr Iain Campbell, who succeeded to the title, was not disposed to regard the Killin village line as anything other than a financial liability. … The death of the Marquis left the management of the village company in the hands of the two remaining local directors, Messrs. Campbell Willison and Alan Cameron. They were fiercely determined to retain control of their line in the face of what they at first believed was a move to absorb the Killin village line by the Caledonian Company. Ultimately, they received the approach from an organisation, quite unknown to them, calling itself the London, Midland & Scottish Railway. They immediately adopted a defensive position, rejecting an offer which accepted all the accumulated debt of the village company and offered £1 in cash for every £100 of Killin Company stock. The audacity of this rejection, from such a minor outpost of its ‘shotgun’ empire, came as something of a surprise to the LMSR authorities. The villagers did not at first comprehend that an Act of Central Government would ultimately give them no choice in the matter. Nevertheless, after some negotiation the offer to the villagers was eventually raised to £8 per £100 of stock as well as taking on the £12,000 of debt. The Killin Railway Company ended as it had begun with a meeting in the Village Hall. This was held on 19th March 1923 and the takeover was enacted on the following 1st July, on which date the Caledonian and C&O Companies also came under the wing of the LMSR.” [1: p632]

Elton continues: “Under the regime of the LMS the Killin branch, as it now became, changed very little. However, in September 1939, immediately after the outbreak of World War II, the line between Killin Village and Loch Tay was closed to both passenger and freight traffic. The Loch Tay pier was dismantled and the remaining steamships were withdrawn at the same time. The line to Loch Tay remained in place as the engine shed and refuelling facility were used until the line closed. The Loch Tay section did enjoy a brief renaissance in 1950. A hydro-electric scheme was installed near to the site of the former Loch Tay station and the branch was heavily engaged in transporting the necessary materials to the development site.”

It is remarkable that the line, taken over a such a high cost by the LMS in 1923, was to provide its service to the village for a further 42 years in the face of improving roads and the rapid development of the motor vehicle. It’s fate was intimately tied to that of the line between Dunblane and Crianlarich Lower Railway Station. The closure of the main line was included in the ‘Beeching Plan’ published on 25th March 1963. Elton tells us that “The freight service between Killin Junction and the village station was withdrawn on 7th November 1964 in anticipation of the closure which was finally scheduled for 1st November 1965. It was perhaps an irony that an ‘Act of God’ preempted the plans of man. On 25th September 1965, an apparently minor rock fall occurred in Glen Ogle, blocking the ex-C&O main line. This resulted in the immediate cessation of all services on the route. On examination of the fall BR engineers found that it was of a much more serious nature than it had at first appeared. The estimated cost of repair was £30,000 and … was not considered a viable proposition.” [1: p632]

The last train on the Killin Branch ran on 27th September 1965. “The locomotive, BR 2-6-4T No.80093, gathered together the varied collection of rolling stock that had accumulated at the lower end of the line over the years. The massive locomotive needed two journeys from the village to Killin Junction to clear the stock, a motley collection consisting of three assorted passenger coaches and thirteen goods wagons. The conditions on the 1 in 50 climb out of the village were wet and greasy. Perhaps the miserable weather reflected the mood of the villagers on that now far-off day when they were deprived of the little railway that their forebears had fought so hard to win and retain over a period of 82 years.” [1: p632]

References

- Michael S. Elton; Killin Village Railway; in BackTrack Volume 14 No. 11, November 2000, p624-632.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killin_Railway, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- David Ross; The Caledonian: Scotland’s Imperial Railway: A History; Stenlake Publishing Limited, Catrine, 2014.

- John Thomas; The Callander and Oban Railway; David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1966.

- John Thomas and David Turnock; A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 15: North of Scotland; David & Charles (Publishers), Newton Abbot, 1989.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Killin_junction.jpg, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/82898787, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=881310860182217&set=gm.24913618418225514&idorvanity=1730959503584733, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://railwaycottagekillin.co.uk/history, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/irishswissernie/36765634322/in/album-72157688374962505, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/irishswissernie/36765633912/in/album-72157688374962505, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/irishswissernie/51151991311/in/album-72157688374962505, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/irishswissernie/36765633442/in/album-72157688374962505, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/irishswissernie/36765633072/in/album-72157688374962505, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/irishswissernie/50757614576/in/album-72157688374962505, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/irishswissernie/36765632732/in/album-72157688374962505, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/irishswissernie/49723182187/in/album-72157688374962505, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://www.rmweb.co.uk/forums/topic/138231-killin-junction-the-elusive-west-signal-box, accessed on 8th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=56.43045&lon=-4.37909&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.1&lat=56.43790&lon=-4.36066&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=0, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.1&lat=56.44083&lon=-4.35403&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/6159307, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=56.44675&lon=-4.34211&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.google.com/maps/place/Acharn+Biomass/@56.4467962,-4.3440616,3a,75y,90t/data=!3m8!1e2!3m6!1sCIABIhAA3ireqT2awWec7WgAC3RN!2e10!3e12!6shttps:%2F%2Flh3.googleusercontent.com%2Fgps-cs-s%2FAB5caB_gZBCcctUfajP9C1PShfXrShtzJLdwpeOsN5NnWscNVXPGY2yohixMrpVBrMPxuS4R73cqo6mMRfK1TwnVClw1p0sWpHcyK37Id4qABDCu1Fno_7CprFdmS0Qt-7gT_Sy4bao0jlst3bCH%3Dw203-h114-k-no!7i4032!8i2268!4m7!3m6!1s0x4888e90045545cf5:0xec8877ceb2ee340a!8m2!3d56.4473109!4d-4.3447361!10e5!16s%2Fg%2F11y5vmqg8c?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MDQwNi4wIKXMDSoJLDEwMjExNDUzSAFQAw%3D%3D#, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://electricityproduction.uk/plant/GBR2001109, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=18.0&lat=56.45294&lon=-4.33316&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acharn,_Perth_and_Kinross, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.lochlomond-trossachs.org/things-to-do/walking/short-moderate-walks/acharn-forest-killin/, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.onthemarket.com/details/13166199/#/photos/2, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://oban-line.info/an1.html, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=56.46066&lon=-4.32146&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=56.46291&lon=-4.31680&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.rmweb.co.uk/forums/topic/137795-modelling-the-co-the-callander-chronicles, accessed on 10th April 2025.

- This image was kindly shared with me by Ben Alder on 10th April 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/110691393@N07/36767993043, accessed on 10th April 2025.

- This image was kindly shared with me by Ben Alder on 10th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4241013, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- This image was kindly shared with me by Ben Alder on 10th April 2025.

- This image was kindly shared with me by Ben Alder on 10th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2249512, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- This image was kindly shared with me by Ben Alder on 10th April 2025.

- This image was kindly shared with me by Ben Alder on 10th April 2025.

- Andrew McRae; British Railways Camping Coach Holidays: A Tour of Britain in the 1950s and 1960s; Scenes from the Past: No. 30 (Part Two), Foxline, 1998.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1020015970165769&set=a.474445811389457, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4240479, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/880535, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5675070, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5675076, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5674957, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/880519, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5674963, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1570678, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/16Ekjwganr, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/915441, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/100064721257334/posts/pfbid037KHUnCzTUJJsdWAyqYk6obQTBd42NXUFGKMsB5WE9c1UfLNKPmWiUeD1Ch2Ttb1nl/?app=fbl, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/18i6up6DE3, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- https://www.ssplprints.com/products/pod1036094, accessed on 9th April 2025.

- J. N. Maskelyne; Real Railway Topics; in The Model Railway News, July 1938, p181-184.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=56.48079&lon=-4.30085&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 11th April 2025.

- This image was kindly shared with me by Ben Alder on 10th April 2025.

- This image was kindly shared with me by Ben Alder on 10th April 2025.

- This image was kindly shared with me by Ben Alder on 10th April 2025.

- This image was kindly shared with me by Ben Alder on 10th April 2025.

- https://popupdesigns.co.uk/products/killin-junction, accessed on 11th April 2025.

- https://popupdesigns.co.uk/products/killin-station, accessed on 11th April 2025.

- https://www.oban-line.info/kj2.html, accessed on 11th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=56.46690&lon=-4.31531&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=0, accessed on 11th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=56.47157&lon=-4.31514&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 11th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=56.47656&lon=-4.30934&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 11th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.7&lat=56.47881&lon=-4.30494&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 11th April 2025.