For Iranians, life changed dramatically in 1979.

It is easy, from a Western perspective, to assume that Iran became a country that has opted out of progress. Clearly, in late 1979 and the early 1980s there was a significant hiatus in the life of the country but this was temporary and as the 1980s progressed the economy began to improve and new railways became something of a touchstone by which to judge economic progress and growth.

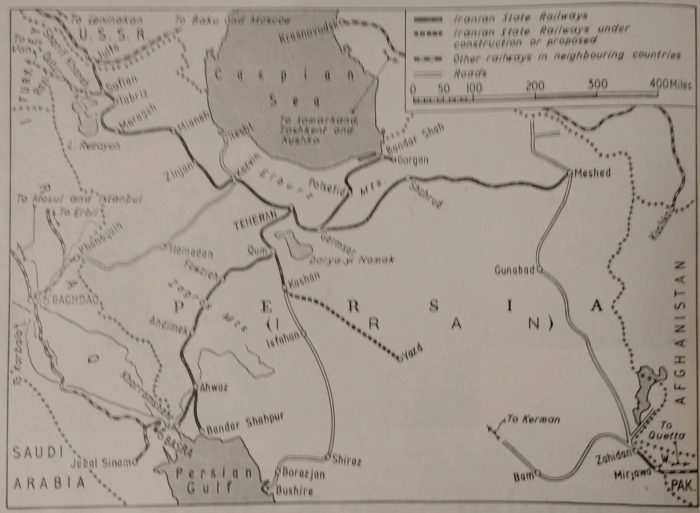

Wikipedia [5] highlights the long-distance schemes which were undertaken by the Islamic Republic of Iran Railways between 1979 and 1999, these include:

This table gives the locations linked by the length of railway constructed, the overall length in kilometres and the dates of construction work start and finish. Seven schemes were completed in this time period and three additional schemes were started and only completed after the millennium. [5]

Construction work was on a significant scale. The revolution may have resulted in a temporary halt to major construction work but the emphasis must be on the word ‘temporary’ as by 1982 major work on the line between Bafq and Bandar-Abbas was underway. The 626 km length of this line took 13 years to complete.

The long-distance major rail schemes tabulated above are:

Bafq — Bandar-Abbas: Bafq in Yazd Province, at the 2006 census,had a population of 30,867 in 7,919 families. [11] Bandar Abbas is a port city and capital of Hormozgān Province on the Persian Gulf in the South fo Iran. The city occupies a strategic position on the narrow Strait of Hormuz, and it is the location of the main base of the Iranian Navy. At the 2016 census, its population was 526,648. Bandar Abbas was a small fishing port of about 17,000 people in 1955, prior to initial plans to develop it as a major harbour. By 2001, it had grown into a major city. [12]

As we have already noted, this railway line extends for 626km and was built in the period from 1982 to 1995. Bafq is located on the Yazd to Kerman line. The line to Bandar Abbas branches off the older line to Kerman to the East the Railway Station, which is on the south side of the town..

Bafq Railway Station at a busy time (Google Earth).

This satellite image has picked up a train travelling from Bafq to Bandar-Abbas a few kilometres to the Southeast of Bafq (Google Earth). This is one of a signifcant number of trains which can easily be picked out on satellite images. The line, while being single track, is well-used.

Typical of the line as it passes through the Western part of Kerman Province and through Anar county close to the station at Bayaz. [14]

Ahmad Abad Railway Station

Sirjan Railway Station.

On leaving the Yazd Province, the line crosses Kerman Province, passing through stations such as Bayaz, Ahmad Abad, Khatunabad and Sirjan before entering Hormozgān Province,

On its way South the line served a number of different mineral and other concerns. Often providing a series of exchange sidings at the end of a branch-line. An example is shown on the landscape satellite image below the satellite image of Sirjan Railway Station.

The scenery in Hormozgān Province is much more mountainous and the railway passes through a myriad of relatively short tunnels on its way South.The line follows the River Rostam through the mountains, crossing it a number of times.

The exchange sidings shown below are just to the West of a large triangular junction which is shown on the following satellite image at a smaller scale.

At the triangular junction, one line heads almost due East for few kilometres to serve Bander- Abbas passenger station which appears on the satellite image below. The station sits on the North side of the city.

The other line heads South to the Hormozgan Steel Company and then on to the docks.

Bandar Abbas serves as a major shipping point, mostly for imports, and has a long history of trade with India, particularly the port of Surat. Thousands of tourists visit the city and nearby islands including Qeshm and Hormuz every year.

Bandar Abbas Railway Station (Google Earth).

The Hormozgan Steel Company (Google Earth).

The Hormozgan Steel Company in 2015 (c) Ali Nik (Google Maps) [15]

Wikipedia provides the table [5] above which shows construction of two further lines commencing in 1992 – a line from Bafq to Kashmar, and a line between Chadormalu and Meibod. Together, these two lines would have amounted to around 1020 km of railway.

Farrail, however, indicates that the line from Bafq to Kashmar and on to Mashhad was not started until 2001, and that the only line commenced in 1992 was that between Chadormalu and Meibod, this is verifiable from other sources as well. [22] [24]

Chadormalu to Meibod (Meybod)

Meybod Railway Station is on the line between Yazd and Qom. Meybod Railway Station is a few kilometres to the West of the city. In the 2006 census, Meybod had a population of 58,295, in 15,703 families. [6][23].

Meibod (Meybod) Railway Station (Google Earth).

The junction between the Qom-Yazd railway and that linking Meybod and Aghda is a few kilometres to the Northwest of Meybod (Google Earth) The point where the Maybod-Aghda line and the Qom-Aghda lines meet is just visible in the bottom right of the satellite image.

From the West, trains from Aghda line turn sharply away from the route to Yazd , turning through nearly 180° to head first due North towards Qom. For trains from the South, the route to Qom turns away North from the line to Aghda just north of Meybod Railway Station. Those two lines then converge as they head North, as shown in the satellite image below.

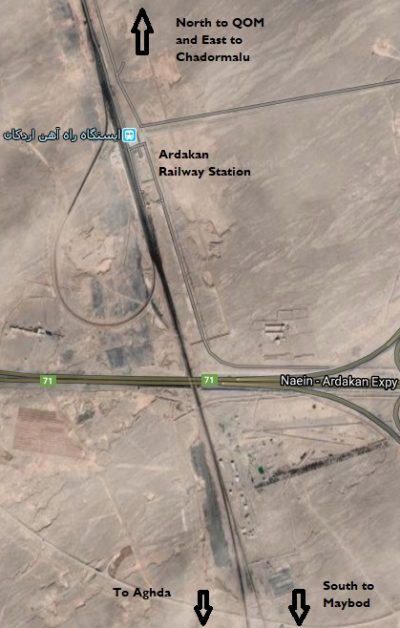

Just before passing under the modern Route 71, Naein to Ardakan Expressway and entering Ardakan Railway Station, the two lines finally join, as shown in the adjacent image.

Then to the North of Ardakan Railway Station the line to Qom and the line to Chadormalu diverge. The junction is literally at the top edge of the adjacent satellite image.

From Ardakan the line to Chadormalu turns Northeast and converges on the Qom-Chadormalu line. Once the two meet the railway continues heading Northeast for some distance. The first set of hills encountered diverts the railway first to the East and

then require it to loop its way through the topography and head off in a southeasterly direction as shown on the satellite image above. The line continues in this direction, passing under Route 68 and then turning East at a point which means that it avoids the next range of hills to the East. It passes to the South side of those hills and then continues and a predominantly Easterly direction to Chadormalu.

Wikipedia tells us that Chadormalu Iron Ore Mine and processing plant are situated in an otherwise uninhabited stretch of the Dasht-e Kavir desert about 180 km northeast of Yazd and 300 km south of Tabas, about 40 km off the Yazd – Tabas road. The ore deposits at Chadormalu were discovered in 1940 and construction of the mine complex began in 1994. Production was started in 1999. In the same year, the site was connected to the Iranian rail network near Meybod. [25]

An relatively short distance further to the East the line now joins the Bafq-Kashmar-Mashhad line which is described below.

Bafq to Mashhad via Kashmar – Despite its relatively small size, [11] Bafq has become a major junction on the Iranian rail network. Kashmar is in the Northeast of the country. It is in Razavi Khorasan Province and is located near the River Sish Taraz in the western part of the province, and 217 kilometres (135 miles) south of the province’s capital Mashhad. In the 2006 census, its population was 81,527, in 21,947 families. [6][16] The city is the fourth most important pilgrimage city in Iran. [17] It is a major producer of raisins and has about 40 types of grapes. It is also internationally recognized for exporting saffron, and handmade Persian rugs. [16]

Mashhad is the second-most-populous city in Iran and the capital of Khorasan-e Razavi Province. It had a population of 3,372,660 (in the 2016 census), which includes the areas of Mashhad Taman and Torqabeh. [3][4] It was a major oasis along the ancient Silk Road connecting with Merv to the East.

Wikipedia suggests that construction of this line started in the 1990s, [5] however, other, possibly more reliable, sources suggest otherwise. [1][2] This line has therefore been allocated to the subsequent article on Iran’s railways which deals with the period from the year 2000 onwards.

Mashhad to Sarakhs – this line runs from Mashhad [3] to Sarakhs was once a stopping point along the Silk Road, and in its 11th century heyday had many libraries. [7] Much of the original city site is now just across the border at Serakhs in Turkmenistan. According to the national census, in 2006, the city’s population was 33,571 in 8,066 families[6][8]

Southeast of Mashhad, a triangular junction sees the line South towards Kahmar and Bafq turning away to the Southwest and the line to Serakhs and Turkmenistan heading East. Almost immediately, trains travelling East enter Martyr Motahhari Railway Station shown on the satellite image below.

The line then travels in a predominantly Easterly direction, passing to the North of Razavieh and under the Mashhad to Sarakhs Road (Route 22) and following that road, on its North side until reaching Razavieh Railway Station and then climbs through the mountains. It continues to follow Route 22 for some way before striking off to the South-east of the road looking for the most suitable route through the topography a little to the Southwest of Mazdavand. The line tunnels under the two highest ridges in the mountain range as shown below, before winding back down under the Paskamar Road and onto more level ground.

By this time the railway is travelling in a North-northeasterly direction. It meets the Mashhad to Sarakhs Road (Route 22) once again just a kilometre or two before running into Sarakhs Railway Station. The line runs Southwest to Northeast across the satellite image below. The Railway Station is in the centre of the image.

Sarakhs Railway Station sits between two large marshalling yards (Google Maps).

Just beyond Sarakhs the line crosses the border into Turkmenistan and continues to cross the Garagumskij (Karakum) Canal in that country. [9][10]

Aprin to Maleki – This line was built in the period from 1993 to 1997 and was the first part of a longer line which linked Maleki to Mohammediya via Aprin. Aprin is in the Southwestern suburbs of Tehran. The satellite image below shows the town boundaries as a red line with a railway sitting just to the North. There is seemingly little to suggest why this became an important line until we begin to look at what has been happening since the relaxation of sanctions in 2015. Aprin is to be a significant transport hub and will be developed over a number of years. International contractors and rail companies have become involved in what is a major infrastructure development in the 21st century.

Called Aprin Dry Port, the facility will connect Iran’s port cities to the centre of the country in Tehran and will act as Iran’s central cargo train intersection, The contract for the work was signed in September 2016. It is a 25 years contract which will receive an investment of $30 million for its first phase, which will take 2.5 years to become operational. Plans were made for this development in the late 1970s but are only coming to fruition in the early 21st century. [11][14]

Trains will be able to load containers directly from ships at Persian Gulf ports and carry them to Aprin in 60 hours. Clearance procedures will be undertaken at Aprin. The contractor has guaranteed a minimum load traffic of 400,000 TEU (Twenty-Foot Equivalent Unit) through the port. The railways company is also planning to develop a double-stack rail transport system from Bandar Abbas (port city by the Persian Gulf) to Aprin in two years. [11][14]

The dry port is especially significant since it is being developed at the same time as the North-South Corridor is under construction. The international corridor will take cargos from India on board ships to Iran, and from there to Azerbaijan, Moscow, and eventually Europe. [11][14]

Looking at a wider area around Aprin on Google Earth shows a very significant concentration of rail lines in the immediate vicinity of Aprin, the satellite image immediately below shows these lines.

The rail network in the immediate vicinity of Aprin (Google Maps).

The line leaving the satellite image above on the top right runs across Tehran to link with the main line. just to the west of Tehran Railway Station. There are a number of loactaios in Tehran which are marked as ‘Maleki’ on Google Maps, one is just to the East of Tehran Railway Station a little to the North of the locomotive depot. I cannot be sure of the location of the Maleki referred to in the Wikipedia article. [5] The name is, however, used consistently in other sources, [eg. 25]

The line leaving the Satellite image of Aprin above in the bottom left runs to Mohammediya and beyond. It crosses an open plain with no significant features.

Mohammediya Railway Station (Google Maps)

Mohammediya Railway Station in 2017(Google Maps)

It is of particular interest that the line form Maleki through to Mohammediya via Aprin was built between 1993 and 1999 as it indicates that the proposed dry port in Aprin was in the minds of the Iranian regime in the 1990s. It is now part of modern Iranian plans for six such dry ports country-wide. [28][29]

A dry port is a terminal situated in an inland area with rail connections to one or more container seaports. A container freight train service runs between the seaports and the dry port, on a service timetable that is integrated with the schedules of the container ships arriving at the seaport. [28][30]

Badrud to Meibod (Meybod) – Badrud is in Isfahan Province. At the 2006 census, its population was 14,391, in 3,709 families. [27]. The line from Meybod was constructed between 1996 and 1998. Its railway station is to the South-southeast of the town as can be seen on the Satellite image below.

Bad (Badrud) and its Railway Station (Google Maps).

Badrud Railway Station (Google Maps).

The Railway Station is just to the West of a railway junction, as can be seen above. The route South heads up into the nearby hills, through Espidan Railway Station and on to join the railway to the East of Sejzi Railway Station, below.

Sejzi Railway Station (Google Maps)

The line heading Southeast from Badrud, travels through Zavareh and Naein Railway Stations before leaving Istafan Provence and entering Yazd Province and reaching Meybod. The line predominantly runs in a Southeast to South-southeast direction over its full length.

Mohammediya-2 — Mohammediya-1 – this is a very short stretch of line which was built between 1994 and 1999. The six kilometres involved took 5 years to complete. Mohammediya appears to sit very close to QOm – just to its Southeast and the line from Aprin appears to make a 90 degree junction with the Main line just to the South of QOM. I have been unable to identify the position of a second location within 6km of distance of Mohammediya Station, although it is less than 10km from the main line. Other sources [eg. 25] do not separate the construction of the railway in this location into separate parts, seemingly including this section in with the whole line from Aprin to Mohammediya.

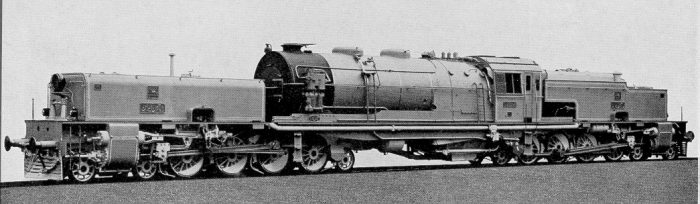

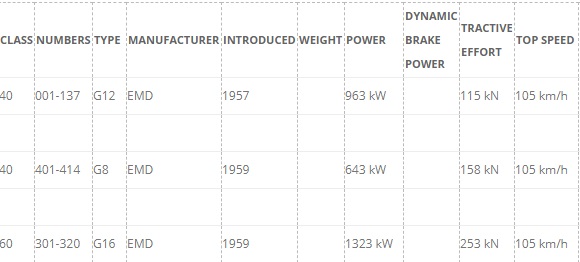

Locomotives purchased during this period included:

1982: 20 No. G22W Diesel-Electric Locos numbered 40.159 to 40.178 built under GM licence by Duro Dakovic in what was then Yugoslavia. [31]

1982: 8 No. ASEA (Allmänna Svenska Elektriska Aktiebolaget) Bo-Bo Electric Locos numbered 40.651 to 40.658. These were purchased for use on the Tabriz-Jolfa line. [32]

1984: 60 No. GMD GT26CW Co-Co Diesel Electric Locos numbered 60.915 – 60.974.

1985-1986: 10 Hyundai GT26CW Co-Co Diesel Electric Locos numbered 60.975 – 60.984.

1985-1986: 10 Hyundai GT26CW-2 Co-Co Diesel Electric Locos numbered 60.985 – 60.994.

1986: 10 No. Electroputere LDE2630 Co-Co Diesel Electric Locos numbered 60.351 – 60.360.

1986: 10 No. Electroputere LDE2100 Co-Co Diesel Electric Locos numbered 60.701 – 60.710. These Locos where first in service on Romanian State Railways (CFR)

1992: 21 No. General Electric U30C Co-Co Diesel Electric Locos numbered 60.2001 – 60.2021.

1993: 34 No. General Electric Montreal C30-7i Co-Co Diesel Electric Locos numbered 60.2022 – 60.2055.

1994: 7 No. General Electric C30-7i Co-Co Diesel Electric Locos numbered 60.2056 – 60.2062.

1997: 12 No. Zhuzhou TM1 Bo-Bo Electric Locos numbered TM1-001 to TM1-012. These were purchased for use on the Tehran-Karaj Metro. [32]

1999/2000: 20 No. GEC-Alstom AD43C Diesel Electric Locos numbered 60.201 – 60.220.

1999/2000: 10 No. Wagon-Pars AD43C Diesel Electric Locos numbered 60.221 – 60.230.

A further 70 No. Wagon-Pars AD43C Diesel Electric Locos were purchased between 1999/2000 and 2003 and numbered 60.231 – 60.300.

Please note that GMD above is General Motors Diesel, London, Ontario, Canada. Hyundai (Korean) build GM locos under licence.

My thanks to Martin Baumann for help in confirming this list of locomotives.

References

- https://www.farrail.com/pages/touren-engl/Railways-in-Iran-2016.php, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- M. Frybourg et B. Seiler; Globe Trotter : Des trains en Iran; Objectif Rail n°77 September/October 2016, p 68-85.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mashhad, accessed on 6th April 2020.

- “Razavi Khorasan (Iran): Counties & Cities – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts”. http://www.citypopulation.de/php/iran-khorasanerazavi.php, accessed on 6th April 2020, and quoted by Wikipedia in reference [3] above.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_Republic_of_Iran_Railways, accessed on 29th March 2020.

- Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1385 (2006); Islamic Republic of Iran. Archived from the original (Excel) on 11th November 2011 and quoted by Wikipedia in references 8, 11, 12 and 16 below.

- Sarakhs city in Khorasan Razavi province; Travel to Iran, Visit Iran; Iran Tourism & Touring. The website is itto.org which was created by http://www.sirang.com, Sirang Rasaneh, accessed on 10th April 2020 and quoted in reference [8] below.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarakhs, accessed on 10th April 2020.

- https://www.railwaygazette.com/news/infrastructure/single-view/view/iran-inaugurates-railway-to-border-with-turkmenistan.html, accessed on 6th April 2020 and quoted in reference [5] above.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karakum_Canal, accessed on 10th April 2020.

- https://www.wroseco.com/index.php?m=news&a=card&id=95&name=ground-shipping-rolling-towards-prosperity-for-tehran-and-beyond, accessed on 10th April 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bafq, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bandar_Abbas, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- https://ptbgroup.biz/Group/Aprin-Perse, accessed on 10th April 2020.

- https://rail-news.ir/خروج-چند-واگن-باری-در-بلاک-اضطراری-بیاض, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- https://goo.gl/maps/mTpsZ1MPsVzBqxRt6, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kashmar, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- khorasan.iqna.ir, quoted in reference 16 above and noted on 4th April 2020. This article is not written in English and will need translation software it it is to be read in English.

- https://www.waze.com/en-GB/livemap, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- https://www.google.co.uk/maps/place/Choghart+Iron+Mine/@31.7003018,55.4698463,3a,75y/data=!3m8!1e2!3m6!1sAF1QipPYLmKr21Z-kKbP9-liOIvQOc7bUKvobIJgUXTI!2e10!3e12!6shttps:%2F%2Flh5.googleusercontent.com%2Fp%2FAF1QipPYLmKr21Z-kKbP9-liOIvQOc7bUKvobIJgUXTI%3Dw114-h86-k-no!7i4128!8i3096!4m13!1m7!3m6!1s0x3fa82f568572170b:0x5a1d010a9aa87c!2sBafgh,+Yazd+Province,+Iran!3b1!8m2!3d31.6216425!4d55.4139392!3m4!1s0x3fa8273801690549:0x2c64d562f8ad363!8m2!3d31.700303!4d55.4698473#, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- https://www.google.co.uk/maps/place/Choghart+Iron+Mine/@31.700303,55.4698473,3a,75y,90t/data=!3m8!1e2!3m6!1sAF1QipPMm5u7jHg1feIHONAM9Xhl8ashkIa1GQkO8Yly!2e10!3e12!6shttps:%2F%2Flh5.googleusercontent.com%2Fp%2FAF1QipPMm5u7jHg1feIHONAM9Xhl8ashkIa1GQkO8Yly%3Dw203-h123-k-no!7i1200!8i733!4m13!1m7!3m6!1s0x3fa82f568572170b:0x5a1d010a9aa87c!2sBafgh,+Yazd+Province,+Iran!3b1!8m2!3d31.6216425!4d55.4139392!3m4!1s0x3fa8273801690549:0x2c64d562f8ad363!8m2!3d31.700303!4d55.4698473#, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- https://www.google.co.uk/maps/place/Neygenan/@34.302021,57.3525574,3a,75y/data=!3m8!1e2!3m6!1sAF1QipPgRSnb3niAHFzEvByGD8Qa2mGGOACPzLm0Wjgs!2e10!3e12!6shttps:%2F%2Flh5.googleusercontent.com%2Fp%2FAF1QipPgRSnb3niAHFzEvByGD8Qa2mGGOACPzLm0Wjgs%3Dw86-h114-k-no!7i1536!8i2048!4m5!3m4!1s0x3f0c40c3cad3fc83:0x4d2189b4cc1fa01!8m2!3d34.3020213!4d57.3524952#, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- https://www.farrail.com/pages/touren-engl/Railways-in-Iran-2016.php, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meybod, accessed on 4th April 2020.

- M. Frybourg et B. Seiler; Globe Trotter : Des trains en Iran; Objectif Rail n°77 September/October 2016, p 68-85.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chadormalu, accessed on 10th April 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Badrud, accessed on 13th April 2020.

- https://financialtribune.com/articles/economy-domestic-economy/66209/iran-plans-to-establish-six-dry-ports, accessed on 13th April 2020.

- https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/Iran-DP-WGM-1.pdf, accessed on 13th April 2020.

- https://www.academia.edu/8540005/Feasibility_of_establishment_of_Dry_Ports_in_the_developing_countries_the_case_of_Iran, accessed on 13th April 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EMD_G22_Series, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Railway_electrification_in_Iran, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2016-05-11_Iranian_Railways_EMD_G22W_Bo-Bo.jpg, accessed on 15th August 2023.

- https://bahnbilder.ch/picture/5787, accessed on 15th August 2023.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Electroputere_locomotives#/media/File:26.09.12_Karnobat_46234_(8047699822).jpg, accessed on 15th August 2023.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GE_U30C, accessed on 15th August 2023.

- https://www.mainlinediesels.net/index.php?nav=1000909&lang=en, accessed on 15th August 2023.