In June 1990, The Railway Magazine issued a supplement entitled ‘King’s Cross Renaissance: The History, Development and Future of Two Great Stations’ by P. W. B. Semmens MA, CChem, FRSC, MBCS, MCIT.

Semmens introduces the supplement by highlighting first the 1846 ‘Royal Commission on Railway Termini Within or in the Immediate Vicinity of the Metropolis’ which recommended that “surface railways should remain towards the outskirts, and fixed a ring of roads around the city, beyond which they should not penetrate.” [1: p3]

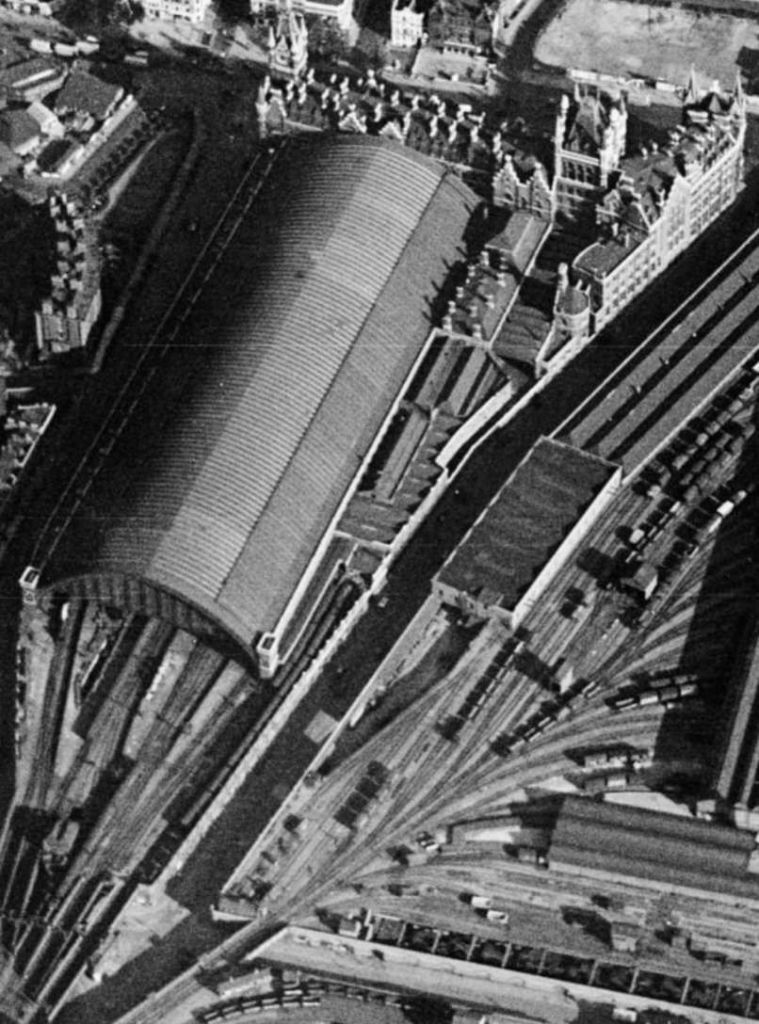

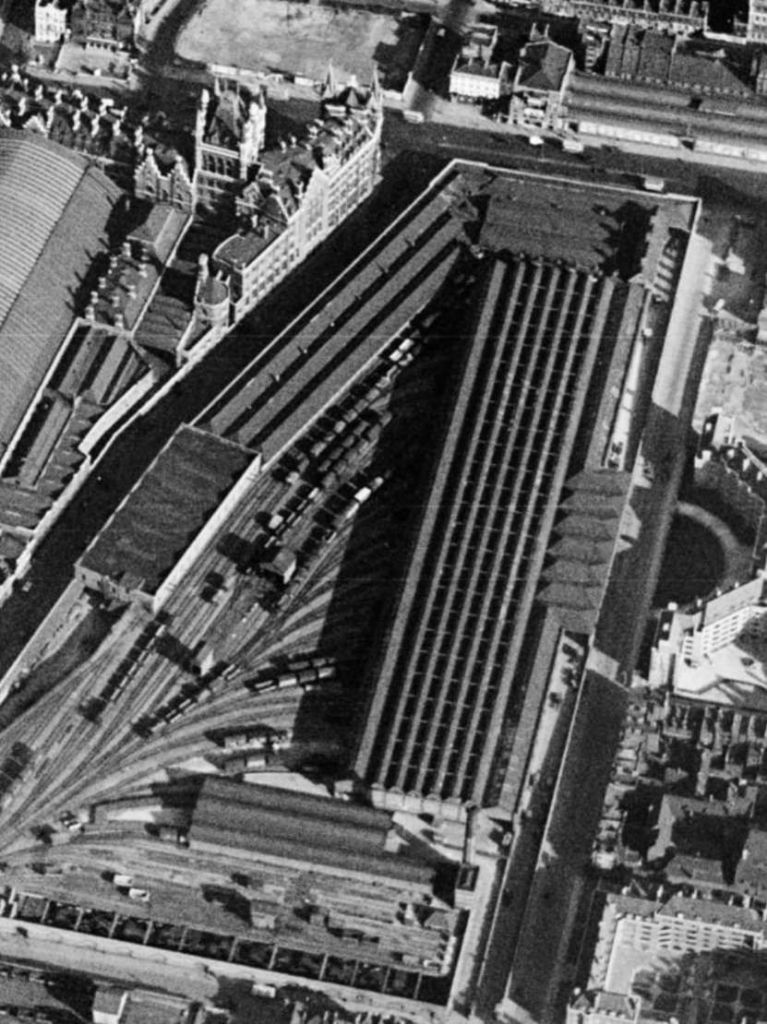

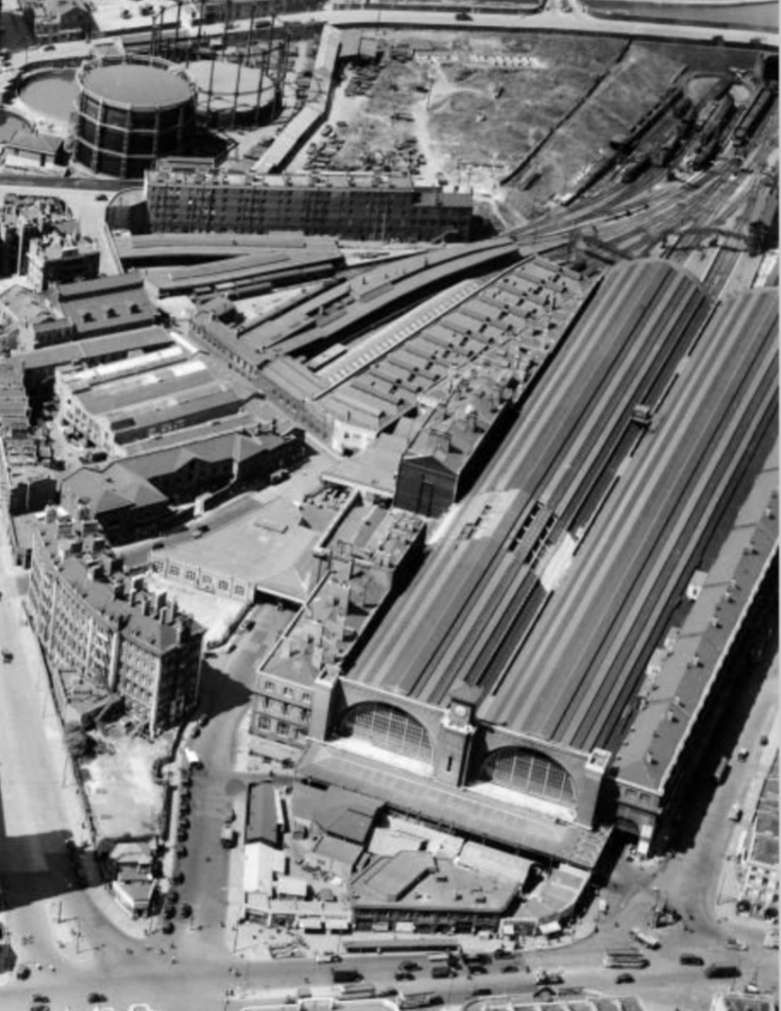

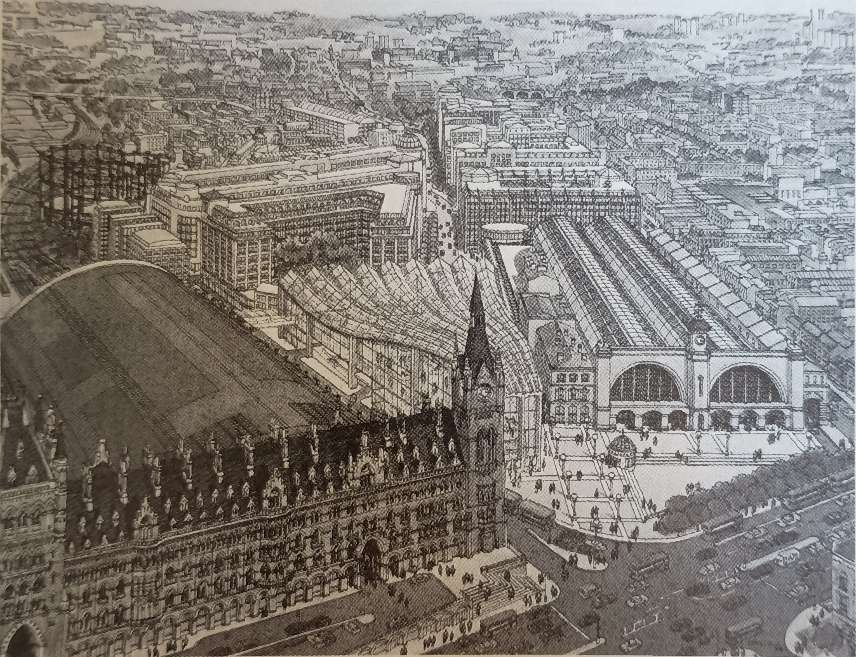

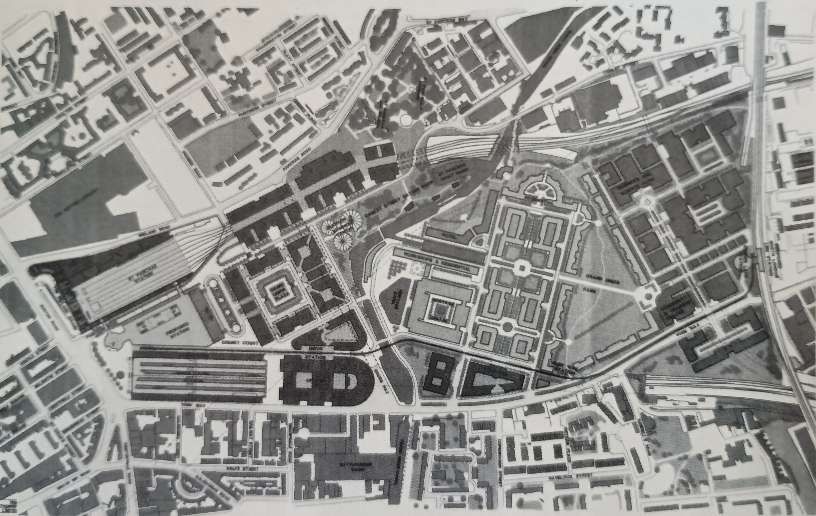

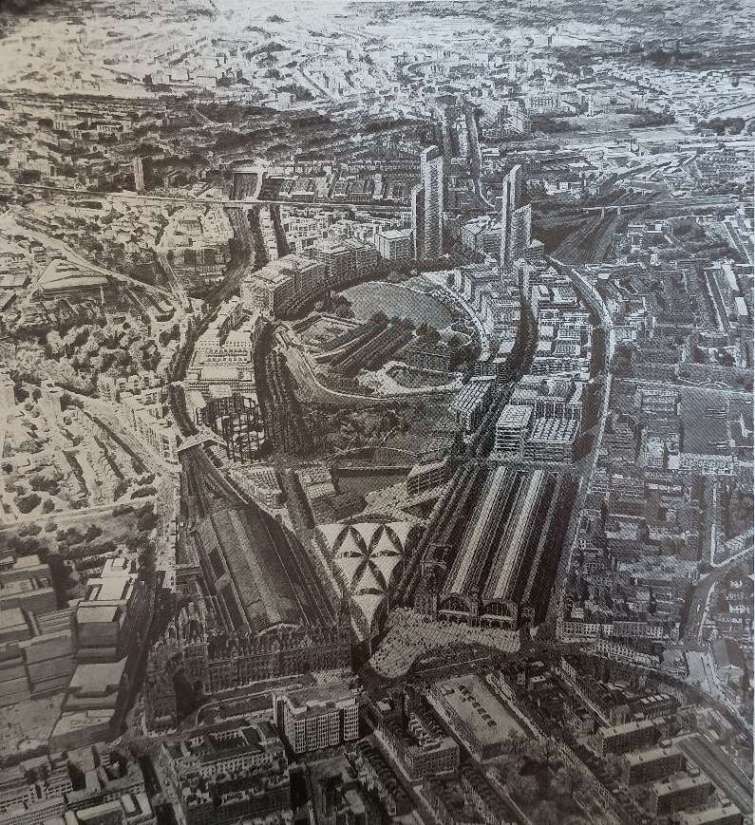

The next few images show these buildings from the air. …

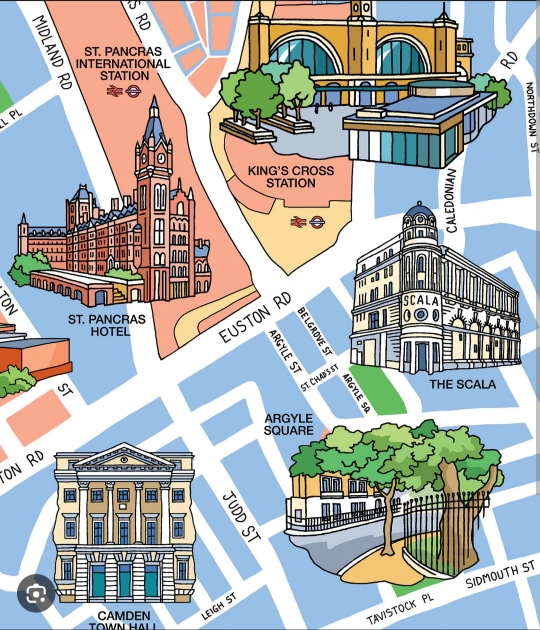

By 1990, the main line railway still barely penetrated the central core of London “and only Thameslink crossed the built up area to provide a through route.” [1: p3] The impact of the Royal Commission was most obvious “in the North of the city, where five of our main line termini … situated in a virtually straight line along one major road, stretching from Paddington in the West to the twin stations of St. Pancras and King’s Cross five miles away to the East.” [1: p3] As a result passengers heading into the centre of London still have to change to other forms of transport even if limited subsurface onwards extensions were provided by three of the termini.

In the latter half of the 20th century, developments in service industries and improved electronic communication systems have allowed companies, which originally needed to be closely situated in the centre of the city, to look for alternative, better locations. “The railway termini, with their built-in transport facilities for staff, thus provide excellent sites at which to build new offices, and BR [was] extensively involved in many such developments, after its initial office plans for the new Euston had been thwarted by the government of the day. Some of the London termini, however, are of such outstanding architectural merit that it is not acceptable for them to be swept away and replaced by office blocks on top of improved station facilities for trains and customers. Notable among these are St. Pancras and King’s Cross, both Grade I listed buildings, whose proximity to each other makes them unique in London. (Broad Street was never really a main-line terminus, as its services were virtually all of a suburban nature.)” [1: p3]

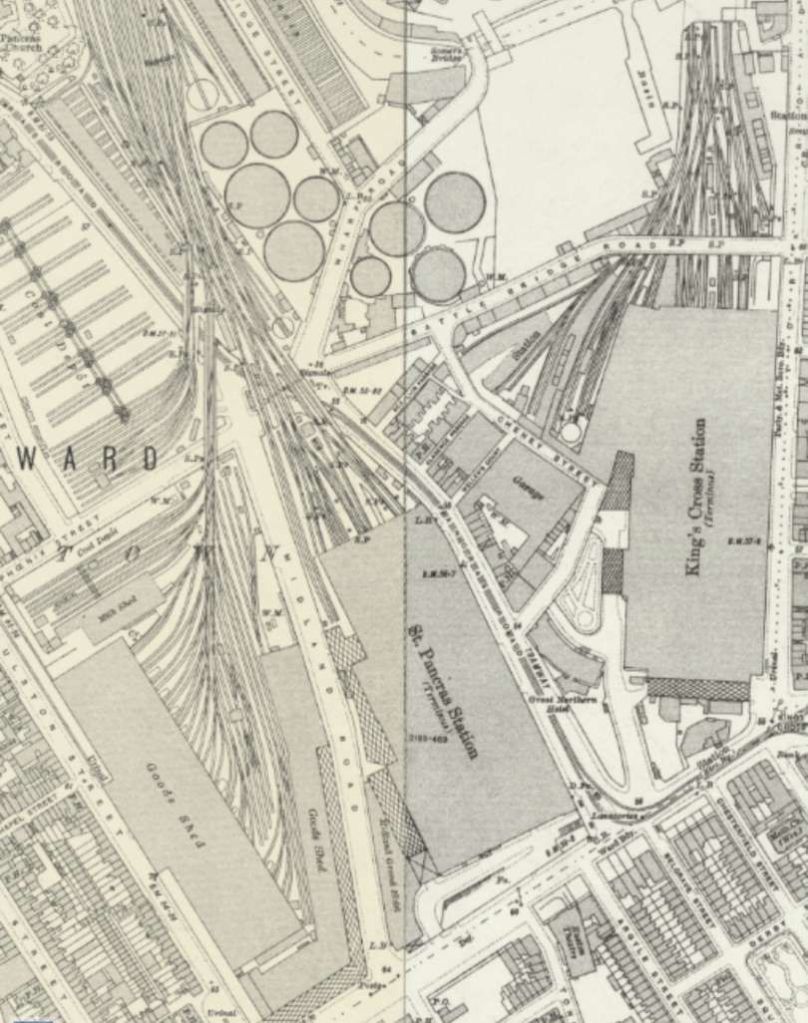

In addition, “Extensive goods activities were also developed by the railways close to many of their London main-line termini. This was particularly apparent in the vicinity of King’s Cross and St. Pancras, where there were vast areas devoted to the vital job of keeping the country’s capital provisioned, fuelled, and even ‘mucked out’, as arrangements had to be made for the removal of refuse by rail.” [1: p3]

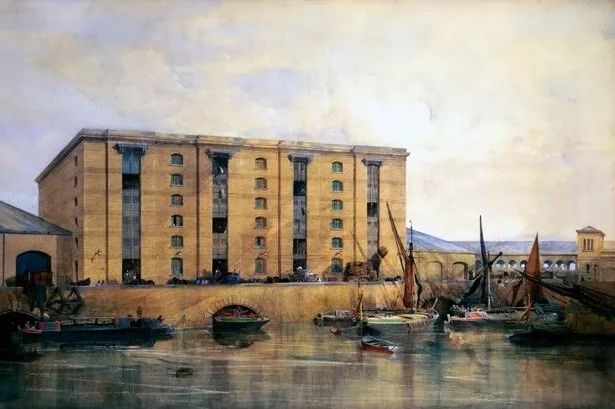

The Great Northern Railway’s “Goods Yard complex, designed by Lewis Cubitt, was completed in 1852. The complex comprised the Granary Building, the Train Assembly Shed, and the Eastern and Western Transit Sheds. The buildings were aligned to the axis of the Copenhagen tunnel through which the trains arrived from the north. … The Granary building was mainly used to store Lincolnshire wheat for London’s bakers, while the sheds were used to transfer freight from or to the rail carts. Off-loading from the rail carriages was made easier by cranes and turntables powered by horses and, from the 1840s, hydraulic power. … Loaded and unloaded carts were moved into the Train Assembly Shed and formed into trains for departure northwards. Stables were located under the loading platforms – some of these remain in the Western Transit Shed. … In the 1860s, offices were added on either side of the Granary to provide more clerical workspace. Dumb waiters were used to transport papers up and down and windows between the offices and sheds allowed traffic to be monitored.” [6]

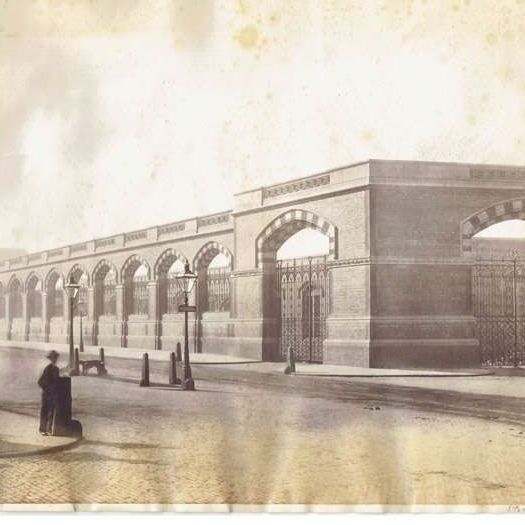

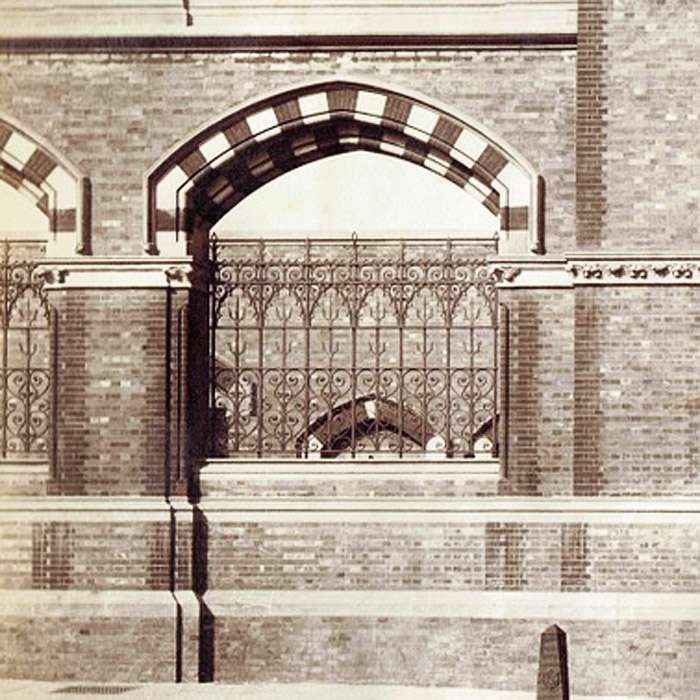

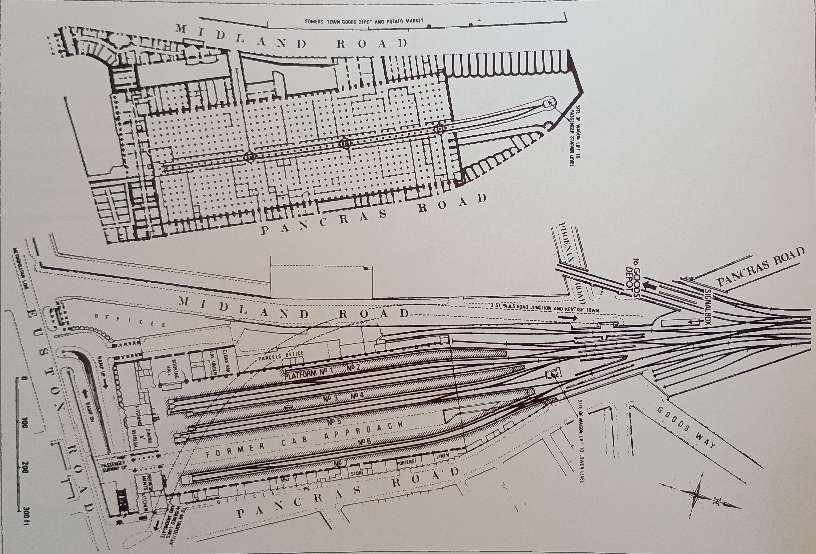

The Midland Railway’s Somers Town Depot sat adjacent to St. Pancras Station on the West side of Midland Road. The next two images give an idea of the detailed brickwork used on the boundary walls of the depot.

Somers Town Depot was an ambitious two-deck goods yard that differed from neighbouring King’s Cross to the east in that the tracks and platforms were raised. “This enabled the tracks to traverse above the Regents Canal to the north and arrive at their terminus before the Euston Road at that high level (conversely, the Great Northern Railway tracks to Kings Cross passenger station tunnelled underneath the canal and stayed low). Beneath, loading bays were envisioned – a logistics hub for triage, trade and distribution on to the horse-drawn road network. With its own independent hydraulic system, 20ton loaded railway wagons could be dropped to the lower level on lifts for unloading.” [12]

The technical design was accompanied by carefully developed aesthetical design work in order to – to compliment Sir George Gilbert Scott’s passenger terminus next door. “A vast decorative screen wall would contain and secure the goods depot – necessarily tall to both encompass the raised sidings within, and the perimeter access roadway around them, but essentially horizontal in format – emphasising the soaring vertical spires of The Midland Grand Hotel beyond.” [12]

The screen wall was 3250 feet or about three-quarters of a mile in length, 30 feet high and nearly 3 feet thick and surrounded the whole site. It required “about 8,000,000 bricks of a peculiarly small size, rising only 11 inches in four courses, which greatly improved the appearance of the work. It [was] faced with Leicestershire red brick, the inner portion being entirely of Staffordshire blue bricks, set in cement, no lime having been used in this or any other work on the depot. … The elevation on the Euston Road [was] tastefully ornamented with Mansfield stone, whilst the large arched openings, left in the wall to assist in lighting the roadway which runs around the enclosure, [were] protected by hammered iron screens, 11 feet by 8 feet, and weighing about 12 cwt. Each, of beautiful workmanship.” [12][13]

“While the Midland [Railway] developed some of its goods facilities alongside the passenger station, the Great Northern [Railway] adopted a different strategy. Its corresponding activities were carried out to the north of King’s Cross terminus, in an area lying mainly to the west of the main lines, although some of them were actually situated above the tracks through Gas Works Tunnel. Much of this land [in 1990] is now derelict or only partially used, and the idea of making use of it has been carefully studied during recent years. The first intention was just to make better use of the area for housing, offices and leisure, but the upsurge in rail travel during the last few years, plus the building of the Channel Tunnel, has provided the incentive to include additional and better facilities for those who travel to and from the two main-line stations by train.” [1: p3]

However, the major switch from rail to road transport in the later half of the 20th century saw a steady decline in the need for such significant goods handling facilities. And as the end of the century approached these areas were repurposed to help regenerate inner city areas and improve transport infrastructure.

Writing in 1990, Semmens tells us that “A large proportion of the Midland’s goods activities used to be carried out in its Somers Town Depot, situated immediately to the west of the passenger station, on the other side of Midland Road. The need for this from the railway’s operational point of view ceased many years ago, and after the site had been cleared, it was used for the new British Library. After years of work, which started at a great depth below street level, the £450 million building is now well on the way to completion. It is expected to be fully in use by 1996, although the first public access to the new facilities will be three years earlier.” [1: p3]

The British Library was created on 1st July 1973 as a result of the British Library Act 1972. [7] Prior to this, the national library was part of the British Museum, which provided the bulk of the holdings of the new library, alongside smaller organisations which were folded in (such as the National Central Library,[13] the National Lending Library for Science and Technology and the British National Bibliography). [7]. In 1974 functions previously exercised by the Office for Scientific and Technical Information were taken over; in 1982 the India Office Library and Records and the HMSO Binderies became British Library responsibilities. In 1983, the Library absorbed the National Sound Archive, which holds many sound and video recordings, with over a million discs and thousands of tapes. [8]

For many years the British Library’s collections were dispersed in various buildings around central London, in places such as Bloomsbury (within the British Museum), Chancery Lane, Bayswater, and Holborn, with an interlibrary lending centre at Boston Spa, 2.5 miles (4 km) east of Wetherby in West Yorkshire (situated on Thorp Arch Trading Estate), and the newspaper library at Colindale, north-west London. [7][8]

The St Pancras building was officially opened by Her Majesty the Queen on 25th June 1998. [10]

Library stock began to be moved into the new building on 25th October 1997 By the end of 1997, the first of eleven new reading rooms had opened and the moving of stock was continuing. [8] The library continued to expand, from 1997 to 2009 the main collection was housed in the new building and the collection of British and overseas newspapers was housed at Colindale. In July 2008 the Library announced that it would be moving low-use items to a new storage facility in Boston Spa in Yorkshire and that it planned to close the newspaper library at Colindale, ahead of a later move to a similar facility on the same site. [9] From January 2009 to April 2012 over 200 km of material was moved to the Additional Storage Building and is now delivered to British Library Reading Rooms in London on request by a daily shuttle service. Construction work on the Additional Storage Building was completed in 2013 and the newspaper library at Colindale closed on 8th November 2013. The collection has now been split between the St Pancras and Boston Spa sites. The Library previously had a book storage depot in Woolwich, south-east London, which is no longer in use. [8]

But, in looking at the British Library in the 21st century, we are getting ahead of ourselves! …

1: Two Great Stations and their Goods and Locomotive facilities

A: King’s Cross Station to 1990

The earliest of the two stations was the Great Northern Railway’s King’s Cross. It was shared with the Midland Railway for 20 years while St. Pancras Station was being built. The building which appears on the aerial images near the head of this article was completed in 1852. It was preceded by a temporary GNR building situated between Copenhagen Tunnel and Gas Works Tunnel.

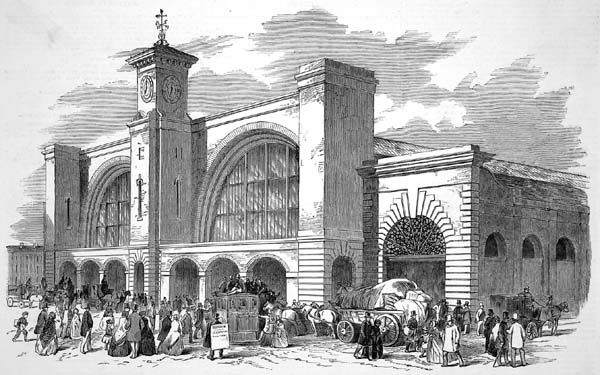

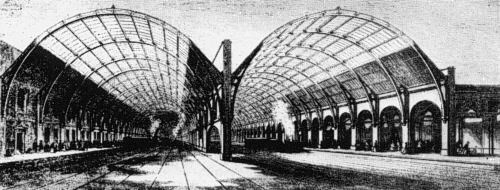

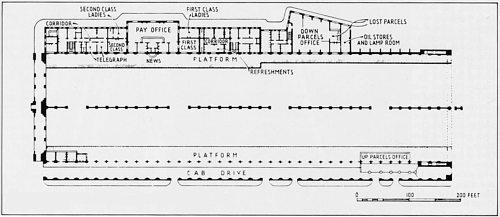

Semmens tells us that “The 1852 station was a striking building, designed by Lewis Cubitt, with twin train-sheds linked at the South end by a brick façade. It was surmounted by a tower in Italianate style, complete with a clock, which had been on show at the Great Exhibition, and a bell. When built it was the largest station in Britain, and this moved certain shareholders to complain of extravagance. The building was, however, a fairly simple one, with only two platforms being provided originally, one for arrivals and the other for departures, set against the two outer walls. Between them were no fewer than 14 carriage roads, inter-connected by turntables and cross-tracks, as the four-wheeled vehicles of those days were small enough to be shunted like this, even by manpower, from one place to another within the confines of the station.” [1: p4]

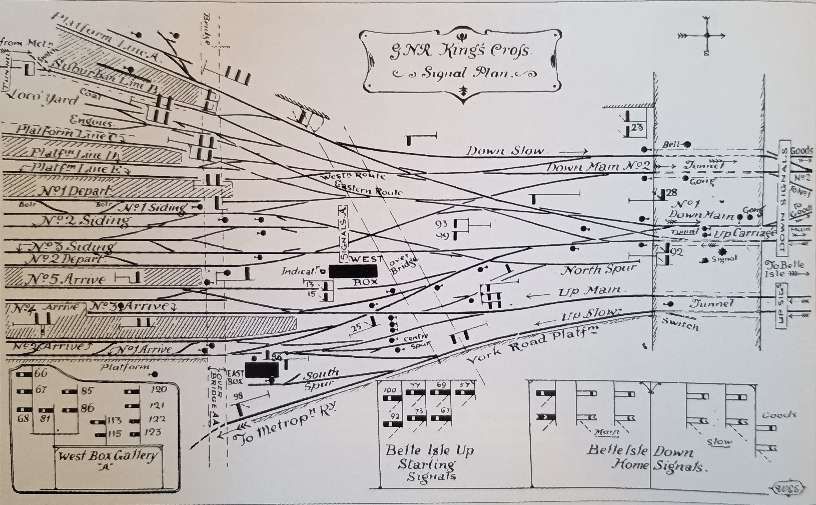

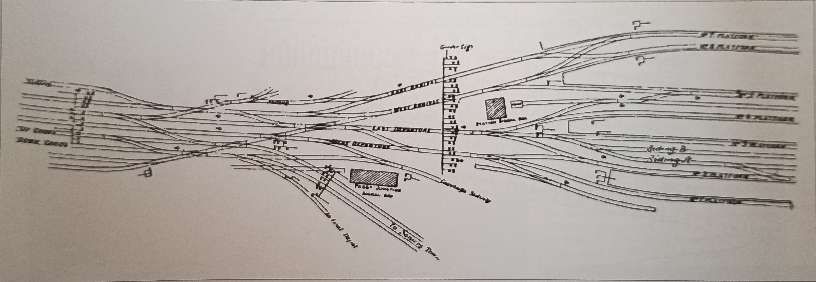

Semmens continues: “Many changes took place during the station’s first half-century of operation, and its layout had altered considerably by 1905, when it featured in a series on signalling in The Railway Magazine.” [1: p4]

The Great Northern Railway opened its connection to the Inner Circle of the Metropolitan Line in 1863. In 1865, the York Road Platform was constructed to allow trains bound for the City to stop before heading into the tunnel which took them down to the Inner Circle. “Northbound trains were not provided with a similar platform on the down side until 1878, even though what was to become the semi-detached Suburban station had come into use three years earlier. The use of these curves at King’s Cross was considerably extended after 1866 when the Snow Hill connection was completed between Farringdon and Holborn Viaduct, as it became possible to run through trains from the Great Northern to destinations south of the Thames. Considerable amounts of freight were also worked this way, and the provision of a banker to help loose-coupled trains up the steep incline from Farringdon lasted until after nationalisation. The passenger trains, however, were withdrawn before the first world war, as travellers had opted to use the better connections then being provided by the Underground.” [1: p5]

Semmens notes that, “Gradients on Hotel Curve, as the line up from the Metropolitan was called, were as steep as I in 35, and the station stop at the top caused endless difficulties with the operation of these through services.” [1: p5]

He continues, “It will be seen from the 1905 diagram that at that time there was a small locomotive yard, complete with turntable, between the suburban and main-line stations. In 1923 this was moved to its better-known position on the west side of the lines where they entered Gas Works Tunnel. The railway had purchased some of the land formerly used by this utility, and installed a 70ft turntable there to cope with the new Pacifics which were starting to emerge from Doncaster. Although the main locomotive activities at King’s Cross were centred on Top Shed, situated further to the north in the middle of the Goods Yard, there were obvious advantages in providing facilities closer at hand for turning and refuelling incoming locomo-tives before they took up their return workings. The end of the main departure platform (for many years No. 10, but now No.8) provided generations of enthusiasts with a grandstand view of these activities, which continued through the diesel era until the East Coast workings became monopolised by the HSTs.” [1: p5-6]

As well as a cramped layout and the proximity of the tunnels to the station throat, there were two overbridges. One served the Gas Works and was removed in 1912, the other was removed in 1921 when an alternative access route, ‘Goods Way’ was built South of Regents Canal over the mouth of the tunnels. Sightlines from the signal cabins were poor. As a result rudimentary track circuits were installed as early as 1894. [1: p6]

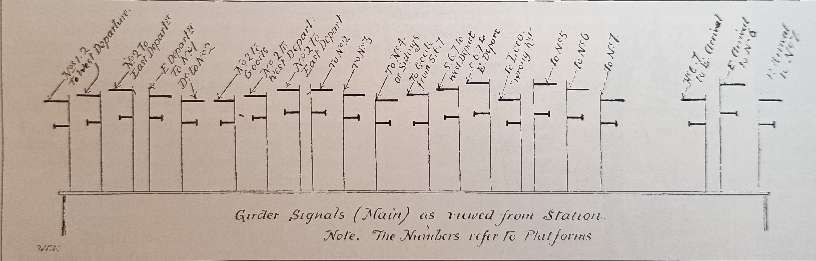

Semmens reported in 1990 that, “Since 1905 there [had] been three major changes in the signalling for the King’s Cross area. The first took place just before the Grouping, when a number of three-position upper-quadrant semaphores were installed, with roller-blind route indicators. In 1932 there was a much bigger change in the station area, with colour lights replacing the semaphores, and the points being worked electrically. The distinctive roller-blind route indicators were to remain until 1977, which saw the commissioning of the modern power box, situated on the up side immediately south of Gas Works Tunnel, While the previous all-electric box had just controlled the approach lines and those in the station itself, the present panel interface[d] with the Peterborough one at Sandy, 44 miles away. For good measure it also control[ed] the Hitchin-Cambridge line as far as Royston. … This latest change was part of two major developments on the East Coast Main Line in the 1970s, the Great Northern suburban electrification and the introduction of the Intercity 125s. The first of these resulted in an appreciable reduction of movements in the terminus, as the inner suburban services, worked by the dual-voltage class 313 units, were mainly diverted from Finsbury Park to Moorgate through the large-bore tunnels which were built in 1904 as the Great Northern & City Railway. From this there is now an excellent cross-platform interchange at Highbury & Islington with London Transport’s Victoria Line, giving frequent connections to and from King’s Cross Underground. They supplement those at Finsbury Park off the outer-area EMUs operating from King’s Cross suburban station, which has recently had a fourth platform added. Under the refurbished roofs of the train-sheds there [was] a straight-forward eight-platform layout for main-line trains, but the connections to the Inner Circle [were] severed, as the new inner-suburban trains now reach[ed] the City directly from Finsbury Park.” [1: p7]

Semmens also comments: “As part of this electrification scheme, the old freight flyover north of Copenhagen Tunnel was rebuilt to take passenger trains, and rails were removed from the most easterly bores of Gas Works and Copenhagen Tunnels. All this resulted in a much simpler layout at King’s Cross, and it was possible to improve the speed restrictions, which increased the station’s capacity, as well as reducing journey times. The 25 kV overhead catenary was put up [and] provide[d] power for the electric Intercity services which [were] already running as far as Leeds and York, and [would] be extended to Edinburgh and Glasgow in May 1991. … At the opposite end of the station, a considerable improvement in the passenger amenities was introduced in the early 1970s. When King’s Cross was built, the south end of the train sheds lay alongside St. Pancras Old Road, but the changes that followed the building of the Midland station produced a triangle of spare land between the station and Euston Road. Over the years this became cluttered with an assortment of completely uncoordinated buildings, known as the ‘Indian Village’. In 1973 the last of these was swept away, and the present [in 1990] single-storey concourse built in their place. It include[d] the BR ticket office and travel centre, which had previously been situated, somewhat inconveniently, halfway along No. 8 Platform. The new concourse also provide[d] other amenities, but even the vastly increased space often [became] crowded as a result from f the greater numbers [by 1990, travelling] on the frequent Intercity services.” [1: p8]

Finally in respect of King’s Cross station, Semmens notes that planning permission for the single story concourse was only granted on a temporary basis and was due to expire in 1996.

B: St. Pancras Station to 1990

At first, the Midland Railway reached London over the Great Northern Railway’s tracks from Hitchin. “Its services by this route began in 1858, but the minimal facilities at King’s Cross made it difficult to accommodate the increasing number of trains being operated by the two companies. Not surprisingly, the Great Northern gave its own trains priority, and the Midland became increasingly frustrated, with no fewer than 3,400 of its services being delayed in 1862 when the Great International Exhibition at South Kensington attracted a lot of special workings. Many of the trains off the Midland were made to use King’s Cross goods yard, and then, in the middle of the summer, the [Great Northern] moved some of the Midland’s wagons out of the way after the latter had been slow to commission their own coal yard. As a result the Midland decided it had had enough, and there was nothing for it but to build its own extension from Bedford into London.” [1: p9]

In the few years that had elapsed since the Great Northern had built its line into King’s Cross urban sprawl had magnified, and the Midland was presented with the immense task of finding a route for its own tracks. “To accommodate its proposed facilities, the Midland was able to buy a large area of land from Lord Somers on the north side of Euston Road, and a suitable reorganisation of the roads in the area could be made to accommodate its new terminus close to King’s Cross. The company was actually able to site it right on the other side of the new Pancras Road, with only the Great Northern Hotel in between.” [1: p9]

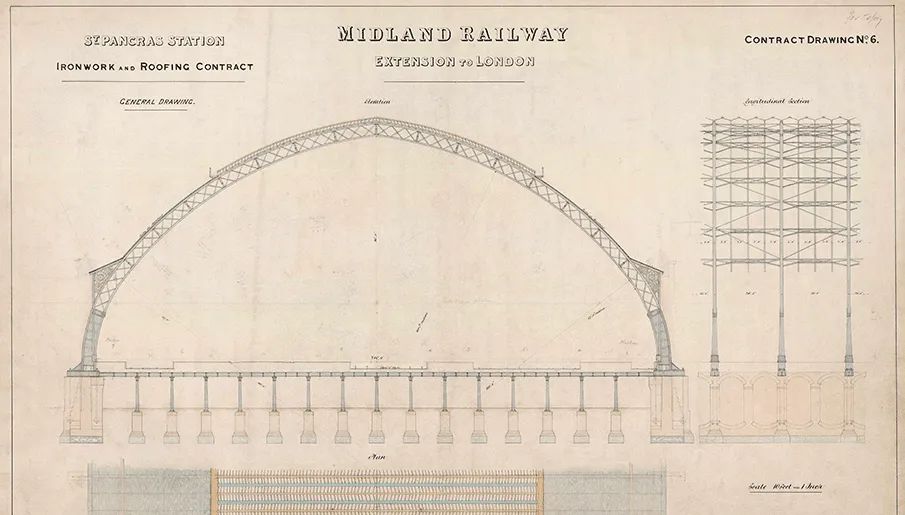

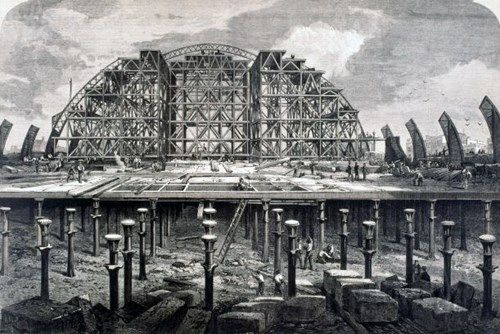

The Midland coped with the barrier presented by the Regent’s Canal by crossing it at high level and maintaining that high level through to the station buffers. This created space under the platforms to store goods brought to London by the railway. Semmens says that “there was one commodity … which had its own special containers, and these formed the new unit of measurement which was adopted for this part of the station. The platforms and tracks were thus supported on a two-dimensional grid of columns, sited 29ft 4in apart, which was chosen because it maximised the storage capacity for barrels of Burton beer.” [1: p9]

“To get the beer into the cellars, beer-laden wagons were pulled into the station, then reversed onto a hydraulic lift just outside the trainshed that took them down. Below, two railway lines ran the length of the stores and there were three wagon turntables, so that wagons could be manoeuvred throughout.” [17]

“St. Pancras has had a long and close relationship with the brewing industry and beer consumption in London. Throughout the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century, beer came from all over the country, and particularly from Burton-on-Trent, to supply thirsty Londoners. A major arrival point was St Pancras where beer was stored in a massive warehouse and in the vaults under the passenger station.” [17]

“Burton’s high-quality attractive pale ales – a contrast to the darker porter beers drunk in London – were well-renowned in the 1820s and 1830s, but getting them to London was very costly and could take three weeks. The railway’s arrival in Burton in 1839 changed that and soon Burton brewers opened rail-supplied agencies nationwide and their trade expanded rapidly. Bass, a major Burton brewer, output rose from just over 30,800 barrels in 1839 to 850,000 in 1879, its biggest market being London where its beers grew in popularity.” [17]

“Before the late 1860s, Burton brewers supplied London by sending their beer via the Midland Railway’s competitors. However, when the Midland planned its main line to London in the early 1860s, Bass agreed to send all their beer with the company as a far as possible, for a fixed price. In return the Midland would provide “Ale Stores and Offices sufficient for the business” at St Pancras. The railway built a dedicated warehouse adjacent to the Regent’s Canal which was connected to St Pancras’s northern goods yard. This held 120,000 barrels and employed 120 men. Bass subsequently became the world’s largest railway customer, and in 1874 it sent 292,300 barrels of beer to London, 36% of its total output.” [17]

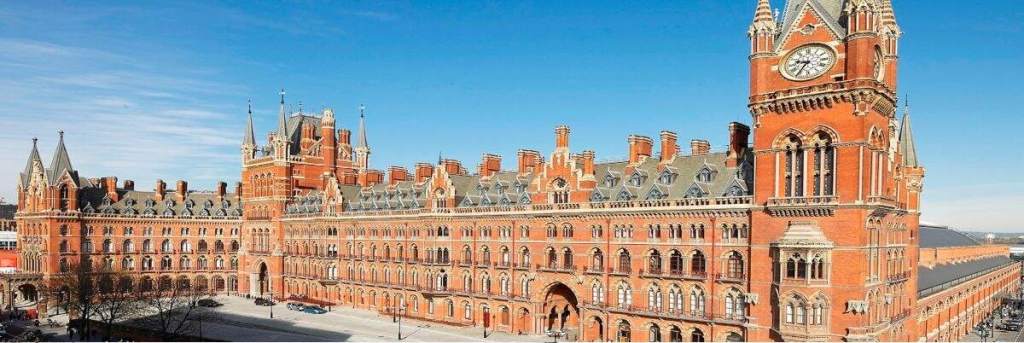

Network Rail says that, “In 1865, a competition was held to design the front façade of the station including a new hotel. George Gilbert Scott, the most celebrated gothic architect of his day, won the competition even though his design was larger than the rules allowed. Construction of the hotel started in 1868 however the economic downturn of the late 1860s meant that the hotel, named the Midland Grand, was only completed in 1876. Striking and self confident, the station and hotel completely dominated its Great Northern neighbours.” [19]

The location chosen for the station was known as Agar Town. It was an area of slum dwellings. The powers-that-be saw an opportunity to clear the area. Semmens tells us that, “several thousand homes of one sort or another were demolished, which resulted in the eviction of an estimated 10,000 people, while hundreds of cats took to the wild, marking out their own new territories in the railway works. There were still more complications, as the Fleet River ran through the site by then little more than a sewer, so it was enclosed in a pipe-while corpses had to be cleared from part of the burial ground for the old St. Pancras church. Another church, St. Luke’s King’s Cross, had to be demolished, and a replacement was built at the Midland’s expense in Kentish Town. Provision was also made for a connection to the Metropolitan Railway, to permit through services to the city. This diverges from the eastern side of the main lines at Dock Junction (originally St Paul’s Junction), nearly three-quarters of a mile from the buffer-stops. It then swings to the west before passing diagonally beneath the terminus on its way to join the Metropolitan at Midland Junction, roughly in line with the end of King’s Cross.” [1: p9]

It is difficult to imagine the upheaval caused to many of the poorest residents of London by the clearance of the slums.

When it was built, St. Pancras Station had “five platforms with a further six carriage roads, which put it ahead of what King’s Cross had at the time. In 1892 the layout was modified when some of the carriage roads were replaced by two more full-length platforms, making the total up to eight, plus the shorter one on the down side. Further changes took place in the early years of nationalisation, and from 1968 there were just six full-length ones, plus the bay.” [1: p10]

“In 1923 St Pancras was transferred to the management of the London Midland & Scottish Railway; the LMS focused its activities on Euston, and so began the decline of St Pancras over the next 60 years. In 1935 the Midland Grand was closed as a hotel due to falling bookings and profit, blamed on the lack of en suite facilities in the bedrooms. It was used instead as office accommodation for railway staff and renamed St Pancras Chambers.” [19]

During WWII, the station played an important role for troops departing for war and children being evacuated from London. Although the station was hit hard during the blitz, there was only superficial damage and the station was quickly up and running. [19]

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, BR allowed the condition of St. Pancras Station to deteriorate and then sought to close and demolish it. “John Betjeman spearheaded a campaign to save the station and hotel, and in November 1967 was successful in getting the buildings declared Grade 1 listed just days before demolition was due to begin.” [19]

Although the buildings were saved, their decline was allowed to continue; the hotel building was mothballed in 1985 and the train shed roof fell into a state of serious disrepair. [19]

Semmens tells us that, “Under the BR Modernisation Plan, diesels took over the main-line and suburban services out of St. Pancras. For many years the former were in the hands of the ‘Peaks (class 45s), hauling rakes of air-conditioned Mark II coaches, but in the autumn of 1982 the first Intercity 125s were drafted to the line. This was slightly earlier than had been envisaged in the original BR plans of 1973, but those arrangements had been based on the Bristol and South Wales sets being cascaded to the Midland after the arrival of APTs on the Western. After the protracted development of the light-weight tilting trains, the position changed, and there were no plans for HSTs on the Midland, but this altered as BR sought to maximise the revenue from its high-speed diesels.” [1: p10]

Writing in 1990, he continues: “Since 1982 the number of these units deployed on the Midland main line has increased, the latest unit having been drafted in after the arrival of the first Intercity 225 set for the ‘Yorkshire Pullman’ on the East Coast Route in October last year. It is of interest that the Eastern Region provides the HST sets for the Midland main line, some from Bounds Green and the others from Neville Hill.” [1: p10]

“For the suburban services out of St. Pancras a special type of diesel multiple-unit was provided. These four-car seats, later to become Class 127, were introduced in 1959, and had Rolls-Royce engines with hydraulic torque converters. They improved the frequency of services on the line, as well as the overall speeds, but by the end of their working lives they had become rather unreliable. They had to continue in passenger operation somewhat longer than intended, because the introduction of their electric successors was held up by the protracted dispute over Driver-Only Operation. The new Class 317 EMUs finally went into service in the summer of 1983, the overhead wires having already been installed into St. Pancras for some considerable time.” [1: p11]

These new EMUs lasted only 5 years in service before being replaced by Class 319 units which were able to operateboth from the 25kV North of St. Pancras and the Southern region’s third rail, to offer a cross-river Thameslink service which was inaugrated by Princess Anne in May 1988. The Thameslink service led to the majority of trains from the North not entering St. Pancras Station. St. Pancras lost most of its suburban services, and by 1990, was primarily an Intercity station. Semmens notes that under the regeneration proposals current in 1990, that role would partly reverse again. [1: p11]

C: Goods & Locomotive Facilites

Semmens notes in 1990 that much of the planned regeneration would be concerned with “the future use of the land that was once occupied by former goods yards and locomotive sheds.” [1: p12] We have already noted these facilities:

- The Somer Town Goods Station of the Midland Railway and its facilities further to the North would not be part of planned regeneration work as they were set aside for the British Library development which we have highlighted above.

- The one-time Great Northern Goods Yard – would become the core of planned regenertion activites – an 85-acre “area situated between the Great Northern and Midland main lines, … bounded on the North by the electrified North London Line and by Regent’s Canal on the South.” [1: p12]

- King’s Cross Top Shed – sat in a small area at the heart of the Great Northern Railway’s goods facilities. It closed in June 1963.

Semmens goes on to describe the area: “potato market occupied much of the east and south-east sides of the yard. It consisted of 40 covered ‘runs’, set at right angles to the main sidings, and each of them could accommodate three or four wagons while they were unloaded by the various merchants. Standage elsewhere in the yards would be required for up to 400 additional loaded wagons awaiting their turn to be shunted into place, and each of these movements would require the use of capstan and turntables, in addition to the yard pilot. Lying to the west of this area were the dispatch roads where wagons and vans could be positioned under cover while being loaded by traders. One of the tracks led down a steep incline to the underground area, which was used for ‘vulnerable’ traffic. Nearby was a building known as the Midland Shed, being. a relic from the time between 1858 and 1867 when that company’s trains reached London over the Great Northern from Hitchin. More tracks served the one-time Grain Warehouse, although it had lost its canal connections” [1: p12] which are shown in the NRM images above.

Semmens continues his description: “Continuing clockwise, the coal area was reached, which had two lines of drops inside the confines of the yard. From one of these, a pair of tracks crossed Regent’s Canal to serve Camley Street Coal Yard, where over 200 wagons could be positioned for unloading using the electric transporter. Earlier still, when the gas works alongside King’s Cross passenger station was operating, that had its own connection across the canal for the delivery of coal straight into the retort-house. Along much of the western boundary of the yard, after the canal has passed under the Midland [Railway], the property of the two railway companies came [1: p12] together. The tracks in the King’s Cross yards finished at right-angles to the lines out of St. Pancras, and were separated only by a wall and the width of the perimeter road. It was here in 1980 that the NRM’s replica of Rocket was transferred from road to rail when it worked the last steam train into St. Pancras, to publicise the Post Office’s commemorative stamps that year.” [1: p12-13]

“Between Top Shed and the North London Line were more sidings, some of which were under cover and handled Sundries, while bricks from the numerous works at Fletton, alongside the East Coast Route near Peterborough, were dealt with in the open. Hereabouts too was the smelly part of the yards, where manure from the railway’s own cartage stables was loaded for dispatch, in addition to some of London’s refuse. Even in 1965 some 40 wagons a day of rubbish from the Chapel and Hoxton Markets were being moved from here to Holwell Sidings on the branch from Hatfield to St. Albans.” [1: p13]

Semmens appears to have the wrong location for Holwell Sidings. Rather than being on the Hatfield to St. Alban’s, they were, in fact in Leicestershire. [50]

Additionally, a single-track line climbed steeply from these yards “to a dead-end parallel to Copenhagen Tunnel, from where there was a trailing connection across all the tunnels to serve the Caledonian Road goods yard away to the east.” [1: p14] While this short branch was still in use in 1965, another facility, which disappeared much earlier, was Cemetery Station, “the remains of which could be seen until the mid-1950s. Like the better-known facilities at Waterloo, this formed the starting point for funeral trains. Those in North London used to run to the graveyard on the east side of the East Coast Main Line, just north of New Southgate, the junction there being controlled by Cemetery Signalbox, now demolished. The final traces of the station opposite King’s Cross Goods Yard were swept away during the construction work that went on here for the Victoria Line.” [1: p14]

In 1965, King’s Cross Goods Yard still employed more than 1,000 men. The main terminal close in 1974 and by 1990 much of the yard’s activities had ceased. Semmens noted in 1990 that, “Freightliners ha[d] come and gone, but three separate aggregate/concrete facilities still operate[d] in the area to the north of the Top Shed. They [were] served by regular Railfreight workings, usually hauled by a pair of class 31s. There [were] also sufficient other operations to justify the presence of an unofficial caravan close to the Grain Warehouse providing food and drinks for those who work[ed] in the area. The various listed buildings and structures remain[ed], but many of the others ha[d] deteriorated since closure.” [1: p14]

2: Regeneration: First Thoughts

Back in Victorian times St. Pancras Station was built alongside King’s Cross because of the commercial competition between two different railway companies. This position was not changed by the Grouping, as, in 1923, their ownership passed to the LMS and LNER respectively, which were still rivals, particularly for the Anglo-Scottish business. Semmens notes that in 1990, the two stations were still operated by two different regions, but their common ownership during since 1948 had nevertheless provided opportunities for rationalisation and cooperation. [1: p15]

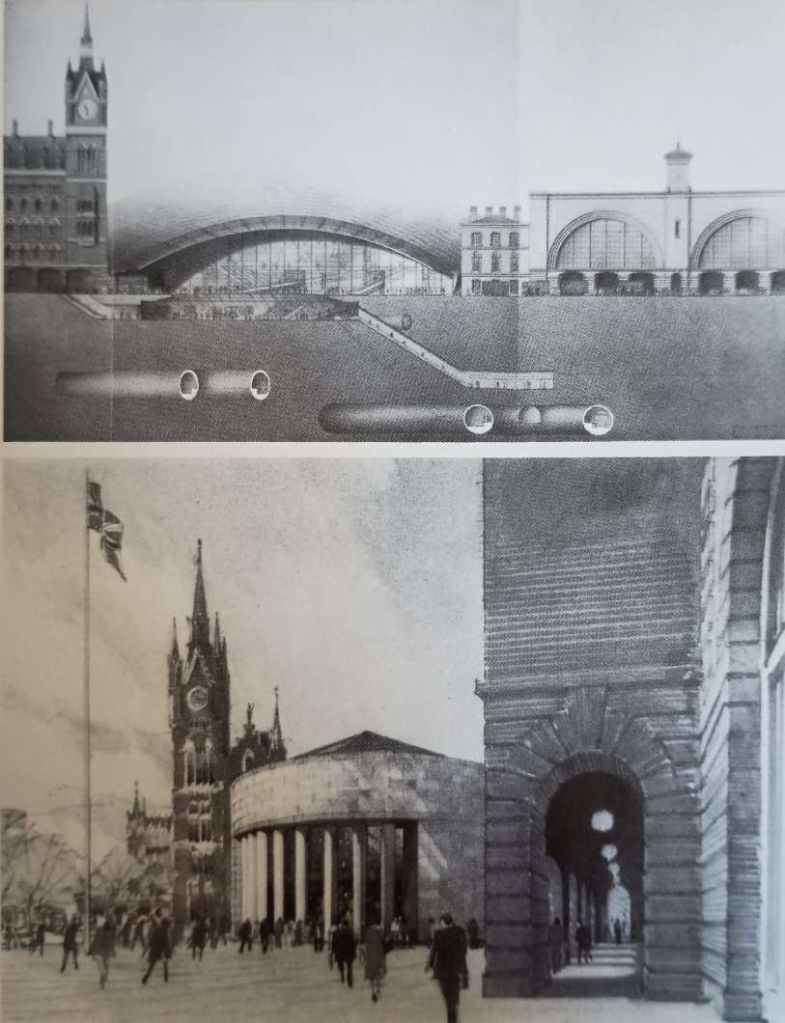

“In 1966, the year after Lord Beeching had returned to ICI, proposals for combining King’s Cross and St. Pancras were first aired, with the latter being closed. Its suburban services would have worked through the tunnels to the City, while the main-line trains were to have been diverted into King’s Cross, where one scheme envisaged a heliport on the roof. A two-storey concourse building was to have been constructed across the front of King’s Cross, while a new 300ft tower to the north-west of the station would have become the new BR headquarters. The St. Pancras hotel would have been demolished and replaced with a new office block.” [1: p16]

These early plans were stymied when St. Pancras Station and the Hotel were ‘listed’ in 1967. Suggestions that it should be a sports centre or a transport museum with trains diverted elsewhere, came to nothing in 1968 when rationalisation of railway facilities was abadoned.

Semmens says that, “a decade and a half later, other, much more friendly, proposals were to materialise for the two stations, which would enable them to become the nucleus for the regeneration of the whole area. … It was in the latter half of the 1980s that British Rail offered potential developers the opportunity to submit ideas on how to revitalise the whole 130 acres of their land around King’s Cross. … The developer’s brief was the regeneration of the land North of the two stations, which was to be fully co-ordinated with new station facilities and railway works. In particular, provision was to be made for a sub-surface station below the existing platforms at King’s Cross, which would ultimately benefit the Thameslink services due to be inaugurated in May 1988.” [1: p17]

Two consortia were invited by British Railways to submit plans which the public could study at an exhibition held in the St. Pancras Undercroft at the beginning of 1988. They were:

1. Speyhawk, working in conjunction with Sir Robert McAlpine & Sons (Speyhawk/McAlpine).

2. London Regeneration Consortium (LRC), working with two separate groups of architects, Foster Associates, and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

Semmens notes that “although only open for a relatively short time, the exhibition drew the public’s attention to the plans, and created considerable interest in architectural circles. In addition to the displays, which included models of the main proposals, both consortia produced some effective printed material which enables us to recall what was being planned at this stage of the project.” [1: p17]

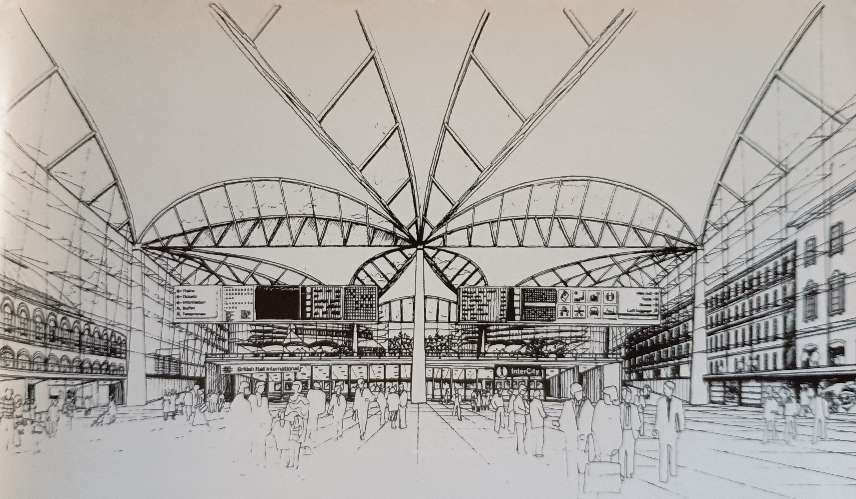

Semmens says that “the individual styles of the two Victorian stations made it difficult to link them together architecturally, and three very different proposals for the new concourse resulted, as shown in the illustrations. Speyhawk/McAlpine, who were already involved with BR in the redevelopment of the hotel at St. Pancras, went for a ‘solid’ design. with a classical, stone-built, rotunda serving as the main public entrance. On the other hand, the LRC’s two architectural partners both came up with proposals that included much more glass in their construction. Foster Associates proposed a huge glazed vault, filling the whole gap between the two stations, while Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s plans were for a much smaller, fan-shaped, structure with an unusual roof profile.” [1: p17]

These were only outline schemes, but suggested very different ways in which the area around and to the North of the two stations could be developed. “All three schemes involved covering in the railway tracks out of King’s Cross, between the twin train-sheds and Gas Works Tunnel, which would have meant that trains would have first emerged into daylight at the north end of this tunnel. Speyhawk/McAlpine also proposed building over the Midland’s tracks for some distance alongside Pancras Road, and included a monorail link from their proposed concourse to a new Maiden Lane station on the North London Line.” [1: p17]

The proposals submitted by the London Regeneration Consortium were preferred by British Rail, and they became the designated developers. However, the brief that they began working to was altered significantly as the 1980s gave way to the 1990s because of a significant “upsurge in railway travel … sweeping across Europe in response to modern attitudes to mobility and the environment. In particular the significance of the Channel Tunnel began to be perceived, and the need for a second London terminal/interchange to serve those parts of the country north of the Thames emerged.” [1: p17]

Semmens supplement to The Railway Magazine was effectively a position statement, outlining the state of play at the beginning of the 1990s. New proposals were before Parliament, designed to enhance the railway facilities of the UK considerably, in addition to creating a whole new urban area out of the wastelands of the former goods yard at King’s Cross. [1: p17] That redevelopment was given greater significance by the need to accommodate the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (HS1), which would bring high-speed rail services to London. [31]

In 1990, the UK Parliament considered and approved the British Rail development plans, including the merging of the stations and the creation of a new low-level station. [32] The Select Committee drew attention to the financial links between the proposed office and commercial developments on the railway lands behind King’s Cross and St. Pancras stations and the proposal for the new station to go ahead. [33]

In 1991, 1992 and 1993, the King’s Cross Railways Bill was debated in the House of Commons and the House of Lords [34] but development did not take place at that time. In 1996, the decision was taken to locate the HS1 terminal at St. Pancras (a change from the original intention for it to be at Waterloo Station).

3: The Scheme Current in 1990

Semmens tells us that in November 1988, the British Railways Board and London Underground Limited lodged their private ‘King’s Cross Railways’ Bill with Parliament, seeking authority “to construct works and to purchase or use land at King’s Cross in the London boroughs of Camden and Islington; to confer further powers on the Board and the Company; and for other and related purposes”. While this may sound quite modest, its passing will set in operation the second most important railway project in Britain this century, and encourage urban redevelopment of 134 acres, worth some £3 billion, as well as providing 1,800 new homes and creating the potential for up to 30,000 jobs. Remarkably little detail of how this will be achieved emerges from the four parts, 31 sections and five schedules of the Bill itself, but this was supplemented by 35 days of evidence presented by BR to the MPs considering it at the start of its committee stage.” [1: p17]

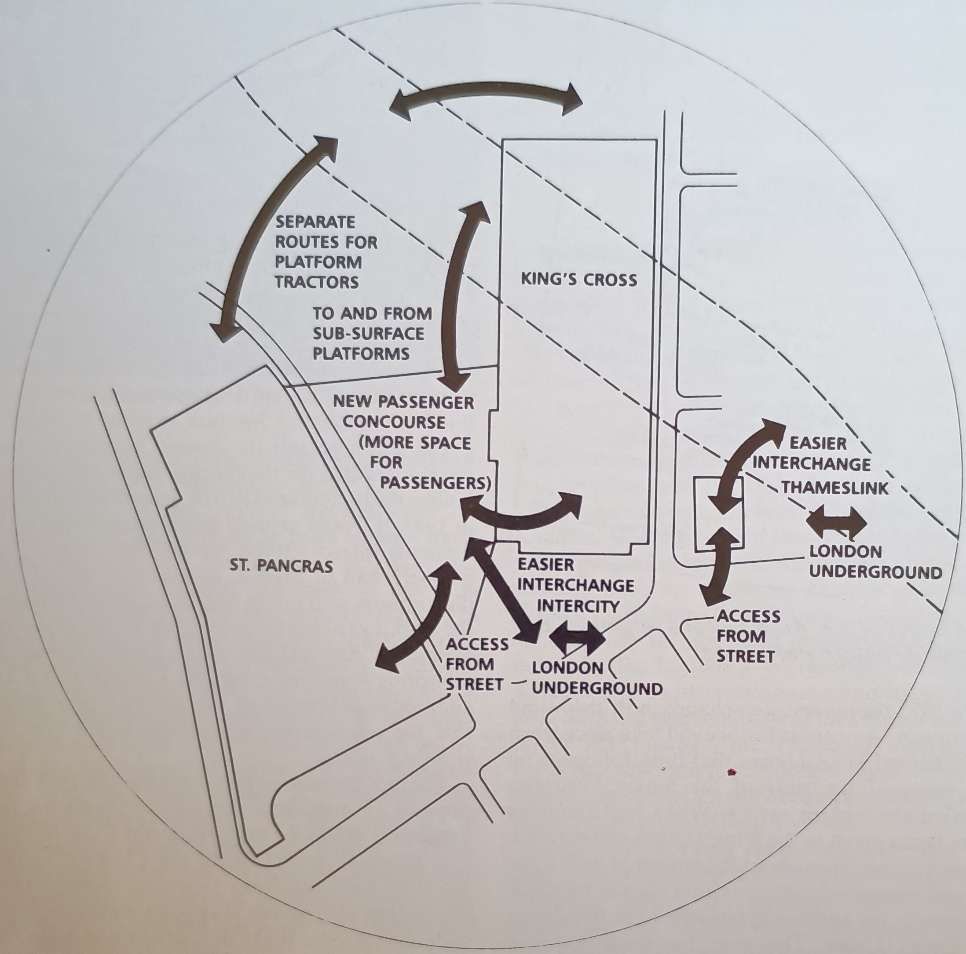

“King’s Cross, St. Pancras, Thameslink and the London Underground interchange connected with these stations are currently used by some 270,000 passengers every weekday. Many of these travel by the BR Intercity services using both the main line stations, with Anglo-Scottish trains arriving and departing every half hour for considerable periods of the day. The popularity of the East Coast Route … increase[d] still further with the travelling public after the full electric services [came] into operation in May 1991, when many of the trains [began to] run through to Glasgow.” [1: p17-18]

Long-distance passengers were “supplemented by those using the Network SouthEast suburban trains, including the Thameslink services running right across the heart of London. From King’s Cross Underground it is possible to travel to more than 60 per cent of the Underground stations without changing trains, and all the other BR main-line termini can be reached direct, except Waterloo, which requires one change. All five London airports [were soon to] be within one hour’s journey by train from King’s Cross, either direct or with easy changes, and the rail link right into Stansted [was due to] begin operations in March 1991. … The King’s Cross area [also] serve[d] as a significant bus interchange.” [1: p18] Towards the end of the 1980s, there had been a steady increase in the number of passengers using all these services.

In 1993, “the biggest step-change in British and European-transport history [was due to] take place when the Channel Tunnel open[ed] that June, following on the heels of the start of the Single European Market six months earlier. When first thoughts were being given to the King’s Cross regeneration project, predictions about the impact of both these factors suggested that provision should be made eventually for additional facilities to be developed at King’s Cross. The need for them was not expected to arise, however, until into the 21st Century. The position was changing rapidly, though, and in July 1988, British Rail published its report on the long-term route and terminal capacity for its Channel Tunnel train services. which indicated that both could become congested appreciably before the year 2000.” [1: p18]

“This radically changed the emphasis on the ideas for the new railway facilities required at King’s Cross, which became the obvious location for the second terminal for the through trains to Europe. Unlike the first terminal, to be opened at Waterloo in 1993, it would provide direct interchange with domestic Intercity trains serving the whole of the northern half of Britain … and could also be made to facilitate the workings of the through trains to and from the Continent. Any such scheme for a new major set of platforms would be extremely expensive, but an additional advantage of the King’s Cross site is that the regeneration possibilities could provide welcome finance.” [1: p18]

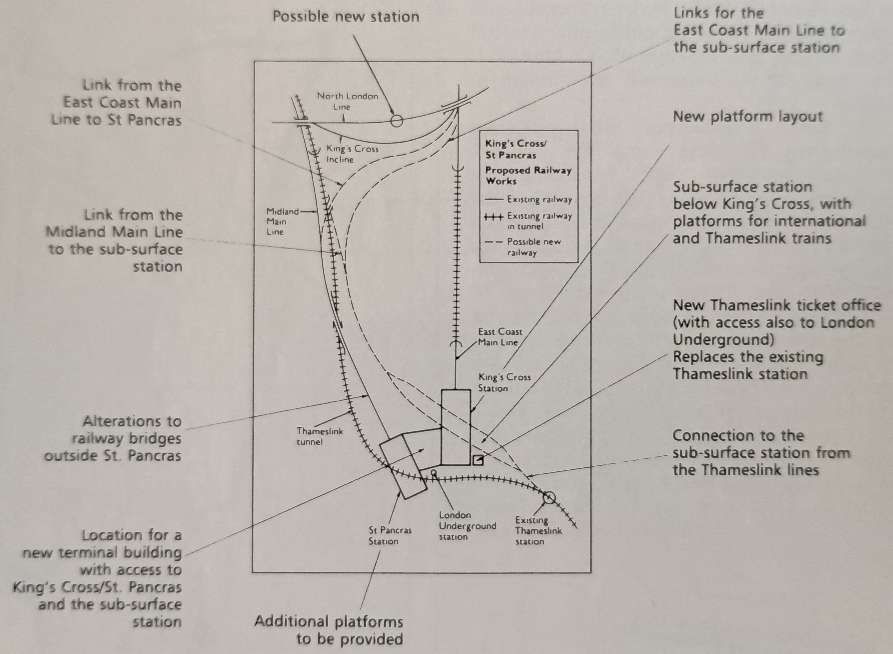

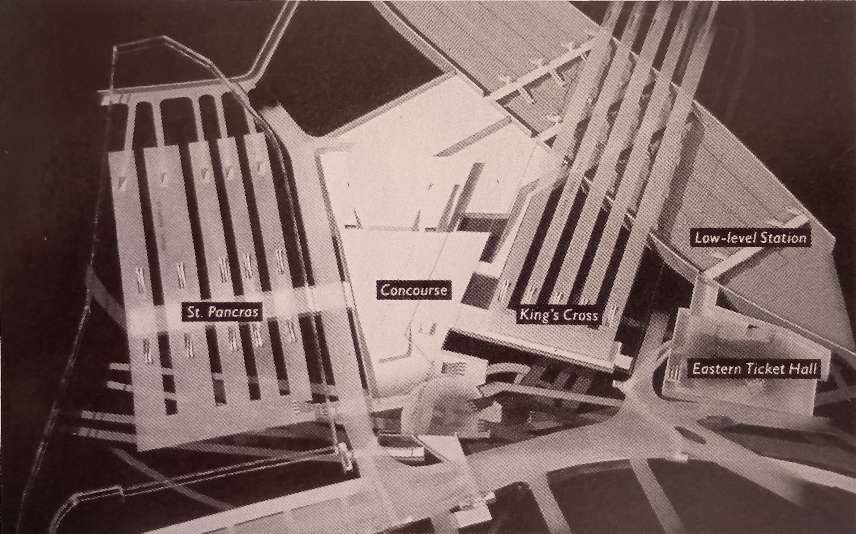

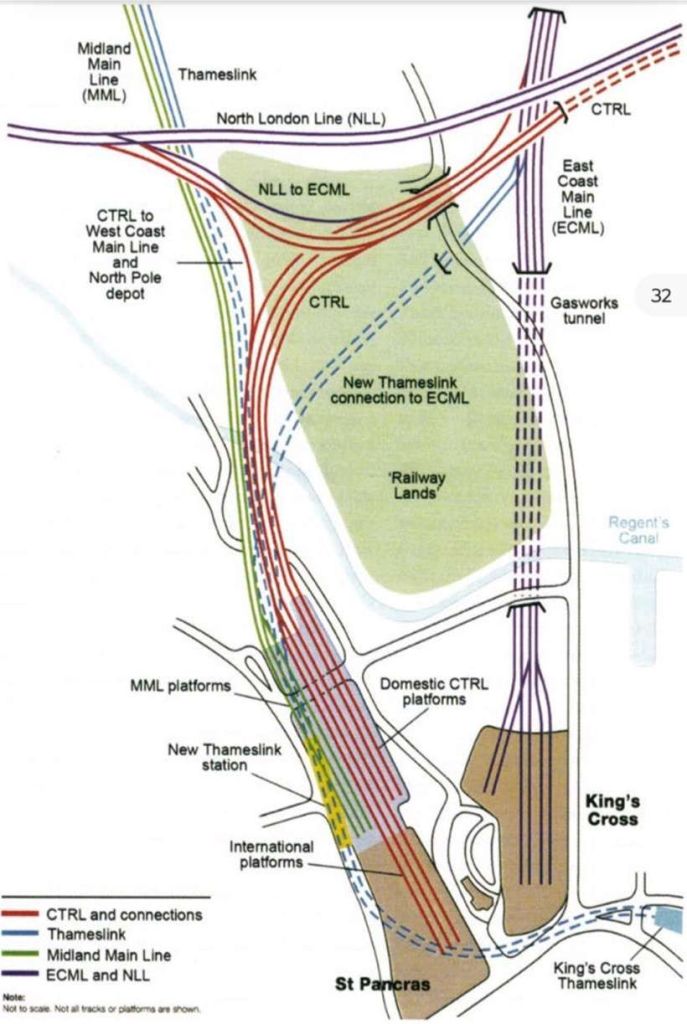

“The … proposals … included in the 1988 Bill, provide[d] for eight new sub-surface platforms, set diagonally below the main station at King’s Cross, four of which would be for the Channel Tunnel services. To reach these from the north, a new connection [would be] required, swinging westwards in a wide curve from Belle Isle, at the south end of Copenhagen Tunnel, as it descends. Just north of the point at which it passes under Regent’s Canal, it is joined by a connection off the Midland main line, so trains from both routes can use the new platforms. At present the sharp curves through the tunnel under St. Pancras impose major restrictions on the type of rolling stock that can use the Thameslink route, and the new arrangements will remove these.” [1: p18]

In addition, “this curve [would] enable Thameslink services off the Great Northern suburban lines which [could not then be operated]. Even if the York Road and Hotel Curves were to be reopened at King’s Cross, the tight clearances caused by the tunnels and curvature would necessitate the provision of even smaller rolling stock than the [then] present class 319s. BR also ha[d] a Bill going through Parliament for the construction of a new chord at West Hampstead, which [would] provide a connection between the lines out of St. Pancras and the West Coast Route, enabling Thameslink services to be extended that way too if required. The through Channel Tunnel trains serving the northern part of Britain [would] also be able to use these links to reach the East and West Coast Main Lines. At the south-east end of the new King’s Cross sub-surface station, the platform roads [would]. converge into the two tracks which form the present Thameslink route.” [1: p18]

Realignment work then underway in “the Ludgate Hill area [would] remove the existing clearance restrictions at that end of the link, and only minimal widening work [would be] necessary between King’s Cross and Farringdon to enable the passage of the largest coaches on BR. The present King’s Cross (Thameslink) station [would] disappear, and passengers using it [would] also benefit from the change. The main entrance to this [was] situated a considerable distance away along Pentonville Road, and require[d] a long walk to reach it, either through underground passageways or across busy roads. Although the passenger facilities there [had been] recently improved, the platforms [were] short and comparatively narrow, and there [was] no room for them to be extended in any direction. A sub-surface ticket hall for the new Thameslink platforms [would] be built on the corner of York Way and Pentonville Road, beneath the Bravington block of shops, right opposite the south-east corner of the main station at King’s Cross.” [1: p19]

“Commuter traffic on the Great Northern lines [was] also expected to continue to grow. The [then] present suburban platforms [would] not accommodate 12-coach trains, and already in peak periods outer suburban sets [could] be found competing with Intercity trains for platform space in the main station. To deal with this problem, it [was] planned to switch all the Network SouthEast trains into St. Pancras by a new surface connection which [would] run across King’s Cross Goods Yard, and join the Midland’s tracks just behind the site of Top Shed. To accommodate these extra workings in St. Pancras, the number of platforms [would] be increased to ten, a task that [would be] comparatively straightforward, thanks to the method of construction adopted back in the 1860s. Bridge No. 1, immediately outside the station, [would] have to be widened, and as this [was] situated over what amounts to a six-road intersection, it [would] involve some clever engineering.” [1: p19]

The existing platforms at King’s Cross would need to be lengthened to accommodate the longer East Coast Route trains needed to meet demand. At King’s Cross, as at St. Pancras the station layout would need improvement to allow higher arrival and departure speeds to be achieved. Track would need to be relaid through Copenhagen and Gas Works tunnels.

“New platforms and tracks are of little use unless better facilities are also provided for the passengers, and considerable thought [had] been given to this aspect of the proposals as well. The idea for the new concourse beside King’s Cross Station [had] been developed, and a new design for it [had] been produced by Richard Paul of Norman Foster Associates. Like the earlier London Regeneration Consortium proposals, it [would] be clad in glass, and the triangular roof, covering 8,300 square metres, [would] be supported by just nine columns, all except one of them situated along the walls. People entering the station from the street [would] approach the concourse down a wide semi-circular ramp from the south-east. Escalators [would] connect with the improved interchange arrangements for the London Underground’s five lines, which [would] be constructed to take into account the long-term recommendations of the Fennell Report on the 1987 escalator fire. Passengers arriving by car or taxi [would] use a special area to the north of the new concourse, … equipped to deal with the different types of flow involved.” [1: p19]

Great care had been taken to ensure that the concourse was user-friendly; due allowance being made for ‘meeters and greeters’ and the dwell-times that will result. As shown in one of the illustrations, the ticket office and travel centre would be set across the wide north end, “with the main catering facilities at mezzanine level above them. The usual forecourt retailing activities [would] be located along the walls, and kept low so that views of the two main station buildings through the glass walls [were] not obscured. The floor of the concourse [would] be below street level, to facilitate the connections required to the various platforms.” [1: p20]

“Four of the new sub-surface platforms [would] be dedicated for use by the international services to and from the Continent, and they [would] have their own inward and outward Customs and immigration facilities, although these activities [were expected to] take place on the trains in the case of the through services between the Continent and the northern parts of the country. When the Channel Tunnel open[ed] in June 1993, the schedule from Edinburgh to Paris [was expected to] be approximately eight hours. To reach the West London Line through Olympia, these services [would] use either the ‘King’s Cross Link’ with the North London Line … or the Harringay curve. After the new low-level station [had] been completed at King’s Cross, which would be in 1996 at the earliest, half an hour would be cut from the timings of all the through international trains using the East Coast Route.” [1: p20]

“The international trains would then still be using the existing lines through Kent, but the completion of the European Rail Link, after 1998, [would] enable an additional 30-minute cut in timings to be made, to the great advantage of the millions of international passengers who [would] use the route each year thereafter. Its opening [would] bring Edinburgh within seven hours of Paris, and 6 hours from Brussels, the former being only an hour longer than the ‘Coronation’s’ London-Edinburgh timing, which was the fastest ever scheduled in the days of steam. From 1996, it [was] expected that there [would] be one international train an hour in each direction from Waterloo and the same number from King’s Cross, but this represents only about a quarter of the long-term capacity of both terminals. From King’s Cross, St. Pancras and Euston stations up to ten Intercity trains an hour [in 1990 departed] for the Midlands, Northern England and Scotland.” [1: p20]

“The completion of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link [would] signal the start of the high-speed domestic services from King’s Cross to the towns and cities in Kent. With the eight-coach Class 342 ‘Kent Express’ units running at up to 125 mph, the journey to Dover could take as little as 60 minutes. … Cross-London Intercity trains [might also run] this way, although they might presumably have [had] to be hauled by dual-voltage electric locomotives, as it is unlikely that the diesel fumes from the shortened Cross-country HSTs would be welcome in King’s Cross Low Level.”

Provisions were made within the Bill for the purchase of land outside British Rail’s ownership. Some temporary road diversions were envisaged as was the need to remove and later replace the listed lock-keeper’s cottage alongside the canal. A ‘listed’ gas-holder would need to be dismantled and rebuilt. A nature reserve would need to be removed and replaced by a larger one. semmens noted that only 29 homes would be demolished and the development would provide 1800 new dwellings. He noted too that a period on at least 20 years would be likely to relapse from the Act receiving Royal Assent before the scheme would be completed.

British Rail was given the green light by MPs to carry out a multi-million pound redevelopment of King’s Cross and St Pancras stations and as the 1990s unfolded, the UK Government established the King’s Cross Partnership to fund regeneration projects in the area. London and Continental Railways (LCR) was formed to construct the railway and received ownership of land at King’s Cross and St Pancras stations in 1996. After the millennium, work on High Speed 1 (HS1) began, providing a major impetus for other projects in the area.

4: St. Pancras Midland Grand Hotel

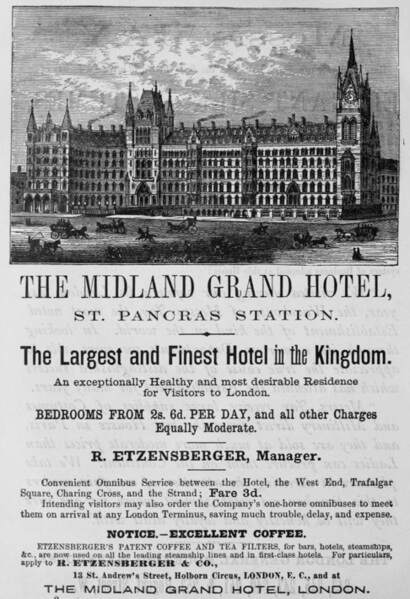

Before going on to consider developments after Semmens was writing in 1990, it would be good to hear what Semmens had to say about the hotel which fronts Barlow’s trainshed. Designed by Gilbert Scott, the hotel was no more than a series of foundations when the station opened in 1868. Five years would elapse before the building was complete.

The Midland Railway over stretched its finances in building its extension into London. It downsized the design of the hotel, removing an eighth floor which would have housed the headquarters of the railway company after an intended move from Derby. The project programme was allowed to drift to aid the company’s cashflow. Semmens describes the hotel as “the finest example of non-religious Victorian Gothic in Britain, … much of the detail was adapted from the architect’s plans for offices in Whitehall which never materialised.” [1: p22]

Construction of the Midland Grand Hotel took place between 1868 and 1876 and was completed in various stages with the East Wing opening on 5th May 1873 and the rest followed in Spring 1876. Altogether, the hotel fabric had cost £304,335, decoration and fittings £49,000 furnishings £84,000, adding up to a not-inconsiderable £437,335. [37]

The completed building had used 60 million bricks and 9,000 tons of ironwork including polished columns of fourteen different British granites and limestones.

Despite all its magnificence, “the building had a number of serious drawbacks, which in time were to prove its downfall as a hotel. Although it was equipped with hydraulic lifts-receiving their power from the high-pressure water mains that used to run below the main highways in London and the first revolving door in the capital, an examination of the ridge of the Mansard roof above the dormer windows will reveal rows of chimneys. These came from the open fires in the various rooms, private as well as public, which were neither easy to service nor particularly efficient as sources of heat. … Only 12 years after the Midland Grand Hotel had been completed, work started on a rival hotel in another part of London which was to eclipse it in comfort and appointments. Funded in part from the profits of the theatre of the same name, the Savoy Hotel in the Strand was completed in 1889. During its construction, the builder asked whether, in the light of the number of bathrooms being installed, the management were expecting to entertain amphibians. While not all the bedrooms originally had their own bathroom, no fewer than 67 were provided initially. … The Midland [Grand] did not have bathrooms on anything like this scale, and not many decades were to pass before those who used hotels of this standing expected such facilities in every room. In the same way as the Midland Grand Hotel could not install central heating at an economic price, they were unable to provide all their bedrooms with baths ‘en-suite’.” [1: p22]

The Midland Grand was taken over by the London, Midland and Scottish Railway in 1922, its facilities were already outdated and it had become too expensive to run and refurbish. the demand for high-class hotel accommodation in the King’s Cross/St. Pancras area declined in the 1930s and the hotel closed in 1935. [1: p23][37]

Now renamed St Pancras Chambers, the premises settled down to a somewhat less glamourous existence as railway offices. It retained this role until 1983. [1: p23][37]

The building survived the bombing raids of the Second World War but found itself threatened with complete demolition in the 1960s. As we have already noted, in 1967 it was awarded Grade 1 listed status in recognition of its importance as an example of high Victorian Gothic architecture. [37]

In 1983, the building failed its fire certificate and was closed down, remaining empty for many years.

Semmens continues: “the Speyhawk/McAlpine development proposals for the St. Pancras Grand Hotel, as it [was to] be titled, predated the main King’s Cross Regeneration Project. They [involved] the original hotel buildings … [and] the undercroft.” [1: p23] No Act of Parliament was required but by 1990 the plans had already received outline planning permission from the local authority. “Their implementation, however, depend[ed] closely on the larger BR scheme, not only because of the general upgrading of the area that will then result, but because the links from the new concourse to the two main-line stations will require ‘corridors: through the undercroft.” [1: p23]I

Included in the Speyhawk/McAlpine scheme, and sited in the undercroft were:

- a leisure centre;

- a shopping precinct (St. Pancras Plaza);

- a cat park; and

- a multi-screen cinema.

Above ground the scheme allowed for:

- the conversion of the station booking hall into a hotel brasserie or coffee shop;

- the conversion of the original hotel entrance into a night club;

- the meeting of fire regulations by isolating the grand staircase to make it a self-contained area;

- the installation of a modern central heating system; and

- the provision of en-suite bathroom facilities (a challenge in a listed building).

These developments had to be set alongside significant work to the fabric of the building. [1: p23]

Planning permission was granted in 2004 for the building to be redeveloped into a new hotel. [38]

The main public rooms of the old Midland Grand were restored, along with some of the bedrooms. The former driveway for taxis entering St. Pancras station, passing under the main tower of the building, was converted into the hotel’s lobby. In order to cater for the more modern expectations of guests, a new bedroom wing was constructed on the western side of the Barlow train shed. [38][39]

As redeveloped the hotel contains 244 bedrooms, two restaurants, two bars, a health and leisure centre, a ballroom, and 20 meeting and function rooms. [37][38] The architects for the redevelopment were Aedas RHWL. At the same time, the upper floors of the original building were redeveloped as 68 apartments by the Manhattan Loft Corporation. [38][40]

The St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel opened on 14 March 2011 to guests; however, the formal Grand Opening was on 5 May – exactly 138 years after its original opening in 1873.[38][41]

The building as a whole including the apartments is still known as St Pancras Chambers. [38] Its clock tower stands at 76 m (249 ft) tall, with more than half its height usable. [38][42]

5: Bringing Things Up-to-date (2025)

By 2025, the redevelopment of the King’s Cross area has been completed. The final form of the development and of the railway provision is somewhat different from that described by Semmens.

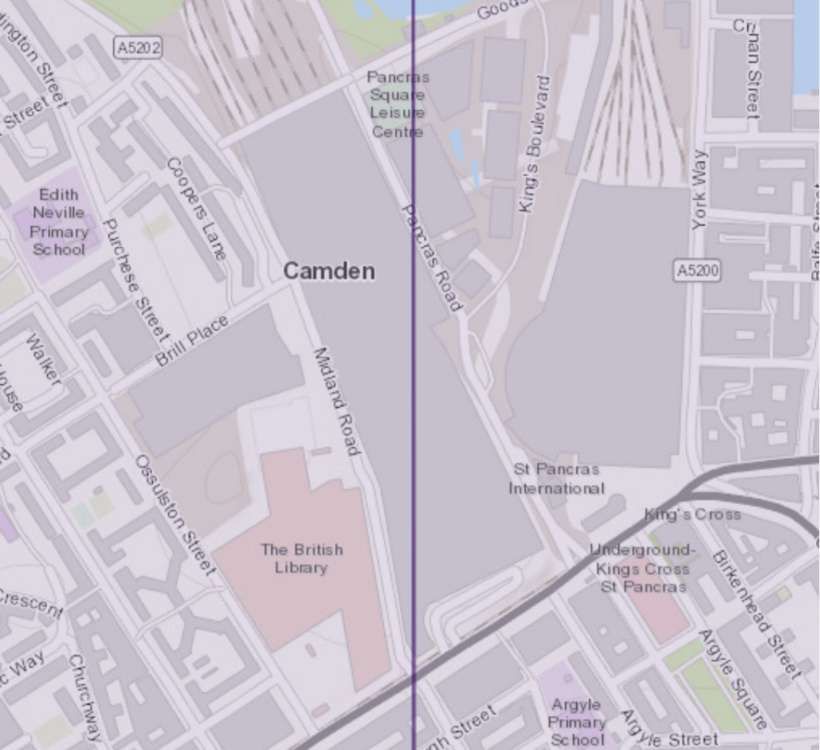

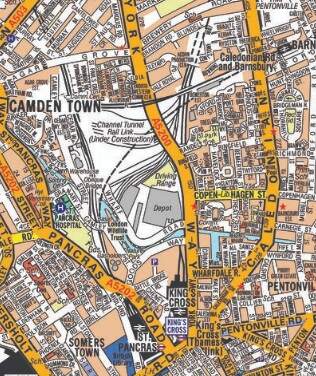

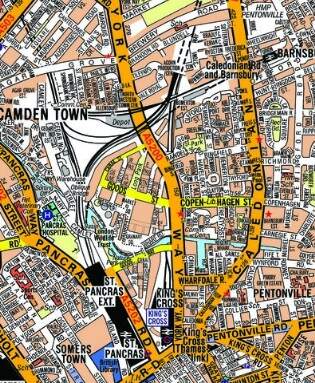

Two street maps of London illustrate the changes to the site between the late 1980s and 2025. [30]

Particularly different from earlier plans, is the way in which the international high-speed and Channel Tunnel railway traffic has been accommodated within the overall project and we will come back to those changes later in this article.

It is first worth noting that King’s Cross has undergone a substantial renaissance, one that has been described as “one of the most exciting and vibrant urban regeneration schemes in Europe.” [25]

King’s Cross Central has evolved from an idea on paper to one of the most sought after places in London. The routes and spaces within the development provided a flexible framework for sequential development on the site, and have successfully created a sense of place during each phase of the development. Significantly, those routes and spaces link the railway stations to the former derelict Granary Building and beyond. [30]

The plan above shows the revised concourse design which was finally adopted. It is attached to King’s Cross Station building and not to St. Pancras Station building. Redevelopment of King’s Cross Station commenced in 2008, the contract duration was 42 months with completion in 2012. The contract cost £550 million. [23]

The contract involved: constructing a 1,700 tonne geodesic steel and glass dome over the top of the London Underground ticket hall; reconstruction of platforms 1 and 8 and shortening of platforms 5 to 8 to enlarge the concourse; a new glass footbridge and escalators serving platforms 1 to 8; a new 12 car platform (300m); 4,000 m² of refurbished office space; 20,000 m² of renewed main shed roof; and 2,500m² of photovoltaic panels to generate 10% of the station’s power needs. All of which was undertaken without impacting normal station operations. [23] The main objective of the project was to provide station capacity to handle projected peak hour passenger demand within a more attractive retail and transport interchange environment.

The main outputs were: a new western concourse, four times the size of the existing one (from 2,000m² to 8,000m²); a wider range and quality of commercial outlets; better interchange with London Underground and St Pancras International Station; renewed main shed roof to provide better lighting. [23] “The historically accurate restorations and modern architectural and servicing interventions won 35 international design awards, including the coveted Europa Nostra prize for cultural heritage. Internationally, the station is widely regarded as one of the most successful large-scale historic building transformations of recent times, and is a fitting gateway to the 35ha regeneration scheme immediately to the north.” [24]

Islington Gazette comments: King’s Cross is now ‘vital piece’ of London economy after regeneration. [27] The area North of the two railway stations is now “a haven for offices, chain shops and restaurants.” [27] A study, by Regeneris, “was commissioned by Argent, one of the two companies behind the redevelopment. Regeneris said the project has helped create 10,000 jobs and £600million for the economy per year.” [27]

Rowan Moore comments that, “The two-decade transformation of the industrial site north of King’s Cross station in London, once notorious, now a pleasant enclave of offices, homes, shops, bars and boulevards, is essentially complete. It’s a huge success. … The near quarter-century, kilometre-long, 67-acre project to redevelop King’s Cross in London is a monument of its age. It is the urban embodiment of the Blair era in which it was conceived, of the third way, of the idea that market forces, wisely guided by light-touch government, can be a power for good. It will get into the history books about cities (if such things are written in the future), representing its time in the same way that John Nash’s Regent’s Park represents the Regency and the Barbican represents the 1960s.” [28]

“The development runs from the terminuses of St Pancras and King’s Cross through a central open space called Granary Square, to a dense cluster of blocks and towers at its northern end, formed around a long oblong lawn with [Alison] Brooks’s building at its head, which includes most of the most recent additions. It is phenomenally successful, both commercially and at achieving its stated aims. Its developers, Argent (selected in 2001), set out to achieve somewhere like the sort of cities where you might want to go on holiday, with open spaces that one of its architects calls “incredibly pleasant”, and – contemplating children from surrounding areas playing in its fountains, or office workers and art students lounging in its open spaces – it has certainly done that. It has created, in its 50 new and restored buildings, about 1,700 homes, more than 40% of them affordable, 30 bars and restaurants, 10 new public parks and squares, 4.25m sq ft of offices and capacity for 30,000 office jobs.” [28]

6. St. Pancras International and Rail Decisions & Developments

The strategic decision was taken to focus international and domestic high-speed services at St. Pancras. The decision to have St Pancras as the terminus for the CTRL was heavily driven by the ambition to regenerate East London.

HS1 (previously the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, or CTRL) is a high-speed line which connects the Channel Tunnel with London, via Stratford, Ebbsfleet and Ashford in Kent. Eurostar services began serving St. Pancras on opening. Prior to the opening of the high-speed line, Eurostar services operated from Waterloo International. Domestic high-speed services between St. Pancras and Kent were introduced in December 2009.

HS1 was initially planned to tunnel through south-east London to an underground King’s Cross international station much as discussed by Semmens. However, in 1994 this plan was rejected, and the decision was taken to approach London from the east, terminating at St. Pancras. [43: p21-22]

In 1994, St. Pancras station was seen as not realising its full potential as a station. The original route involved expensive tunnelling under listed buildings, a medieval hospital and the King’s Cross gasworks, while the route into St. Pancras could follow the existing North London Line. [43: Appendix B]

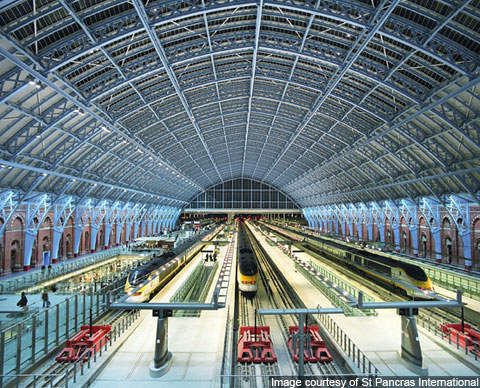

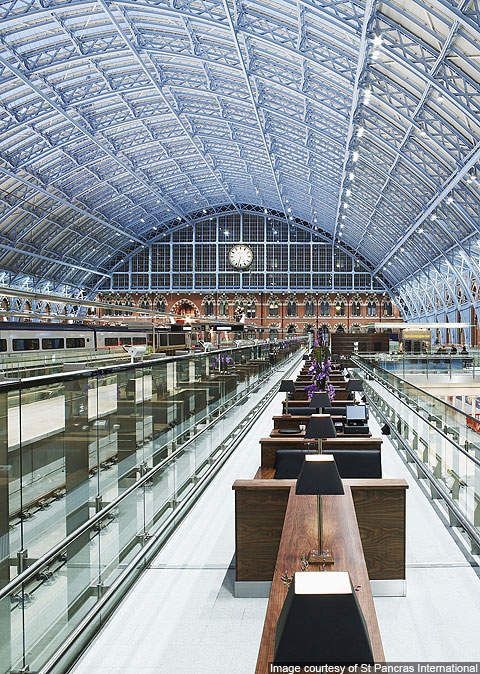

“As a result of the decision to locate HS1 at St. Pancras, the station was extended to hold extra platforms and extend existing platforms to the required length for Eurostar. On completion there were 13 platforms: 4 for Midland Main Line services on the western side, 6 for international services in the central train shed, and 3 for HS1 domestic services to Kent on the eastern side. On opening, HS1 could carry up to 8 Eurostar services per hour as well as up to 8 domestic high-speed services per hour, along with two open access paths. … Once St. Pancras opened to international services in 2007, Eurostar moved their operations to St. Pancras and stopped serving Waterloo. Domestic HS1 services launched in 2009 using new Class 395 ‘Javelin’ trains, as part of a major revision of the Southeastern timetable in December 2009.” [43: p22]

“As a result of the work to bring HS1 to St. Pancras and the increased services this would bring to the area, the King’s Cross Thameslink station and King’s Cross St. Pancras underground station needed to be expanded to handle the additional passenger traffic. The decision to relocate the King’s Cross Thameslink station to St. Pancras was originally intended to accommodate the Thameslink Programme, which would introduce additional and longer trains connecting North and South London through the Snow Hill tunnel. … When the new Thameslink station was constructed, it was driven by three purposes: to accommodate the expanded Thameslink network, to improve safety and passenger experience at the station, and to serve the new Eurostar/HS1 terminal at St. Pancras. The new St. Pancras Thameslink station opened in December 2007, separately from and in advance of the wider Thameslink Programme. … Regarding the Underground station, a key recommendation of the Fennell report following the 1987 King’s Cross Fire was taking action to improve passenger flow, ease congestion and improve safety at the King’s Cross St. Pancras Underground station. In response, the London Underground (King’s Cross) Act was passed in 1993. Two new ticket halls were constructed: the western ticket hall and northern ticket hall. The western ticket hall was opened in 2006, doubling the station capacity at the time to serve HS1, Thameslink and visitors to the 2012 Olympics. The northern ticket hall opened in 2009, further doubling station capacity and reducing congestion. It also allowed step-free access to the Underground platforms and was described as essential to effectively managing future passenger numbers. This ticket hall also connects directly to the HS1 domestic station via a direct subway link.” [43: p22-23]

Refurbishment of St. Pancras to receive Eurostar services required a highly complex programme of expansion, modernisation and restoration. St. Pancras Interational Station became a key urban hub leading to the redevelopment of the surrounding area through added retail and hospitality. The project included the full restoration of the existing Grade I listed station, incorporating the technical requirements of a transport interchange fit for the 21st century.

Throughout construction and restoration of this complicated scheme, London Midland connections were kept almost entirely operational with minimal inconvenience to both staff and passengers throughout the design. The result is a thoroughly modern transport interchange with over 45 million passengers passing through the zone every year. [48]

Shops and cafés occupy what was formerly a Victorian store for beer brewed in the Burton-on-Trent breweries. Within the Grade 1 listed building, The design of the undercroft exposed the original brick arches to the former beer vaults within new fully glazed shop fronts. Opening up the platform level to expose the undercroft revealed a naturally lit main concourse that acts as the main thoroughfare connecting different parts of the complex. The designers say that “the cafés and bars on the main concourse connect via escalators and lifts to the hotel and restaurants at the platform level, providing intuitive connectivity throughout the public areas.” [49]

Developments after the completion of HS1 and St. Pancras International illustrate just how rapid change has been over the years. They have included:

A. The East Coast Main Line Upgrade which began in 2019 and which includes:

- the construction of a new platform and track at Stevenage – which encompassed a 126 metre-long platform (featuring amenities like a passenger lift and ticket vending machines), and 2 km of new track, permitting more frequent services between Hertford and Stevenage North and which opened in August 2020;

- work at Werrington (North of Peterborough) to improve capacity and reliability of passenger services – a new two track line and tunnel separating freight and passenger movements and eliminating the delay caused by freight trains crossing the East Coast Main line;

- improvements to power supply infrastructure to enable the use of electric trains; and

- King’s Cross Expansion – renewing and expanding tracks, signalling and overhead equipment serving King’s Cross Station, particularly the reopening of the third tunnel (‘King’s Uncrossed’ – December 2020 – June 2021) enabling increased service frequency.

For the sake of completeness, Wikipedia also lists further major works to improve services on the East Coast Main Line which include: [44]

- Power supply enhancement on the diversionary Hertford Loop route;

- Re-quadrupling of the route between Huntingdon and Woodwalton (HW4T), which was rationalised in the 1980s during electrification (part of the ECML Connectivity programme);

- Enhanced passenger access to the platforms at Peterborough and Stevenage;

- Replacement of the flat crossing at Newark with a flyover;

- Upgrading of the Down Fast line at Shaftholme Junction from 100 mph to 125 mph and higher-speed associated crossovers (part of the ECML Connectivity programme);

- Modified north throat at York station to reduce congestion for services calling at platforms 9 – 11 (part of the ECML Connectivity programme);

- Freight loops between York and Darlington (part of the ECML Connectivity programme);

- Darlington station up fast line platform and future station remodelling as part of HS2;

- Fitment of TASS balises and gauging/structure works proposed by the open-access operator GNER (Alliance Rail) to enable tilt operation of Pendolino trains north of Darlington station, supporting its aspirations for express 3 hr 43 min London to Edinburgh services;

- Power supply upgrades (PSU) between Wood Green and Bawtry (Phase 1 – completed in September 2017) and Bawtry to Edinburgh (Phase 2), including installation of static frequency converter (Frequency changer) technology at Hambleton Junction and Marshall Meadows Bay area.

- Level-crossing closures between King’s Cross and Doncaster: As of July 2015 this will no longer be conducted as a single closure of 73 level crossings but will be conducted on a case-by case basis (for example, Abbots Ripton Level Crossing will close as part of the HW4T scheme)

- Increasing maximum speeds on the fast lines between Woolmer Green and Dalton-on-Tees up to 140 mph (225 km/h) in conjunction with the introduction of the InterCity Express Programme, level-crossing closures, ERTMS fitments, some overhead line ewuipment (OLE) rewiring and the OLE PSU – estimated to cost £1.3 billion (2014). This project is referred to as “L2E4” or London to Edinburgh (in) 4 Hours. L2E4 examined the operation of the IEP at 140 mph on the ECML and the sections of track which can be upgraded to permit this, together with the engineering and operational costs.

- In June 2020 it was reported that the UK government would provide £350 million to fund the UK’s first digital signalling system on a long-distance rail route. The signalling is to be fitted on a 100-mile (161 km) section of the East Coast Main Line between King’s Cross, London, and Lincolnshire, which will allow trains to run closer together and increase service frequency, speed and reliability. The first trains are expected to operate on the East Coast Main Line using this digital signalling technology by the end of 2025, with all improvements scheduled for completion by 2030. [45]

B. Upgrades to the Midland Main Line into St Pancras which were first proposed in 2012 as part of the High Level Output Specification for Control Period 5, to include electrification of the line between London and Sheffield, but paused in 2015 along with the rest of the HLOS plans in order to carry out a review. Work was restarted later in 2015, then cancelled again in 2017, and were finally re-announced in 2021 as part of the Integrated Rail Plan. [43: p24][46]

C. Rail and Tube service changes since 2000: various changes to the Rail and Tube services which call at King’s Cross and St Pancras over the past quarter century. As of November 2022, these changes included:

- Eurostar – 2007 – Services moved from Waterloo to St Pancras; 2015 – Introduced direct London-Lyon/Avignon/Marseille service in summer season; 2018 – 2 train per day London-Amsterdam service introduced; 2019 – Third daily service to Amsterdam introduced; 2020 – Direct Amsterdam-London services introduced;

- Southeastern High Speed – 2009 – Domestic HS1 services began; 2012 – Operated high speed ‘Javelin’ services between St Pancras and Stratford during London Olympics;

- East Midlands Railway – 2003 – 1 train/hour (tph) St Pancras-Manchester ‘Project Rio’ service introduced while WCML underwent engineering work (ended 2004); 2007 – East Midlands Trains franchise created, merging Midland Mainline and Central Trains; 2008 – 1 tph introduced to Corby; 2009 – 2 tph introduced to Sheffield by extending 1 tph London-Derby; 2019 – Franchise awarded to EMR;

- Thameslink – 2007 – Thameslink platforms open at St Pancras; 2009 – 15 tph peak hour service introduced on core section; 2018 – A large timetable change in May reintroduced cross-London services via London Bridge and many new services; 2019 – Cambridge-Brighton service doubled to 2 tph in each direction;

- London North Eastern Railway – Early 2000s – Increased Leeds services from 37 trains/day (tpd) to 53 tpd as Class 373s were moved to GNER; 2011 – ‘Eureka’ timetable change simplified stopping patterns and introduced 1 tpd London-Lincoln service; 2015 – VTEC awarded franchise; introduced daily services to Stirling and Sunderland; 2016 – Newcastle services extended to Edinburgh; 2018 – Franchise awarded to London North Eastern Railway (LNER); 2019 – ‘Azuma’ trains enter service; expanded service to Lincoln and Harrogate by extending existing services every other hour;

- Great Northern/Thameslink – 2007 – King’s Cross Thameslink station closes with through services moved to St Pancras; 2018 – Great Northern route connected to Thameslink, resulting in several services moving to St Pancras and continuing through London;

- Grand Central – 2007 – Services begin with 1 tpd London-Sunderland; 2008 – Introduced a 3 tpd service to Sunderland; 2009 – Introduced a 4th daily service to Sunderland; 2010 – Introduced 3 tpd between London and Bradford; 2012 – Added a 5th Sunderland service; 2013 – Added a 4th Bradford service;

- Hull Trains – 2000 – Services begin with 3 tpd London-Hull: 2002 – 4th daily service to Hull; 2004 – 5th daily service to Hull; 2005 – 6th daily service to Hull; 2006 – 7th daily service to Hull; 2015 – 1 tpd extended to Beverley; 2019 – 2nd daily service extended to Beverley;

- Lumo – 2021 – Service commenced;

- Tube – Circle – 2009 – Broke the ‘circle’ with extension to Hammersmith; 2014 – New S Stock trains;

- Tube – Hammersmith & City – 2012 – New S Stock trains

- Tube – Metropolitan – 2010 – New S Stock trains;