As I have shared this series of articles about Iranian Railways on the internet, I have been pointed to articles in Swedish, Danish and German which cover the early years of Iran’s Railway network….

Contributors to the SJK Postvagen (the forum of the Swedish Railway Club) have been particularly keen to share some of these. I have used Google Translate to create a first translation draft of each article and then sought to clarify anything unclear.

The articles and extracts below are of particular interest because they are written from the perspective of the time, rather than with the benefit of hindsight!

Here are the first three items:

The first is a short extract from an article which was originally written, I believe, in German in the Traffic Engineering Journal in 1933: [1]

A Trans-Persian Railway.

The Persian government has been working the construction of a railway across Persia from the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf for several years. Around 400 km of this line have already been completed at both ends. The remaining distance of about 1000 km is now to be tackled. The entire engineering work has been outsourced to two Danish companies and one Swedish company. The railway starts from the southern tip of the Caspian Sea. The Persian plateau is reached after about 100 km. There is only one major city along the route, Tehran, of course. At the southern end of the railway, the southern Iranian Zagros mountains are crossed. The Persian government intends to cover the estimated cost of RM 240 million from the normal state budget. The construction work is expected to take 6 years.

The second extract was originally written in Swedish. The contributor on SJK Postvagen provided only pictures. They are, however, intriguing. The notes associated with each picture are direct translations of the original notes: [2]

Locomotives in Persia

A Steam Locomotive from South Persian State Railways, built by Baldwin as Works No. 61670 in 1932. Note that the locomotive has short buffers and AAR coupler combined with screw coupler. Probably the locomotive was oil-fired because the ash box seems to be missing.

A Steam Locomotive from South Persian State Railways, built by Baldwin as Works No. 61670 in 1932. Note that the locomotive has short buffers and AAR coupler combined with screw coupler. Probably the locomotive was oil-fired because the ash box seems to be missing.

Iranian Railways locomotive made by Beyer Peacock.

Iranian Railways locomotive made by Beyer Peacock.

Iranian Railways 2-10-2 made in England after the Second World War.

Iranian Railways 2-10-2 made in England after the Second World War.

Iranian Railways oil-fired steam locomotive, built in America.

Iranian Railways oil-fired steam locomotive, built in America.

The pictures above have limited information associated with them. It is to be hoped that I can fill out details when I come to focus on the motive power on the Iranian Railway Network in a future article.

The third article is from a Danish source it is an Appendix containing a lecture by P. Swartling given at the Danish Engineering Federation on 17th March 1933.

Proceedings of the Danish Engineering Federation 1933: Appendix 2 – Page 19-31

P. Swartling: Railway Construction in Persia.

Persia was only in name a free country with a ruler who spent most of his life in Europe. It was completely in the hands of its neighbours, Russia in the North and Great Britain in the South.

In order to prevent Russia from stretching its tentacles down into India, it was in Britain’s interest not to expedite the development of communications in Persia. … The result has been that the country is now significantly behind in this regard. As late as 1918, cars and other motor vehicles were completely unknown in Persia to the greater part due to the lack of import provisions. The country’s topography also mitigated against the development of communications.

While much of the country is made up of a pasture. This is surrounded in the north By the Elburs Mountains and to the west and south by the no less imposing Zagross Mountains. The difficulties in advancing and building through these mighty mountain ranges have been too great.

In the spring of 1918, after the Brest-Litovsk peace deal, the Russians withdrew their troops from Persia. An example of the difference this made to the British occupation of Persia was that they were forced to build a road from Kanakin (Iraq) on the Persian border across the Zagross Mountains to Hamadan to enhance the already existing road to Baku, previously built by the Russians. At the same time, British forces were busy building a road from the port city of Bushir to the town of Shiras, located about 1000 metres above sea level. From Shiras, one can access the other larger cities in southern Persia such as Kerman, Yezd and Ispahan without too much difficulty.

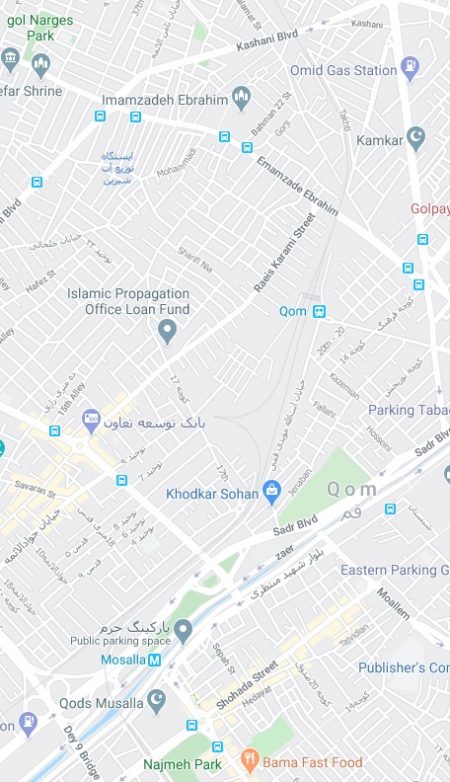

Map of Persia with its surrounding states.

Map of Persia with its surrounding states.

Talard Valley in the neighbourhood of Pol-e-sefid

Talard Valley in the neighbourhood of Pol-e-sefid

As a result, wagons and cars flooded into Persia, giving an impetus to interest in them. The now reigning Shah, Riza Kahn Pahlevi, who ascended the throne after the revolution in 1925, is very interested in the development of communications. In the relatively short time he has been in power, these have progressed rapidly.

According to reports, at the end of 1930 there was a network consisting of about 1950 km first class routes, 9500 km second class and 2200 km third class routes, all accessible by motor vehicles all year round. These figures clearly show that development has moved quickly.

The ruling Shah has a burning interest not just in roads, but perhaps to a still greater extent in railways. One of his first acts after his accession in 1925 was also to introduce a tax on tea and sugar, the yield of which is intended to be used entirely for railway purposes. This tax amounts to about 20 million kroner a year and has even in 1932 brought in about 100 million kroner of investment of which 60 million has already been spent.

Before I focus on the construction company on the present project, I want to touch on some previous projects. An important issue just before the war was the construction of a route running west to east, which would link India with Europe. It should have been an extension of the so-called Baghdad railway. However, with the outbreak of the World War, these plans were completely shelved.

During the war, England, which is in charge of the neighboring country of Iraq, built some railways in that country, and in 1919 the Basra — Baghdad — Kanakin line was opened at the Persian border. A continuation of this line into Persian territory across Kermanska — Hamadan to Tehran then became possible. Of course, this project has great advantages. Using an existing route, it would cross the Zagross Mountains at one of their lowest points. The line would to a large extent follow the traffic route that was already used, and thus go through neighbourhoods with some human settlements. As an advantage, the existing oil canals at Kanakin can also be accessed, which could mean cheap rail costs.

Vreskdalen, whose steep rock walls will in the future be joined by an iron-arch bridge 120m above the valley floor.

Vreskdalen, whose steep rock walls will in the future be joined by an iron-arch bridge 120m above the valley floor.

However, the project has a very big disadvantage, as the railway would not end at a port within the borders of Persia, but in a port owned by another nation, which if relations sour could have unforeseen consequences.

Another proposal has the same disadvantages – a line from Tebris (Tabriz) to Trebizond (Trabzon) at the Black Sea.

It was believed, and probably with reason, that no project is satisfactory, which does not end at a port – a sea-port located in the Persian territory and under the control of the Persian state. The line, which is now under construction, fulfils this requirement and should largely be a good solution to Persia’s communication problems. The line will connect the Caspian Sea with the Persian Gulf and thus cross the entire country and so has been named The Trans-Persia Railway. It is about 1450 km long and has been estimated to cost about 500 million pounds.

From Bender Shapur port on the Persian Gulf, the railway route ascends along the Karun River, crosses it with an 1100 metre long viaduct at Ahvas and continues up to the city of Disful. This route of nearly 300 km is completed and is currently operated by two trains a week. From Disful, the railway begins to meander up into the high Zagross Mountains. This is the first length of the work under American leadership under the auspices of the Persian state. The ongoing route has yet to be finally determined. One option is to connect Hamadan-Kaswin to Tehran, alternatively, a more direct route may be followed. The direct route saves approximately 70 km of travel but loses the advantage of passing two large cities. The longer route is preferable.

The so-called ‘north line’ from the Caspian Sea to Tehran starts at the port of Bender Shah, situated on the Caspian Sea about 20 km east of the city of Bender Guez. A test track from Bender Shah to Shahi, about 130 km in length was completed by a German consortium with Julius Berger as the main stakeholder, and this part also operates in traffic with two trains a week in each direction. The remaining line, from Shahi to Tehran, is about 300 km long and is being constructed by a Swedish company. The work was started in the winter of 1932 with Captain Ragnar Sjodahl as work manager.

The Abbasabad valley as seen from the future Kirnveig line.

The Abbasabad valley as seen from the future Kirnveig line.

Shahi is at the foot of the Elburs Moutains and the railway route must run through these to Tehran. This mighty mountain range’s lowest pass is at an altitude of 2200 metres above sea level. Once this point is passed, the line descends in a narrow valley down to Binnekou, after which the line can be completed without difficulty through the countryside to Tehran, which is at a height of 1200 metres above sea-level.

The German syndicate which built the Bender Shah – Shahi line provided complete proposals for the entire Shahi – Tehran route. For the so-called north ramp (nordrampen), the uphill slope of the Elburs Mountains up to the tunnel under the pass, two alternatives were established. The first, which was fully developed, was based on a maximum grade of 2% with a minimum curve radius of 300 metres. The second, which was not fully developed, was based on a maximum grade of 3% and with the lowest curve radius of 220 metres. The line in general was based on a maximum rise of 1.5% and minimum curve radius of 300 metres.

As the north ramp will be one of the most interesting railway routes, I will focus more closely on this part of the line. It follows the Shahi Talar River valley up into the mountains, but because the river rises significantly in its upper course, considerably more so than a railway could accommodate, the line meanders from side to side to reach sufficient height to reach the pass tunnel at Gaduk. The German syndicate, in its suggested alternatives, provided an ingenious route using the side valley of the Talar – specifically the Shurmast and the Delilam valleys.

The most serious issue with these proposals is that these side valleys lie quite far down from the pass tunnel. The line will almost certainly, as a result, runs at a considerable height above the Talar Valley floor 600-700 metres! This entails high construction costs. In addition, the side valleys chosen show signs of relatively recent or old landslides and so must be completely avoided.

It was clear that new proposals had to be drawn up and the aforementioned valleys completely avoided. Furthermore, we adopted the principle of following the valley floor as long as possible. When this was no longer feasible, due to the steep slope of the valley floor, we used spirals and tunnels, etc. to gain sufficient height above the valley floor. The line will always lie in the valley floor except when when the terrain is easier to climb higher up on the lateral slopes of the valley. Furthermore, costs are kept to a minimum and the transport of all building materials will be more economic.

The most important issue, a question that obviously has the biggest consequences for the future of railway traffic, was the determination of the maximum grade. The only fully prepared proposal was based on a maximum increase of 2%, which is not steep enough to for such a pronounce rollercoaster of a journey.

A significantly steeper ascent should be used. …. A gradient at least as steep as used in Central Europe which has much higher traffic flows should be considered. A gradient steeper than for example, the one at the Gotthard Railway (2.7%) or the one at the Arlberg Railway (3.14%) should therefore be justified.

In this context, it may be appropriate to mention, as a comparison, that the highest altitude of Persian Railway at Gaduk (2050 metres above sea level) is almost twice as high as the highest point of Gotthard Railway (1150 meters above sea level). For our main proposed route, we intended a maximum grade of 3.2%, but cost comparison purposes, we considered alternatives based on a range of maximum gradients between 2.5% and 4%.

Theoretically, one can calculate the most suitable maximum gradient if one fixes a certain amount of freight to be transported, and determines the rolling stock to be used. The latter can be done but would be rather difficult to make assumptions about the future amount of goods.

Professor Blum has, in an investigation found in the Verkehrtechnische Woche, vintage 1930, concluded that the largest increase of 35% would be the most suitable. He compiles two curves, one constituting the variable operating costs for different gradients, and the other line costs for different gradients, where in the line costs are assumed to be interest and amortization of the construction costs, track maintenance and transported freight costs.

Before we were able to complete this interesting investigation of the best maximum gradient. Hans Maj. Shahen fixed the maximum gradient at 2.8%. I believe that a steeper gradient would have been feasible and therefore acceptable.

The choice of the minimum permissible radius of curvature is governed by impact on construction costs. Due to the development of technology, it is clear that one should be able to make use of a significantly smaller radius of curvature than for example used on the approximately 50-year-old Gotthard Railway (Gotthardbahn – between Switzeralnd and Italy), where curves of 280 metres radius were used. At stations, point curvature is fixed at a radius of 160 metres. Of course, a larger radius must be allowed on the line between stations. On the Trans-Persia Railway, the minimum radius of curvature has been fixed to 220 metres, although 200 metres can also be defended, and even less could be defended, for instance as used on the Semmering Railway (Semmeringbahn – in Austria) which has a minimum radius fixed at 190 metres.

The distance between the stations on the line is about 15 km, but between each station there is a rest area with 0.25% slope, which may later be converted to a station site.

We generally use the process of staking/fencing the route to allow for mapping of the planned route. After general observation by the human eye a provisional line is determined approximately in the position of the future railway. Angles and lengths are measured and fixed with stakes. By using a tachymeter or possibly with phototheodolite, the terrain is measured on each side of the line and a map is drawn.

The route of the line is then more firmly determined and the ground cover removed. The staking/fencing of the line was led by the engineer Harry Hacklin, who remained on site throughout the work on the northern gradient into the mountains. The work is of utmost importance and demanding.

Under Hacklin’s leadership two survey teams of six men and one staking/fencing team were at work. Maps were made at a scale of 1:1000, contours were set at one or two metres but on steep ground the contours were set at 5 metres.

An insignificant offset of the line sideways on a level map with 5 metre contours can have a significant effect on the line’s position. Many times adjustments to the line as shown on paper had to be carried out in the difficult terrain at the time of fencing , before the line was handed over for construction.

En-route from Sbahi to the tunnel at the head of the pass at Gaduk, the railway continued to follow the Talar river. As far as Pol-e-Sefid 560km from Bender Shah, the line is in the valley bottom with a maximum rise of 15%. From Pol-e-Sefid, where a locomotive station is planned, the line rises at 28% with a reduction for curves and tunnels. Through a change in the Talar Valley, the line travels on the valley floor to Sorkhabad. Here the real difficulties start. From this point the river valley climbs steeply to the pass at Gaduk – a stretch of 12 km – with a rise of 1:15. Since the railway has to rise by no more than 1:40, the line has to deviate significantly to achieve the necessary gain in height. Two alternatives were considered for this stretch of the line. The first – the spiral proposal – required 5 spirals and two tunnels. The second – the ‘lacet’ proposal – required the line to be laid in long loops. … The latter proposal will probably come to fruition because of its cheaper construction costs.

As staking/fencing progressed, we were urged to make an immediate start on construction work.

The whole stretch from Shahi to Tehran was divided into 4 building sections 5 or 6 parts each. The length between Shahi and Gaduk was divided into 2 sections of 65 and 45 km length. The first section, which was divided into 5 parts, was in progress along its full length when I left Persia in November last year.

Of the whole second building section, only two parts had started by that time. The workforce was between 8000 and 9000 men, but will almost be doubled if the program for building the northern track in 5 years is to be met.

That it was not an easy task to organize and get started on this work should be pretty clear when one considers that contracts were let to a series of sub-contractors and the company had to direct their work.

Even if the start was difficult, you can easily see that the continued construction work will not be easier. I want to express the hope that the new Swedish leadership will succeed in completing the work expeditiously and that Persia will gain the hoped for benefits of the railway route.

References

- The reference information for this extract was provided in German: Verkehrstechn. Zeitschr 1933: N.B., on https://www.postvagnen.com/sjk-forum/showthread.php/12693-Irans-Järnvägar/page2, accessed on 3rd April 2020.

- No specific reference information was provided on SJK Postvagen: https://www.postvagnen.com/sjk-forum/showthread.php/12693-Irans-Järnvägar/page2, accessed on 3rd April 2020.

- The reference information for this lecture was provided in Danish: Swartling var då han skrev nedanstående vid BJ. Troligen var han senare SJ Distriktschef i Giiteborg. Jårnvågsbyggnader i Persien. (Foredrag av gyste byråingenjiiren P. Swartling vid Ingenibrsfiirbundets extra måle den 17 inars 1933.) p19 Bilaga 2., on https://www.postvagnen.com/sjk-forum/showthread.php/12693-Irans-Järnvägar, accessed on 2nd April 2020.

To finish this article here are three further pictures. The first is adjacent to this text and shows another of the locomotives used on the line and displayed on a plinth in Rey, (c) Alireza Javaheri, used under a Creative Commons Licence. [18]

To finish this article here are three further pictures. The first is adjacent to this text and shows another of the locomotives used on the line and displayed on a plinth in Rey, (c) Alireza Javaheri, used under a Creative Commons Licence. [18]