The featured image above is a photograph of Saint Felicien Railway Station in 1959. [9]

In the North of Québec, some 300 miles from Montreal, there is an area of extensive mining – deposits of copper, zinc, gold and cobalt wee being mined in the mid-20th century. In the first half of the 21st century, Northern Quebec’s mining sector is a significant part of the province’s economy, focusing on gold, nickel, lithium, graphite, iron, and copper, focusing on gold, nickel, lithium, graphite, iron, and copper, with major operations like Glencore’s Raglan (nickel) and Agnico Eagle‘s Canadian Malartic (gold) leading the way, alongside emerging lithium projects in the James Bay region, leveraging Quebec’s hydropower for cleaner operations and creating jobs in remote areas like Nunavik, despite logistical and environmental challenges.

Raglan Mine is, today, a large nickel mining complex in the Nunavik region of northern Quebec. “It is located approximately 100 kilometres (62 miles) south of Deception Bay. Discovery of the deposits is credited to Murray Edmund Watts in 1931 or 1932. It is owned and operated by Glencore Canada Corporation. The mine site is located in sub-arctic permafrost of the Cape Smith Belt, with an average underground temperature of −15 °C (5 °F).” [1]

In 2025, the mining complex “is served by and operates the Kattiniq/Donaldson Airport, which is 10 nautical miles (19 km; 12 miles) east of the principal mine site. There is a gravel road leading from the mine site to the seaport in Deception Bay. It is the only road of any distance in the province north of the 55th parallel. As the complex is remote from even the region’s Inuit communities, workers must lodge at the mine site, typically for weeks at a time. From the mine site employees are flown to Val D’or, or in the case of Inuit employees, their home community. Ore produced from the mine is milled on-site then trucked 100 km (62 mi) to Deception Bay. From Deception Bay the concentrate is sent via cargo ship during the short shipping season (even by ice breaker it is only accessible 8 months of the year) to Quebec City, and then via rail to be smelted at Glencore’s facilities in Falconbridge, Ontario. Following smelting in Ontario, the concentrate is sent back to Quebec City via rail, loaded onto a ship and sent to the Glencore Nikkelverk in Kristiansand, Norway to be refined.” [1]

Agnico Eagle’s Canadian Malartic is, in 2025, one of Canada’s largest gold mines, located in Quebec’s Abitibi region, transitioning from open-pit to a major underground operation (Odyssey Mine) to extend its life, with Agnico Eagle becoming sole owner in 2023 after acquiring Yamana Gold’s share. This significant asset is a cornerstone of Agnico’s Abitibi operations, aiming for long-term value through expansion and exploration, supporting regional growth. [2]

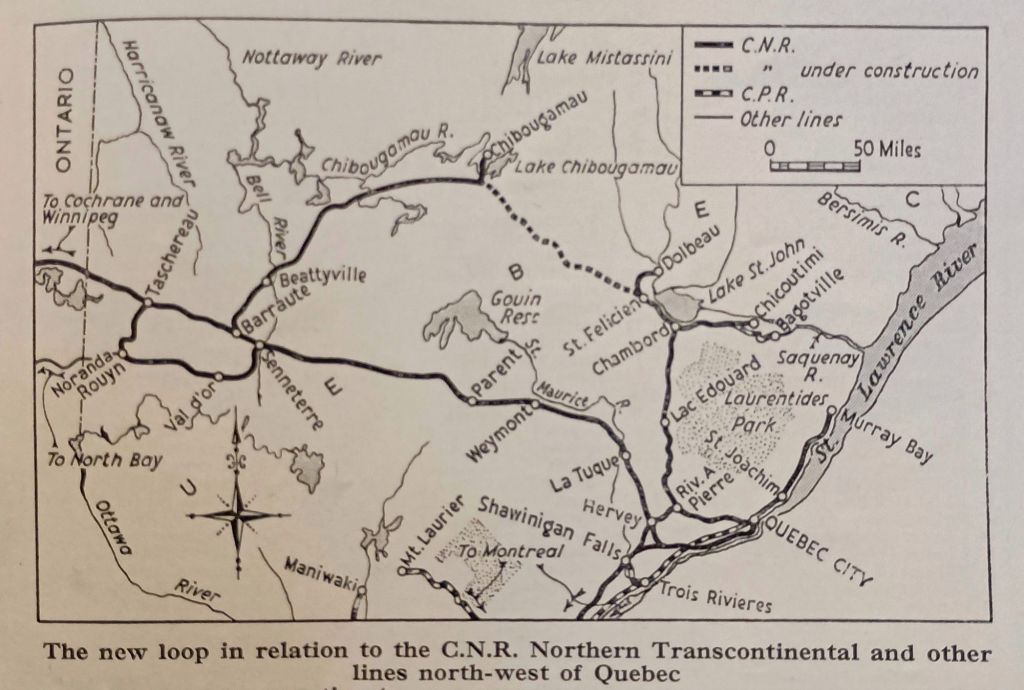

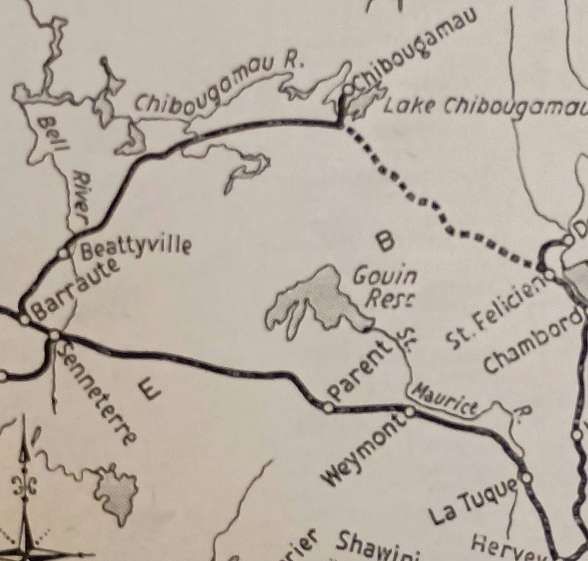

Canadian National Railways were authorised to open up northern Québec by a Bill passed in the Canadian Parliament in 1954. The resulting Act approved the construction of two new lines. “One line was to run from Beattyville to Chibougamau, a distance of 161 miles, and the other for 133 miles from St. Felicien to a junction near Chibougamau with the line from Beattyville.” [3: p201]

Beattyville to Chibougamau – Construction

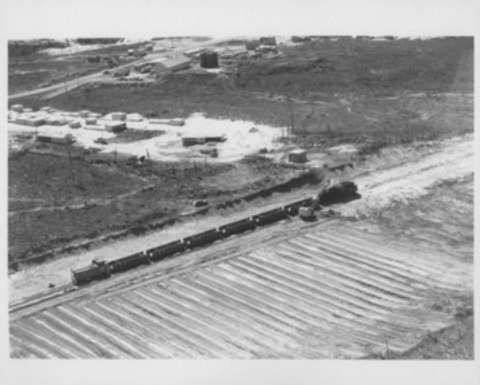

“The line to Beattyville provided a direct route from the rich mining area around Chibougamau to the ore smelting plant at Noranda, some 250 miles west of the Quebec-Ontario border, and its construction was undertaken without delay. Work started in November, 1954, and the railway was completed in November, 1957, to Beattyville, where it joined the existing 39-mile branch from Barraute, on the CNR northern transcontinental route.” [3: p201] It appears below as a solid line on the extract from the map above. [3: p203]

The engineering work (ground, earthworks, drainage and bridge substructures) for the railway between Beattyville and Chibougamau was contracted in two separate contracts: Beattyville to Bachelor Lake and Bachelor Lake to Chibougamau. Trackwork was laid by railway staff and comprised 85-lb. rails on creosoted sleepers, ballasted with gravel obtained from local deposits along the route. Construction presented significant challenges, “arising primarily from the climate and the ‘muskeg’ [bog]. During the long winters, temperatures fell to -95 deg. F., or 63 deg. C below zero, and blizzards were frequent. In summer, 90 deg. F. was common, and the attacks of the vicious black-fly were devastating. Work on the ‘muskeg’ resulted in the formation in the first instance, and later in lengths of newly-laid track disappearing without trace into the treacherous bog. All these conditions made transport and the movement of heavy mechanical equipment exceedingly difficult at different times, and the flies and extremes of temperature were most trying for those engaged on the works.” [3: p202]

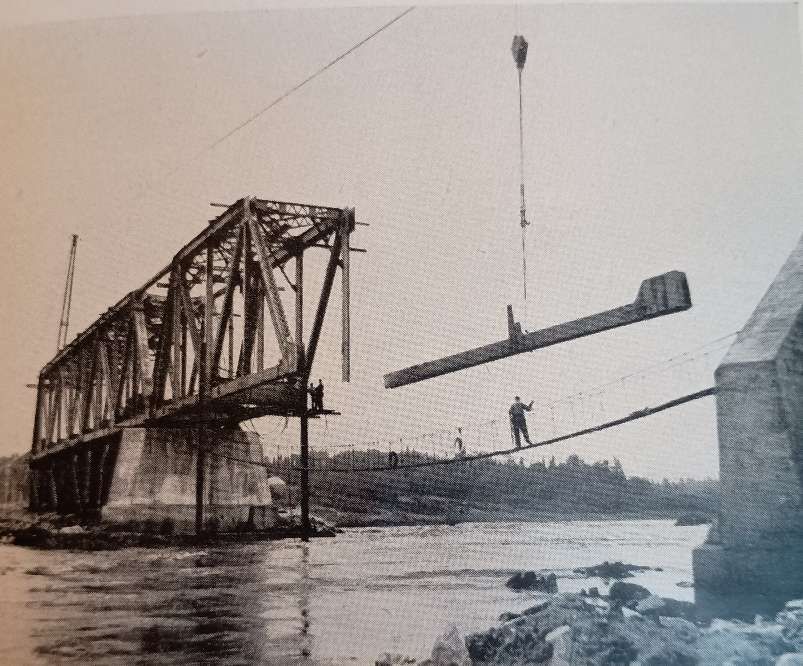

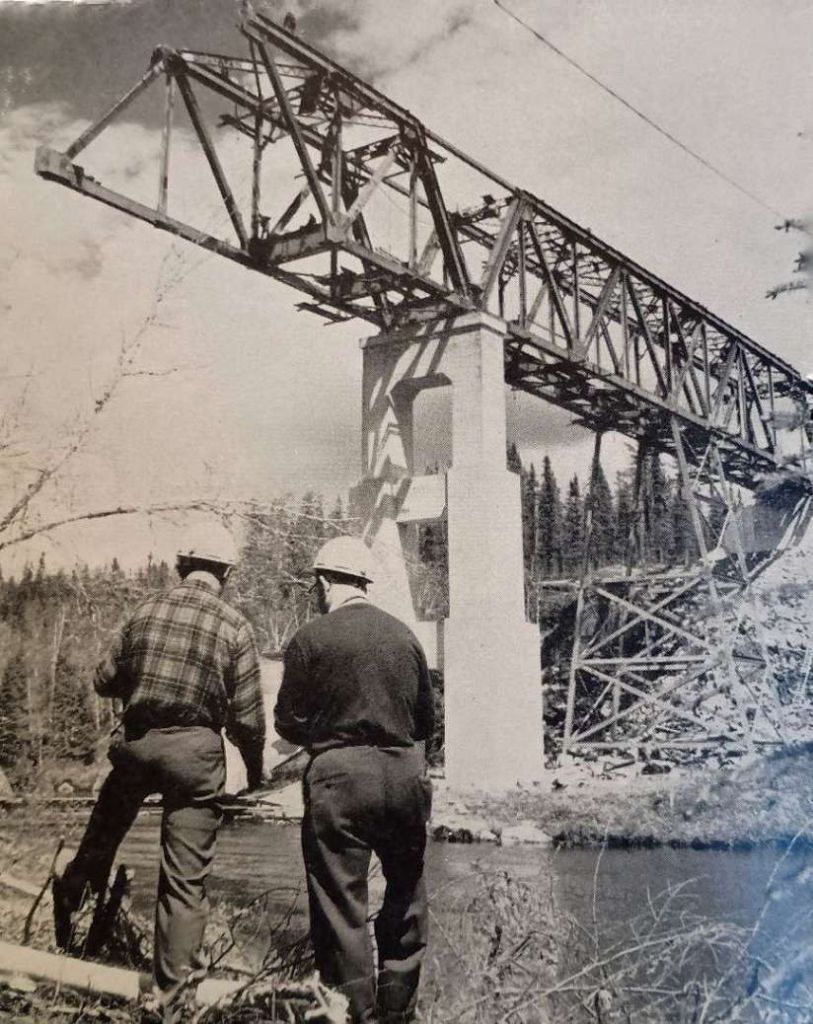

The Railway Magazine article highlights work on the Bell River bridge. …

The site chosen for the Bell River Bridge was “at the head of Kiask Falls Rapids where the normally-broad Bell River [was] only 200 ft. wide in its main channel and 25 ft. deep; when the water level [was] high, the velocity of the current [was] over 25 m.p.h. The river banks and bed [were] of solid rock, and the concrete abutments and pier [were] founded on it. The western span [was] over the main stream, the eastern being across the shallow part of the river. The trusses were designed to have a roadway cantilevered out from them.” [3: p203]

Although the most difficult to construct, the Bell River Bridge was not the only important structure on the line. The article cited the crossing of the Chibougamau River which “required three spans of 100 ft. each; the first bridge over Opamica Lake ha[d] one span of 90 ft. and two of 45 ft.; and the second bridge ha[d] one span of 200 ft. and two of 45 ft.” [3: p206]

St. Felicien to Chibougamau – Construction

The line from St. Félicien was begun in September, 1955, and was due for completion at the end of 1959. “Except for the first 15 easy miles out of St. Félicien, it passes through considerably rougher country than does the route from Beattyville. It joins that line at a point known as Chibougamau Lake, or Coche Lake, a few miles from Chibougamau.” [3: p206]

Here again “the clearing of the ground, the formation earthwork, and the drain-age were carried out by contract in two sections (1) the first 66 miles from St. Félicien, and (2) the remaining 67 miles to the junction with the line from Beattyville. On the first section, the formation ha[d] been completed [by early 1959], and about 50 miles of permanent way and bridge work [were also] finished. The contract for the second section was not let until 1957.” [3: p206]

Lighter rail (80-lb.) was used on the first 40 miles of the line from St. Felicien, with 85-lb. rails used on the remainder of the route. “The ruling gradient was “1 in 80 and the sharpest curvature about 22 chains. There [were] 14 bridges with single spans up to 196 ft. 10 in., some of considerable height. Construction was plagued by the same difficulties as the line between Beattyville and Chibougamau. In addition, the route required the excavation of deep cuttings and construction of high embankments.

“The first bridge on the line [was] over the Salmon River, less than two miles from St. Félicien. It consist[ed] of two through-type plate-girder spans each of 100 ft. The substructure, built by contract – in common with six other bridges in the first 66 miles – was begun with a coffer-dam for the pier, with the intention of founding it on the rock river bed. It was then found that this rock was of in-sufficient thickness for that purpose and rested on sand. Accordingly, 35-ft. sheet-piling was driven to enable concrete foundations to be constructed.” [3: p206]

At the time that The Railway Magazine article was being written, it noted that “The largest bridge is being built to – span the Cran River Ravine, which has a bottom-width of 400 ft. and a depth of 100 ft. Two 196 ft. 10 in. spans are being used, and the pier is 96 ft. in height above normal water level. Here again, the river is fast-flowing, and a cableway 1,200 ft. long between supports 140 ft. high was erected for the construction. It had a capacity of seven tons. The pier was built in the form of three superimposed arches each 30-36 ft. high. The cantilever trusses of the bridge are nearly 100 ft. above the river.” [3: p206]

“Of the other 12 bridges, one [had] one span of 196 ft. 10 in. and two of 75 ft.; another [had] two spans of 100 ft.; and several [had] 90-ft. spans of the plate-girder type. The considerably more numerous bridges, and the rougher terrain, on the railway from St. Félicien … inevitably made progress less rapid than on the line from Beattyville.” [3: p206]

A Possible Northward Extension

Work was started on a northern extension from Chibougamau but the anticipated traffic on the lines South of Chibougamau did not occur. North of Chibougamau civil engineering work was undertaken but rails were never laid. There remains a visible, overgrown route with a built bridge over the Stain River that’s now only accessible by river or the old railway formation itself. This unfinished project, built for accessing northern mineral wealth in the mid-20th century, remains a testament to early northern development, with its earth embankment and bridge still visible as a “green road” through the forest, despite being washed out in places.

To see something of this abandoned line, please follow this link. [4]

Operation

Concentrated ore was the main commodity being transported by the CN Railroad from Chibougamau followed by lumber and by-products of lumber transformation such as wood chips used to make paper.

However, from the end of the 1980’s, mining operations declined in the Chibougamau region with a resulting drop in the demand for rail transport and a loss of income for the CN.

The Line in the 21st Century

Investigation of the line in the 21st century is hampered by the climate conditions in the area. Google Streetview has limited access to the area and much of what can be provided is of snowbound images with little sign that a railway is in use.

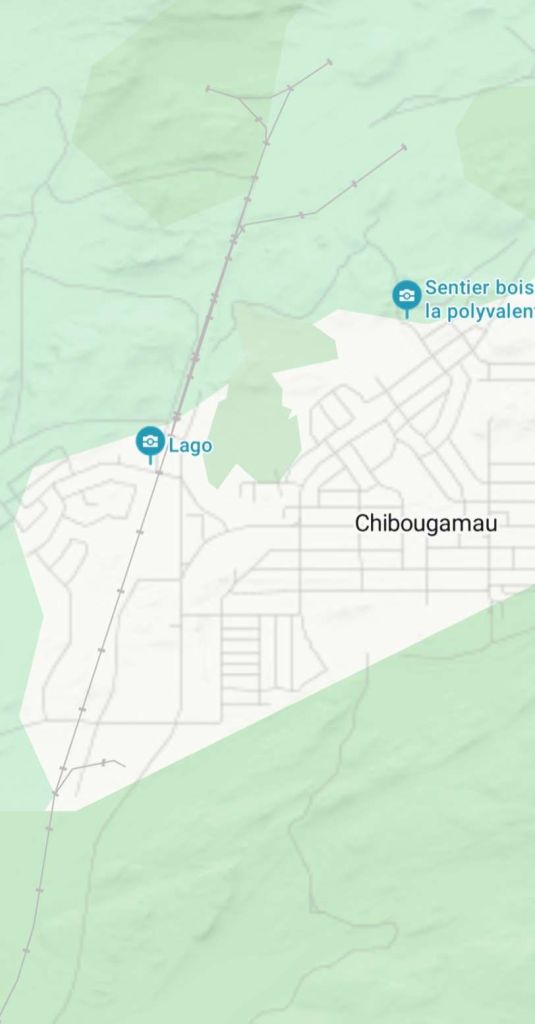

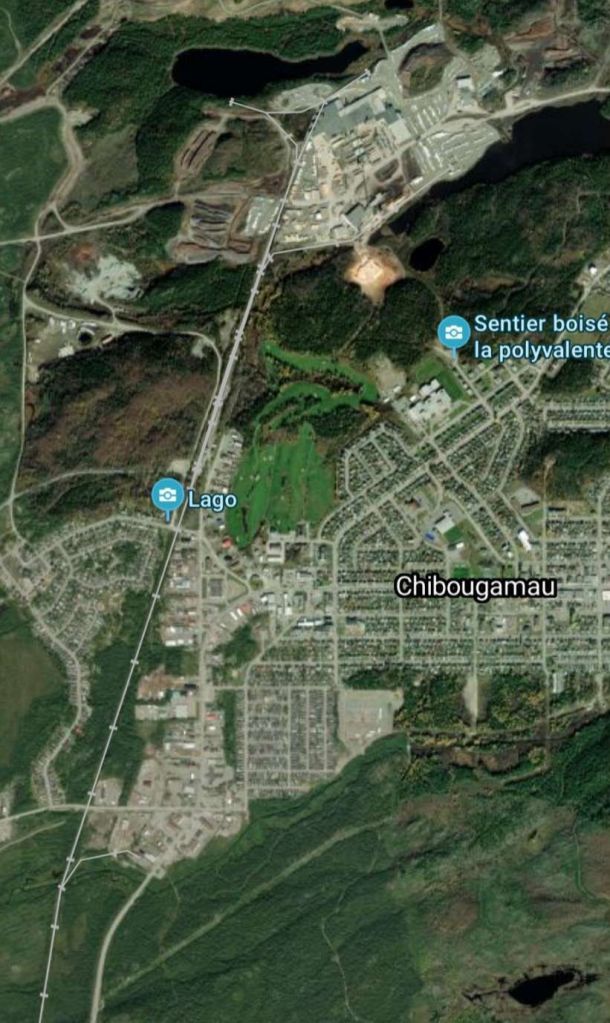

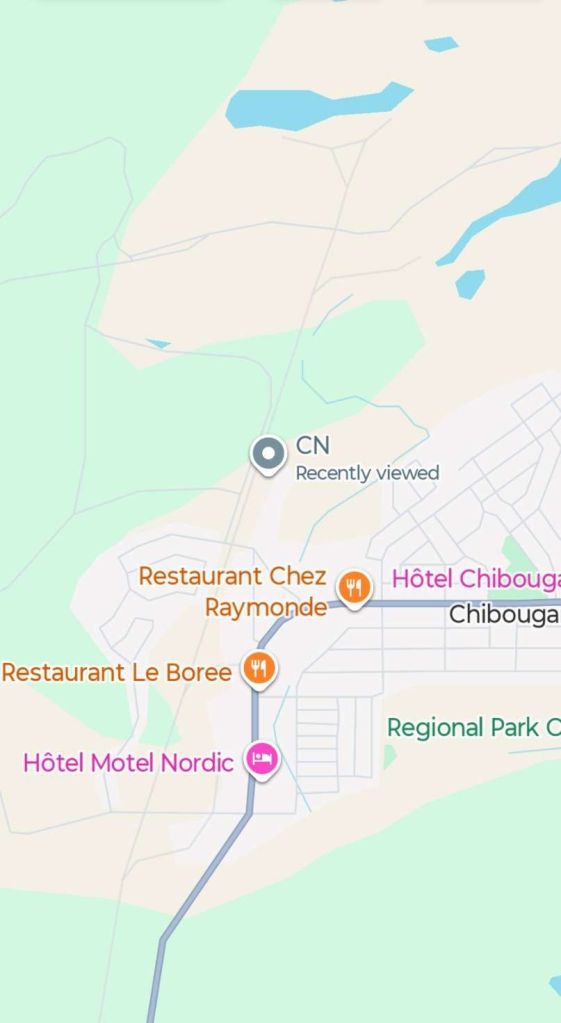

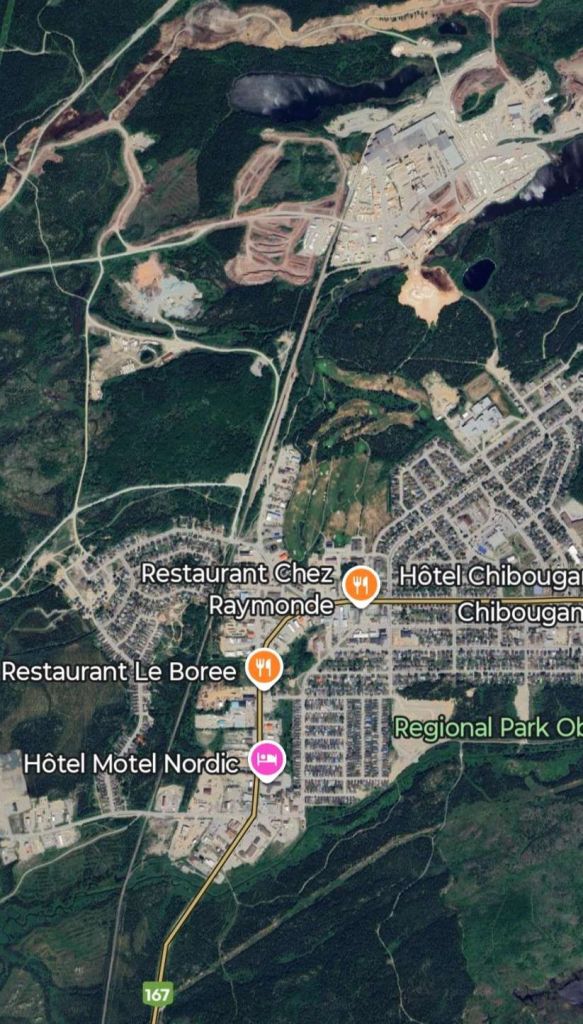

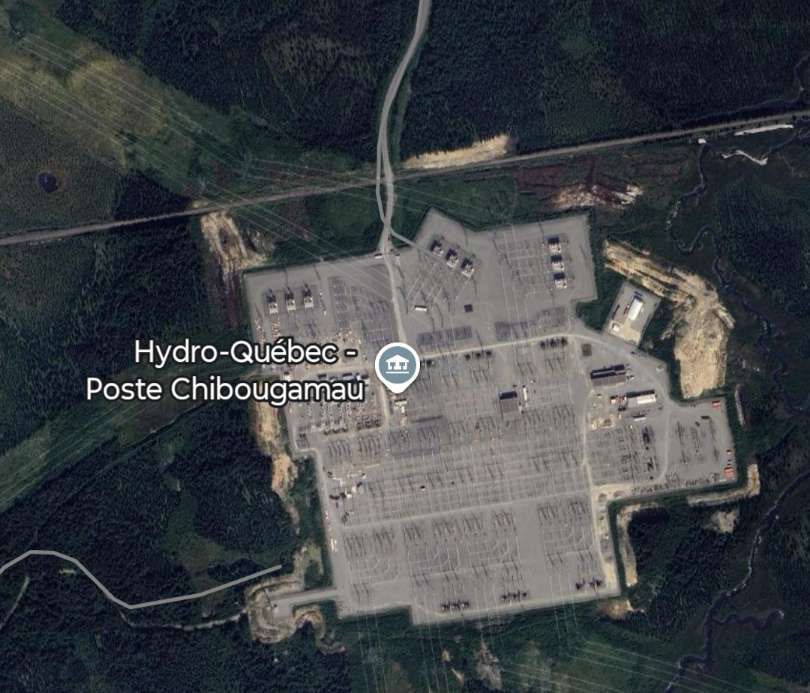

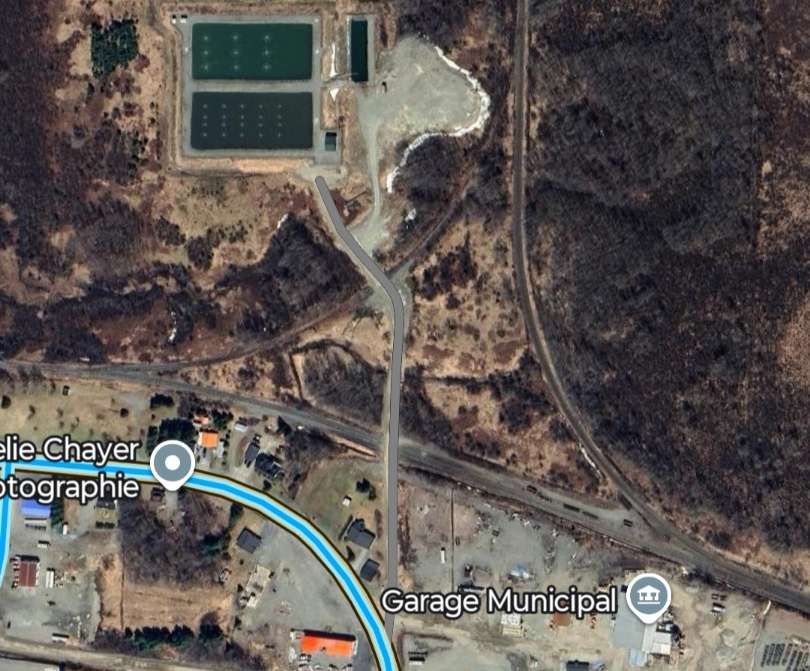

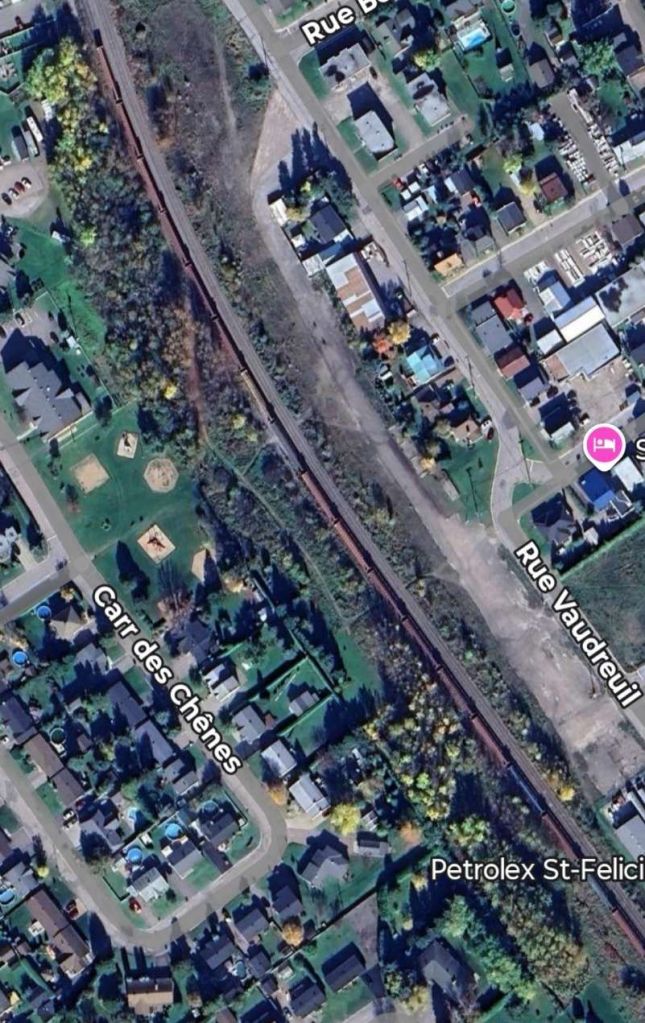

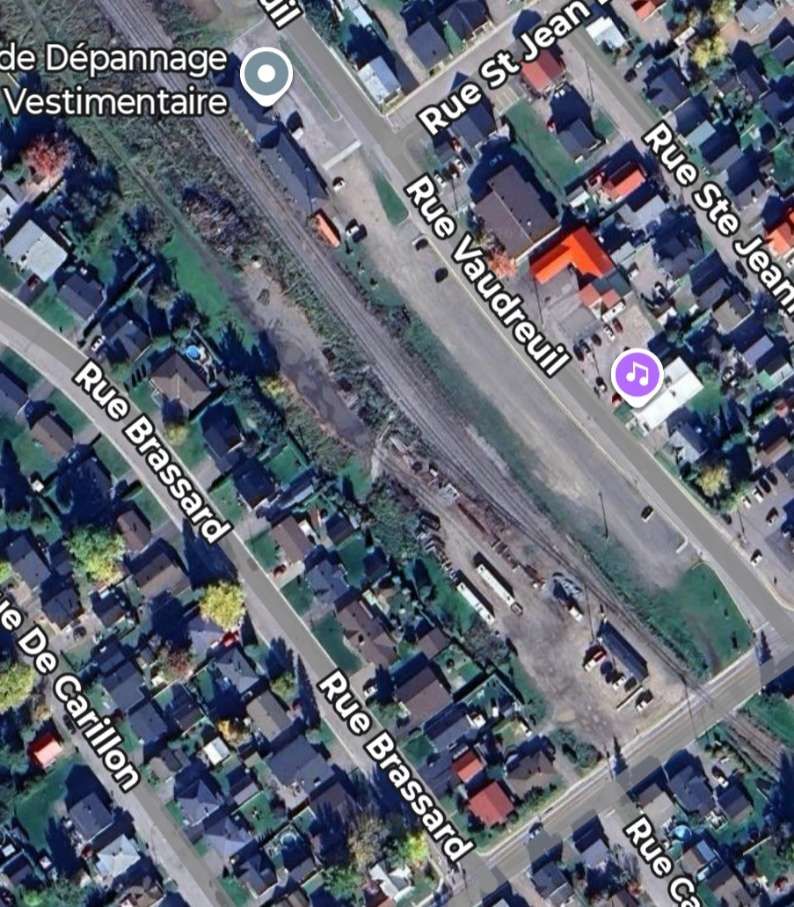

Bing and Google Maps imagery showing the area around the railhead at Chibougamau are reproduced below.

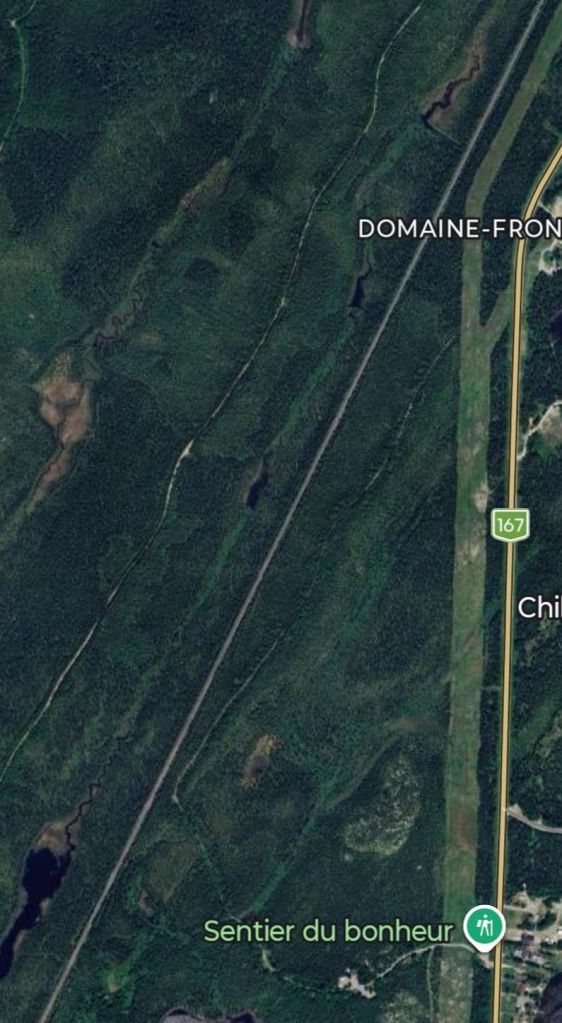

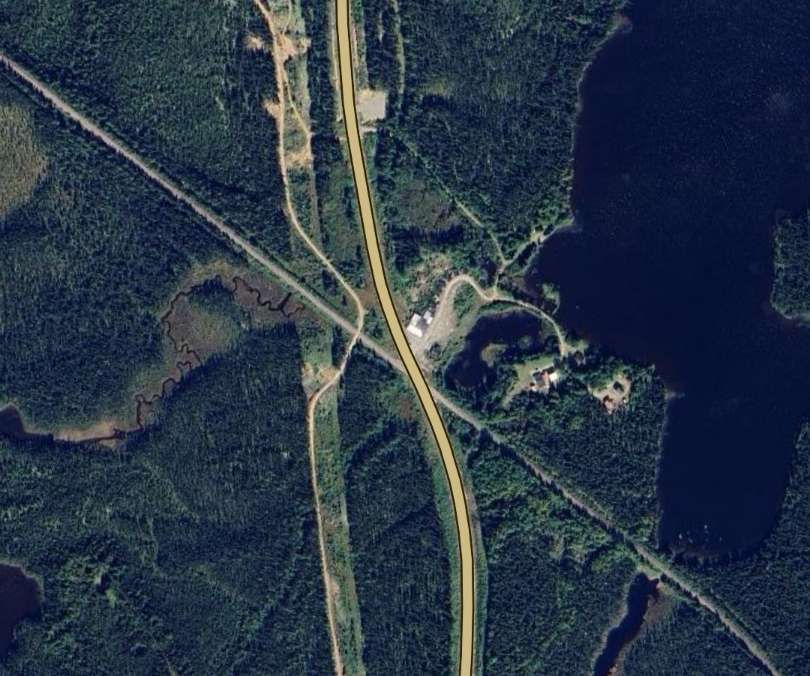

The next five Google Maps satellite images show the length of the line as far as the junction where the routes to Beattyville and St. Felicien diverge. ….

The location and river are named after George-Barthélemy Faribault (1789–1866). He was a prominent Quebec-born librarian, historian, and archivist known for his extensive collection of Canadian historical documents. The Faribault River flows East towards James Bay. [5]

From Faribault the line to Beattyville and Barraute turns West and runs close to the QC113. …

The line from Faribault to Barraute

Five further satellite images follow the route. Occasionally the line comes close enough to the highway to be seen looking South from the road.

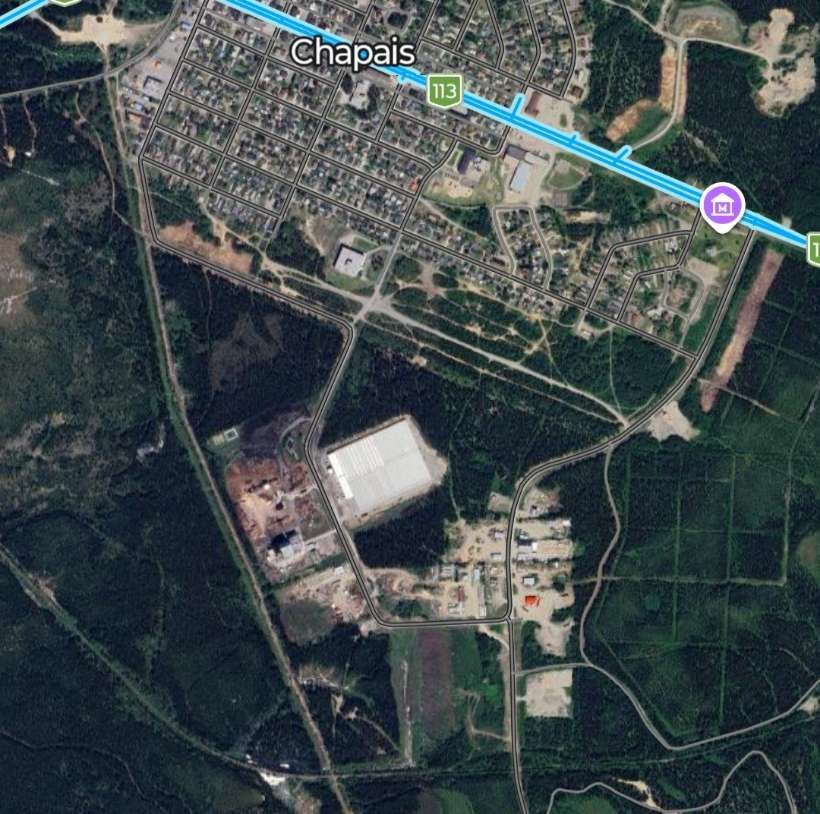

Barrette-Chapais is both the largest sawmill complex in Quebec and the largest forest management authority in Quebec.

Its facilities include a yard, a sawmill, a planing mill, a thermal power plant, and wood kilns. A wide range of wood products for the construction, energy, and pulp and paper sectors are manufactured there and then distributed in Canada and internationally. It employs 350 people throughout the full year. [6]

Barrette-Chapais provides comprehensive planning, management, and supervision of its forestry operations. The team plans harvesting, land access, and infrastructure alignment with environmental considerations to supply its sawmill complex . A significant amount of management and logistical work is carried out year-round. There are 150 workers in the field with 5 forest camps. [6]

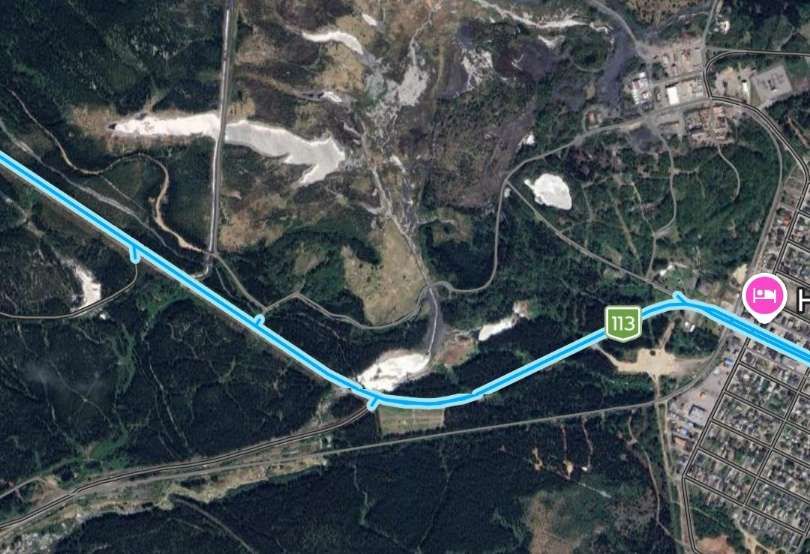

Continuing to the West, the line runs to the South of the township of Chapais.

Somewhere along this length of the old railway the rails disappear, probably having been lifted to allow vehicular use of the formation. The old line continued Southwest alongside the Chemin du Lac Cavan. …

A branch from the main line (also now lifted) appears to have run into Chapais.

As we have already noted, the main line of the railway ran alongside Chemin du Lac Cavan before it passed to the North of Lac Cavan. ….

The route of the old line heads West-southwest into the forested wilderness, passing to the South of Lac Beauchesne, then some distance to the North of Lac O’Melia.

It ran South of Lac Kitty and Lac Ford the line ran along the North shore of Lac du Calumet.

Then it ran to the South of Lac Hancock, to the North of both Lac Eleanor and Lac Barbeau.

Some distance to the South of Lac Mandarino and Lac Cady the line ran closer to the North shore of a body of water that appears to be unnamed on Google Maps, before being found on the South side of part of Lac Father.

The line continued to the North of Lac Relique and between two arms of Lac Father before bridging Lac Father at a point where the width of the channel was relatively limited, before then running along the North shore of another arm of Lac Father. After which it ran on the South side of another arm of Lac Father.

Continuing in a westerly direction the line eventually passes to the South of Lac Bachelor

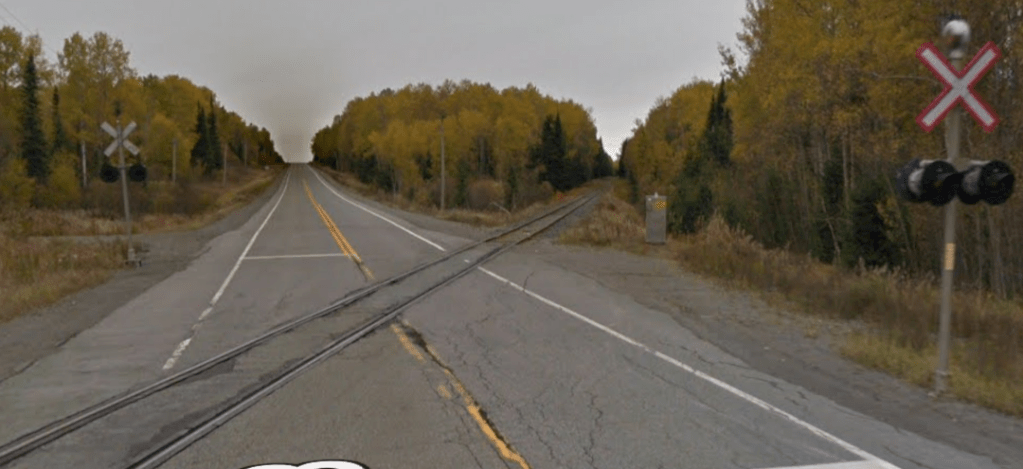

Near Goeland, the line crossed the QC113 again. …

The old line ran on, passing South of Lac Waswanipi, heading generally towards the Southwest.

At Miquelon, the route of the railway crossed the QC113 again. …

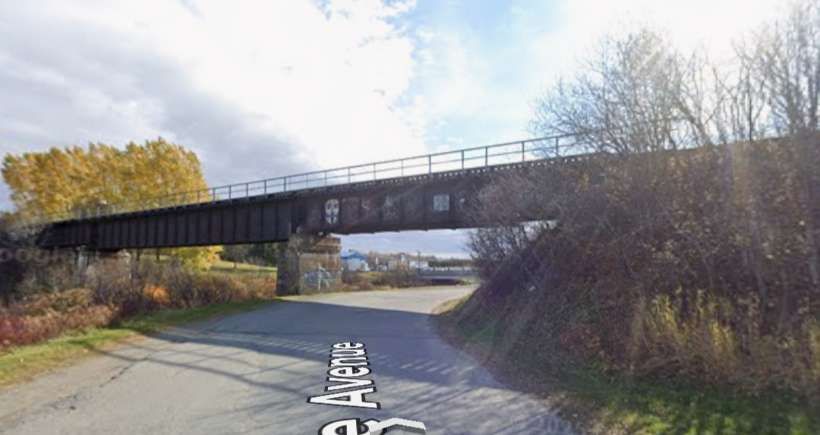

The same railway bridge, seen at track level in 2011, © Frédérick Durandxiii. [12]

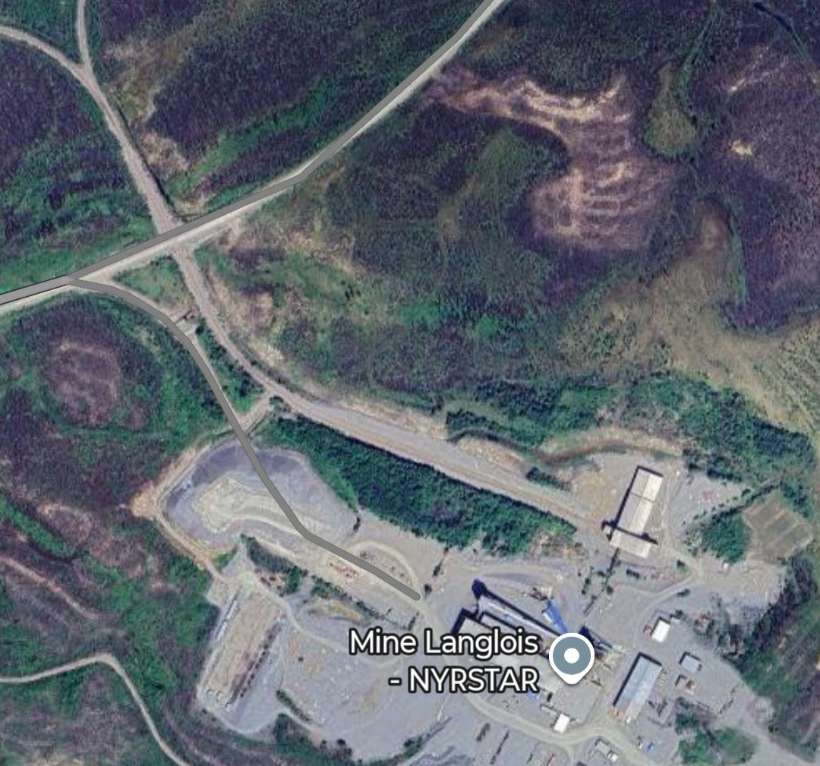

The old line continued Southwest, passing Southeast of Lac Burger. Then, through Grevet where Google Maps appears to show at least remnants of the old railway. Just to the Southwest of which, Google Maps shows a triangular junction providing access to a rail head associated with ‘Mine Langlois (NYRSTAR)’

NYRSTAR is a leading international manufacturer of Zinc. Its headquarters are in The Netherlands. The Langlois Mine seems to have stopped production late in 2019. [7] As of February 2026, the rail infrastructure seems to still be in place.

It seems as though the line to the Southwest of Grevet was in regular use while Langlois Mine was operational. The rails remain in place in the third decade of the 21st century.

Another triangular junction is visible on Google Maps at Franquet. …

The line heading West from the triangular junction above continues West for some distance. It crosses the QC113 and Route 1055 before reaching Les Rapides de l’Ile and Comporte.

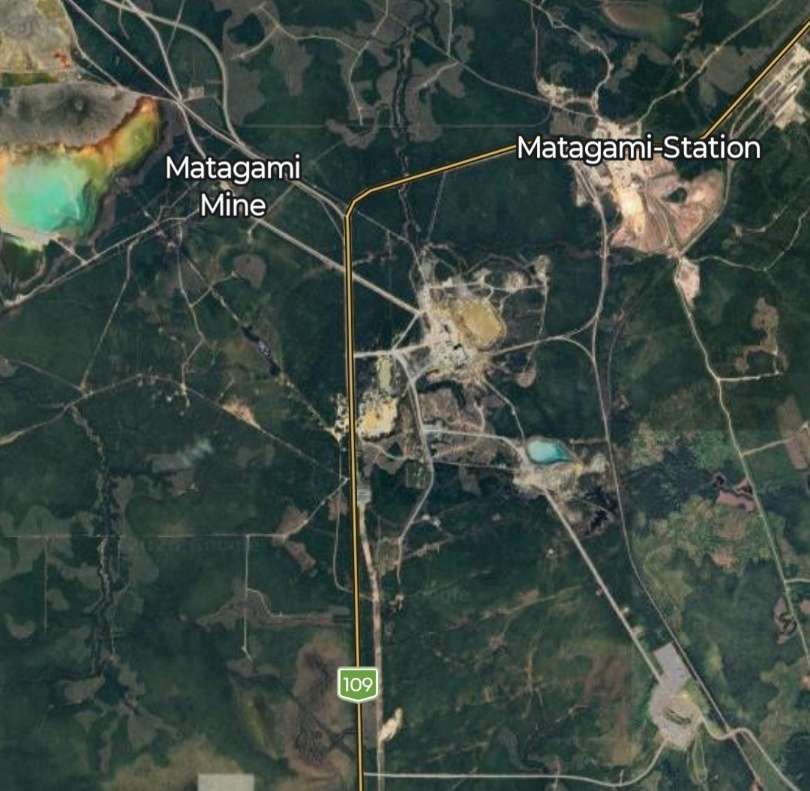

Beyond Comporte, the line gives rail access to mines close to Matagami. The mines were to the South and West of the township.

Returning to Franquet, we continue South-southwest along the line towards Beattyville and Barraute.

The line passes to the Southeast of Île Kâmicikamak and passes to the Southeast of Quevillon and its nearby ‘Hydro-Quebec – Poste Lebel’.

Continuing Southwest the line bridges the Riviere Bell.

Further South and West the line crosses the QC113 again. …

Further South, the remains of a turning triangle are visible on satellite imagery at Laas. …

The line continues South and West, passing to the North and then West of Lac Despinassy.

It is only a very short distance to the next road crossing. …

The next road crossing is at CH Des 1 & 2 Rang. …

The line continues in a South-southwest direction crossing a number of roads which did not warrant the use of the Google Streetview camera – 6th & 7th Rang E, Rang 4th & 5th East, Rang 3rd & 4th East. Although for the last of these a distant view of the level-crossing is possible.

We are closing in on the township of Barraute now. I have not been able to identify the location of Beattyville on Google Maps.

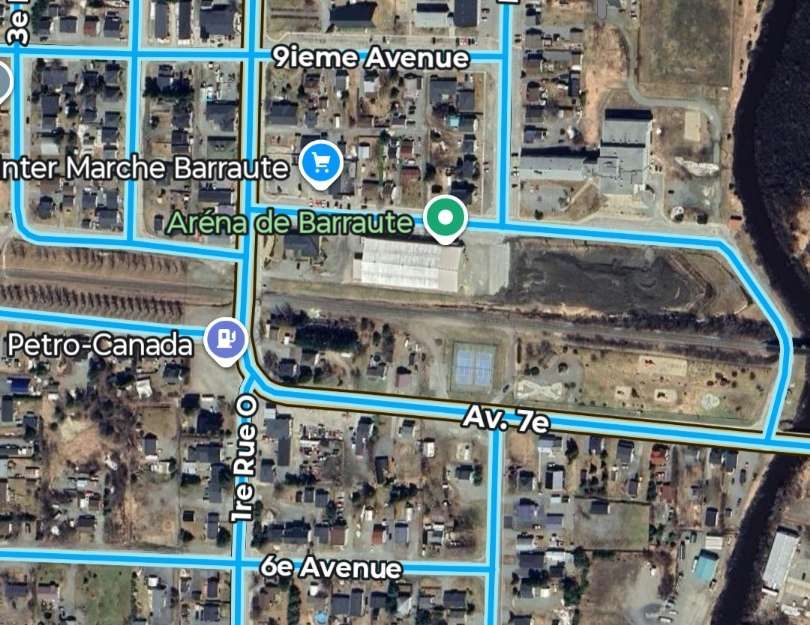

The next two photographs show the East-West line through the Centre of Barraute.

Having travelled all the way to Barraute, we now return to the junction South of Chibougamau (at Faribault).

The line from Faribault to St. Felicien

We are back at Faribault and taking the line to the East from the junction. ….

The line meets the QC167 at a level-crossing close to the South end of Lac Gabrielle, bridging the River South of Lac Gabrielle just to the East of the QC167. …

The line turns to the South and for a short distance runs parallel to both the QC167 and the River Chibougamau before bridging the river via a lattice girder bridge. …

A short distance further Southeast the line crosses a dirt road, Chemin du Domain Rustique at a level-crossing. …

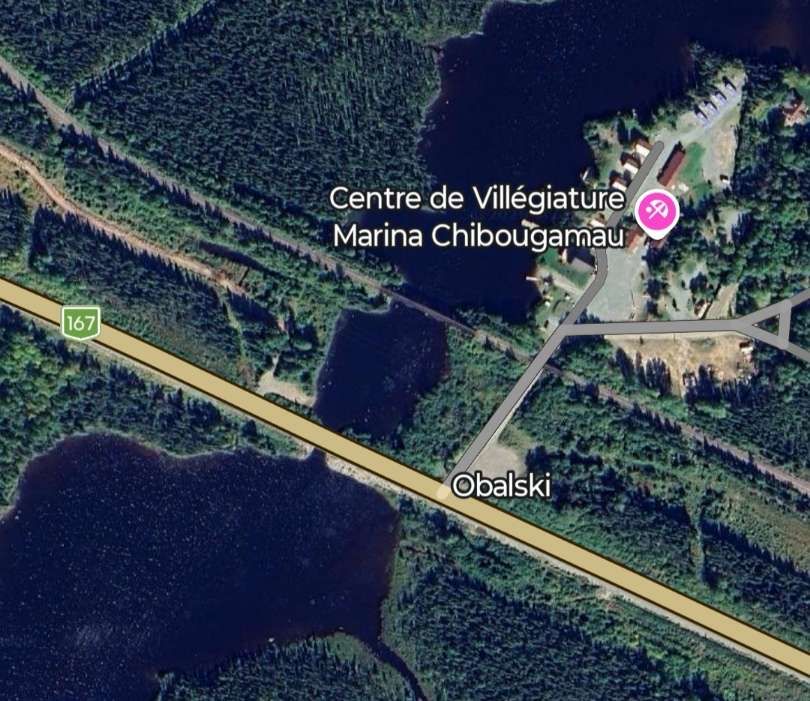

At Obalski, close to the Chibougamau Marina, the line bridges and arm of Lac Chibougamau

The railway heads on into the wilderness, first to the East-southeast, then to the Southeast, to the South and to the South-southeast passing to the East of a body of water not named on Google Maps, then between two further unnamed lakes.

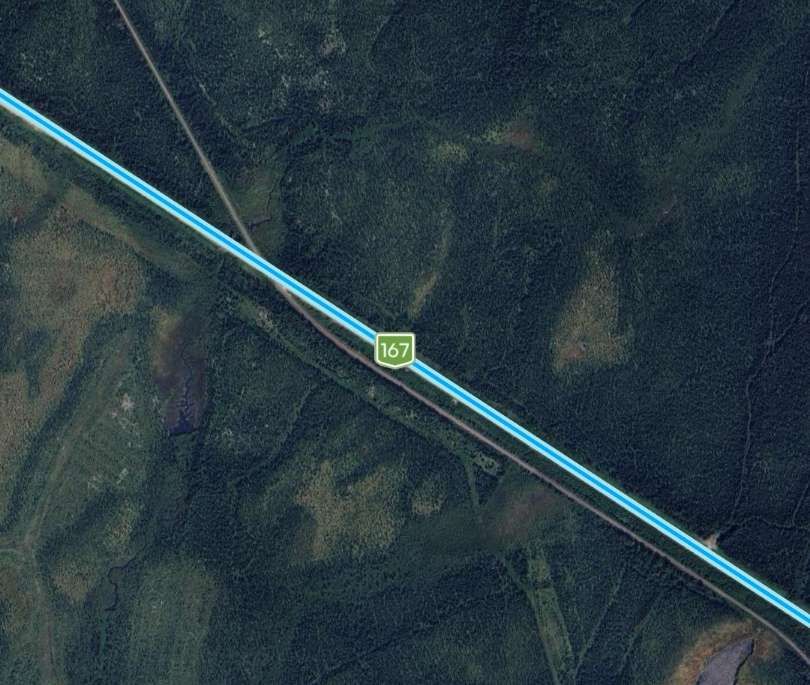

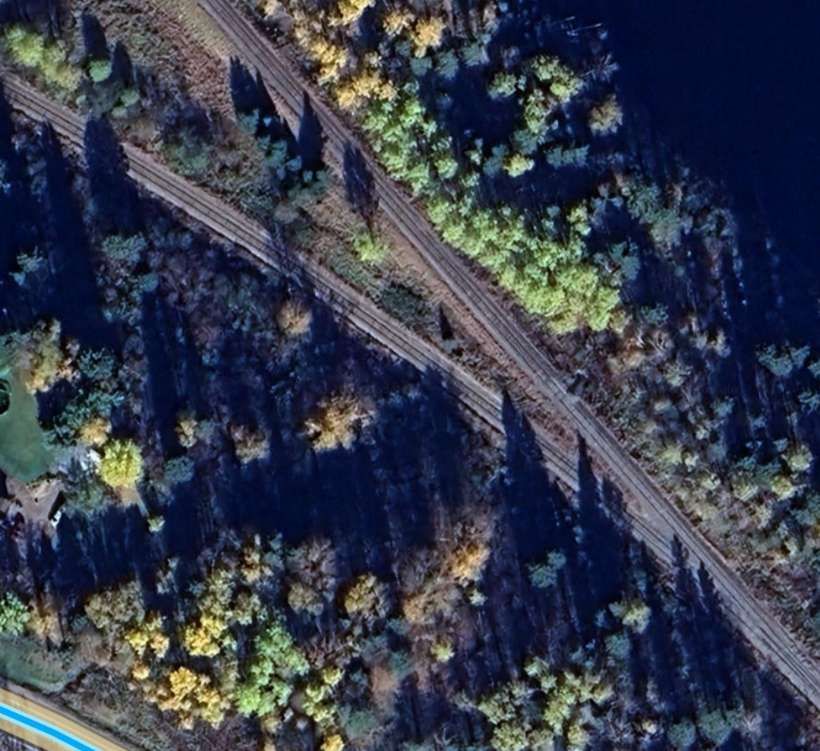

The line runs South-southeast on the East side of Lac Dufresne and then to the West of Lac Blondin before crossing the QC167 again and then running alongside it as far as Lac Malo.

Further South the line bridges the River Biosvert near Lac Charron. …

The line continues South on the East side of Lac la Blanche, before running parallel to the QC167 again, although not easily seen from the road because of the density of the vegetation.

Road and railway then cross the Coquille River and run down the East side of Lac Nicabau.

The railway continues to run Southeast at varying distances from the QC167 running to the North of Lac Ducharme and on through land dotted with a myriad of lakes of different sizes before once again taking close order with the QC167 to the Northwest of Lac Chigoubiche. It then runs down the Northeast flank of the lake continuing to follow relatively closely, the QC167. Indeed running immediately adjacent to it on one occasion. …

Beyond this, the line runs directly alongside Lac de la Loutre. Some considerable distance further along the line it passes under the QC167.

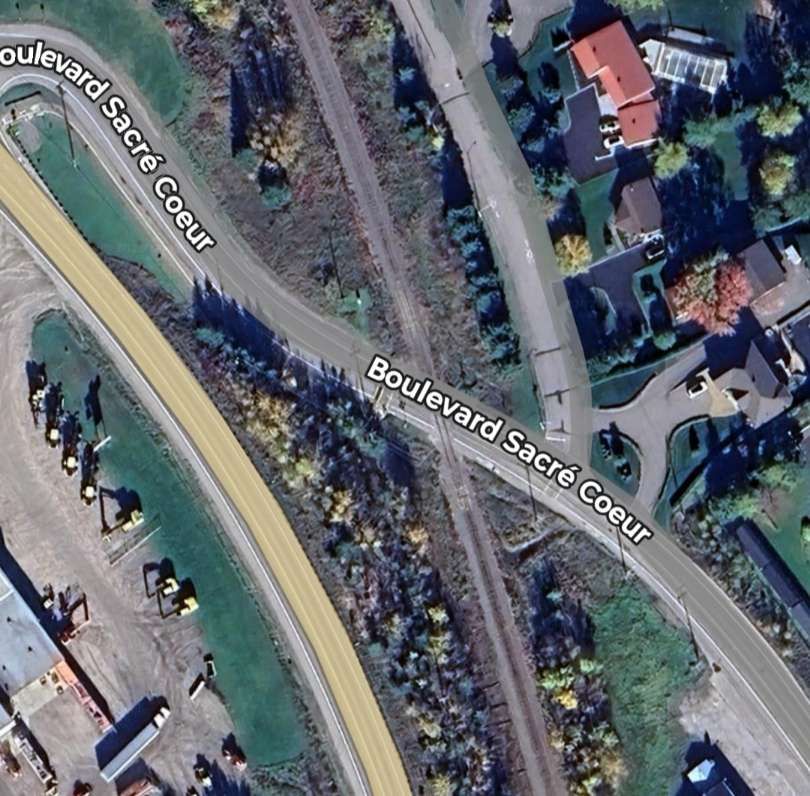

We are now approaching St. Felicien. The next road crossed is Rang Riviere Sub Saumons.

The line continues alongside the Riviere Ashuapmushuan into Saint-Felicien. …

Saint Felicien

In 1911, the government expropriated land under the Indian Act, permitting the James Bay & Eastern Railway the necessary ground for the railway to join Roberval to Saint-Félicien. [10]

We have already seen above that the line from Saint Felicien to Chibougamau was under construction in the late 1950s.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raglan_Mine, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- https://www.agnicoeagle.com/English/news-and-media/news-releases/news-details/2023/AGNICO-EAGLE-PROVIDES-UPDATE-ON-CANADIAN-MALARTIC-COMPLEX-INTERNAL-STUDY-DEMONSTRATES-IMPROVED-VALUE-EXTENDS-MINE-LIFE-AND-SUPPORTS-POTENTIAL-FUTURE-PRODUCTION-GROWTH-IN-THE-ABITIBI-GREENSTONE-BELT-POSITIVE-EXPLORATION-RESULTS-EXP-06-20-2023/default.aspx, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- New Railways in Quebec; in The Railway Magazine, Tothill Press, London, March 1959, p201-203 & 206.

- https://youtu.be/PARUga_1gEo?si=awPp6uPkG0LoI-0e, accessed on 1st January 2026.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George-Barth%C3%A9lemy_Faribault, accessed on 8th February 2026.

- https://barrettechapais.com, accessed on 8th February 2026.

- https://news.metal.com/newscontent/100981335-The-Langlois-zinc-mine-owned-by-Nyrstar-will-stop-production-in-December-Last-year-zinc-concentrate-production-reached-24000-tons, accessed on 9th February 2026.

- https://minedocs.com/17/Langlois_Fact_Sheet_072017.pdf, accessed on 9th February 2026.

- https://canada-rail.com/quebec/s/saintfelicien.html, accessed on 11th February 2026.

- https://baladodiscovery.com/circuits/734/poi/8137/railway, accessed on 11th February 2026.

- https://perspective.usherbrooke.ca/bilan/quebec/evenements/1150, accessed on 11th February 2026.

- https://www.frrandp.com/2021/01/canadian-national-railways-chapais.html, accessed on 11th February 2026.

- https://todayinrailroadhistory.com/cn-st-felicien-chibougamau-line-1959, accessed on 11th February 2026.