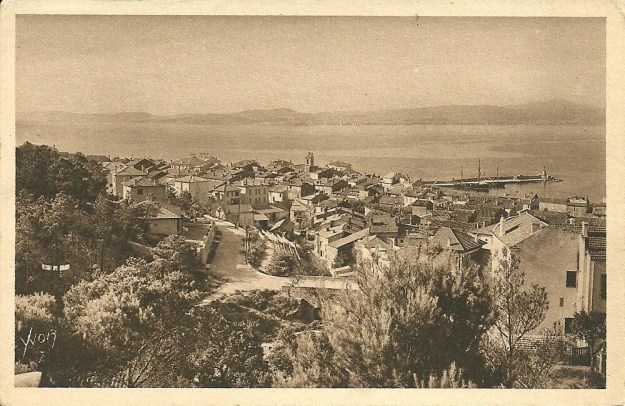

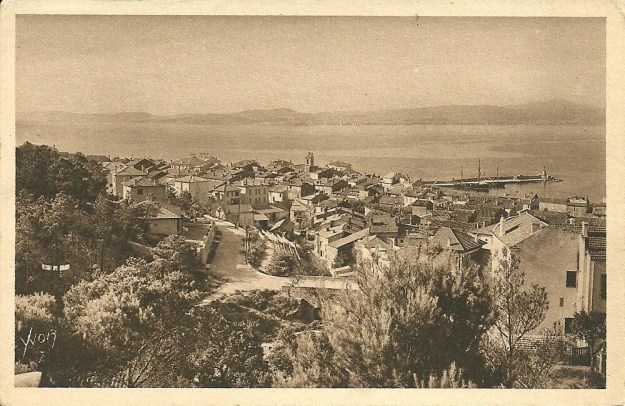

The small town of Sainte-Maxime [5] is south facing, at the northern shore of the Gulf of Saint-Tropez. In the north, the Massif des Maures mountain range protects it from cold winds of the Mistral. Sainte Maxime was founded around 1000 AD by Monks from the Lérins Islands outside Cannes. They built a monastery and named the village after one of the Saints of their order – Maxime.

The small town of Sainte-Maxime [5] is south facing, at the northern shore of the Gulf of Saint-Tropez. In the north, the Massif des Maures mountain range protects it from cold winds of the Mistral. Sainte Maxime was founded around 1000 AD by Monks from the Lérins Islands outside Cannes. They built a monastery and named the village after one of the Saints of their order – Maxime.

Fishing was the mainstay for the inhabitants, but during the early 19th century increasing amounts of lumber, cork, olive oil and wine was shipped to Marseilles and to Italy. The village grew and in the 20th century it started to attract artists, poets and writers who enjoyed the climate, the beautiful surroundings and the azure blue water.

In front of the old town you find the characteristic tower – La Tour Carrée – built by the monks in the early 16th century to protect the village from invaders. With an addition of a battery of cannons and with the Tour du Portalet in Saint Tropez the whole bay was protected. As late as in the beginning of the 19th century, Napoleon ordered a restoration of the battery while also adding cannons on the Lérins Islands. The tower is now a museum.

In front of the old town you find the characteristic tower – La Tour Carrée – built by the monks in the early 16th century to protect the village from invaders. With an addition of a battery of cannons and with the Tour du Portalet in Saint Tropez the whole bay was protected. As late as in the beginning of the 19th century, Napoleon ordered a restoration of the battery while also adding cannons on the Lérins Islands. The tower is now a museum.

On 15th August 1944, the beach of Sainte Maxime was at the centre of Operation Dragoon, the invasion and liberation of the Southern France during World War II. “Attack Force Delta”, based around the 45th Division, landed at Sainte Maxime. There was fierce “house to house” fighting before the Germans were decimated and eventually surrendered. By the foot of the Harbour pier and by La Garonette Beach there are memorials at the respective landing places honouring the US troops. The beach at Sainte-Maxime in 1938. The new road bridge is visible in the top right of the picture. This scene would change dramatically over the next few years and ultimately this would be one on the invasion beaches in 1944.

The beach at Sainte-Maxime in 1938. The new road bridge is visible in the top right of the picture. This scene would change dramatically over the next few years and ultimately this would be one on the invasion beaches in 1944.

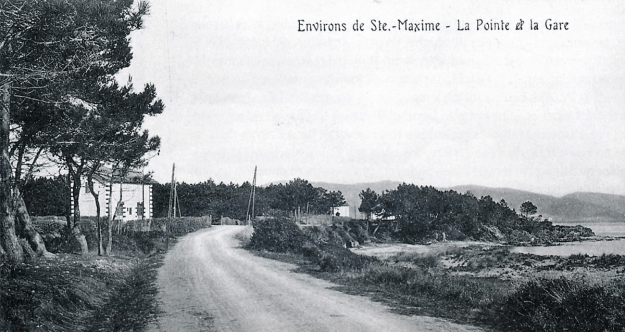

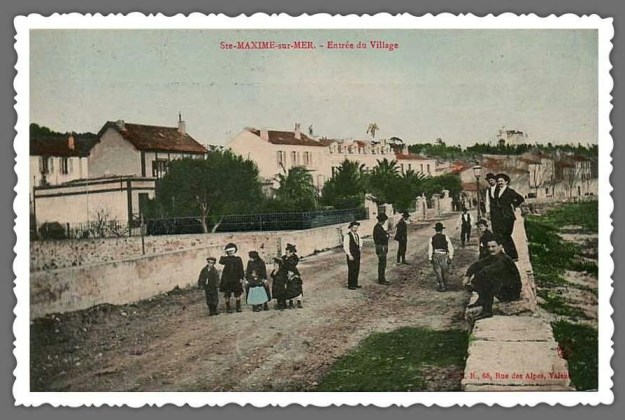

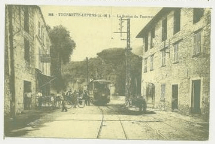

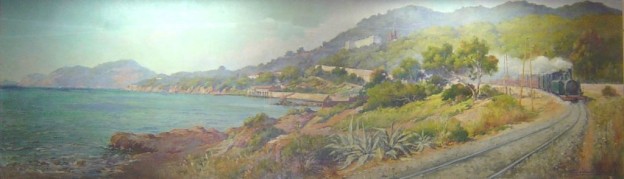

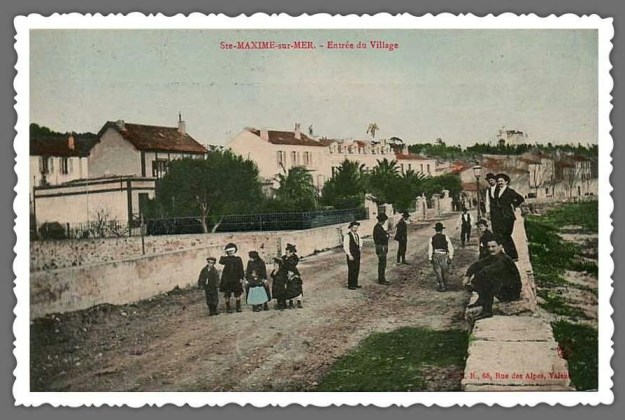

A very early view of Sainte-Maxime showing the main road into the village from the West.

A very early view of Sainte-Maxime showing the main road into the village from the West.

The image below shows a temporary railway installed by a contractor in the centre of the village to facilitate the construction work on the harbour walls. The church and the defensive tower are in evidence as well.

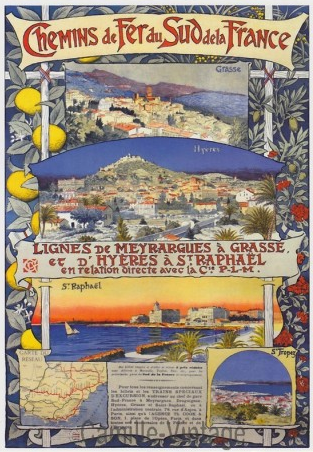

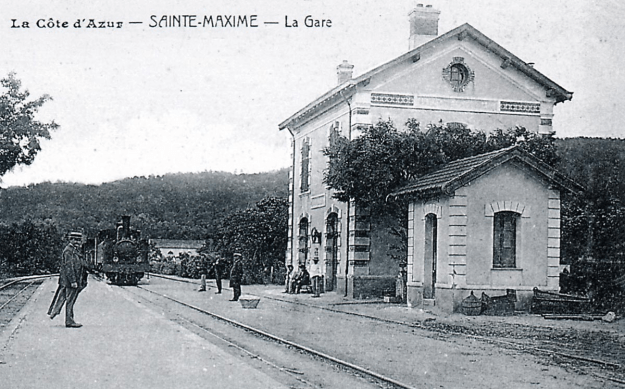

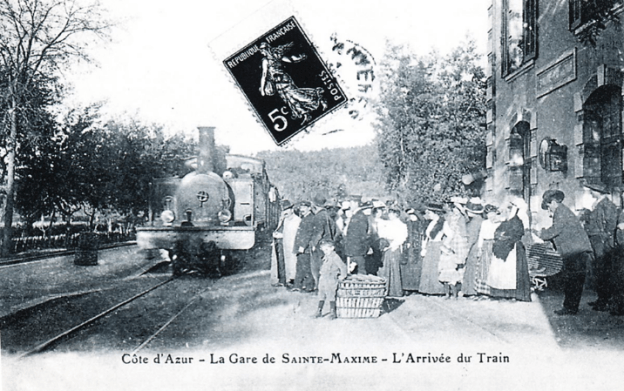

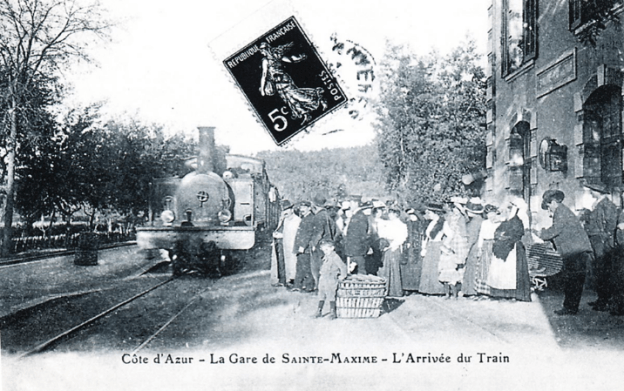

We will focus now on the station. The image below shows a train arriving from St. Raphael. The picture shows the Station building after it had had been enlarged by two single story wings.

We will focus now on the station. The image below shows a train arriving from St. Raphael. The picture shows the Station building after it had had been enlarged by two single story wings.

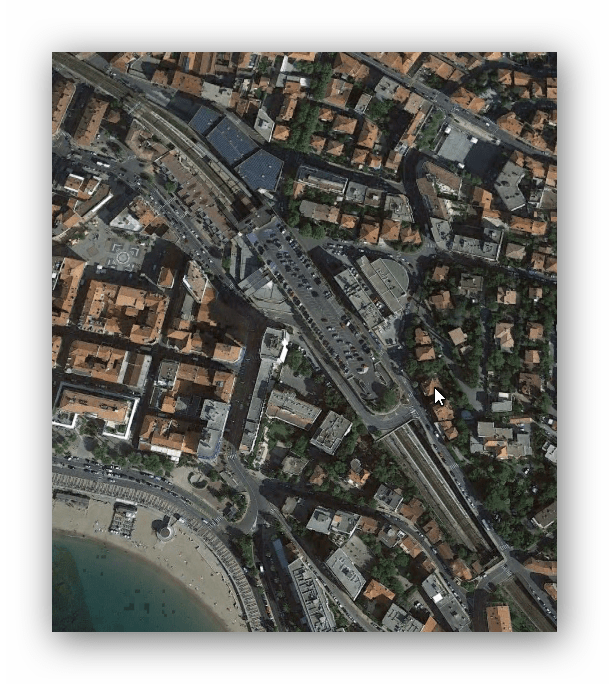

This aerial view of Sainte-Maxime was taken after the Second World War. It seems to show a breach in the harbour wall. The defensive tower and the church can be seen in the bottom right of the image close to the landward end of the harbour wall. The railway line is highlighted in orange with the station location flagged. At this time the station location was on the very edge of the village with open fields beyond.

This aerial view of Sainte-Maxime was taken after the Second World War. It seems to show a breach in the harbour wall. The defensive tower and the church can be seen in the bottom right of the image close to the landward end of the harbour wall. The railway line is highlighted in orange with the station location flagged. At this time the station location was on the very edge of the village with open fields beyond.

In this early shot of the station from the South-east, we see the original building without the extensions. Horse-drawn carriages make the connection between the village centre and the station. The picture was taken shortly after 1900 (Paul CARENCO Collection).

In this early shot of the station from the South-east, we see the original building without the extensions. Horse-drawn carriages make the connection between the village centre and the station. The picture was taken shortly after 1900 (Paul CARENCO Collection).

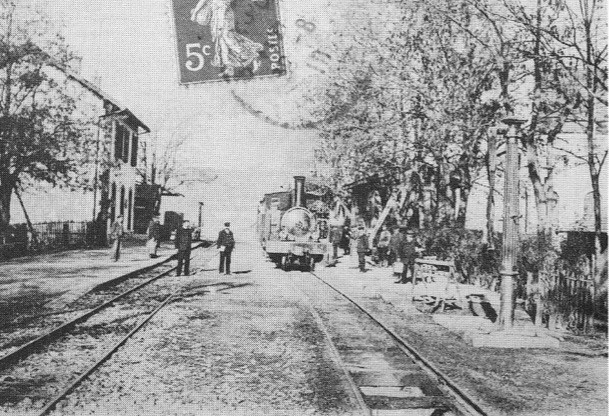

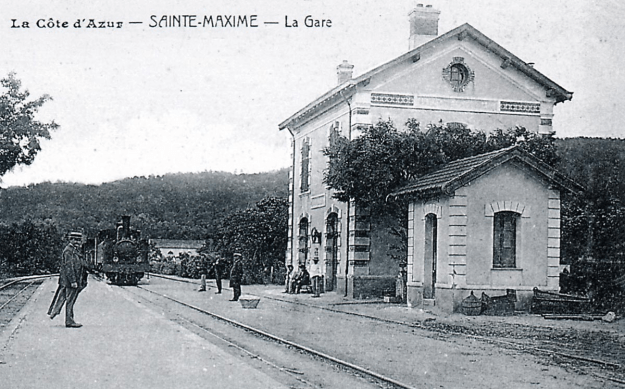

Also taken before the extensions were built and not showing the goods shed, although this may be just off the picture to the right, this image shows another train arriving from St. Raphael on its way to Toulon. The setting of the station is rural. The picture was taken around 1905 (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

Also taken before the extensions were built and not showing the goods shed, although this may be just off the picture to the right, this image shows another train arriving from St. Raphael on its way to Toulon. The setting of the station is rural. The picture was taken around 1905 (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

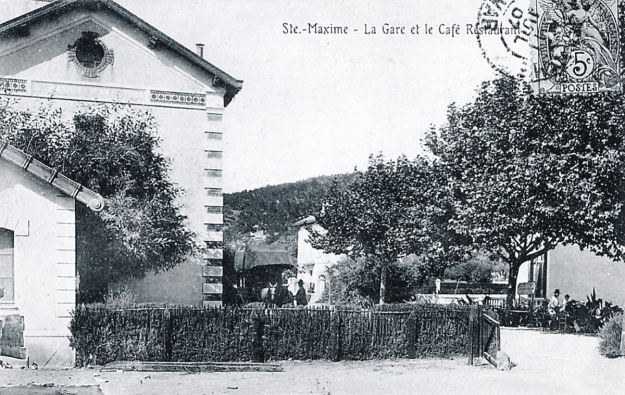

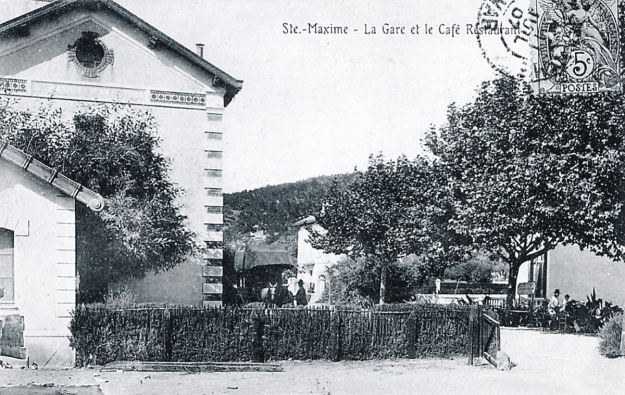

This photograph shows the Station and the Station Café early in the 1900s. The extensions on the station building are not yet built. Horse-drawn carriages are once again in evidence (Paul CARENCO Collection).

This photograph shows the Station and the Station Café early in the 1900s. The extensions on the station building are not yet built. Horse-drawn carriages are once again in evidence (Paul CARENCO Collection).

The village was sometimes known as Sainte-Maxime-Plan-de-la-Tour or Sainte-Maxime-sur-Mer. This image is taken in around 1910 and the station is busy. On the left is a short passenger train from La Foux – St.Raphaël. To its right, we see bags piled up on the platform, a cart loaded with furniture, barrels of wine on an open wagon (Buire X-147) which is equipped with a seat for the brakeman. We also can see, on the left of the picture, workers unloading a De Dietrich t-1571 wagon under the canopy of the goods shed (Pierre VIROT Collection).

The village was sometimes known as Sainte-Maxime-Plan-de-la-Tour or Sainte-Maxime-sur-Mer. This image is taken in around 1910 and the station is busy. On the left is a short passenger train from La Foux – St.Raphaël. To its right, we see bags piled up on the platform, a cart loaded with furniture, barrels of wine on an open wagon (Buire X-147) which is equipped with a seat for the brakeman. We also can see, on the left of the picture, workers unloading a De Dietrich t-1571 wagon under the canopy of the goods shed (Pierre VIROT Collection).

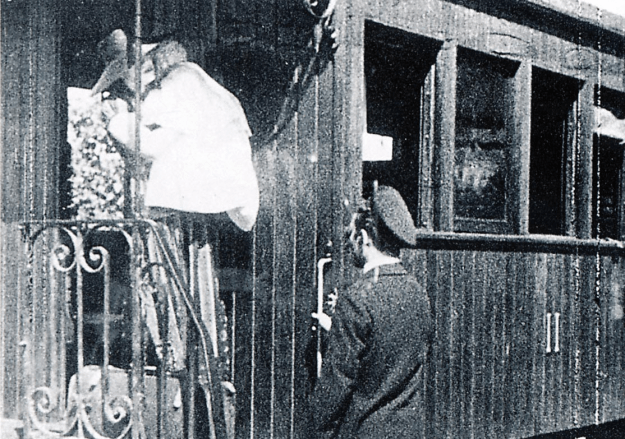

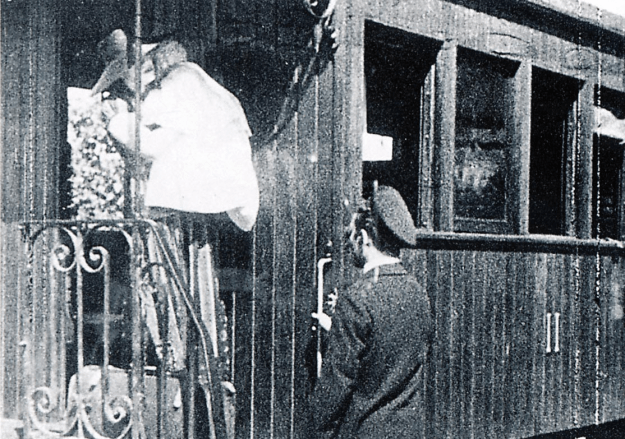

In this photo, the conductor guides passengers into a carriage at Sainte-Maxime. The picture was taken in 1925 (François MORENAS collection).

In this photo, the conductor guides passengers into a carriage at Sainte-Maxime. The picture was taken in 1925 (François MORENAS collection).

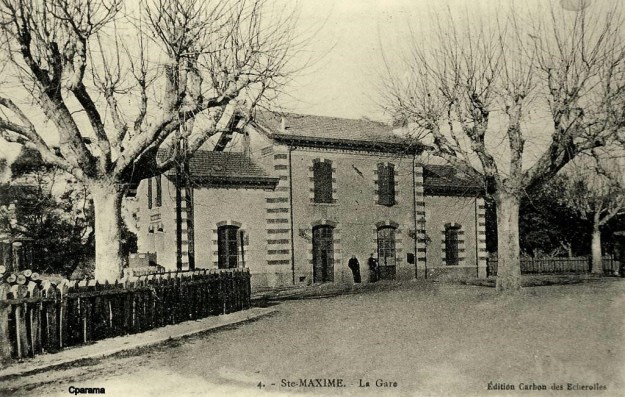

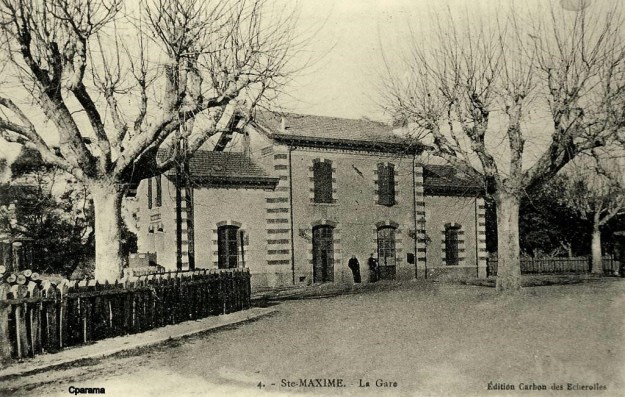

The extended passenger station building taken in winter from the station square.

The extended passenger station building taken in winter from the station square.

This picture was taken in 1965 and shows the station site from the North.

This picture was taken in 1965 and shows the station site from the North.

Two interesting cameos now follow.

The first is of the station after the tidal wave of 28th September 1932. It shows a train of good wagons half overturned by the waves (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

The first is of the station after the tidal wave of 28th September 1932. It shows a train of good wagons half overturned by the waves (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

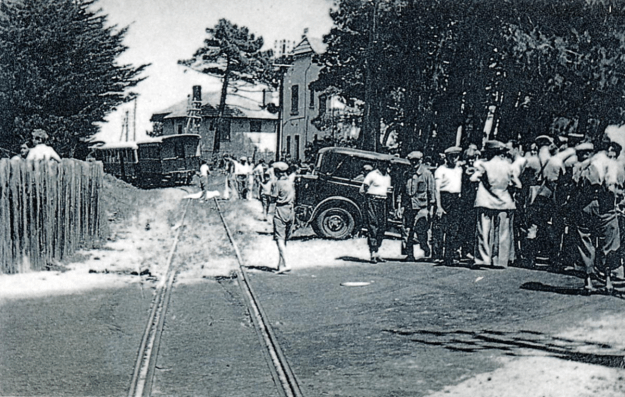

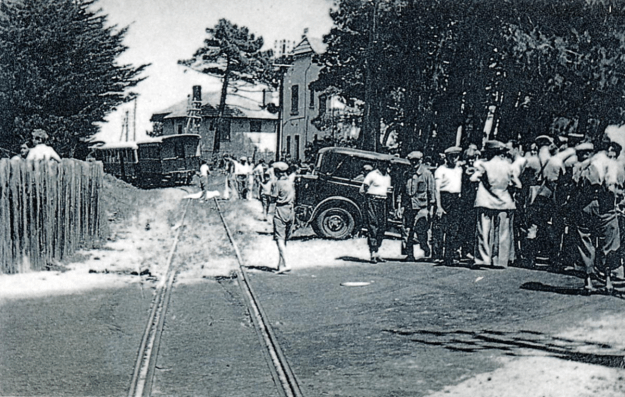

The second is taken immediately after an accident at the railway crossing over Le Petite Pointe on 13th June 1937. A Brissonneau & Lotz railcar towing a bogie car hit a motor car crossing the track at the entrance to the station (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

The second is taken immediately after an accident at the railway crossing over Le Petite Pointe on 13th June 1937. A Brissonneau & Lotz railcar towing a bogie car hit a motor car crossing the track at the entrance to the station (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

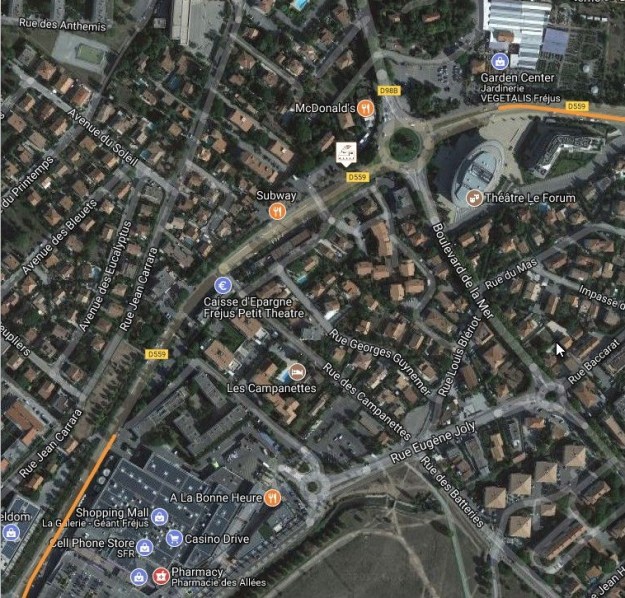

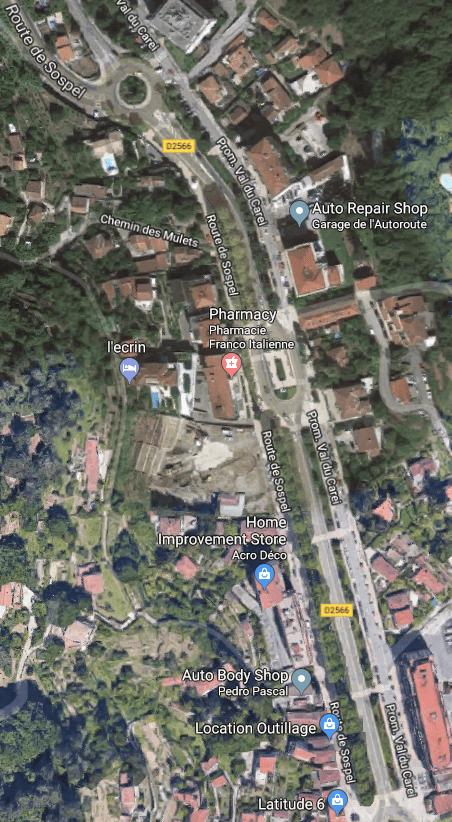

And finally, the Station site in Sainte-Maxime remains as an open space, it is the market place. Moreau [3] has shown the route of the line as an overlay on the satellite images from Google.

And finally, the Station site in Sainte-Maxime remains as an open space, it is the market place. Moreau [3] has shown the route of the line as an overlay on the satellite images from Google.

Back at the station, we wait for the train to St. Raphael.

Back at the station, we wait for the train to St. Raphael.

The train sets off around the back of Sainte-Maxime and out in a big loop into what was countryside, following what is now the Route Jean Corona, now a one-way street heading approximately North-East to South-West, but then a single-track line carrying trains in both directions. After a roundabout the road name changes to Avenue du Debarquement and runs roughly West to East. The formation is overlain by tarmac but can be seen on the left in the first colour image.

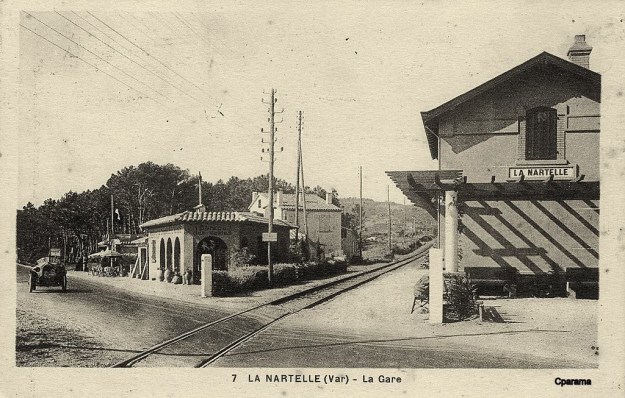

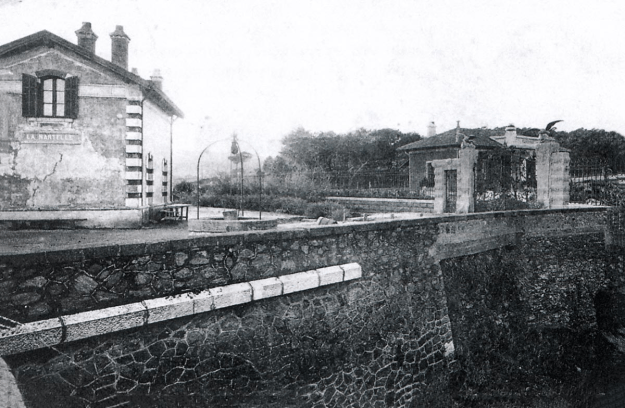

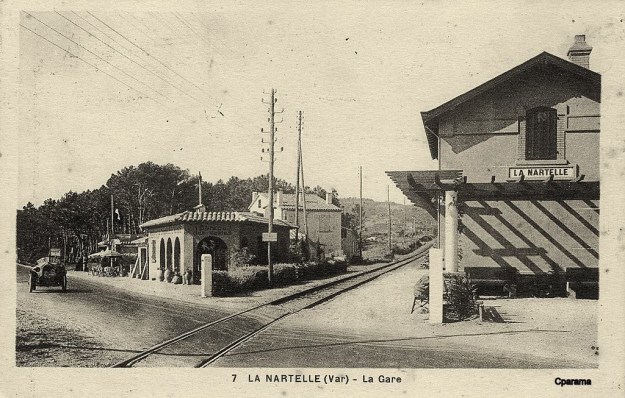

As the road and the line get closer once again to the coast, the line swings away north of the Avenue du Debarquement and eventually finds itself following what is now called Place du 2eme Regiment de Cuirassier into Nartelle. The next image is taken looking back down the line towards Sainte-Maxime. Despite redevelopment of the area, the layout of the buildings in this immediate location remains roughly the same as it was when the line was in use. The monochrome photograph was taken in the 1930s and shows the station building for the halt of La Nartelle (Collection Pierre LECROULANT). The station building is now a private dwelling.

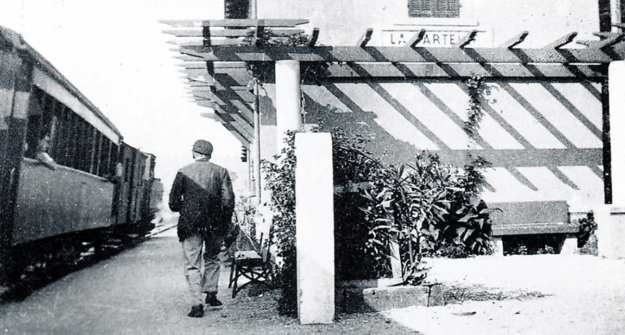

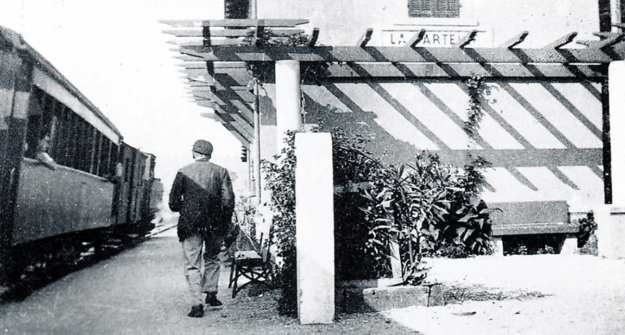

Despite a general deterioration in the maintenance of fixed installations along the line, some of the halts frequented by tourists were improved in the years 1925-30: this is the case here at the La Nartelle halt, which received new benches and a pergola (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – Pierre VIROT collection).

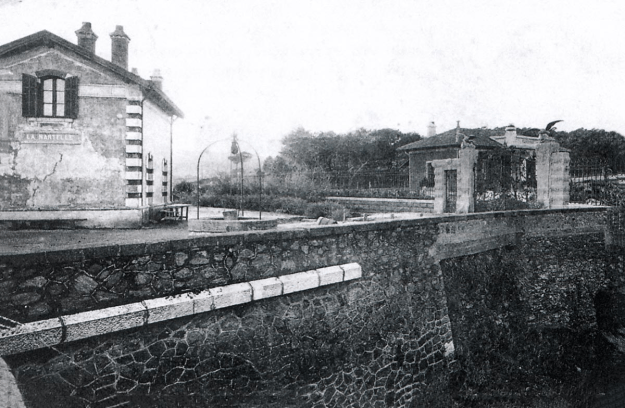

The halt was very close to the sea wall, as this image makes clear. The gates to the right of the picture have long-gone but gave access onto an estate which was owned by a German family – the Kronprinz estate. The railway continued off to the right of the picture above the sea wall.

The halt was very close to the sea wall, as this image makes clear. The gates to the right of the picture have long-gone but gave access onto an estate which was owned by a German family – the Kronprinz estate. The railway continued off to the right of the picture above the sea wall.

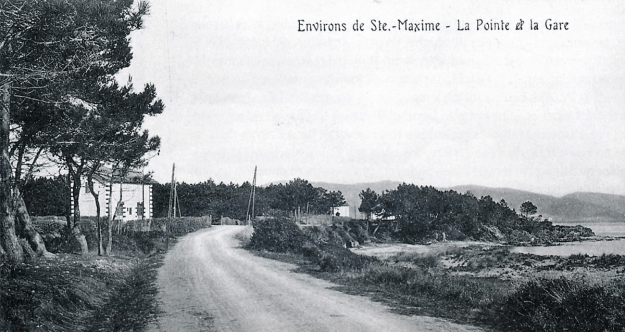

I remain to be convinced, but Jean-Pierre Moreau says that the photo above is taken at the same location where the coast-road and the railway meet at La Nartelle after the railway has looped round the back of Sainte-Maxime. If this is the case, then this is a much earlier image and is taken before there has been any significant development at La Nartelle (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

I remain to be convinced, but Jean-Pierre Moreau says that the photo above is taken at the same location where the coast-road and the railway meet at La Nartelle after the railway has looped round the back of Sainte-Maxime. If this is the case, then this is a much earlier image and is taken before there has been any significant development at La Nartelle (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

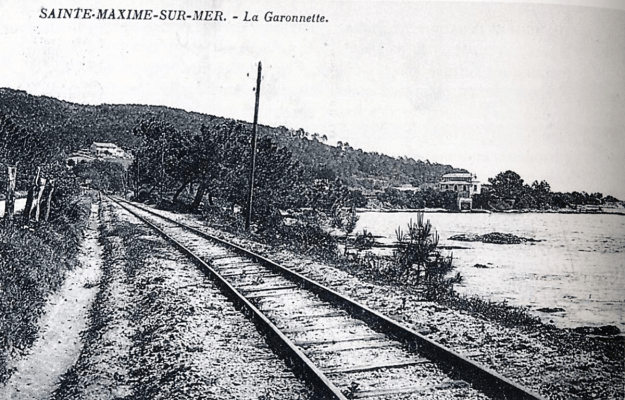

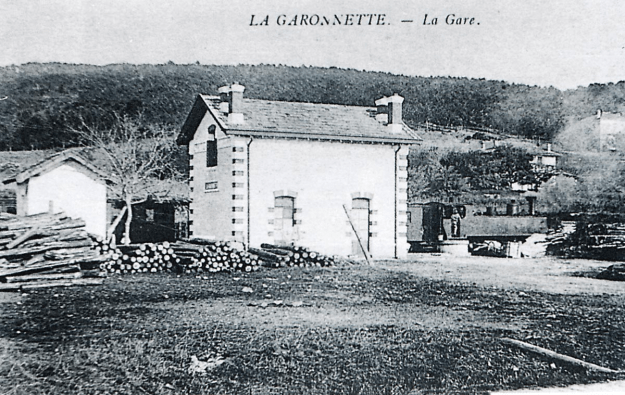

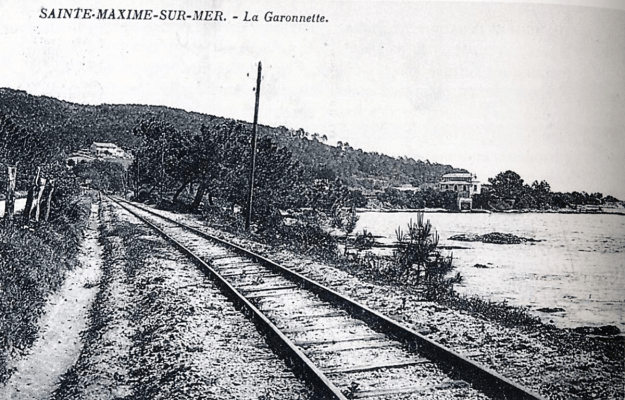

The railway continues from La Nartelle along the sea wall and beside the road (now the D559) through Le Saut-du-Loup, a halt that was opened in 1938 and on towards La Garonnette-Plage Val-d’Esquières (originally La Garonnette-Plage) which was opened in 1913.

This picture shows the railway between the two halts close to La Garonnette-Plage. The formation has been ballasted with earth and gravel from La Garonette beach (Pierre LECROULANT Collection).

This picture shows the railway between the two halts close to La Garonnette-Plage. The formation has been ballasted with earth and gravel from La Garonette beach (Pierre LECROULANT Collection).

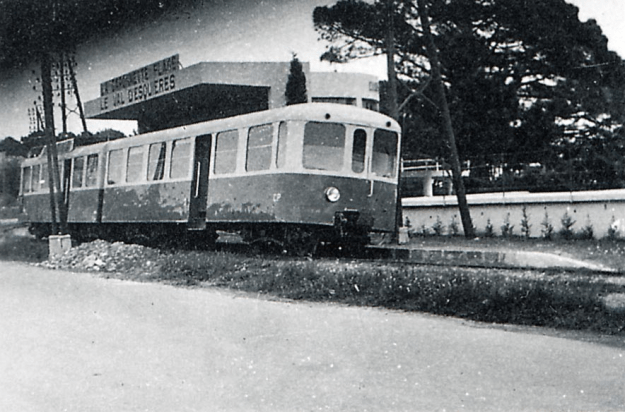

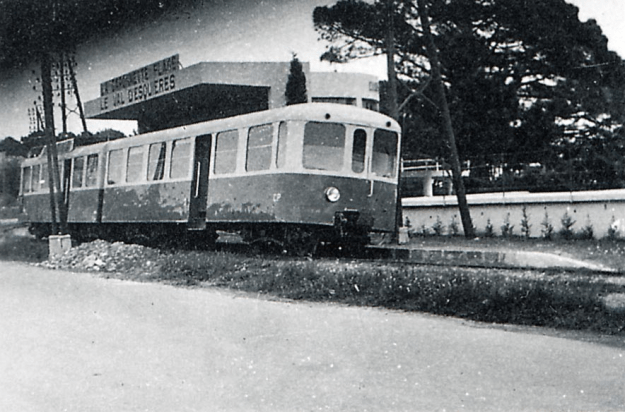

The Brissonneau & Lotz railcar is stopped at La Garonnette-Plage Val-d’Esquières. It has a concrete shelter. The picture was taken in around 1938 (Collection Pierre LECROULANT).

The Brissonneau & Lotz railcar is stopped at La Garonnette-Plage Val-d’Esquières. It has a concrete shelter. The picture was taken in around 1938 (Collection Pierre LECROULANT).

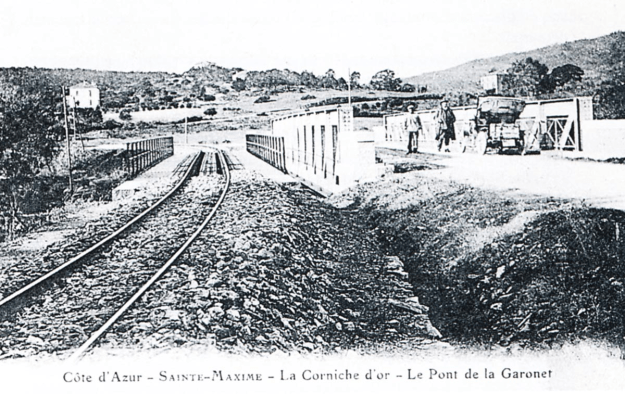

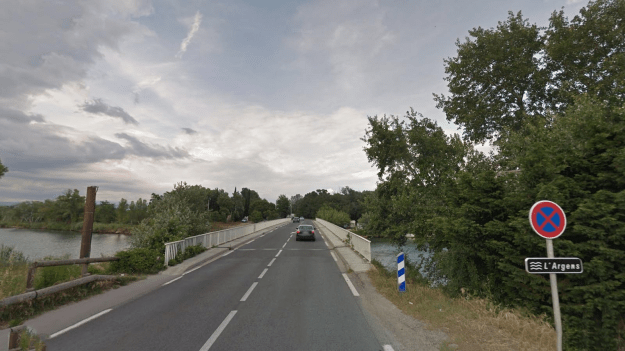

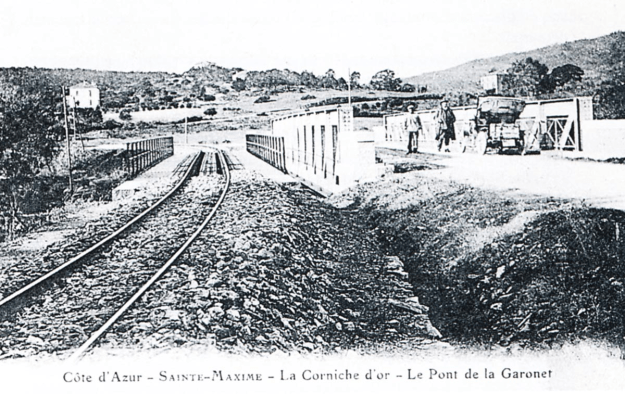

Immediately after the stop of La Garonette-Plage-Val d’Esquières, the line crossed the Pont de la Garonette. The picture below is taken looking back toward Sainte-Maxime. The bridge was a metal structure which was given a new 23 metre deck after the original had been washed away in 1901 (Pierre VIROT collection).

The structure is shown below in a 1978 photograph when the parallel road structure was still a single-lane metal bridge as well.

The structure is shown below in a 1978 photograph when the parallel road structure was still a single-lane metal bridge as well.

Around 1985, the latter was rebuilt in concrete and, during construction a crane on a temporary track of metre gauge was installed on the old railway bridge to facilitate the handling of materials (Photo José BANAUDO).

Around 1985, the latter was rebuilt in concrete and, during construction a crane on a temporary track of metre gauge was installed on the old railway bridge to facilitate the handling of materials (Photo José BANAUDO).

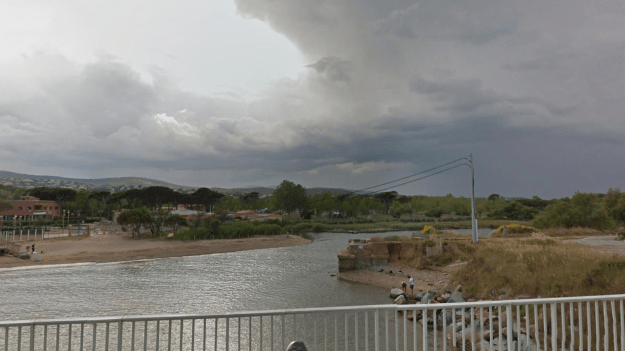

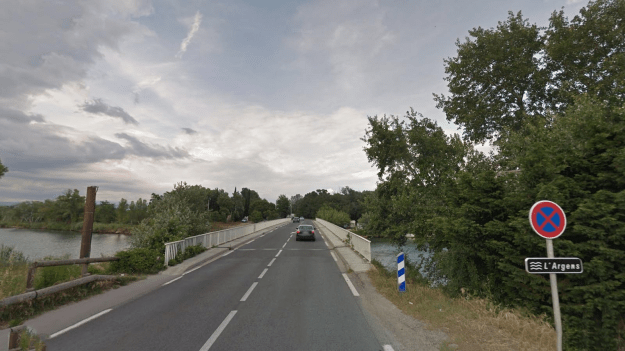

In the early 21st Century, the old railway bridge still sits alongside the much newer road bridge.

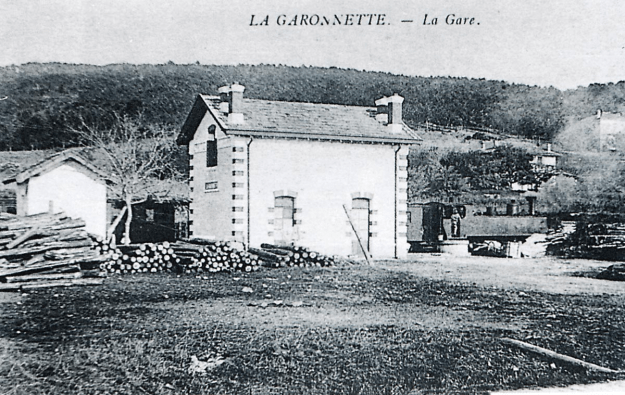

Beyond the bridge the railway continues to run between road and sea-shore, until perhaps 300 metres, before reaching the halt of La Garonnette San-Peire (originally La Garonnette). Here the railway slipped away inland a little from the road. The formation can be seen under tarmac on the left of the picture below.

Within 300 metres of this point the line ran into the halt of La Garonnette San-Piere. It was an important goods loading point. Wood from Les Maures forests was a major source of traffic, and in the image below we can see a lot of pit props ready to be loaded onto a goods train at La Garonnette station. The locomotive in this view is a 4-6-0T SACM locomotive series 61 – 62 (Jean BAZOT Collection).

From this point the railway followed the curvature of the hill rising slightly above the road and running a little inland from the D559, first along what is now Allee de l’Ombrine, then along what is now called Allee Ancien Train des Pignes. The first Google Streetview image looks back along the line towards La Garonnette Halt. The next halt was Les Issambres, which opened in 1937. The line had now risen to about 18 metres above sea-level. The second Google Streetview image looks forward along the line from close to Les Issambres.

From this point the railway followed the curvature of the hill rising slightly above the road and running a little inland from the D559, first along what is now Allee de l’Ombrine, then along what is now called Allee Ancien Train des Pignes. The first Google Streetview image looks back along the line towards La Garonnette Halt. The next halt was Les Issambres, which opened in 1937. The line had now risen to about 18 metres above sea-level. The second Google Streetview image looks forward along the line from close to Les Issambres.

The line is in cutting and by this time it is travelling Northwards. It crosses a stream valley, although it is impossible to see the culvert which must carry water under the route of the line. Within about 500 meters the line is back close to the D559.

The line is in cutting and by this time it is travelling Northwards. It crosses a stream valley, although it is impossible to see the culvert which must carry water under the route of the line. Within about 500 meters the line is back close to the D559.

The vehicles parked on the left-hand verge of the D559 in the next picture are on the formation of the old railway.

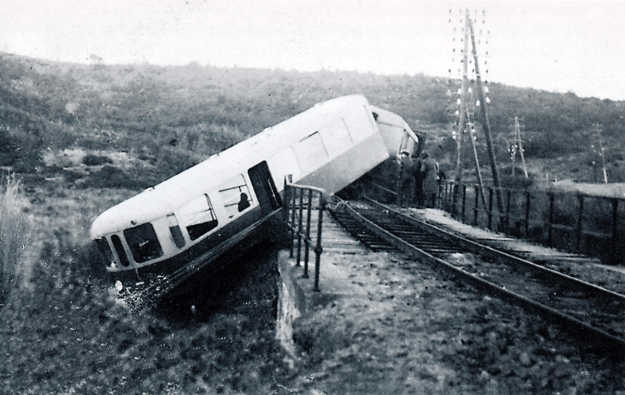

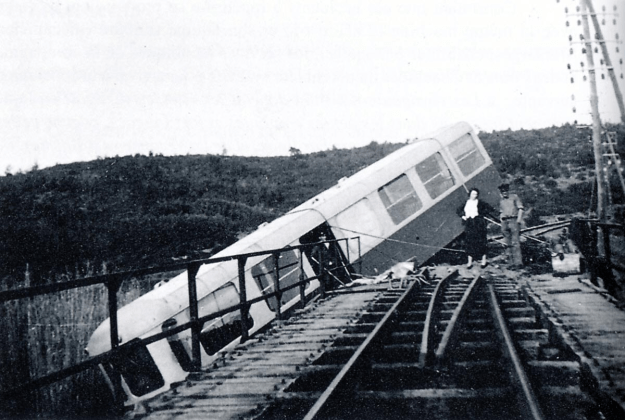

The line continues beside the road through the halt called La Gaillarde and across the Pont de la Gaillarde, a 10 metre span metal girder bridge.

The line continues beside the road through the halt called La Gaillarde and across the Pont de la Gaillarde, a 10 metre span metal girder bridge.

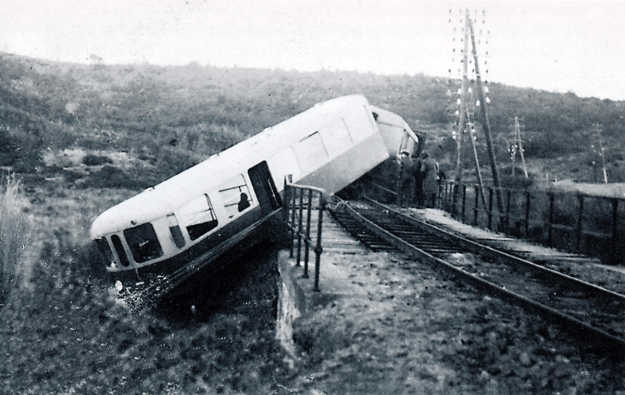

This was the site of an accident on 22nd January 1938. The Railcar which was providing service 108 between St. Raphael and Toulon derailed as a result of a broken axle in its trailer (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

This was the site of an accident on 22nd January 1938. The Railcar which was providing service 108 between St. Raphael and Toulon derailed as a result of a broken axle in its trailer (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

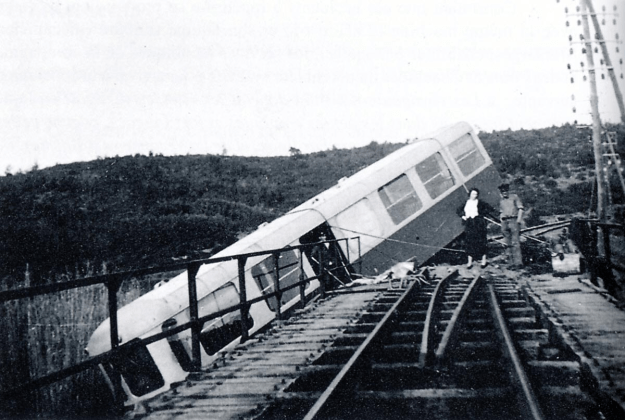

The second image of this accident is taken after the trailer car has been removed and the immediately damaged track lifted (GECP Collection).There is a cycleway on the line of the railway now and that cycleway has been provided with a new bridge in the same location as the old railway bridge.

The second image of this accident is taken after the trailer car has been removed and the immediately damaged track lifted (GECP Collection).There is a cycleway on the line of the railway now and that cycleway has been provided with a new bridge in the same location as the old railway bridge.

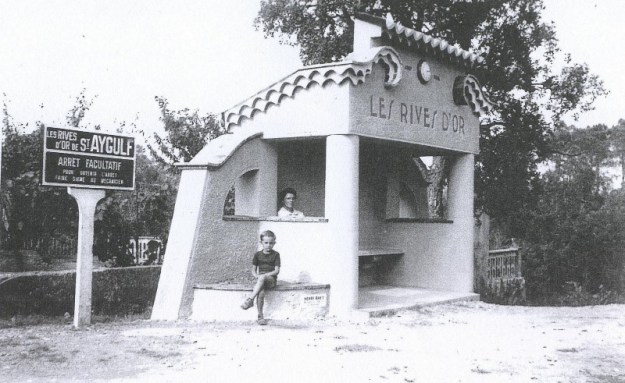

The railway line continues alongside the D559 and its formation continues to be under a cycleway. For some distance this runs above the height of the road by a metre or two. The line then, once again, leaves the D559, this time along what is now Boulevard Alexis Carrel. It does not return to run alongside the D559 until another kilometre has passed. The Boulevard Alexis Carrel is another single-lane road and is restricted to one-way traffic, this time in a North-Easterly direction.

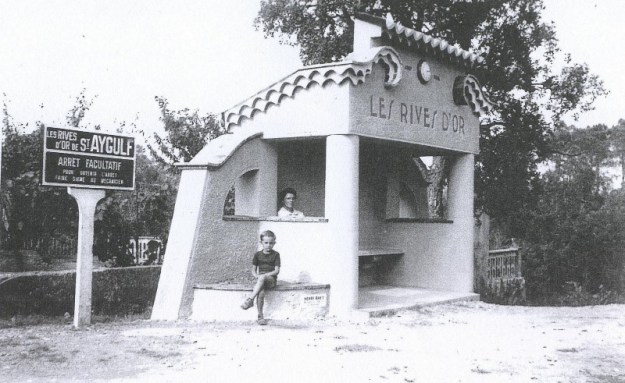

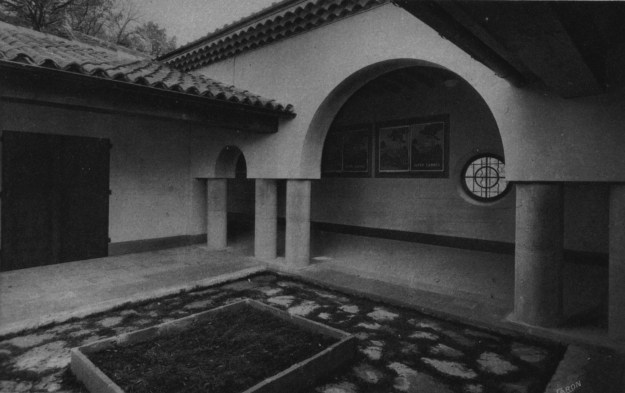

Just before returning to run alongside the D559 the line passed through the halt of Les Rives-d’Or. This halt had a concrete shelter and opened in 1938. The photo was probably taken that year (Robert ALEXANDRE Collection).

Just before returning to run alongside the D559 the line passed through the halt of Les Rives-d’Or. This halt had a concrete shelter and opened in 1938. The photo was probably taken that year (Robert ALEXANDRE Collection).

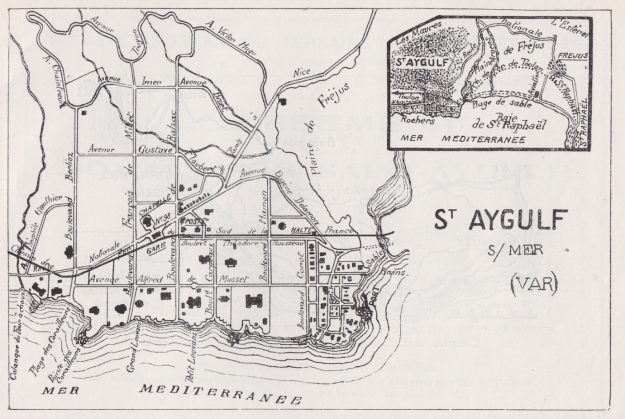

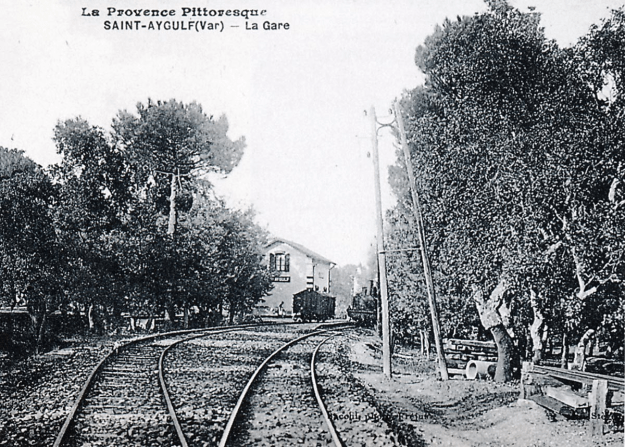

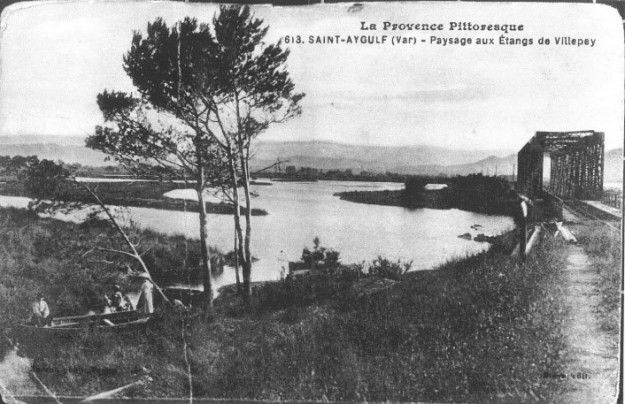

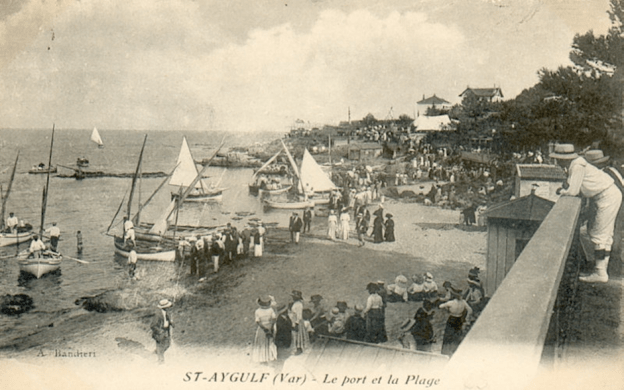

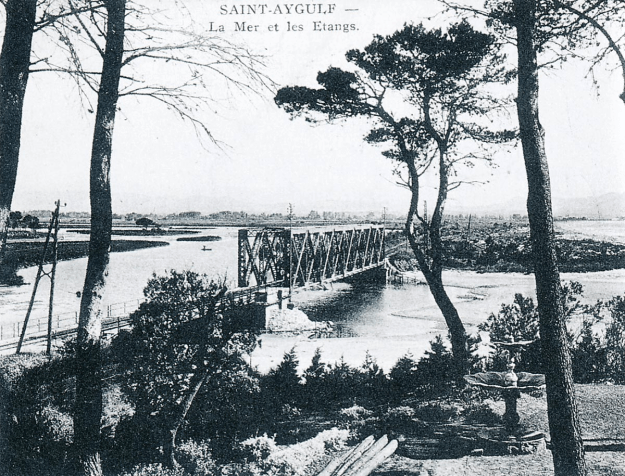

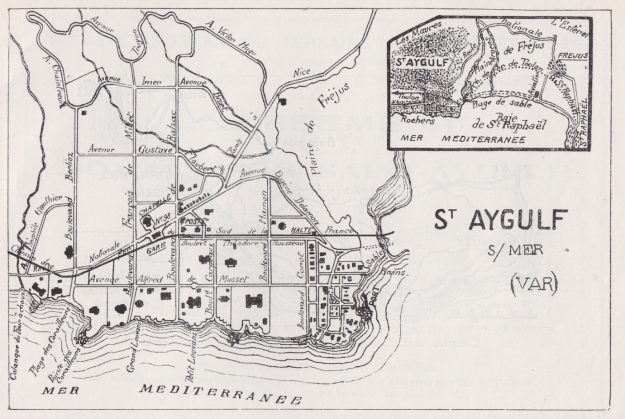

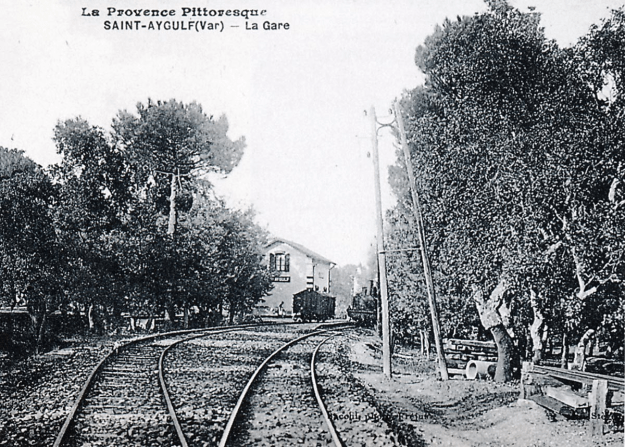

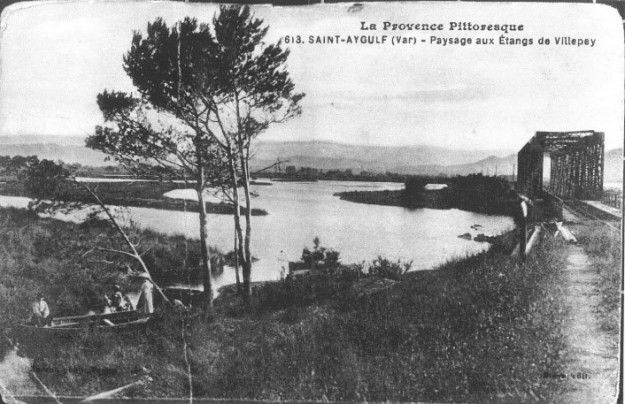

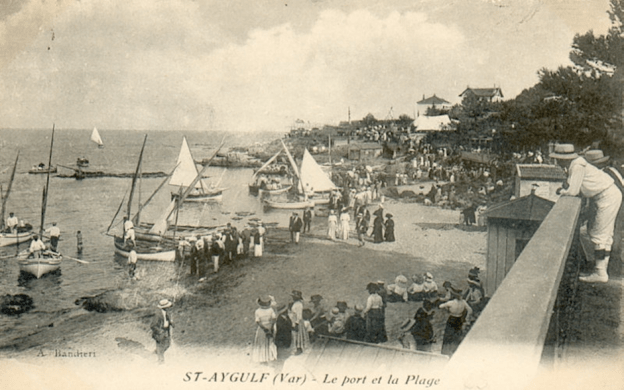

We are now approaching the next significant stop on the line – St. Aygulf. Although this was only classed as a halt it grew to have a reasonable importance in the years prior to the Second World War. The St. Aygulf station was sheltered amidst the cork oaks as can be seen on the photograph below the plan (incidentally the plan is oriented along the line which was actually travelling roughly North-South, not East-West). The town was known as “Rocquebrunre/Saint-Aygulf” until 1894.

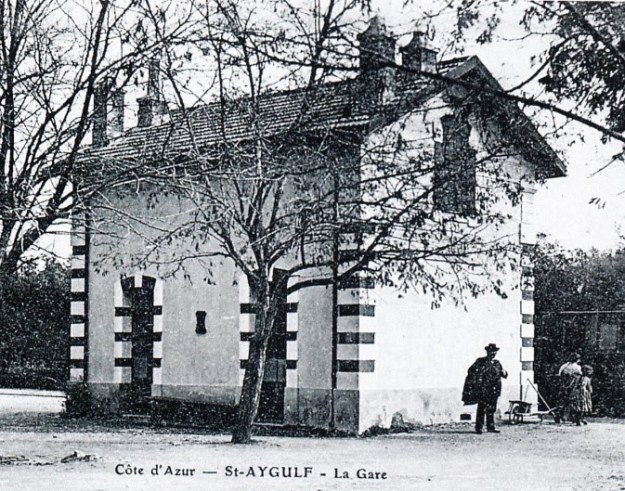

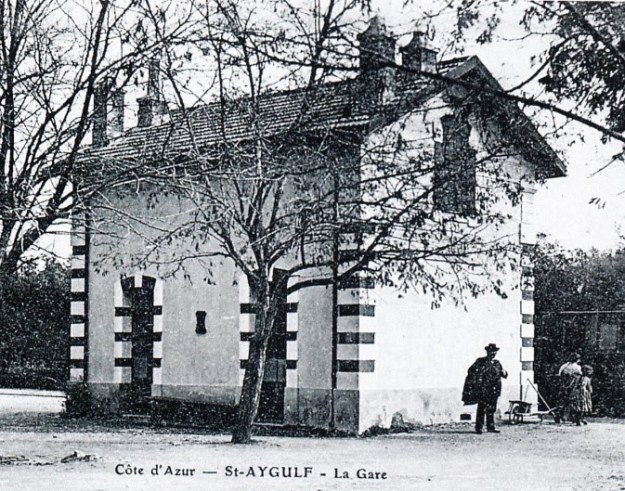

The station opened with the line in 1889 with a single line and a small station building. This was augmented in 1890 by a single siding facing St. Raphaël and a goods platform. The siding was then turned into a loop in 1894. The station was demolished in 1944 by German troops organising defences against possible invasion (Pierre NICOLINI Collection).

The station opened with the line in 1889 with a single line and a small station building. This was augmented in 1890 by a single siding facing St. Raphaël and a goods platform. The siding was then turned into a loop in 1894. The station was demolished in 1944 by German troops organising defences against possible invasion (Pierre NICOLINI Collection).

As soon as the Littoral line was opened, additional work was carried out in some stations to adapt them for the traffic which they were experiencing. This picture from the last years of the 19th Century shows the two tracks through the station. The main track is laid on crushed stone ballast, while the goods track created in 1890 is based on a sand ballast (Pierre NICOLINI Collection).

As soon as the Littoral line was opened, additional work was carried out in some stations to adapt them for the traffic which they were experiencing. This picture from the last years of the 19th Century shows the two tracks through the station. The main track is laid on crushed stone ballast, while the goods track created in 1890 is based on a sand ballast (Pierre NICOLINI Collection).

In these next pictures the station is seen first from the courtyard (Raymond BERNARDI Collection) and then from the platform side.

Significant activity is taking place in the second image. A mixed train from St. Raphael to Toulon has stopped at the station in around 1925. On the siding a shallow open wagon and a box wagon can be seen alongside the mixed train (Pierre NICOLINI Collection).

Significant activity is taking place in the second image. A mixed train from St. Raphael to Toulon has stopped at the station in around 1925. On the siding a shallow open wagon and a box wagon can be seen alongside the mixed train (Pierre NICOLINI Collection).

Train 103 from Toulon to St. Raphael was involved in an accident on 11th January 1924 at St. Aygulf (Paul CARENCO Collection).

Train 103 from Toulon to St. Raphael was involved in an accident on 11th January 1924 at St. Aygulf (Paul CARENCO Collection).

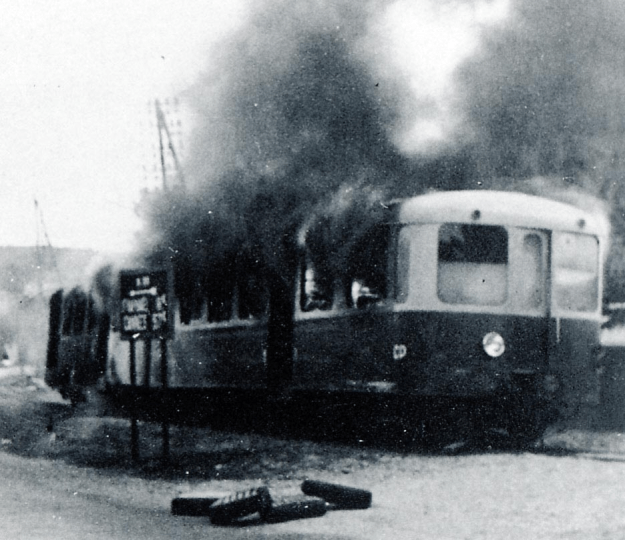

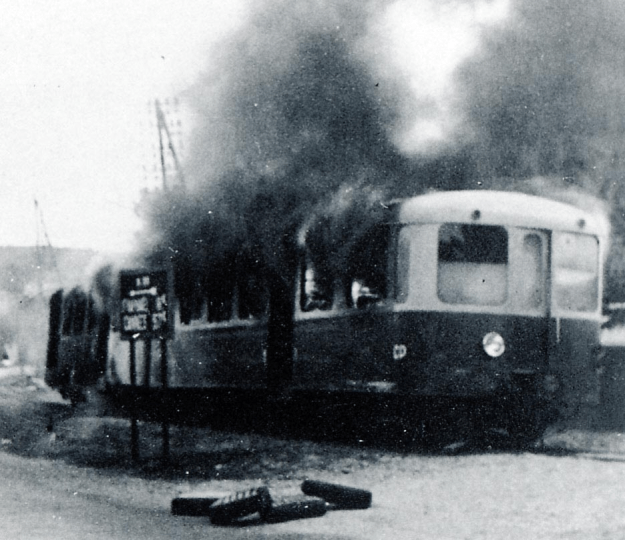

A Brissonneau & Lotz railcar burned in full close to St.Aygulf: this is probably one of two trains accidentally destroyed in this way in autumn 1937, which necessitated replacement by two new units the next year (Paul CARENCO Collection). The fire started in the motor unit and spread to the trailer, as can be seen below (Paul CARENCO Collection).

A Brissonneau & Lotz railcar burned in full close to St.Aygulf: this is probably one of two trains accidentally destroyed in this way in autumn 1937, which necessitated replacement by two new units the next year (Paul CARENCO Collection). The fire started in the motor unit and spread to the trailer, as can be seen below (Paul CARENCO Collection).

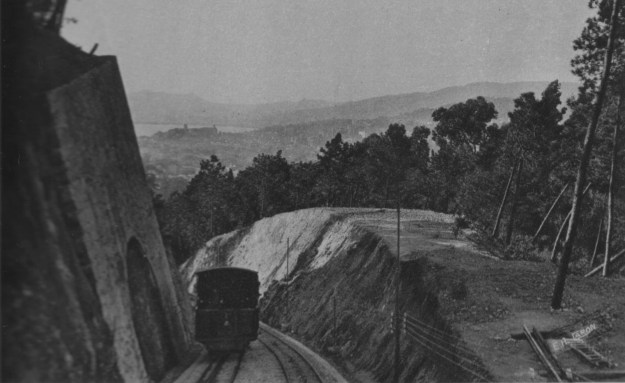

After leaving the Station at St. Aygulf the line entered a deep cutting before reaching the next halt, Saint-Aygulf Plage.

After leaving the Station at St. Aygulf the line entered a deep cutting before reaching the next halt, Saint-Aygulf Plage.

The stop of St. Aygulf Plage was called “Villepey-les-Bains” until 1924. It opened in 1903 but was only open from April to October each year (both pictures from the Pierre NICOLINI Collection).

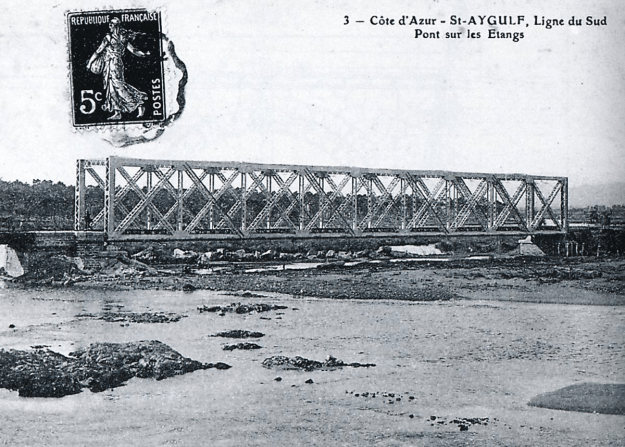

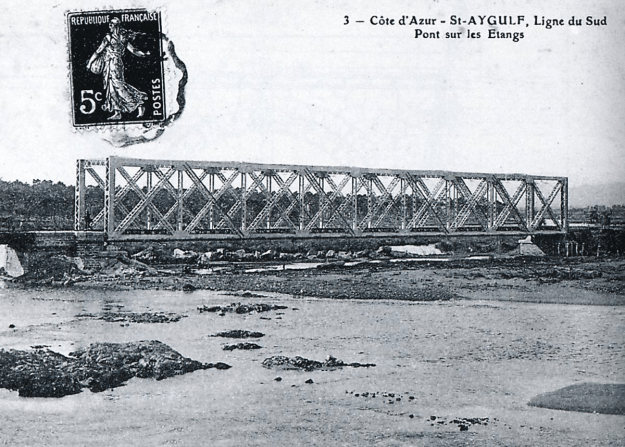

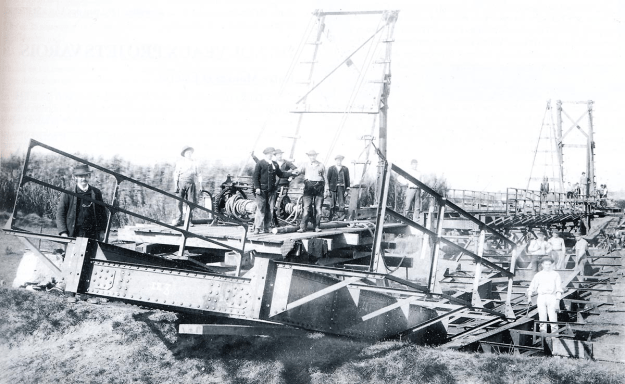

There are two bridges at the main outfall from the Villepey ponds. The first bridges at the site were built by the Eiffel Company. Sadly, these bridges lasted only a short while. There was a flood on 28th November 1900. The 55 metre bridge was washed away and back-filled by 1903. A replacement bridge was built by 1906 by Gosset of Toulon.

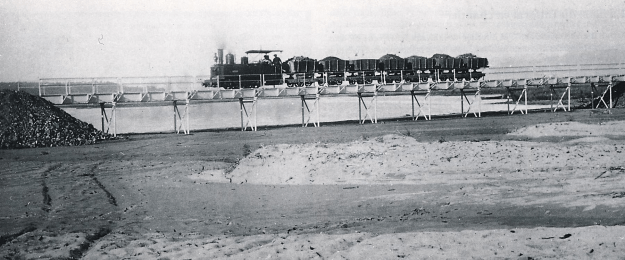

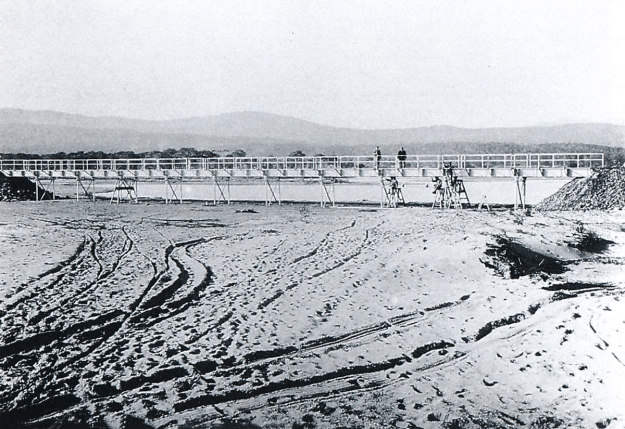

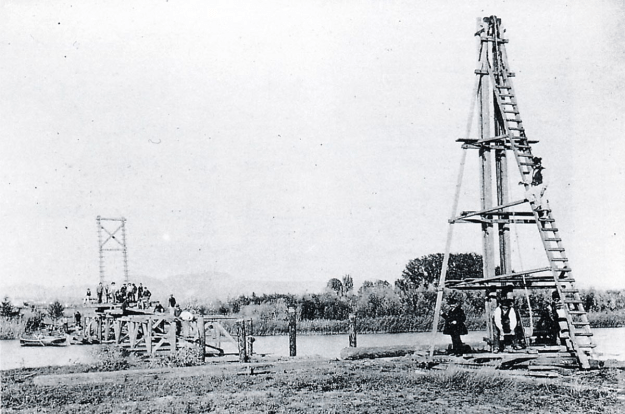

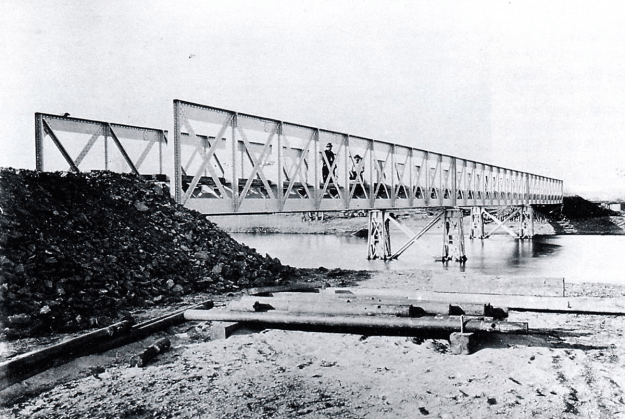

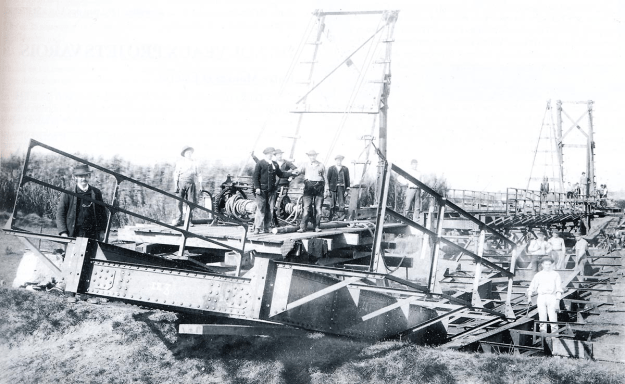

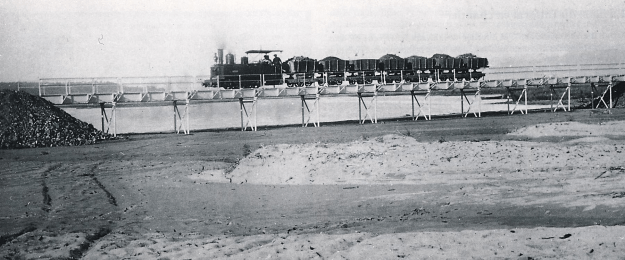

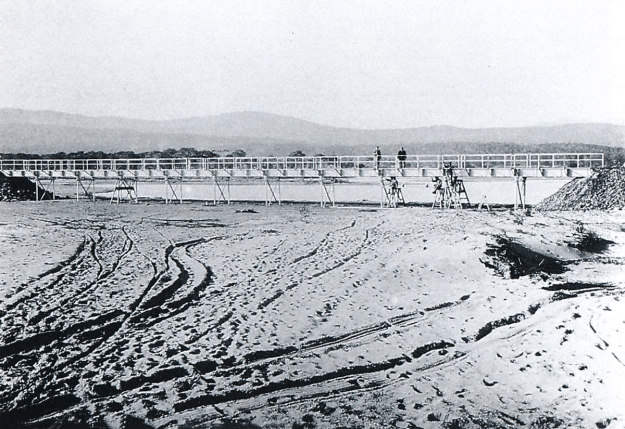

Eiffel built the 55 metre bridge as eleven 5 metre spans. As the pictures show this appeared to be a very fragile structure which might have been adequate for the vertical loading from the trains of the time but probably did not make enough allowance for the dynamic sideways forces it would experience at time of high-flood in the river estuary it crossed, nor even possibly for braking forces from a heavily loaded train. One of the pictures below shows a constructor’s train on the bridge and it seems to dwarf the construction. It is difficult to imagine what this bridge looked like in regular use. The two pictures are from the GECP Collection.

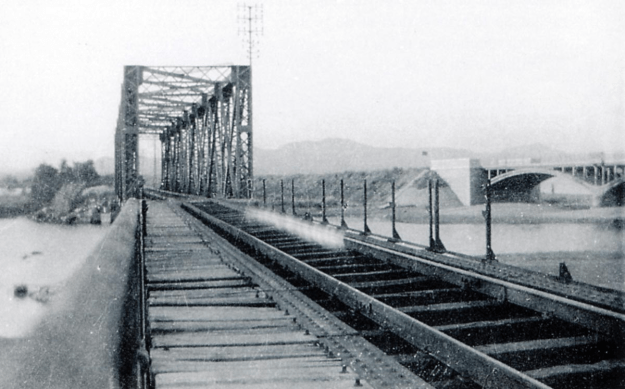

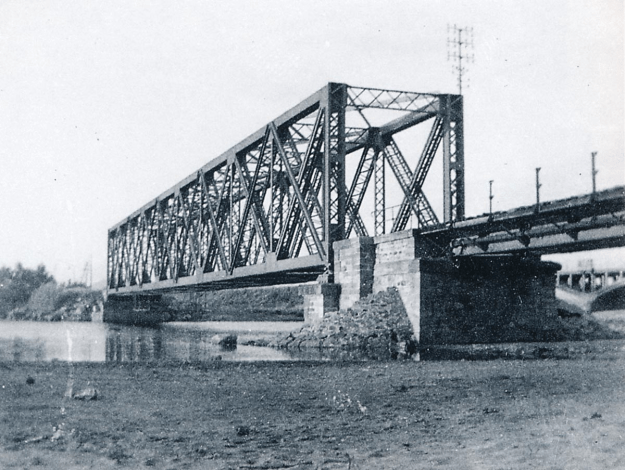

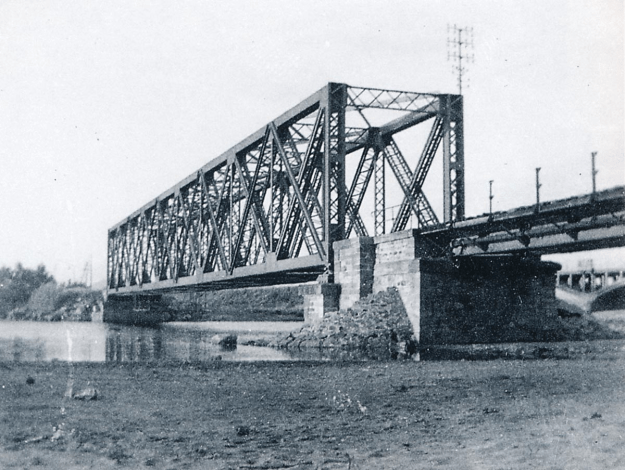

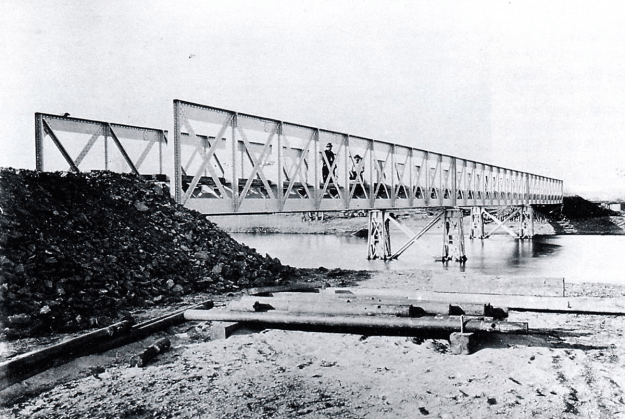

The new bridge was completed in 1906 and proved to be an altogether much more substantial structure. It spanned 57 meters approximately and stood on abutments which have survived into the 21st Century alongside the new road bridge.

The new bridge was completed in 1906 and proved to be an altogether much more substantial structure. It spanned 57 meters approximately and stood on abutments which have survived into the 21st Century alongside the new road bridge.

A number of images of the main span and side spans follow:

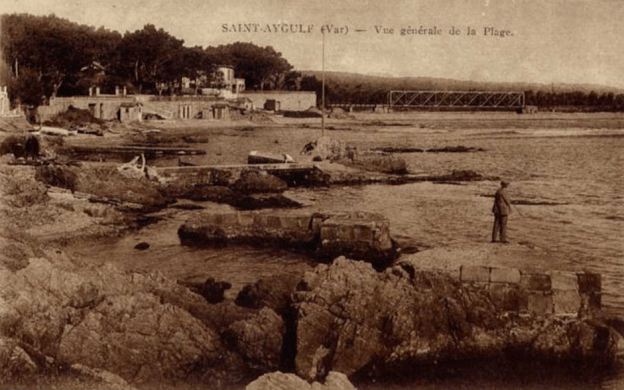

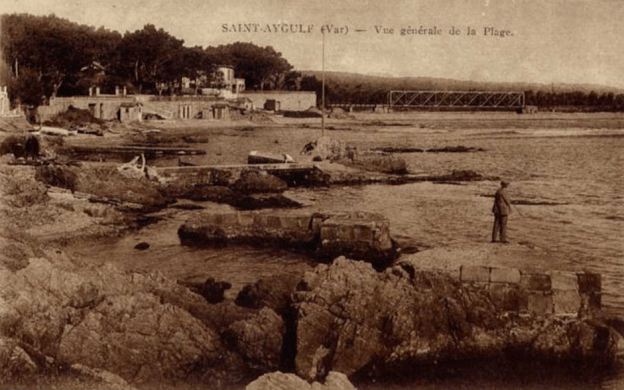

A view of the beach from the railway bridge.

A view of the beach from the railway bridge.

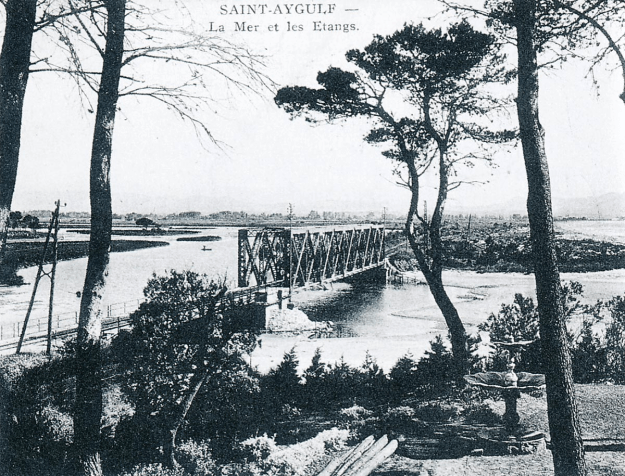

A distant view of the two bridges – Villepey No.1 and Villepey No. 2.

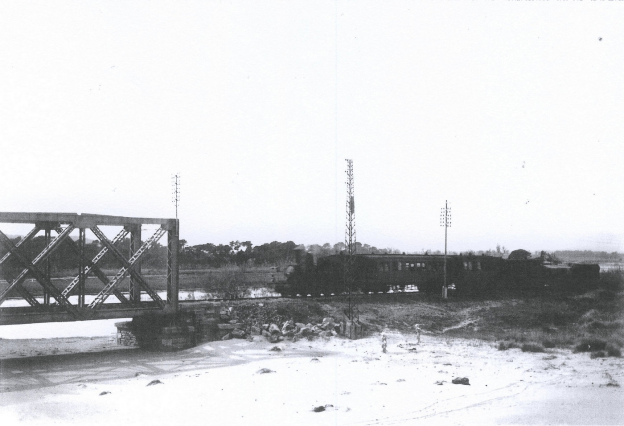

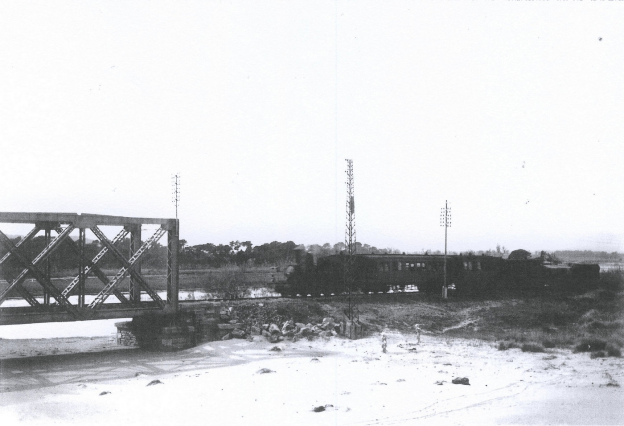

A distant view of the two bridges – Villepey No.1 and Villepey No. 2. In 1925, a train from St. Raphael arrives at the bridge.

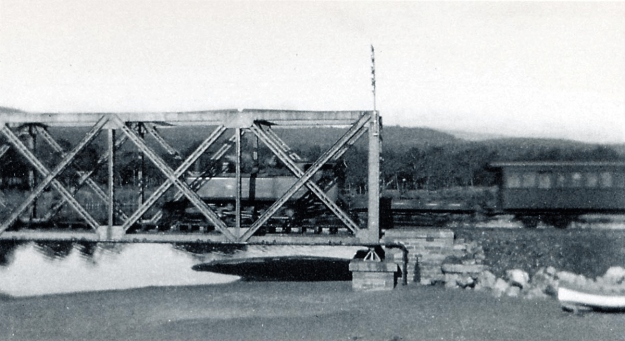

In 1925, a train from St. Raphael arrives at the bridge.

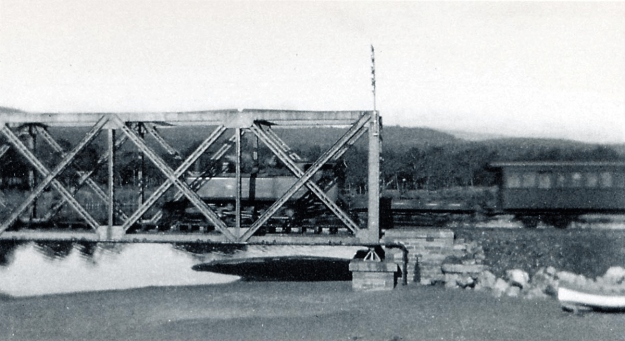

In around 1932, a mixed train from St. Raphael to Toulon crosses the bridge. The bearings and the abutment can easily be seen.

In around 1932, a mixed train from St. Raphael to Toulon crosses the bridge. The bearings and the abutment can easily be seen.

The 57.30 m single-span steel truss bridge of 1906 can be seen at the centre of this picture. In the foreground the short spans approaching the bridge can be seen. These short spans were known as Villepey Bridge No. 1 and the larger span was know as Villepey Bridge No. 2. (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

The 57.30 m single-span steel truss bridge of 1906 can be seen at the centre of this picture. In the foreground the short spans approaching the bridge can be seen. These short spans were known as Villepey Bridge No. 1 and the larger span was know as Villepey Bridge No. 2. (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

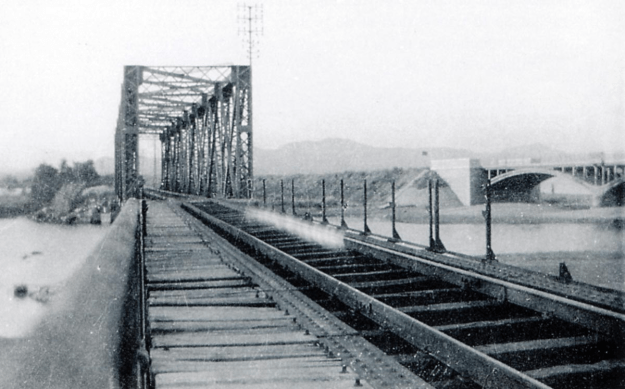

This picture was taken in the years between the two World Wars. The concrete arched road bridge has been completed. It was built in 1931. The photographer is standing on Bridge No. 1 (Photo Charles DAVID).

This picture was taken in the years between the two World Wars. The concrete arched road bridge has been completed. It was built in 1931. The photographer is standing on Bridge No. 1 (Photo Charles DAVID).

The abutment between Bridge No. 1 and Bridge No. 2. The photo is probably taken in 1932 (Photo Charles DAVID).

The abutment between Bridge No. 1 and Bridge No. 2. The photo is probably taken in 1932 (Photo Charles DAVID).

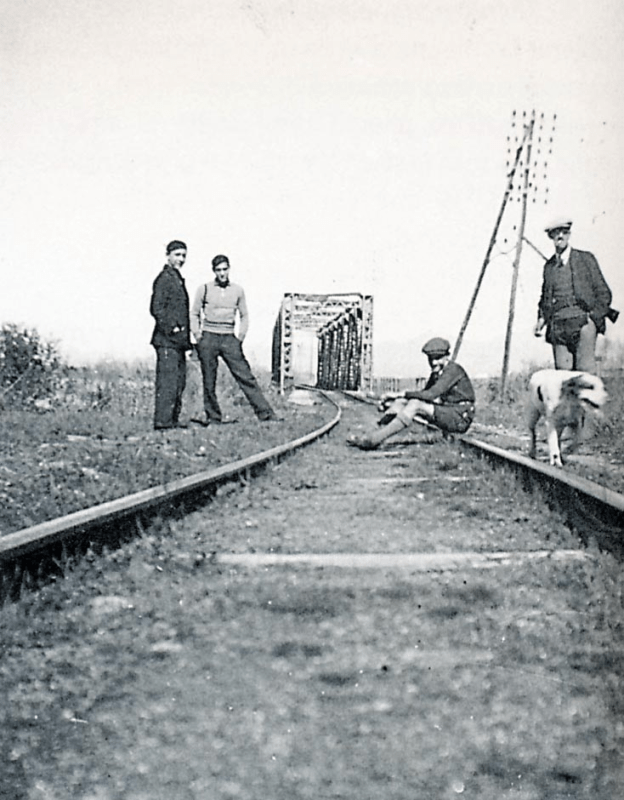

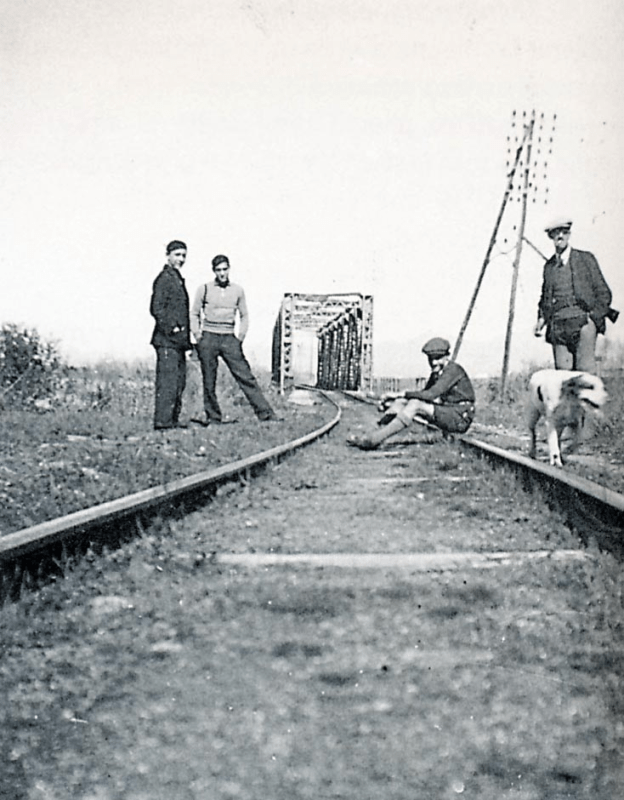

Taken at about the same time. A group of hunters stand on the railway formation (Photo Charles DAVID).

Taken at about the same time. A group of hunters stand on the railway formation (Photo Charles DAVID).

The beach of St. Aygulf attracted crowds of bathers every summer to the Villepey-les-Bains temporary halt. Villepey Bridge No. 2 can be seen in the background (Pierre NICOLINI Collection).

The beach of St. Aygulf attracted crowds of bathers every summer to the Villepey-les-Bains temporary halt. Villepey Bridge No. 2 can be seen in the background (Pierre NICOLINI Collection).

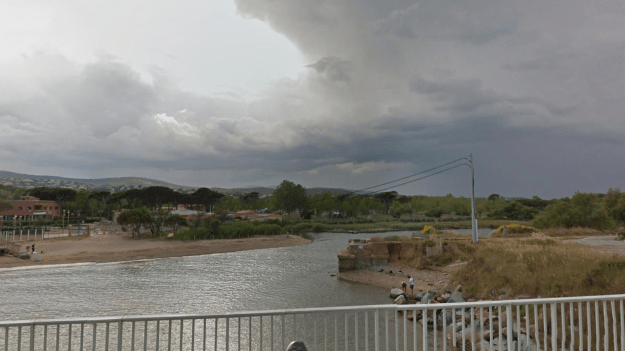

In this view from the modern road bridge, the more northerly abutment of the old railway bridge can still easily be seen. Soon after crossing these two bridge a third was encountered. The 3ème Pont de Villepey was a 12 metre span over a flood relief channel.

In this view from the modern road bridge, the more northerly abutment of the old railway bridge can still easily be seen. Soon after crossing these two bridge a third was encountered. The 3ème Pont de Villepey was a 12 metre span over a flood relief channel.

A rail accident close to St. Aygulf. I don’t have the date, any details of the accident or the circumstances that caused it.

A rail accident close to St. Aygulf. I don’t have the date, any details of the accident or the circumstances that caused it.

The beach at St. Aygulf in 1950.

The beach at St. Aygulf in 1950.

The beach in the 21st Century.

The beach in the 21st Century.

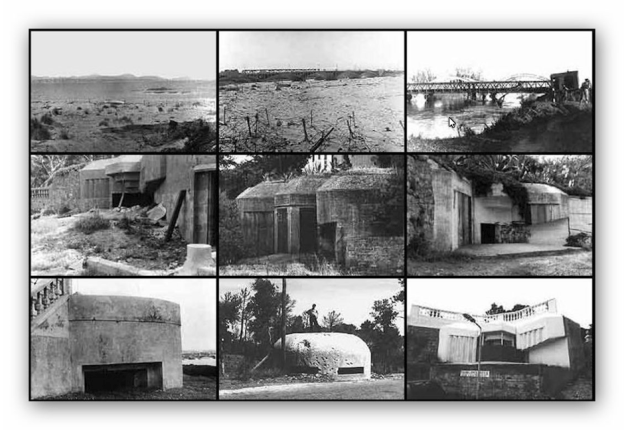

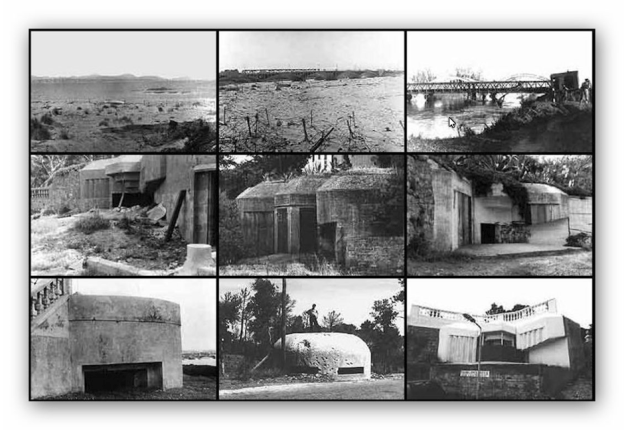

A compilation of images from the German fortifications, taken immediately after the Second World War are shown in the image below. Top middle is a view of the beach at St. Aygulf, top right is a view of the bridge over the Grand Argens.

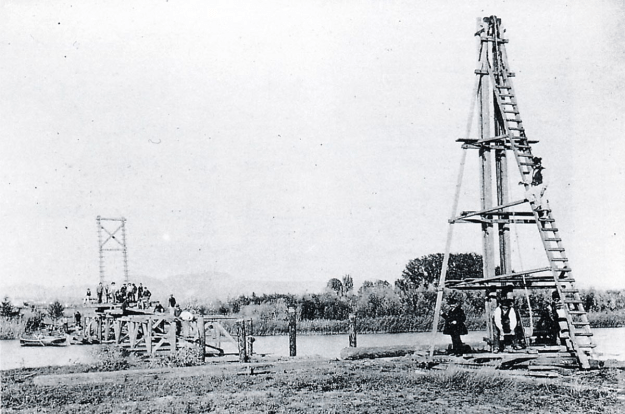

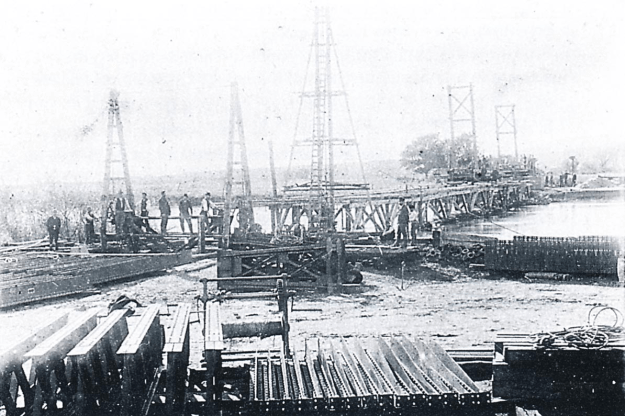

A short distance further along the line towards St. Raphael the railway had to cross the Grand Argens River. Gustave Eiffel constructed the bridge in 1888. In the first image temporary formwork has been erected prior to placing the permanent structure (Photo FERRARI – Edmond DUCLOS collection – GECP).

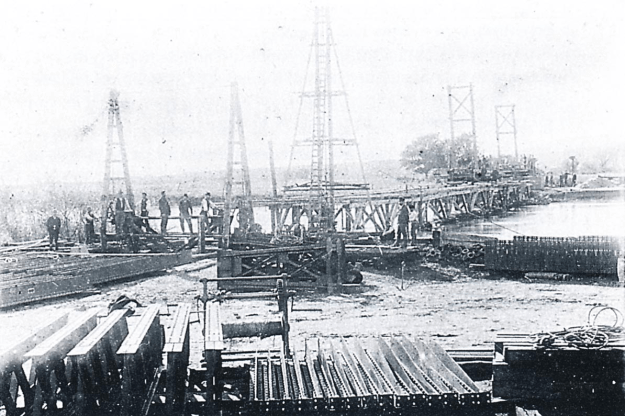

In this second image, further progress has been made. It shows the site after the flood of 6th September 1888. On the left, the two large frames of wood will be used as formwork for the construction of the abutments. In the centre, piles are being driven into the river bed. In the foreground we can see the metal elements which will be fabricated to make the bridge. There were three spans of 25 metres each (Photo FERRARI – Edmond DUCLOS collection – GECP).

In this second image, further progress has been made. It shows the site after the flood of 6th September 1888. On the left, the two large frames of wood will be used as formwork for the construction of the abutments. In the centre, piles are being driven into the river bed. In the foreground we can see the metal elements which will be fabricated to make the bridge. There were three spans of 25 metres each (Photo FERRARI – Edmond DUCLOS collection – GECP).

The completed bridge. The picture was taken in 1889 (GECP Collection).

The completed bridge. The picture was taken in 1889 (GECP Collection).

This final image of the Grand Argens Bridge shows it in a dilapidated state just before closure.

This final image of the Grand Argens Bridge shows it in a dilapidated state just before closure.

This road bridge is on the alignment of the old railway bridge.

This road bridge is on the alignment of the old railway bridge.

Within very short shrift the line crossed the Pont du Petit Argens. I have not been able to find many images of this bridge. The one below is displayed on Jean-Pierre Moreau’s webpage. In the autumn of 1888, a team of workers from the Gustave Eiffel company set out to set up the twelve (5 metre) metal spans that would form the bridge deck of the 60 m Pont du Petit Argens (Photo FERRARI – Edmond DUCLOS collection – GECP).

The old railway bridge was on the line of the present highway (D559) bridge.

The old railway bridge was on the line of the present highway (D559) bridge.

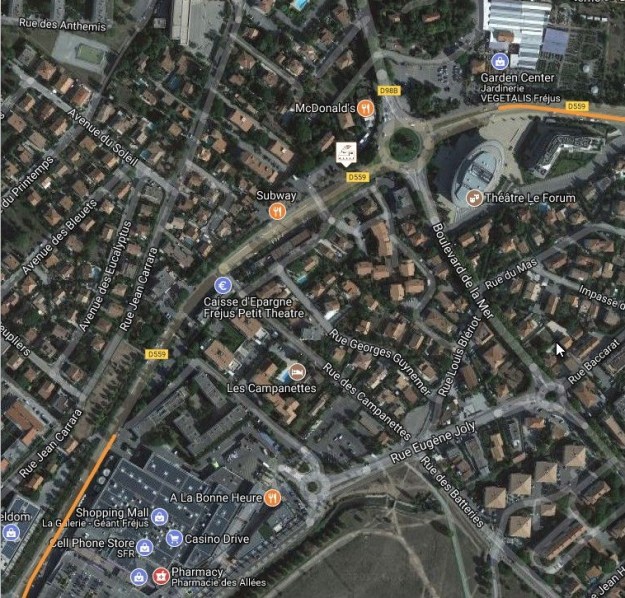

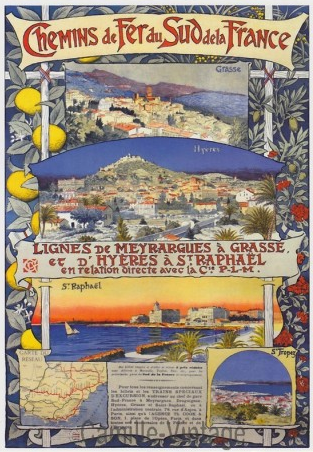

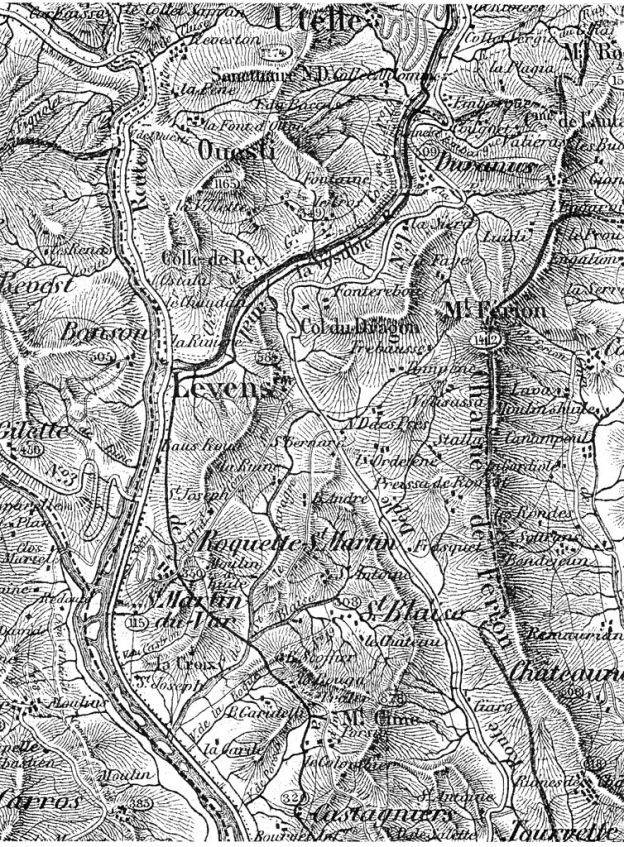

After crossing the canal the line travelled on the level to Frejus Station which was a small distance to the south-side of the small town of Frejus. We won’t stop here for any significant time as we are only 15 minutes or so from our final destination of St. Raphael just a little further along the coast. The first overhead image below is an aerial photograph of Frejus Station around the time of the closure of the line. Frejus is to the north of the station and was reached after crossing the coastal PLM line which is just out of shot at the top of the image.

The dominant line of trees marks the route of the present D98B. The well-defined white areas at the bottom right of the image are the aprons and taxiways of Frejus Airport.

An aerial photo of the airport can be seen below. The picture shows the airport in 1939 just before the start of the war.

This image is to approximately the same scale as the aerial photograph of the railway station and shows the same area in the 21st Century. The D559 follows the line of the old railway. Boulevard de la Mer follows the tree-lined road in the previous image of the station site. The Old PLM station just off the image to the North is now the SNCF station for Frejus.

This image is to approximately the same scale as the aerial photograph of the railway station and shows the same area in the 21st Century. The D559 follows the line of the old railway. Boulevard de la Mer follows the tree-lined road in the previous image of the station site. The Old PLM station just off the image to the North is now the SNCF station for Frejus.

We will have a quick look around the village/town of Frejus before returning to the station and then continuing our journey into St. Raphael. It is a place with a long history stretching back beyond Roman times and with evident archaeological sites from the Roman era.

The origins of Frejus probably lie with the Celto-Ligurian people who settled around the natural harbour of Aegytna. The remains of a defensive wall are still visible on Mont Auriasque and Cap Capelin. The Phoenicians of Marseille later established an outpost on the site.

Frejus was strategically situated at an important crossroads formed by the Via Julia Augusta (which ran between Italy and the Rhône) and the Via Domitiana. Although there are only few traces of a settlement at that time, it is known that the famous poet Cornelius Gallus was born there in 67 BC.[7, 9].

Julius Caesar wanted to supplant Massalia (ancient Marselles) and he founded the city as ‘Forum Julii’ meaning ‘market of Julius’; he also named its port ‘Claustra’. The exact date of the founding of Forum Julii is uncertain, but it was certainly before 43 BC since it appears in the correspondence between Plancus and Cicero. 49 BC is most likely.

Octavius repatriated the galleys taken from Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium here in 31 BCE.[10] and between 29 and 27 BCE, Forum Julii became a colony for his veterans of the eighth legion, adding the suffix Octavanorum Colonia.[11]

Augustus made the city the capital of the new province of Narbonensis in 22 BCE, spurring rapid development. It became one of the most important ports in the Mediterranean; its port was the only naval base for the Roman fleet of Gaul and only the second port after Ostia until at least the time of Nero.[12]

Subsequently, under Tiberius, the major monuments and amenities still visible today were constructed: the amphitheatre, the aqueduct, the lighthouse, the baths and the theatre. Forum Julii had impressive walls of 3.7 km length that protected an area of 35 hectares. There were about six thousand inhabitants. The territory of the city, extended from Cabasse in the west to Fayence and Mons in the north.

Frejus became an important market town for craft and agricultural production. Agriculture developed with villa rusticas such as at Villepey[13] and St. Raphael. Mining of green sandstone and blue porphyry and fish farming contributed to the thriving economy. In 40 CE Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who later completed the Roman conquest of Britain, was born in Forum Julii. He was father-in-law of the historian Tacitus, whose biography of Agricola mentions that Forum Julii was an “ancient and illustrious colony.”[14] The city was also mentioned several times in the writings of Strabo and Pliny the Elder.

In early 69 the Battle of Forum Julii was fought between the armies of the rival emperors Otho and Vitellius.[15] The exact location of this battle is not known, but afterwards Vitellius retreated to Antipolis.

The 4th century saw the creation of the diocese of Fréjus, France’s second largest after that of Lyon; the building of the first church is attested in 374 AD with the election of a bishop. Saint-Léonce became Bishop of Fréjus in 433 AD and wrote: “From 374 AD, at the Council of Valencia, a bishop was appointed in Frejus, but he never came. I was the first of the bishops of that city. I was able to build the first Cathedral with its Baptistry.”

An archaeological dig in July 2005[16] revealed a portion of ancient rocky coast which showed it was almost one kilometre further inland than current estimates. In the middle of the 1st century A.D. at the time of the creation of Forum Julii, this coastline was a narrow band of approximately 100m wide at the south of the Butte Saint-Antoine. This means that the ancient coast-line would have approximated to the line of the Chemin de Fer du Sud de la France. Further recent archaeology has revealed much information on the ancient port.[17]

A Triton monument was discovered at the entrance to the harbour. This statue and the remains of a Roman building at the end of the eastern quay nearby, shows this site to be a lighthouse. Two lighthouses were constructed on the quays and a third assisted mariners in locating the harbour’s sea entrance. The third, situated on the Île du Lion de Mer, would have been the primary beacon that ships would have navigated toward. As ships approached the harbour, the Triton lighthouse on the northern side of the channel into the harbour and the other lighthouse on the southern side would have marked the entrance and thus provided safe passage into the harbour.

The ruins of one of these lighthouses can be seen just to the North of the site of the old station.

The ruins of one of these lighthouses can be seen just to the North of the site of the old station.

Wandering north from the Butte Saint-Antione, we very quickly reach the old Town of Frejus.

The PLM/SNCF railway runs across the bottom half of the satellite image. The rebuilt Roman amphitheatre is easily seen on the top left and the tight-knit streets of the old town fill the right half of the image. The Chemin de Fer du Sud Line was just off the southern edge of this photograph.

The amphitheatre has been significantly ‘improved’. A new facility sits within the old walls.

The old amphitheatre has been cloaked in a modern concrete shell to make a local venue. You could argue that it has been vandalised! The work was undertaken in 2012.

The old amphitheatre has been cloaked in a modern concrete shell to make a local venue. You could argue that it has been vandalised! The work was undertaken in 2012.

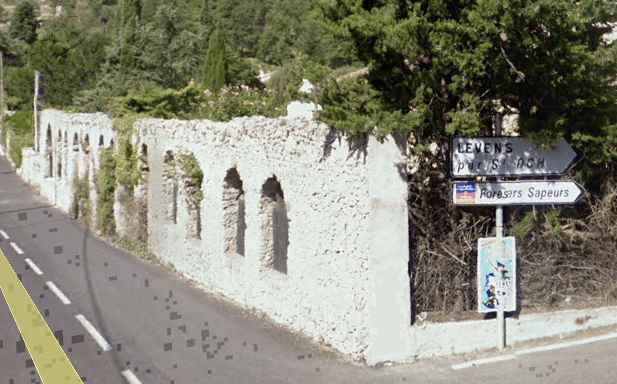

In addition to the amphitheatre, the town also has the remains of several pillars of a 20 mile long aqueduct; portions of a theatre; two gates – La Porte d’Oree and Porte des Gauls; a tower signifying the entrance to the harbor, Augustus’ Lantern; and Roman ramparts. The aqueduct was to the east of Frejus and brought water from the nearby hills.

Various Roman antiquities, including the gates and aqueducts and parts of the old forum.

Frejus declined significantly in the Middle Ages, from a city of upwards of 10,000 to a population of perhaps no more than 1500. Nevertheless the cathedral is a significant building.

The town today has a population of around 50,000 people. In the middle of the 20th Century it experienced a catastrophic event, the failure of a dam further up the valley of the River Reyran. The Malpasset Dam was built between 1952 and 1954. On 2nd December 1959, it failed.

The Dam was 7km north of Fréjus. It was a doubly curved, equal angle arch type with variable radius.

The Dam was 7km north of Fréjus. It was a doubly curved, equal angle arch type with variable radius.

Shortly after 9 pm on 2nd December 1959, the dam failed and pieces of the dam can still be seen today scattered throughout the area. The breach created a massive wave, 40 m high, moving at 70 kilometres per hour. It destroyed two small villages, Malpasset and Bozon, a highway construction site nearby and 20 minutes later reached Fréjus. The wave was still 3 metres high. Various small roads and railroad tracks were destroyed on the way, water flooded the western half of Fréjus town before finally reaching the sea.

Malpasset Dam was meant to supply a steady stream of water for irrigation in a region where summers are dry and rains capricious. Under the stress of a vicious downpour of seasonal rains and probably due to fissures in the rock that supported its foundation, the dam collapsed.

The inquiry noted that in the weeks before the breach, some cracking noises had been heard, though not properly checked. In November 1959 minor leaks started to appear in the dam.

Between 19th November and 2nd December 1959, the area had 50 cm of rainfall, in the last 24 hours before the breach alone, 13 cm were recorded. The water level in the dam was only 28 cm away from the top. As rains continued, the site manager wanted to open the discharge valves, but the authorities refused, claiming the highway construction site wuld be a risk of flooding. Just 3 hours before the breach, at around 6 pm, the water release valves were opened, but a discharge rate of 40 m³/s was unfortunately not enough to empty the reservoir in time.

The damage to the valley, to the villages and to the town of Fréjus was significant. The tragedy cost the lives of 423 people. Contemporary and more recent photos follow.

The Dam as built in 1954.

The Dam as built in 1954.

Malpasset Dam in the 21st Century.

Malpasset Dam in the 21st Century.

The dam bust of 1959 was devastating for the town of Fréjus and as can easily be seen in the later pictures it had a significant effect on the town’s railways. By 1959, the Chemin de Fer du Sud was closed and the pictures all show the standard Gauge SNCF line.

There is a presentation about the dam failure available on-line at https://prezi.com/zzwjemmlvyeb/malpasset-dam.%5B19%5D

Films about the dam failure can be found at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9_61-wGFlcc, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ud2P4hPhEtY and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JZm4MWYDOO8.%5B20%5D

A full detailed report on the failure can be found at https://www.aria.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/wp-content/files_mf/FD_29490_malpasset_1959_ang.pdf.%5B21%5D

It is with some sense of sadness that we turn away from the tragedy of 1959 and finish wandering around the town before heading south to the station.

A final look at some Roman ruins before crossing the SNCF/PLM Railway Line.

A final look at some Roman ruins before crossing the SNCF/PLM Railway Line.

The SNCF Station in Frejus in 21st Century and inn earlier years ….

The SNCF Station in Frejus in 21st Century and inn earlier years ….

And then back to the Chemin de Fer du Sud Station just a little further south. When we arrive we have a few moments to notice a minor accident at the turntable in the station which took place on 28th April 1907.

An 0-6-0T Pinguely Series 41-44 was erroneously directed into the depot area while the turntable was aligned to allow cleaning. There was a fatality. A postal employee perished in his van which was caught between the loco and the first passenger coach of the train. Incidentally, these locomotives were altered not long after this picture was taken to add a front bogie and become 2-6-0T locos (Raymond BERNARDI Collection)

An 0-6-0T Pinguely Series 41-44 was erroneously directed into the depot area while the turntable was aligned to allow cleaning. There was a fatality. A postal employee perished in his van which was caught between the loco and the first passenger coach of the train. Incidentally, these locomotives were altered not long after this picture was taken to add a front bogie and become 2-6-0T locos (Raymond BERNARDI Collection)

The body of the mixed bogie car AB-1016 (future 2506) Buire, has run through into the postal van. The coach was at this time covered with teak slats, simply varnished (Michel FRANCHITTI Collection).

The body of the mixed bogie car AB-1016 (future 2506) Buire, has run through into the postal van. The coach was at this time covered with teak slats, simply varnished (Michel FRANCHITTI Collection).

The people of Frejus came out in large numbers to see the accident. Inaddition to seeing the crowd we can also pick out key buildings at the station in this image – the engine shed and water tower are at the rea of the image (Pierre NICOLINI Collection).

The people of Frejus came out in large numbers to see the accident. Inaddition to seeing the crowd we can also pick out key buildings at the station in this image – the engine shed and water tower are at the rea of the image (Pierre NICOLINI Collection).

The station layout shows the location of the turntable which features in the accident in the pictures above. We have some time before the next train arrives and so can have a good look around the station and its vicinity. The station opened in 1889. It included 2nd Class Station facilities with a goods shed, an engine shed capable of stabling two locos, repair shops, two main tracks and a goods track and a water tower. In 1900, the engine shed was enlarged to accommodate four locomotives. Little remains of the station. Many of its buildings were demolished in 1966 and between Fréjus and St.Raphaël, the line is now used by cars, under the names of Avenue de Provence and Avenue Victor Hugo (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

The station layout shows the location of the turntable which features in the accident in the pictures above. We have some time before the next train arrives and so can have a good look around the station and its vicinity. The station opened in 1889. It included 2nd Class Station facilities with a goods shed, an engine shed capable of stabling two locos, repair shops, two main tracks and a goods track and a water tower. In 1900, the engine shed was enlarged to accommodate four locomotives. Little remains of the station. Many of its buildings were demolished in 1966 and between Fréjus and St.Raphaël, the line is now used by cars, under the names of Avenue de Provence and Avenue Victor Hugo (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

In this view, we see a mixed train heading to Hyères and Toulon (Jean-Paul PIGNEDE Collection).

In this view, we see a mixed train heading to Hyères and Toulon (Jean-Paul PIGNEDE Collection).

The passenger station building was not demolished until 1996 when it was removed to make way for a fast food restaurant (Photo Guy MEYNEUF).

The passenger station building was not demolished until 1996 when it was removed to make way for a fast food restaurant (Photo Guy MEYNEUF).

One bay of the loco shed has been converted into a garage by the Departmental Directorate of Equipment (Photo Equipment José BANAUDO).

One bay of the loco shed has been converted into a garage by the Departmental Directorate of Equipment (Photo Equipment José BANAUDO).

A major fire destroyed the workshop building on 19th May 1948. Five railcars were destroyed, including the four new Renault 215-Ds, but also all the parts needed to maintain railcars across the system (GECP Collection).

A major fire destroyed the workshop building on 19th May 1948. Five railcars were destroyed, including the four new Renault 215-Ds, but also all the parts needed to maintain railcars across the system (GECP Collection).

The former locomotive workshop was converted into a depot for road services serving the Var coast. Here we see two Renault 215-D and R-4190 coaches from CP in 1955. (Photo Paul CARENCO).

The former locomotive workshop was converted into a depot for road services serving the Var coast. Here we see two Renault 215-D and R-4190 coaches from CP in 1955. (Photo Paul CARENCO).

We are left with a reasonably rich portfolio of photographs of locomotives and railcars at Frejus. These images follow.

2-4-2T locomotive No. 56 when it left the SACM factory in Belfort in April 1889 had represented the Sud-France company at the World Fair in Paris, before entering service on the Littoral line. Here its sister 2-4-2T No. 53 is seen on the tracks of the depot at Fréjus (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

2-4-2T locomotive No. 56 when it left the SACM factory in Belfort in April 1889 had represented the Sud-France company at the World Fair in Paris, before entering service on the Littoral line. Here its sister 2-4-2T No. 53 is seen on the tracks of the depot at Fréjus (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

2-6-0T Pinguely No. 44 locomotive in August 1947 stabled out of service at the Fréjus depot (José BANAUDO Collection).

2-6-0T Pinguely No. 44 locomotive in August 1947 stabled out of service at the Fréjus depot (José BANAUDO Collection).

During the summer of 1948, 4-6-0T Pinguely No. 66 locomotive was parked in front of a Brissonneau & Lotz railcar at the Fréjus depot; in the background it is [possible to pick out the fire-damaged diesel workshop, now without its roof (Photo Jean MONTERNIER – François COLLARDEAU collection).

During the summer of 1948, 4-6-0T Pinguely No. 66 locomotive was parked in front of a Brissonneau & Lotz railcar at the Fréjus depot; in the background it is [possible to pick out the fire-damaged diesel workshop, now without its roof (Photo Jean MONTERNIER – François COLLARDEAU collection).

Two locomotives stabled out of service at the Fréjus depot after the Second World War: 2-6-0T Pinguely No. 43 in front of the 4-6-0T Pinguely No. 65 in August 1949 (Jean-Pierre VERGEZ-LARROUY Collection).

Two locomotives stabled out of service at the Fréjus depot after the Second World War: 2-6-0T Pinguely No. 43 in front of the 4-6-0T Pinguely No. 65 in August 1949 (Jean-Pierre VERGEZ-LARROUY Collection).

Moreau says that this is a Brissonneau & Lotz Autorail train under test prior to export, pictured in front of the goods shed at Frejus in December 1939 (Photo Pierre BARRY).

Moreau says that this is a Brissonneau & Lotz Autorail train under test prior to export, pictured in front of the goods shed at Frejus in December 1939 (Photo Pierre BARRY).

The Littoral network was closed for a variety of reasons, but not because of a lack of travellers! This excursion train, seen in Fréjus, consists of a Brissonneau & Lotz railcar, a “jardinière” loaded with passengers and bicycles, and a wooden car; the building of the diesel workshop can be seen in the background. As this caught fire in May 1948, this image is taken before that date (Gérard COMELAS collection).

The Littoral network was closed for a variety of reasons, but not because of a lack of travellers! This excursion train, seen in Fréjus, consists of a Brissonneau & Lotz railcar, a “jardinière” loaded with passengers and bicycles, and a wooden car; the building of the diesel workshop can be seen in the background. As this caught fire in May 1948, this image is taken before that date (Gérard COMELAS collection).

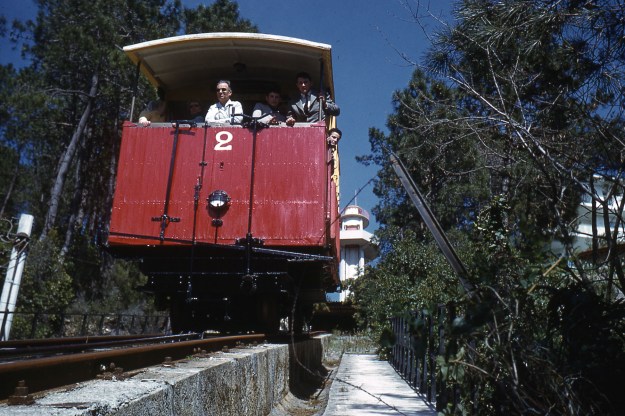

At Easter 1951, nearly three years after the closure of the network, Brissonneau & Lotz await their fate at the depot at Fréjus. They are fortunate in that they will not be broken up as they have been sold for use in Spain. On the left is a wagon chassis of the Tramways Alpes-Maritimes (TAM) used as flat car, and on the right motors ZM-5 and 9 burned out (Paul CARENCO Collection).

At Easter 1951, nearly three years after the closure of the network, Brissonneau & Lotz await their fate at the depot at Fréjus. They are fortunate in that they will not be broken up as they have been sold for use in Spain. On the left is a wagon chassis of the Tramways Alpes-Maritimes (TAM) used as flat car, and on the right motors ZM-5 and 9 burned out (Paul CARENCO Collection).

Also taken in 1951 (Photo Paul CARENCO).

Also taken in 1951 (Photo Paul CARENCO).

After the closure of the network, the railcars Brissonneau & Lotz remained parked for three years at the Frejus depot while waiting to find a new job. An unidentified train is shown next to a 2-6-0T Pinguely locomotive series 41 to 44 (Hidalgo ARNERA Collection).

After the closure of the network, the railcars Brissonneau & Lotz remained parked for three years at the Frejus depot while waiting to find a new job. An unidentified train is shown next to a 2-6-0T Pinguely locomotive series 41 to 44 (Hidalgo ARNERA Collection).

In August 1949 the trailers ZR-6 and 14 form a large double trailer (Jean-Pierre VERGEZ-LARROUY Collection).

In August 1949 the trailers ZR-6 and 14 form a large double trailer (Jean-Pierre VERGEZ-LARROUY Collection).

Another Brissonneau & Lotz railcar parked in front of the old diesel workshop of Fréjus, in ruins after his fire (Hidalgo ARNERA Collection).

Another Brissonneau & Lotz railcar parked in front of the old diesel workshop of Fréjus, in ruins after his fire (Hidalgo ARNERA Collection).

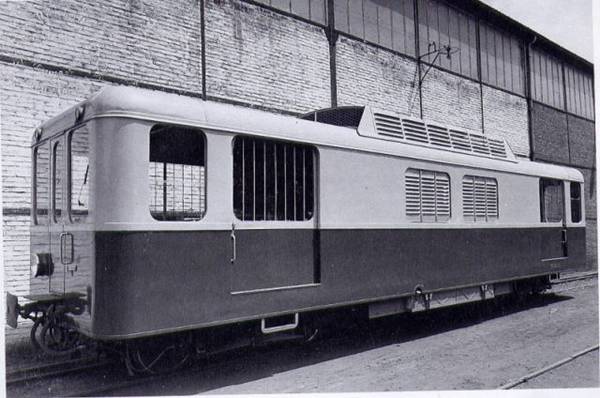

We have seen everything we can at Frejus and so get on the next train to Saint-Raphael. Typical of the railcars on this line is the model in the picture below. It is more likely that the railcars on the line were coloured grey and blue, rather than cream and blue.

The railway line left Frejus station travel in an easterly direction. The route is now covered by the D559, Avenue de Provence. There was a halt on the line – Frejus-Plage only a short distance from St. Raphael.

Just before reaching the PLM railway line the Chemin de Ferdu Sud crossed a river bridge – Pont du Pédégal. The bridge has been replaced by this road bridge.

The line then passed under the PLM/SNCF main-line before rising on a relatively steep grade up to the level of the PLM/SNCF track in Saint-Raphael Station, crossing another river bridge on the way – Pont de la Garonne.

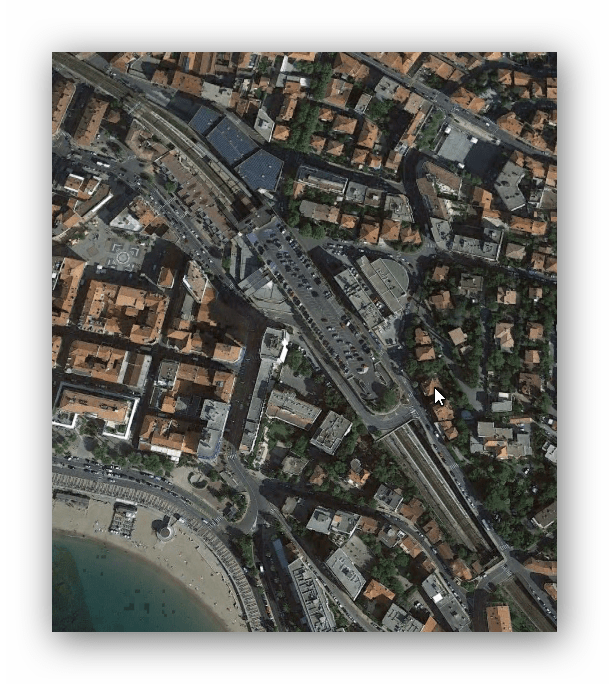

These two aerial images are taken in 1945 and show the last few hundred metres of the railway line that we have been following. The second focusses on the joint station at St. Raphael.

As we leave our train we have a good look around St. Raphael Station.

Both PLM (right) and SF (left) stations faced each other at St. Raphael (Jean BAZOT Collection).

Around 1905, a PLM Marseille to Nice train enters the station of St. Raphael, where connecting travellers have only two tracks to cross from SF station, on the right (Hidalgo ARNERA Collection).

Around 1905, a PLM Marseille to Nice train enters the station of St. Raphael, where connecting travellers have only two tracks to cross from SF station, on the right (Hidalgo ARNERA Collection).

At the eastern end of the St. Raphael station, the transit wharf and a 6-ton crane allowed for the transhipment of goods (sleepers, props and wine barrels) between the Chemin de Fer du Sud wagons (on the right ) and those of the PLM, or vice versa (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

At the eastern end of the St. Raphael station, the transit wharf and a 6-ton crane allowed for the transhipment of goods (sleepers, props and wine barrels) between the Chemin de Fer du Sud wagons (on the right ) and those of the PLM, or vice versa (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

We have on record a few images of locomotives, railcars and rolling stock from the Chemin de Fer du Sud when at St. Raphael. A number of these follow.

The loading of locomotive 0-4-0 + 0-4-0T SACM No. 32 onto a PLM Wagon at St. Raphaël on 17th January 1935. It is being returned to a metre gauge system in the Alps. The chimney, the valves, the steam dome casing and the cabin were dismantled so as not to exceed the loading gauge or foul other rail furniture along the way (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – GECP collection).

The loading of locomotive 0-4-0 + 0-4-0T SACM No. 32 onto a PLM Wagon at St. Raphaël on 17th January 1935. It is being returned to a metre gauge system in the Alps. The chimney, the valves, the steam dome casing and the cabin were dismantled so as not to exceed the loading gauge or foul other rail furniture along the way (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – GECP collection).

Mixed car AB-2531 (ex-1031) Hanquet-Aufort seen in 1937 at St. Raphaël was repainted in blue and grey to be used as a trailer behind the railcars Brissonneau & Lotz (José BANAUDO Collection).

Mixed car AB-2531 (ex-1031) Hanquet-Aufort seen in 1937 at St. Raphaël was repainted in blue and grey to be used as a trailer behind the railcars Brissonneau & Lotz (José BANAUDO Collection).

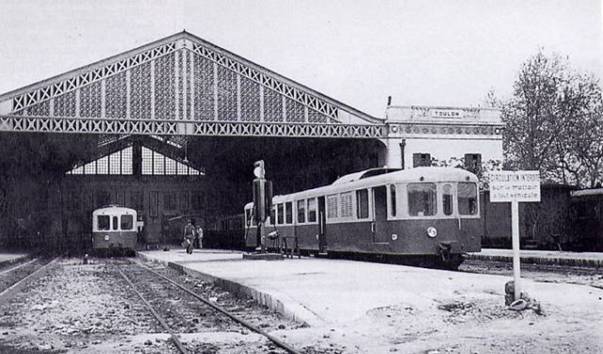

Brissonneau & Lotz ZM + ZR-1 and 2 of the Railroad and Port of Reunion (CPR), stabled at St. Raphael during testing in December 1939 (Collection Bernard Roze).

Brissonneau & Lotz ZM + ZR-1 and 2 of the Railroad and Port of Reunion (CPR), stabled at St. Raphael during testing in December 1939 (Collection Bernard Roze).

During the tests of the first Brissonneau & Lotz railcars in the spring of 1935, a group of railway workers gathered at the St. Raphael station. The operational staff are in caps and in the jackets with double row of buttons, while the drivers and workshop staff (from Fréjus) wear working outfits or more informal civilian clothes (René CLAVAUD Collection).

During the tests of the first Brissonneau & Lotz railcars in the spring of 1935, a group of railway workers gathered at the St. Raphael station. The operational staff are in caps and in the jackets with double row of buttons, while the drivers and workshop staff (from Fréjus) wear working outfits or more informal civilian clothes (René CLAVAUD Collection).

New Brissonneau & Lotz railcar at the Chemin de Fer du Sud platform at St.Raphaël (GECP Collection).

New Brissonneau & Lotz railcar at the Chemin de Fer du Sud platform at St.Raphaël (GECP Collection).

On 29th August 1941, a Brissonneau & Lotz railcar sits at the Western end of the platform in St. Raphael Station. It is waiting for the connection with a train on the PLM railway between Marseille and Ventimiglia; in the foreground, we can see the SNCF standard gauge track and on the left a “butterfly,” a small reflectorized signal indicating the position of the point at the station (Photo Michel DUPONT-CAZON).

On 29th August 1941, a Brissonneau & Lotz railcar sits at the Western end of the platform in St. Raphael Station. It is waiting for the connection with a train on the PLM railway between Marseille and Ventimiglia; in the foreground, we can see the SNCF standard gauge track and on the left a “butterfly,” a small reflectorized signal indicating the position of the point at the station (Photo Michel DUPONT-CAZON).

Milk churns and other packages are being unloaded from the Brissonneau & Lotz ZM-3 + ZR-8 railcar at St.Raphaël station around 1947 (FACS-UNECTO collection).

Milk churns and other packages are being unloaded from the Brissonneau & Lotz ZM-3 + ZR-8 railcar at St.Raphaël station around 1947 (FACS-UNECTO collection).

The next two images are of the Chemin de Fer du Sud station building after closure of the line. The first shows St. Raphaël station with a Renault R-4190 coach after the station has been commandeered to be used for road transport (Photo Marcel CAUVIN).

The second shows the station building being demolished in 1958. Nowadays, this location is occupied by the bus station (Pierre NICOLINI collection).

The second shows the station building being demolished in 1958. Nowadays, this location is occupied by the bus station (Pierre NICOLINI collection).

The satellite image shows the station site in the 21st Century.

We also have plan views which show the station at its fullest extent and later in 1945.

And finally, we head out of the station onto the concourse and into St. Raphael.

And finally, we head out of the station onto the concourse and into St. Raphael.

The immediate vicinity of St. Raphael saw human activity at least as far back as Neolithic times. The shipwrecks that cover the seabed in the region provide evidence that the region was a prominent Roman commercial hub. When Fréjus was called Forum Julii and when Caesar ruled the Mediterranean, Saint-Raphaël was a renowned seaside resort. Epulias, as it was once called, welcomed some of the wealthiest Roman families during the summer!

In the Middle Ages, after a period of chaos and plundering, the region was at peace again in the 4th Century. It was during this time that Saint Honorat lived as a hermit in what is now known as the Saint Honorat cave before his exile to the “Iles de Lérins” in the bay of Cannes where he founded his monastery. His presence made the town an important pilgrimage destination.

St. Raphael’s coat of arms dates back to a period from 16th to 18th Centuries. It shows Raphael the Archangel accompanied by a young man named Tobie or Tobit. It is believed that Raphael saved Tobie’s father from blindness, and this legend explains the origin of the name of the city!

In 1794, just after the revolution, Saint-Raphael briefly changed its name to Barraston, after Barras, one of the members of the first government. After his Egyptian campaign, Saint-Raphaël welcomed the Emperor Bonaparte. Ironically, he would return one more time for his departure on his way to exile on Elbe Island.

The end of the 19th century is when Saint-Raphaël began to look as it does today. The city prospered thanks to commercial activity which included the exportation of ceramics, rocks and cork. Felix Martin, a famous engineer and former student of the “Ecole Polytechnique”, raised the city to the standards of a modern seaside resort. The Casino was built along with numerous Palladian style villas. The basilica, Notre Dame de la Victoire, with its unique Byzantine style, was built in the same period by the architect Pierre Aublé.

The construction of the PLM railway line gave Saint-Raphaël another opportunity to accelerate its development as a tourist destination. It also attracted many artists who come to enjoy the climate and the scenery. People like Gounot, Georges Sand and Maupassant spent time in Saint-Raphael.

In the 20th Century St. Raphael and its immediate area played a significant part in the Allied invasion of Europe when American troops landed at various beaches along the coast including Dramont on 15th August 1944. Today, Saint-Raphaël is one of the most popular seaside resorts, and it accommodates the highest number of visitors in the Var region.

Postcript: In November 2018, my wife and I had 10 days staying in Saint-Raphael. On 13th November, we wandered through the town for the first time. The modern station building is, in my view, ugly. It would have been far better for the town to have renovated the old buildings of the station and modified then for modern usage. We were able to wander along the area below the arches which supported the metre-gauge line. This arches have been renovated and modernised and provide space for interesting small retail businesses.

The pictures below show first, the station; then the arches and road-under bridge which used to support the old line, as they are today, and the abutments of the river bridge!

We also enjoyed following the old line on 14th November through Frejus to Ste Maxime, but I have not supplemented the above pictures here.

We also enjoyed following the old line on 14th November through Frejus to Ste Maxime, but I have not supplemented the above pictures here.

References

[1] Roland Le Corff; http://www.mes-annees-50.fr/Le_Macaron.htm, accessed 13th December 2017.

[2] Marc Andre Dubout; http://marc-andre-dubout.org/cf/baguenaude/toulon-st-raphael/toulon-st-raphael3.htm, accessed 4th January 2018.

[3] Jean-Pierre Moreau; http://moreau.fr.free.fr/mescartes/ToulonGareSudFrance.html, accessed 24th December 2017.

[4] José Banaudo; Histoire des Chemins de Fer de Provence – 2: Le Train du Littoral (A History of the Railways of Provence Volume 2: The Costal Railway); Les Éditions du Cabri, 1999.

[5] https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sainte-Maxime, accessed 5th January 2018.

[6] Roger Farnworth; https://rogerfarnworth@wordpress.com.

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fréjus, accessed 12th January 2018.

[8] Pala Sen; https://trip101.com/article/best-things-to-do-in-frejus-france, accessed 12th January 2018.

[9] Ronald Syme; The Origin of Cornelius Gallus; The Classical Quarterly, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Vol. 32, No. 1 January 1938 , p. 39-44.

[10] Tacitus Annals IV, 5

[11] Pliny the Elder, Histories, III, 35

[12] Tacitus Histories 2, 14; 3, 43

[13] A. Donnadieu; Les fouilles des ruines gallo-romaines de Villepey (Villa Podii). Près Fréjus (Forum Julii); Institut des fouilles de Provence et des préalpes. Bulletin et Mémoires, 1926-1928,

[14] Tacitus Histories 3, 43

[15] Tacitus: Histories 2.14-15.

[16] Pierre Excoffon, Benoît Devillers, Stéphane Bonnet et Laurent Bouby; New data on the position of the ancient shoreline of Fréjus. The archaeological diagnosis of the “théâtre d’agglomération” (Fréjus, Var); http://archeosciences.revues.org/59.

[17] Chérine Gébara & Christophe Morhange; Fréjus (Forum Julii): Le Port Antique/The Ancient Harbour; Journal of Roman Archaeology, Portsmouth, R.I. 2010.

[18] G. Mann; Locating Colonial Histories: Between France and West Africa; The American History Journal. 110 (5): April 2005, p409–434.

[19] Pavlo Besedin https://prezi.com/zzwjemmlvyeb/malpasset-dam on 25 November 2013, accessed 13th January 2018.

[20] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9_61-wGFlcc, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ud2P4hPhEtY, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JZm4MWYDOO8 on http://damfailures.org/case-study/malpasset-dam-france-1959, accessed 13th January 2018.

[21] French Ministry for Sustainable Development – DGPR / SRT / BARPI; https://www.aria.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/wp-content/files_mf/FD_29490_malpasset_1959_ang.pdf

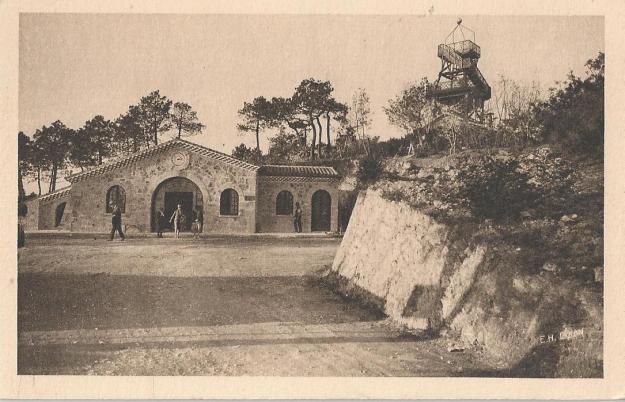

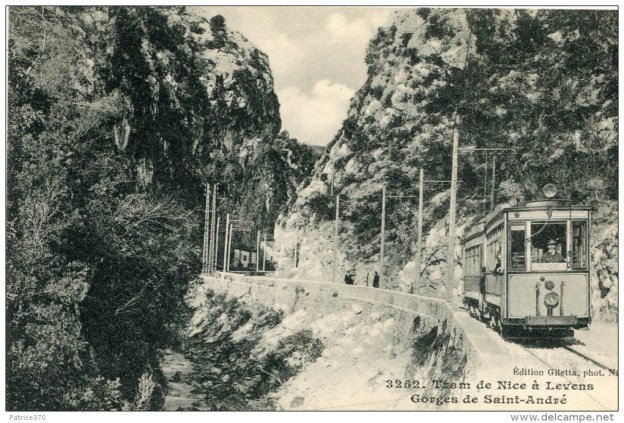

This picture shows the lower station as it is in the early 21st Century. The Observation Tower can be seen on the distant horizon at the top right of the image.

This picture shows the lower station as it is in the early 21st Century. The Observation Tower can be seen on the distant horizon at the top right of the image.

The replacement bridge was not built until 1953, by which time, in this scenario, the trams were long gone!

The replacement bridge was not built until 1953, by which time, in this scenario, the trams were long gone!

There were small deviations in the route of the tramway from the modern M19, although most of these were very short, only a matter of a few metres, and were usually the result of engineers seeking a path for the wider, newer road. This is true at La Clue, shown above.

There were small deviations in the route of the tramway from the modern M19, although most of these were very short, only a matter of a few metres, and were usually the result of engineers seeking a path for the wider, newer road. This is true at La Clue, shown above.

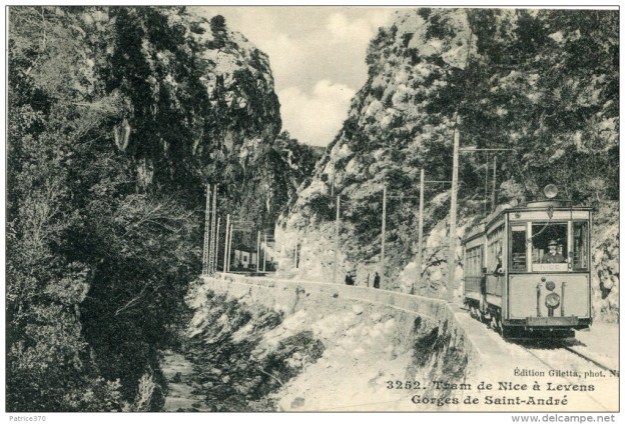

The shoreline was itself a tourist object: the panorama of the Mediterranean and the villages did not lack charm. On the heights of Beaulieu, the tram takes the pose with a platform abundantly stocked for the occasion.

The shoreline was itself a tourist object: the panorama of the Mediterranean and the villages did not lack charm. On the heights of Beaulieu, the tram takes the pose with a platform abundantly stocked for the occasion. Another view of the coast line with a motor-tram running on the Corniche at Villefranche sur Mer. The road was still made only of dirt and gravel, and in the shadow of the tramway there is a cart pulled either by a donkey or by a horse.

Another view of the coast line with a motor-tram running on the Corniche at Villefranche sur Mer. The road was still made only of dirt and gravel, and in the shadow of the tramway there is a cart pulled either by a donkey or by a horse. An attempt to provide a reversible train with two motor-trams framing a trailer-car on the line of Monte-Carlo. The power of the leading motor-tram proved to be inadequate for the load.

An attempt to provide a reversible train with two motor-trams framing a trailer-car on the line of Monte-Carlo. The power of the leading motor-tram proved to be inadequate for the load.  10 Schneider Type H buses similar to the one above were purchased. They were similar to those in use in Paris. They arrived in Nice in 1925. They were followed in a short period of time by 3 Somua MAT2 buses.

10 Schneider Type H buses similar to the one above were purchased. They were similar to those in use in Paris. They arrived in Nice in 1925. They were followed in a short period of time by 3 Somua MAT2 buses.

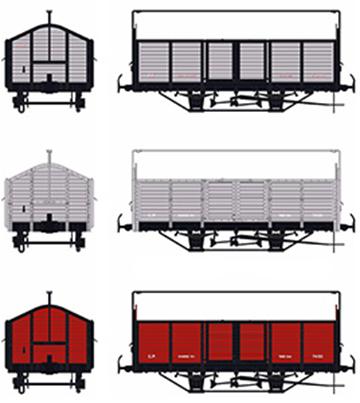

G 20x – Buire 1911

G 20x – Buire 1911

The beach at Sainte-Maxime in 1938. The new road bridge is visible in the top right of the picture. This scene would change dramatically over the next few years and ultimately this would be one on the invasion beaches in 1944.

The beach at Sainte-Maxime in 1938. The new road bridge is visible in the top right of the picture. This scene would change dramatically over the next few years and ultimately this would be one on the invasion beaches in 1944.

The halt was very close to the sea wall, as this image makes clear. The gates to the right of the picture have long-gone but gave access onto an estate which was owned by a German family – the Kronprinz estate. The railway continued off to the right of the picture above the sea wall.

The halt was very close to the sea wall, as this image makes clear. The gates to the right of the picture have long-gone but gave access onto an estate which was owned by a German family – the Kronprinz estate. The railway continued off to the right of the picture above the sea wall.