In the featured image above La Foux des Pins is in the bottom left and Sainte Maxime in the top right .

.

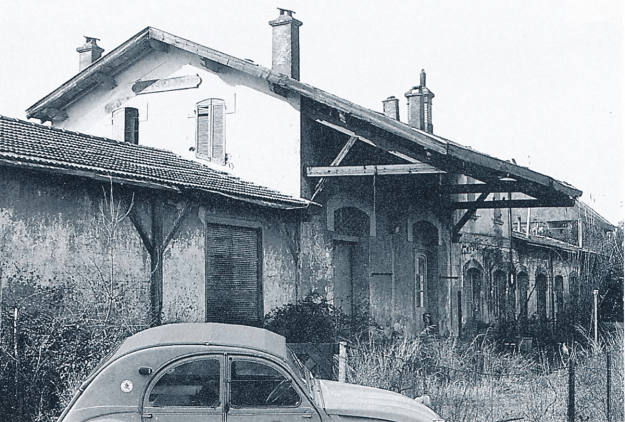

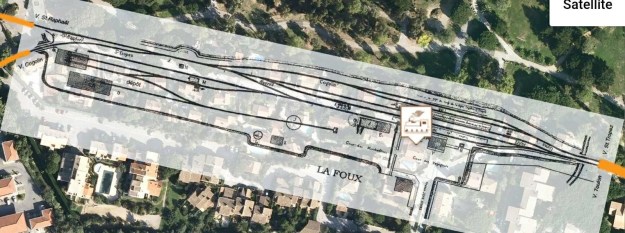

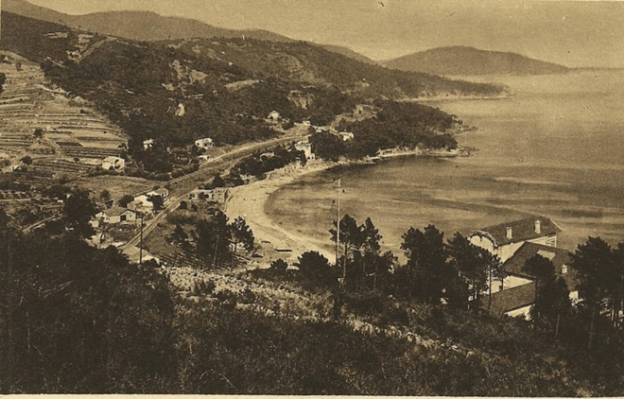

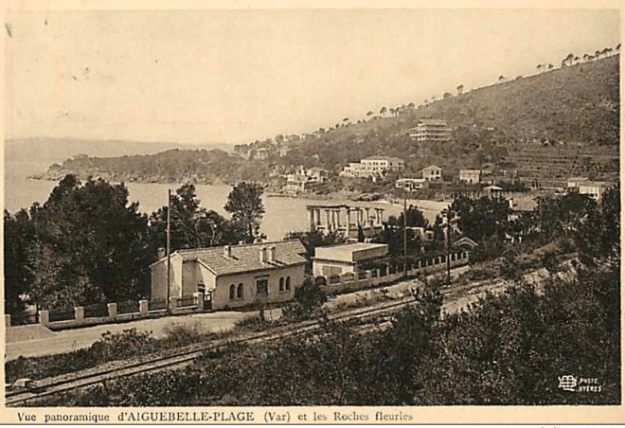

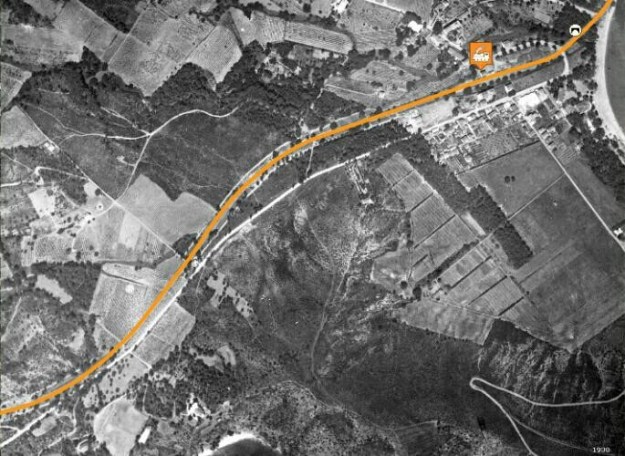

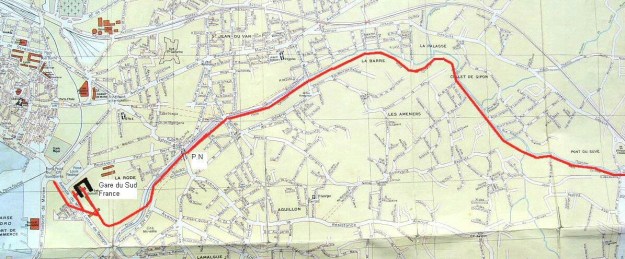

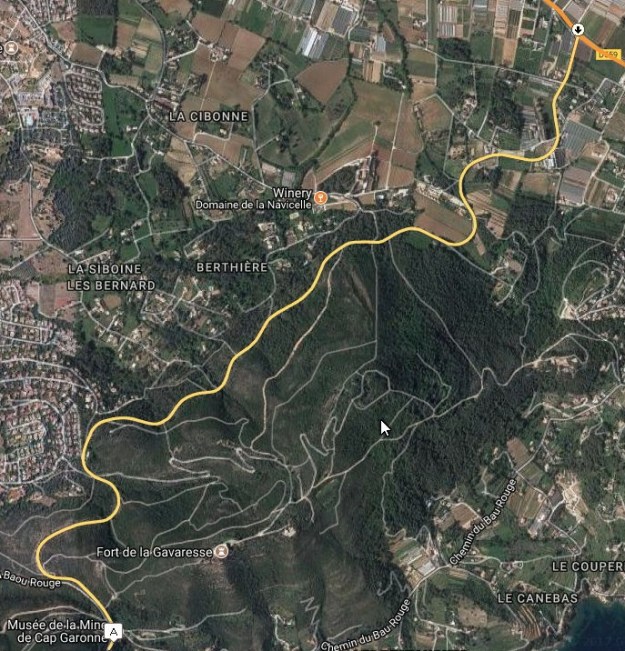

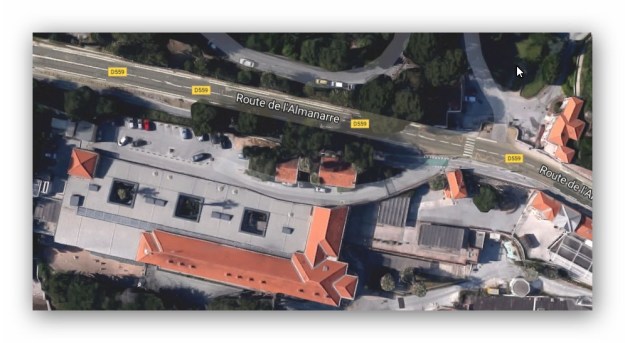

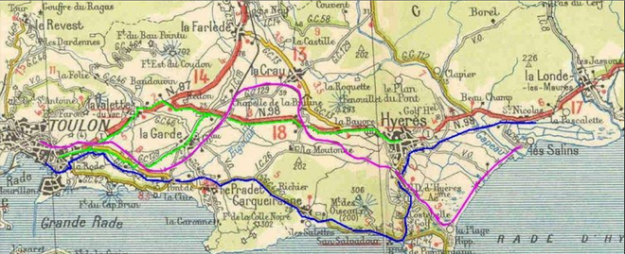

Having enjoyed two diversions from the mainline[5],[6], we return to La Foux ready to travel on towards St. Raphael. Before setting off, there is time to look round the station and its immediate environment. The village and station are sat on the south side of the Golfe de St. Tropez close to the River Giscle estuary and what were once wide-open sand flats. The satellite image with the route of the railway and a series of aerial photos which comes from Jean-Pierre Moreau[3] allow us to orient ourselves once again.

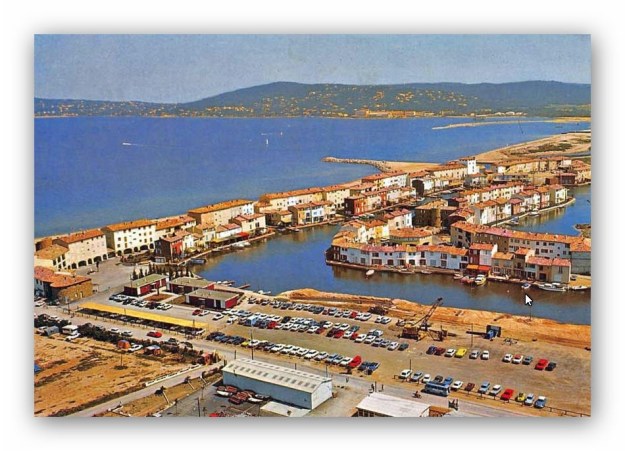

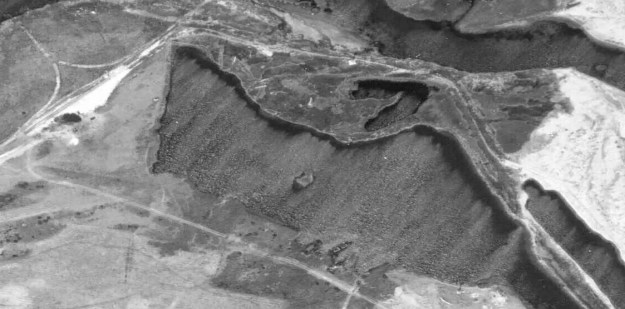

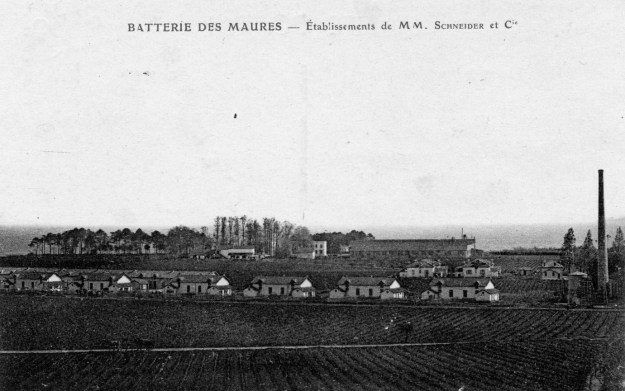

North of La Foux is the modern village of Port Grimaud. It is built on an area that was once used to extract sand. We have already seen some images of that extraction process in an earlier post[6]. The area immediately North of La Foux was an extensive sand quarry and extracted sand was delivered to La Foux station by a private railway. The layout of that railway can be seen on the image below. A picture which includes the locomotive and wagons involved can be seen in a previous post[6]. The area shown in the aerial photograph below includes what is today a large marina, a park and an exclusive residential area. The area immediately north of the station was the Racecourse. The photo below the aerial image is taken from this area looking back at the station.

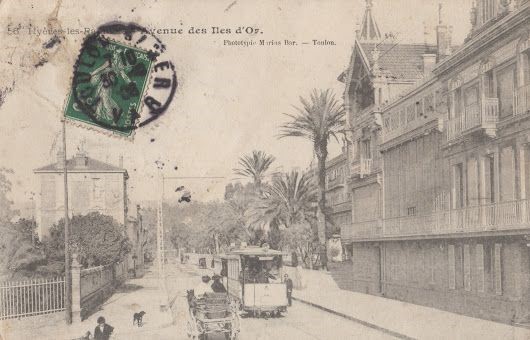

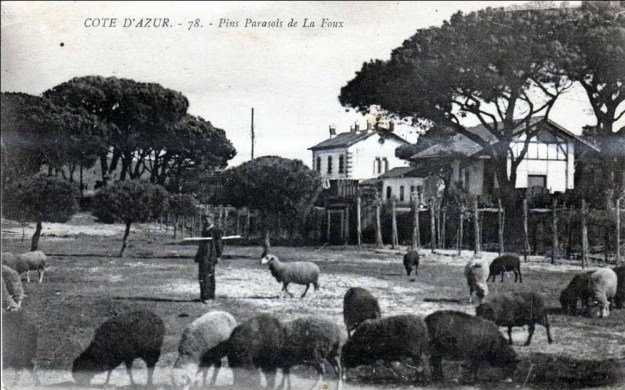

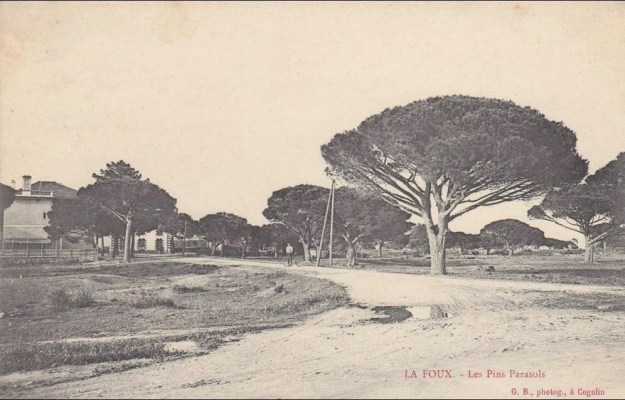

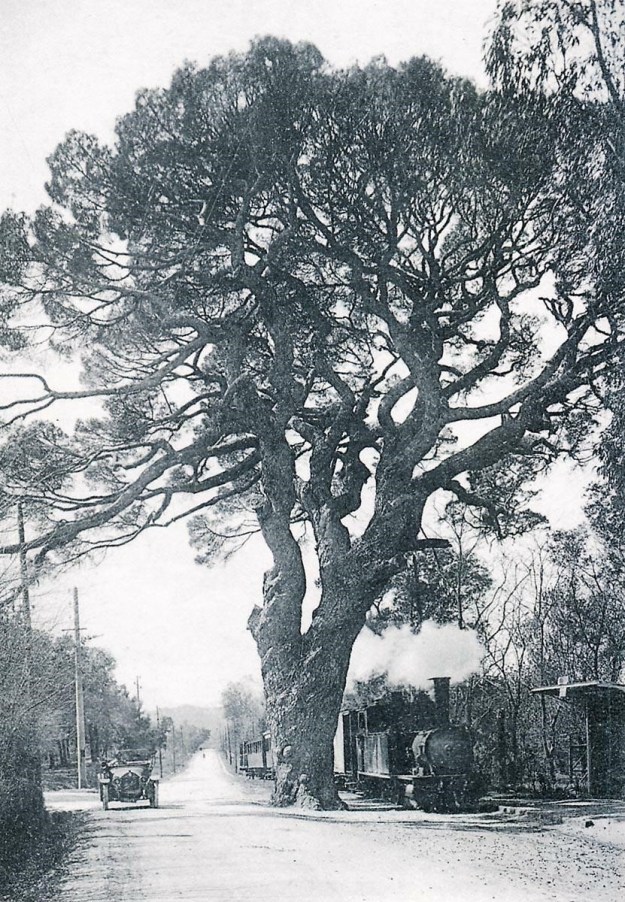

The station is surrounded by pine trees as the following images show.

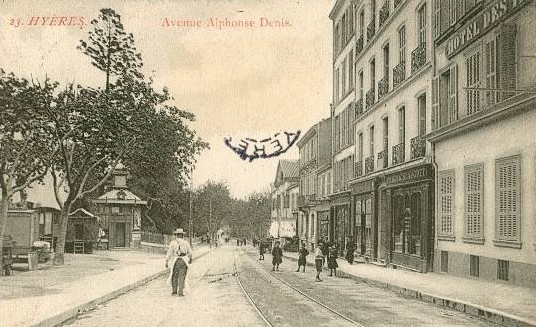

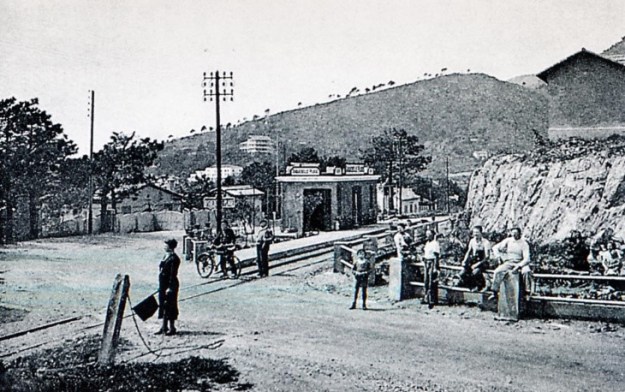

La Foux station knew enormous crowds of travellers in summer, when horse races and bullfights took place on the nearby racecourse. This view is of the avenue leading to the Station (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

La Foux station knew enormous crowds of travellers in summer, when horse races and bullfights took place on the nearby racecourse. This view is of the avenue leading to the Station (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

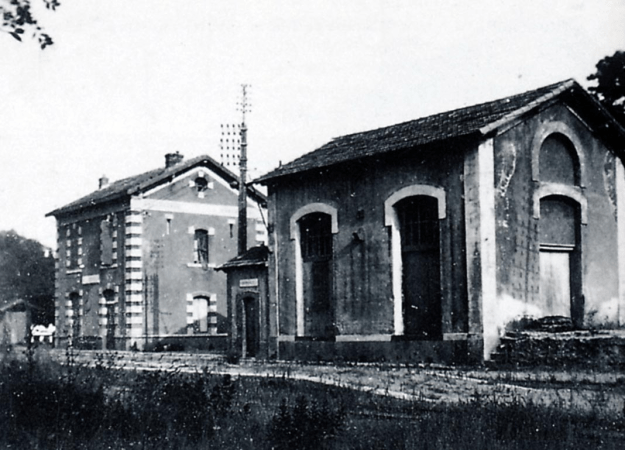

This view shows the courtyard of La Foux station, from left to right, the pumping station which lifts water to the 120 cubic metre water tank, the water tank, the workshop and engine shed (Raymond BERNARDI Collection)

This view shows the courtyard of La Foux station, from left to right, the pumping station which lifts water to the 120 cubic metre water tank, the water tank, the workshop and engine shed (Raymond BERNARDI Collection)

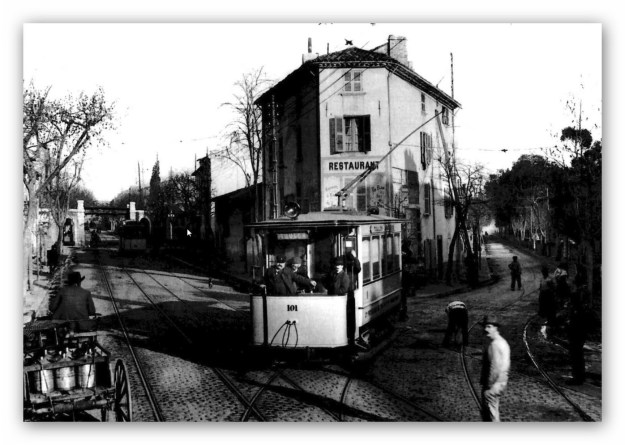

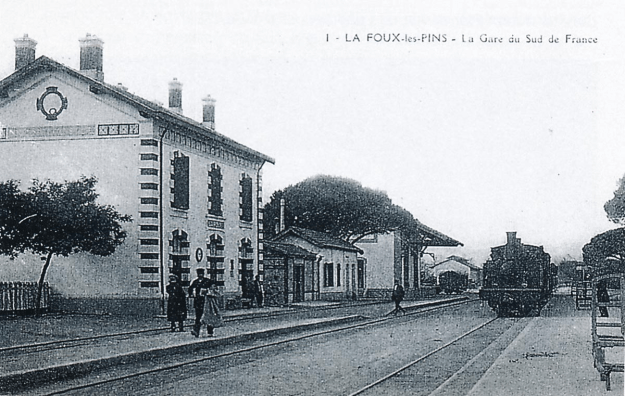

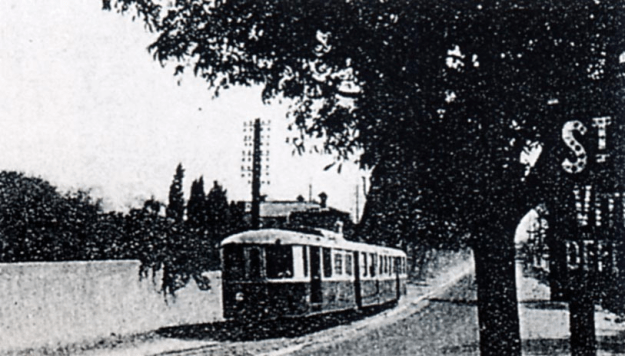

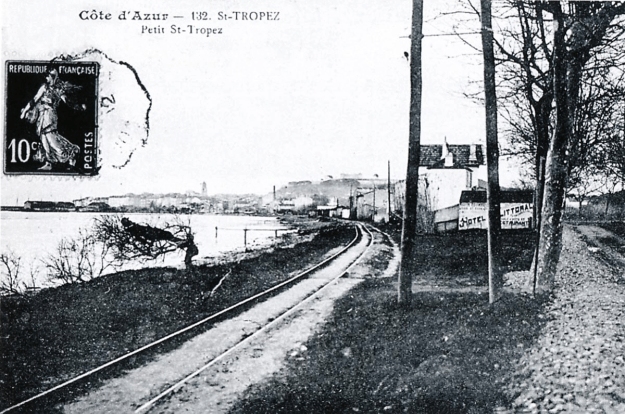

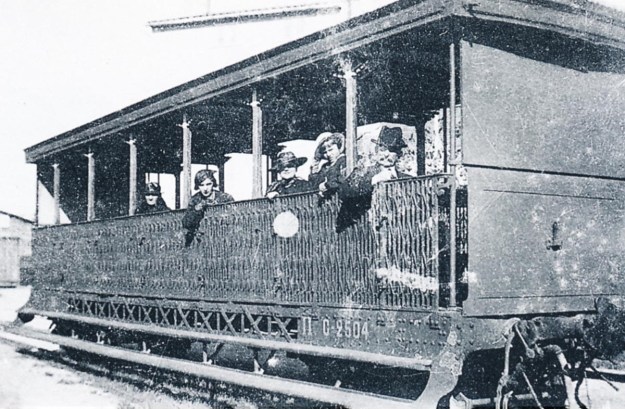

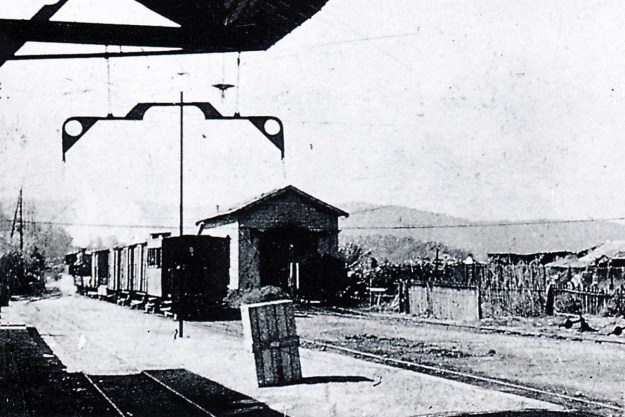

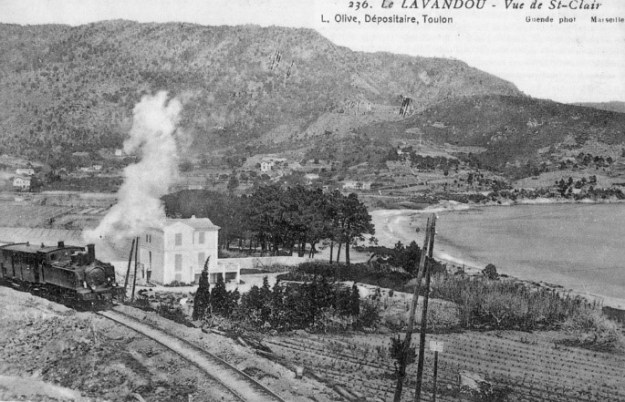

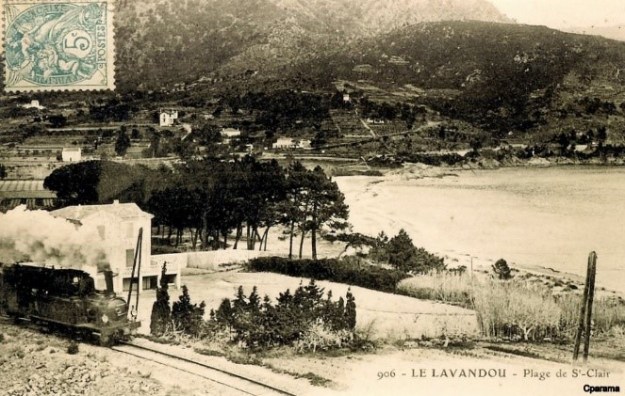

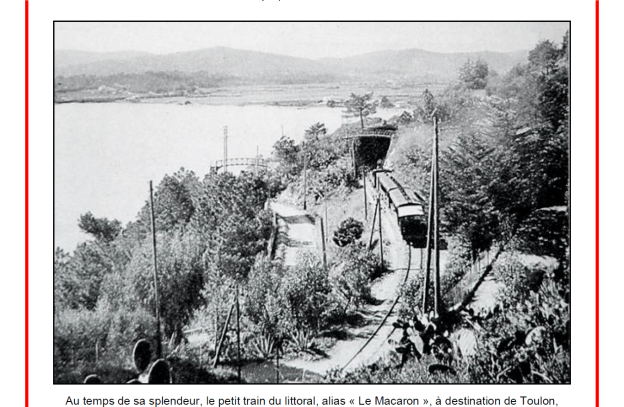

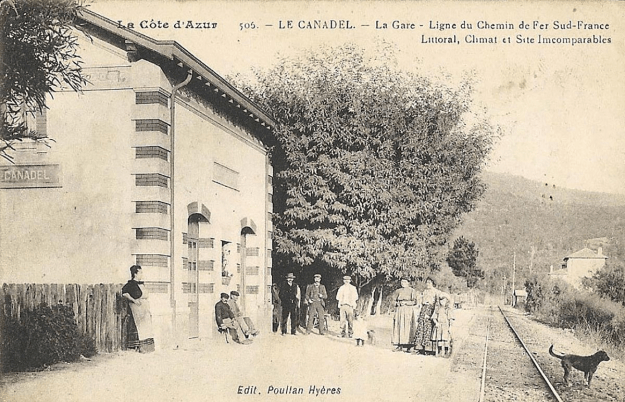

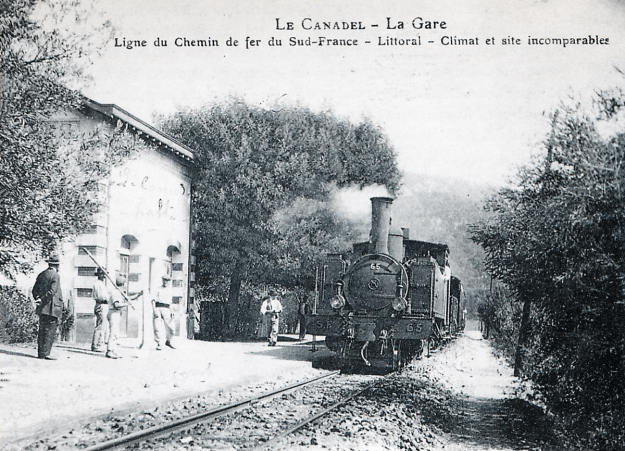

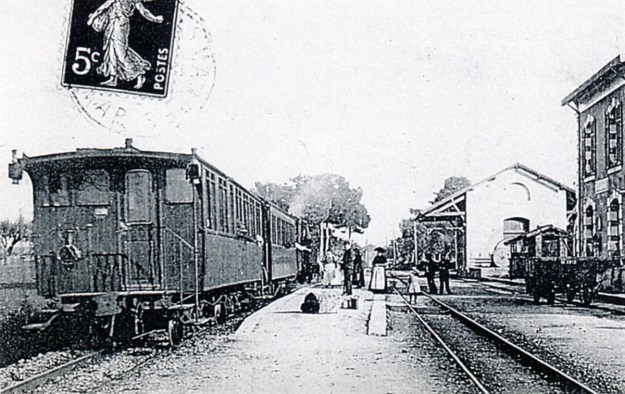

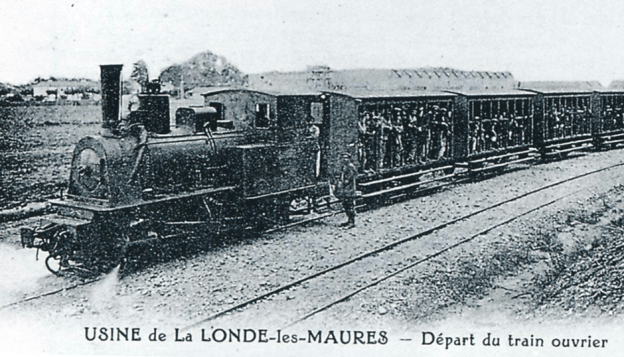

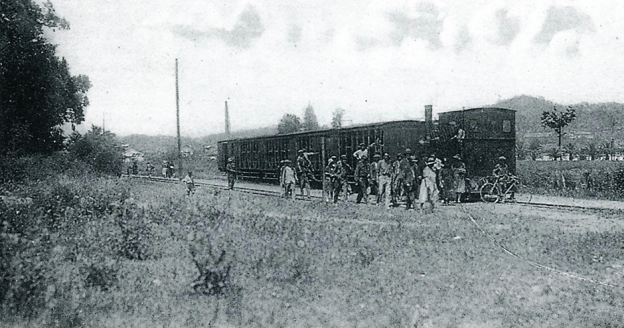

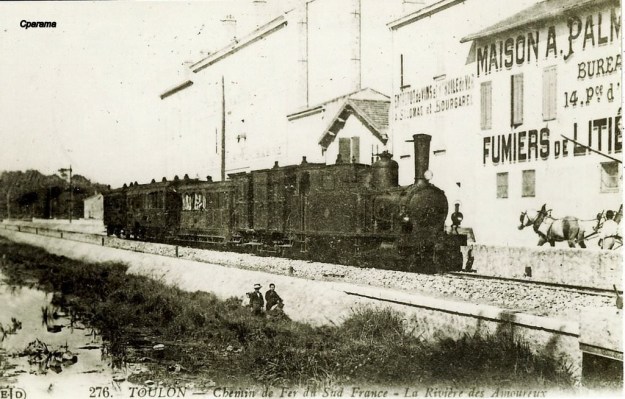

Shortly after its commissioning in 1894, the St.Tropez tramway is seen here. The train is off the Littoral line from Toulon to La Foux station (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

Shortly after its commissioning in 1894, the St.Tropez tramway is seen here. The train is off the Littoral line from Toulon to La Foux station (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

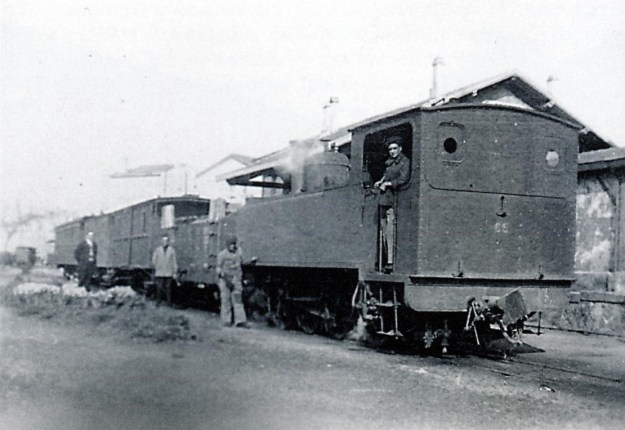

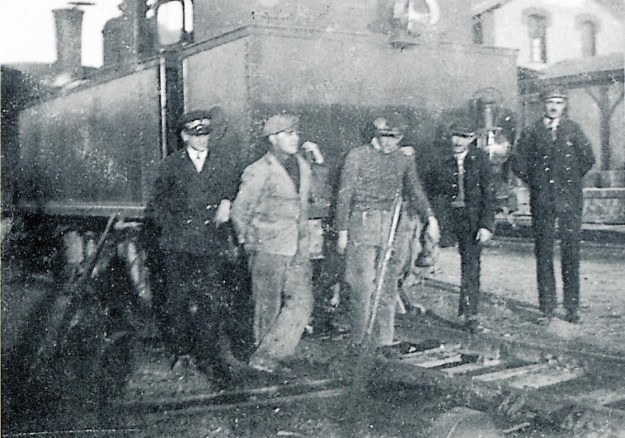

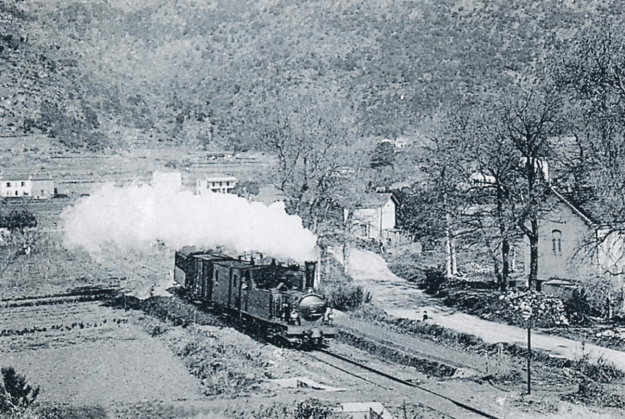

A 0-6-0T Corpet – Louvet 70-72 locomotive pulls two bogie cars usually used on the main line, on the shuttle on the branch/tramway. The increased passenger traffic necessitated this sharing of resources (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

A 0-6-0T Corpet – Louvet 70-72 locomotive pulls two bogie cars usually used on the main line, on the shuttle on the branch/tramway. The increased passenger traffic necessitated this sharing of resources (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

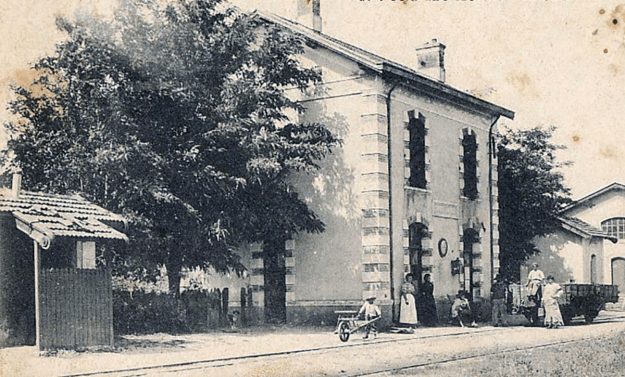

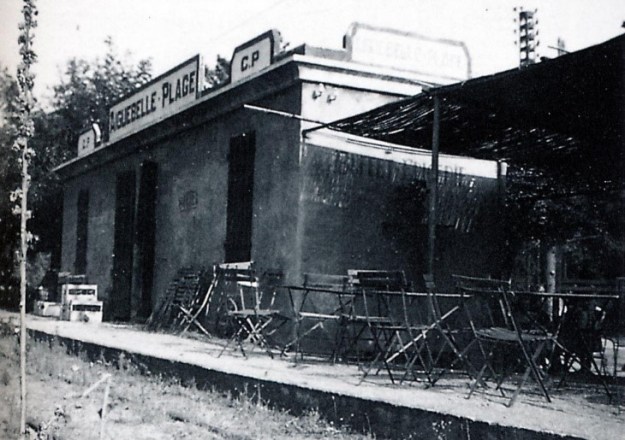

The Station building at La Foux can just be picked out behind the trees in this picture.

The Station building at La Foux can just be picked out behind the trees in this picture.

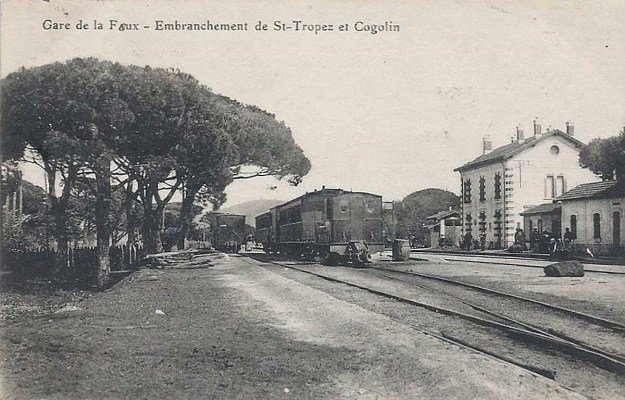

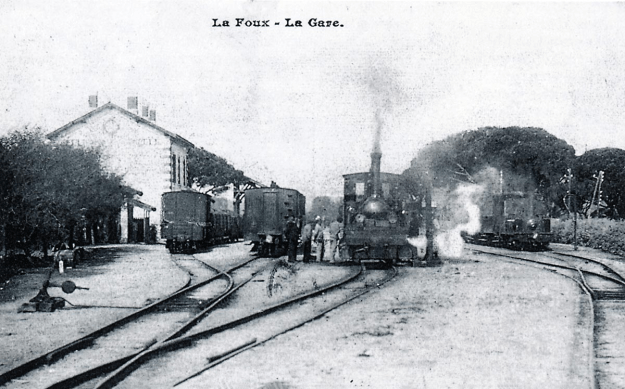

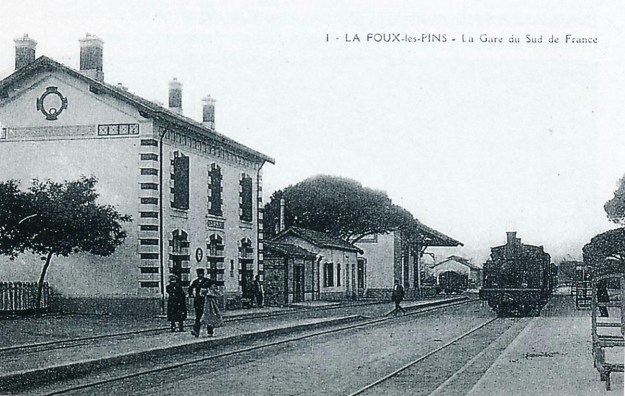

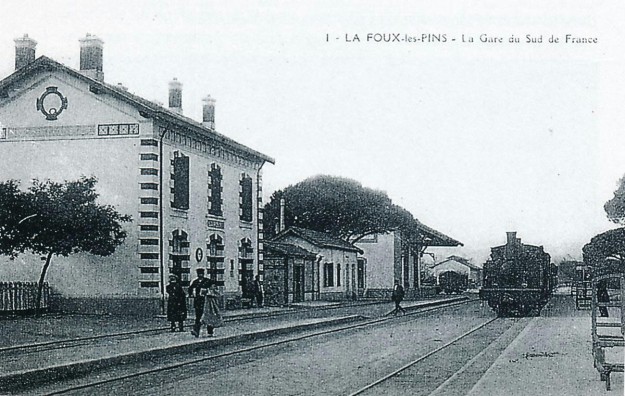

La Foux station at the beginning of the 20th century. From left to right: the pines of the racecourse, the track for St. Tropez, a train for Cogolin with an 0-6-0T Corpet-Louvet series 70 to 72, a train for Hyères and a long mixed train for St.Raphaël behind a 2-6-0T Pinguely series 41 to 44 (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

La Foux station at the beginning of the 20th century. From left to right: the pines of the racecourse, the track for St. Tropez, a train for Cogolin with an 0-6-0T Corpet-Louvet series 70 to 72, a train for Hyères and a long mixed train for St.Raphaël behind a 2-6-0T Pinguely series 41 to 44 (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

In this view of La Foux station before 1910, the locomotive refueling on the central lane seems to be the 0-6-0T Krauss Weidknecht No. 78 “La Madeleine”, perhaps used to pull trains of sand to and from the area we now know as Port Grimaud. On the right is a 0-6-0T Corpet-Louvet series 70 to 72 at the head of a Cogolin to St. Tropez train (André JACQUOT Collection)

In this view of La Foux station before 1910, the locomotive refueling on the central lane seems to be the 0-6-0T Krauss Weidknecht No. 78 “La Madeleine”, perhaps used to pull trains of sand to and from the area we now know as Port Grimaud. On the right is a 0-6-0T Corpet-Louvet series 70 to 72 at the head of a Cogolin to St. Tropez train (André JACQUOT Collection)

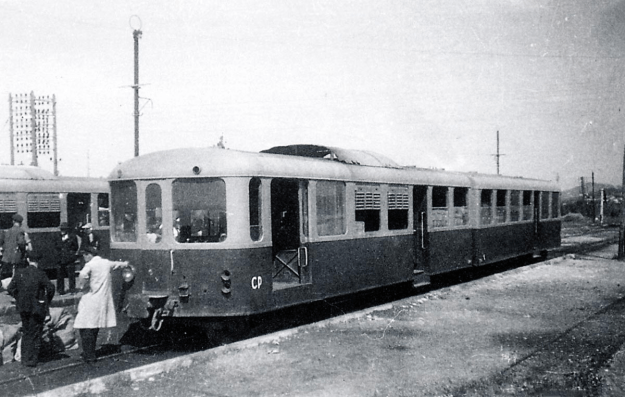

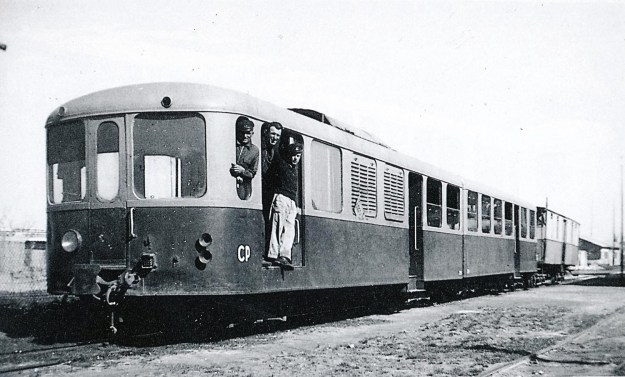

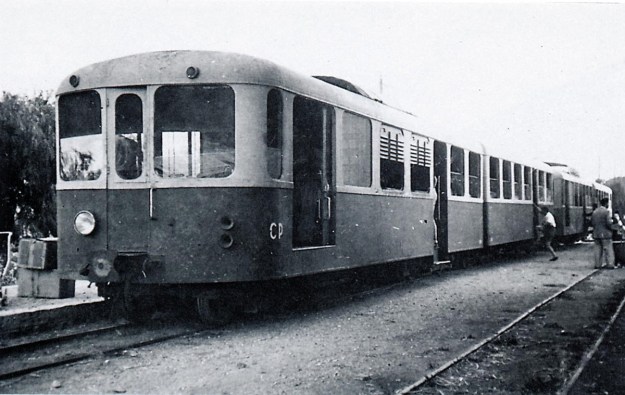

The driver of a Brissonneau & Lotz railcar waiting for passengers to re-embark at La Foux station (Photo Jacques CHAPUIS – FACS-UNECTO collection).

The driver of a Brissonneau & Lotz railcar waiting for passengers to re-embark at La Foux station (Photo Jacques CHAPUIS – FACS-UNECTO collection).

Two railcars cross at La Foux Station on 25th May 1948, shortly before the closure of the line.

Two railcars cross at La Foux Station on 25th May 1948, shortly before the closure of the line.

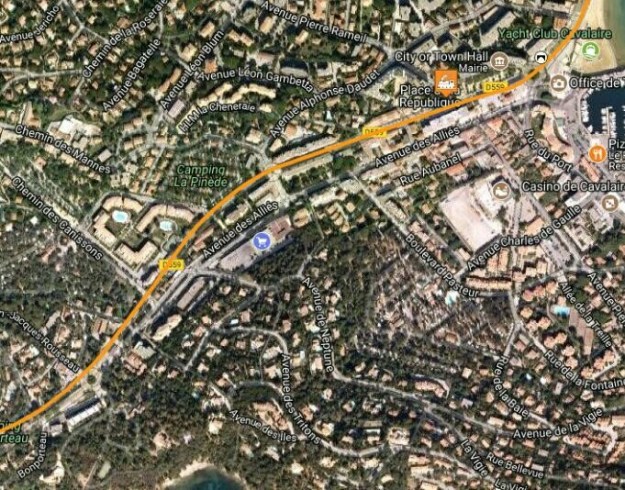

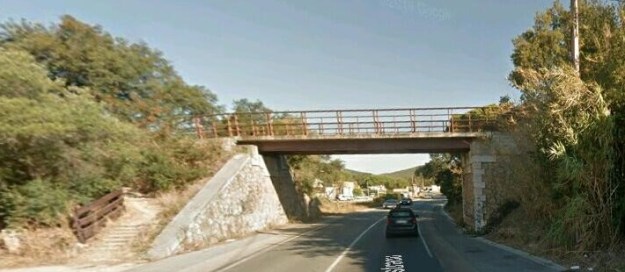

Leaving La Foux Station the line to St. Raphael parted from the line to Cogolin and tuned to the North-west, running alongside the main road. The land to the North of the line was open fields. It is now an area known as Port Cogolin. The area is outlined in blue on the satellite image below.

Leaving La Foux Station the line to St. Raphael parted from the line to Cogolin and tuned to the North-west, running alongside the main road. The land to the North of the line was open fields. It is now an area known as Port Cogolin. The area is outlined in blue on the satellite image below.

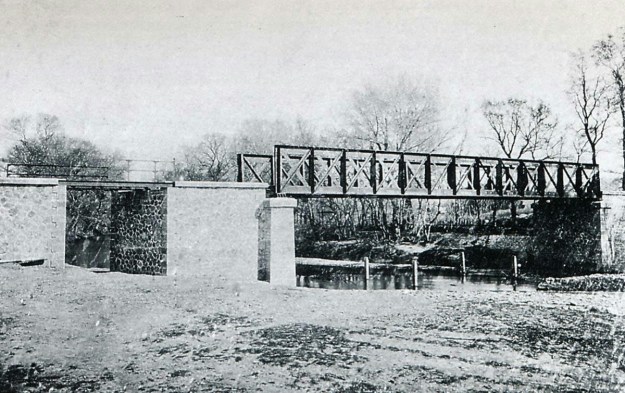

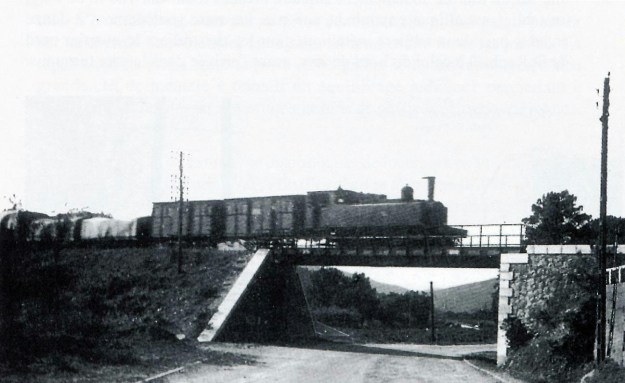

Immediately beyond what is now Port Cogolin the railway crossed the River Giscle on what appears to have been a metal truss girder bridge. The pictures below show the present-day bridges. There is a cycleway on the line of the old railway and the old road bridges have been replaced by a more up-to-date concrete structure. I have provided a picture from elsewhere of what the bridge probably looked like immediately after closure of the line in the late 1940s as well as an aerial photograph at the highest possible resolution of the road and rail bridges at that time.

Once across the river, the road and rail routes remained close to each other, sheltered by a single row of trees in the margin of the road.

The River Giscle continues to be prone to flooding. Significant flooding meant that the causeway of the road and railway needed to be broken at regular intervals by bridges that would release the peak flood flows. A series of bridges followed the main river bridge. Pont de décharge n°1 de la Gisle was the first of these and was at a position very close to the entrance road to the modern Port Grimaud.

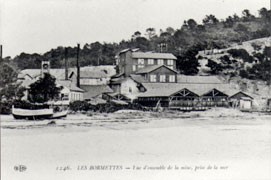

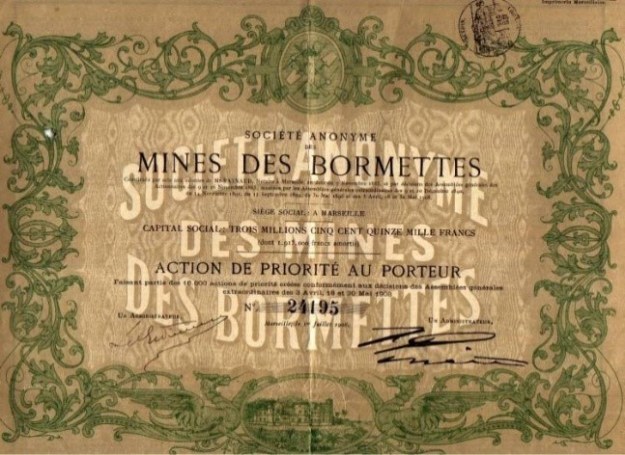

At approximately this location a second track[c.f., 6] of about 850 metres in length headed towards the sea to basins where steam dredgers excavated estuarial sand.

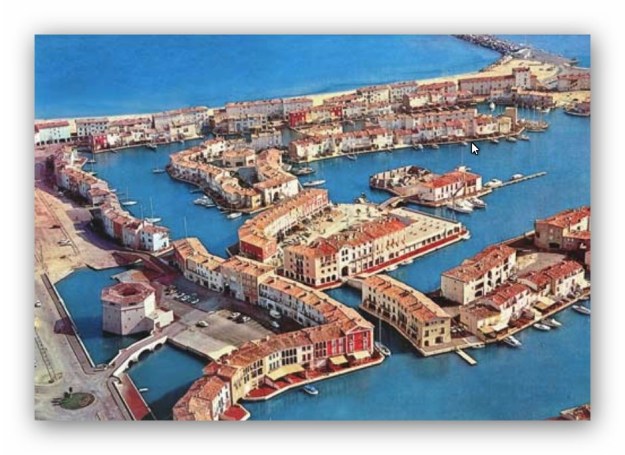

The area is now vastly different. Port Grimaud, as it is now, was the vision of one man. Francois Spoerry had a vision of what the seemingly unusable land at the end of the Golfe de St. Tropez could be used for.

The area is now vastly different. Port Grimaud, as it is now, was the vision of one man. Francois Spoerry had a vision of what the seemingly unusable land at the end of the Golfe de St. Tropez could be used for.

In 1962, Spoerry bought the land at a very cheap price because it was of no interest to developers. It was a swampy area infested with mosquitoes and invaded by reed beds, tall grasses and bushes, among which were a few stoney paths[7].

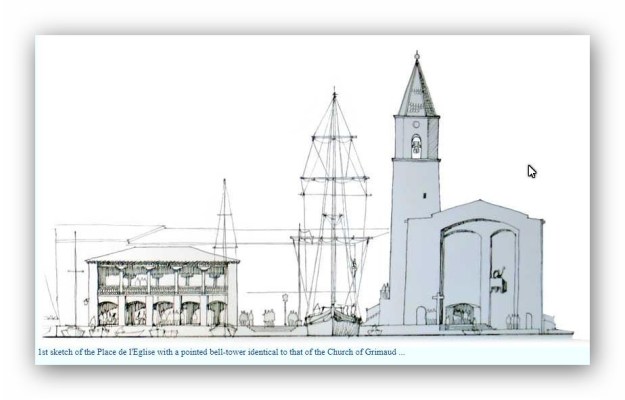

The village and canals were developed over a period of around 10 years. Images from that period follow below. The first is one of the drawings of the site produced by Spoerry, there is then a sequence of images from different years, showing the development of the site.

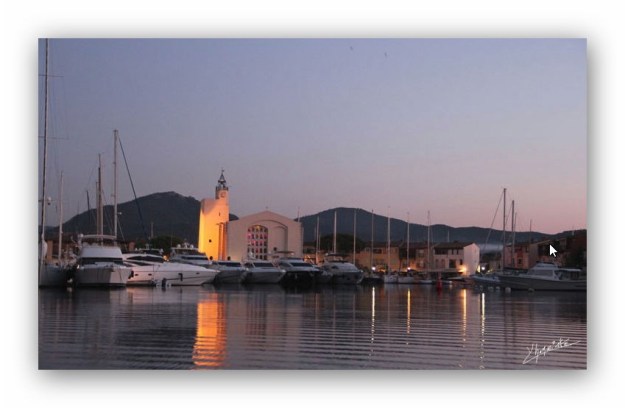

The image immediately above was taken in 1970. The images below show a little of the construction of the church built on site.

The image immediately above was taken in 1970. The images below show a little of the construction of the church built on site.

The church design was adjusted before building and no longer reflected directly the design of the church in Grimaud Village.

The church design was adjusted before building and no longer reflected directly the design of the church in Grimaud Village.

Port Grimaud has become one of the places to live on the Cote d’Azur, in the middle of the 20th Century it was a sand quarry! Spoerry explained his vision to a journalist from ‘Alsace’: “Port Grimaud was born from my desire to have a small house at the water’s edge with a boat in front of my door. … But I also planned to create a village and not just a collection of houses, a real village with a heart, … a church, hotels and restaurants. … A village as it would have been if architects had not existed. …” [8].

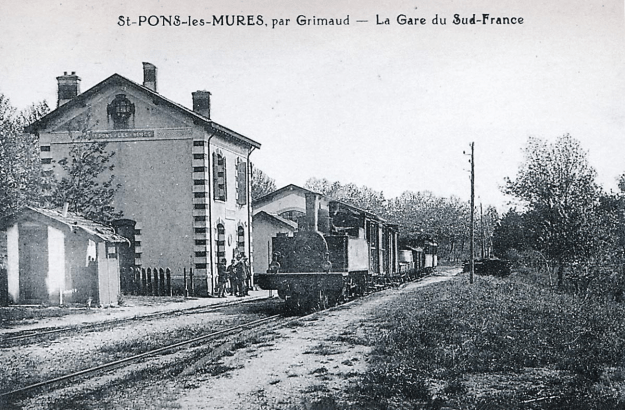

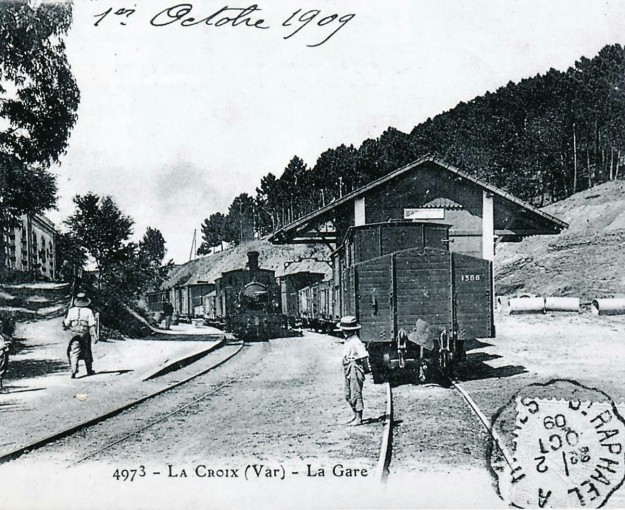

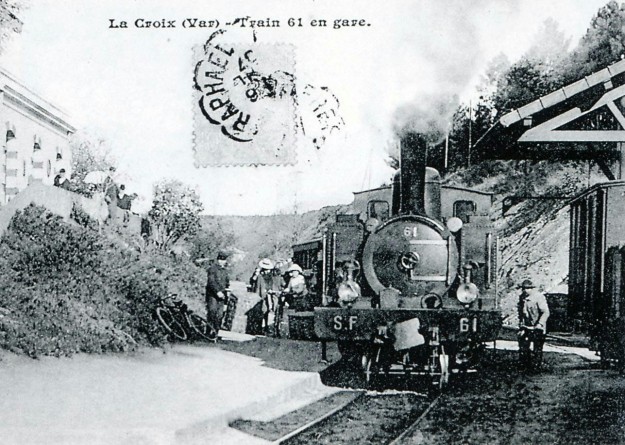

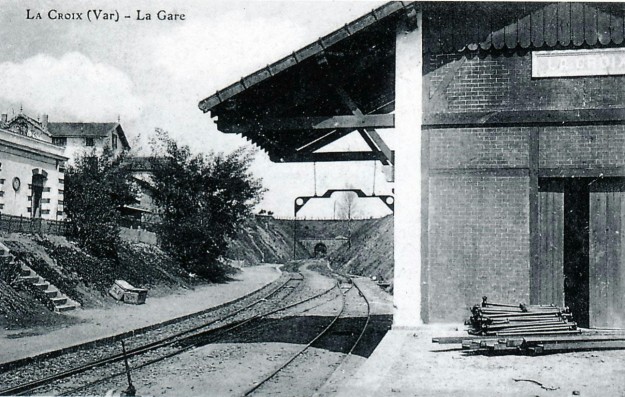

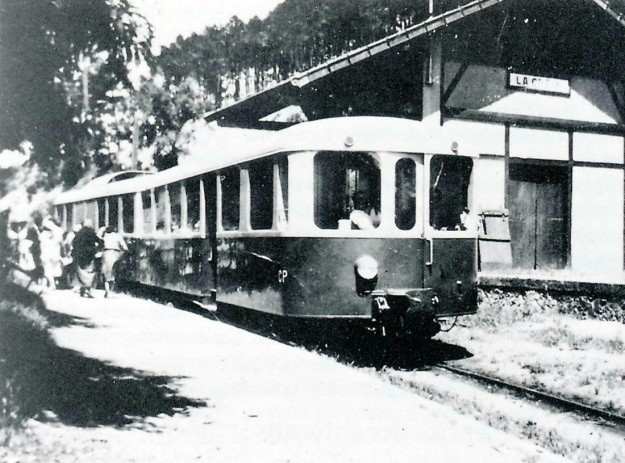

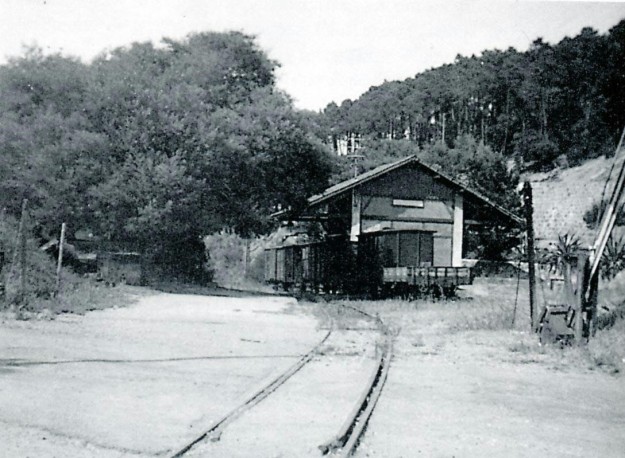

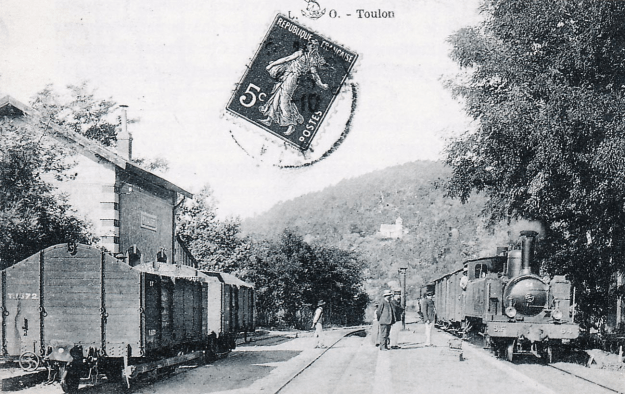

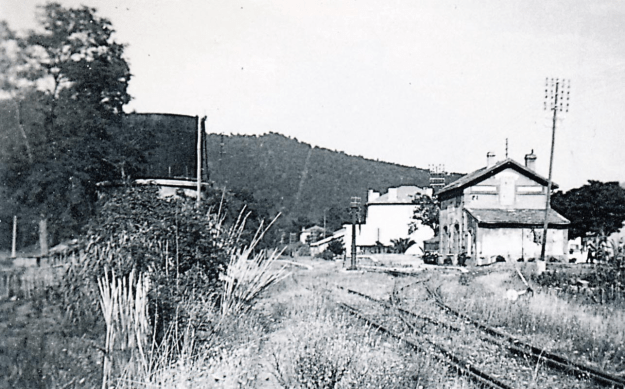

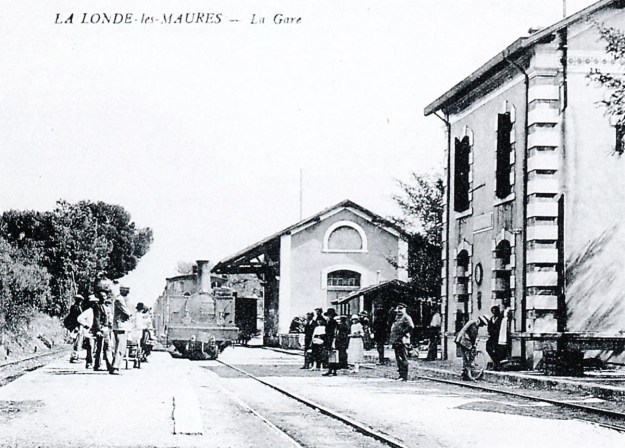

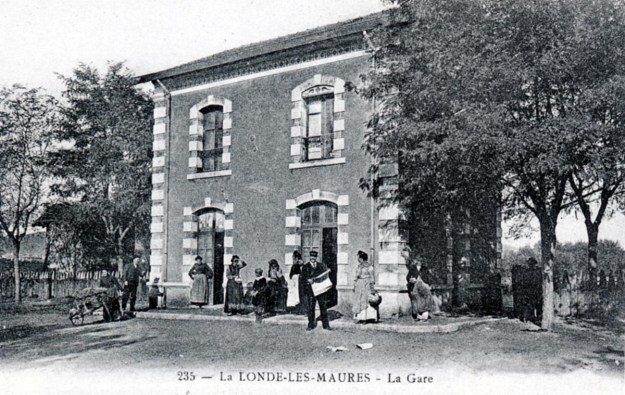

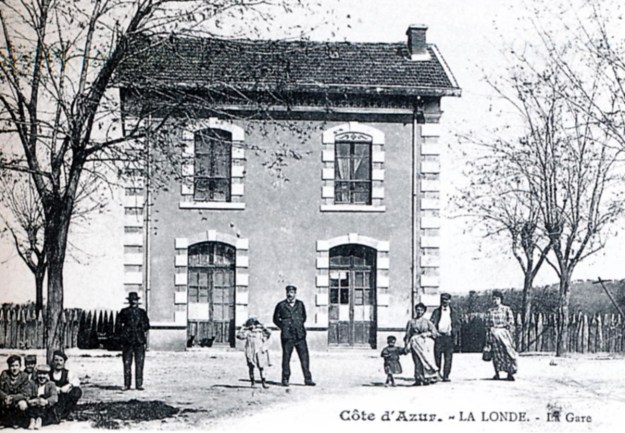

We move on along th e line towards St. Raphael and we encounter two more flood relief bridges, Pont de décharge n°2 de la Gisle, and predictably, Pont de décharge n°3 de la Gisle, before reaching the next station, Saint Pons-les-Mûres (Grimaud until 1904). The Station was a 3rd Class establishment. The picture below is from the Collection of Raymond BERNARDI.

The photo above is of a mixed train from St. Raphael to Toulon pulled by a 4-6-0T Pinguely series 41 to 44, in St.Pons-les-Mûres around 1920 (Collection Raymond BERNARDI).

The station has disappeared and has been replaced by a carpark and restaurant.

The station has disappeared and has been replaced by a carpark and restaurant.

The station was on a curve in the direction of the line. After leaving the station the line travelled straight once more, separated from the road by a line of trees. It soon crossed Pont du Vallat des Mûres and continued in an East-Northeast direction. Its formation is covered by a cycleway. The tress which separate the road from the old railway are now Plane trees, historically they may well have been pines as nearer La Foux. The cycleway can be seen behind the bus-stop in the next image which is taken just beyond the access to the station (now restaurant and car-park).

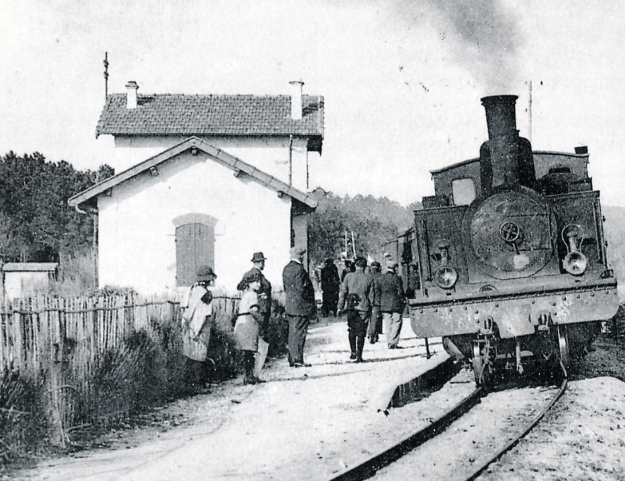

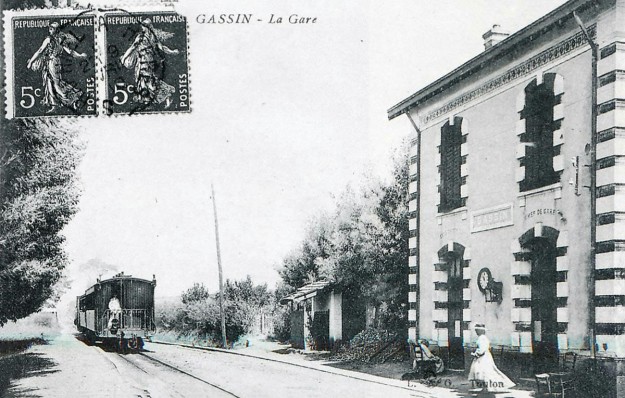

The line crossed another bridge, Pont du ruisseau des Mûres and followed the coastline to the next small halt – Guerrevieille-Beauvallon (Guerrevieille until 1913). The photograph shows a 2-6-0T PInguely Series 41-44 locomotive stopped at the halt. The line continued to follow the D559 and to hug the coast-line to the next stop at La Croisette.

The line continued to follow the D559 and to hug the coast-line to the next stop at La Croisette.

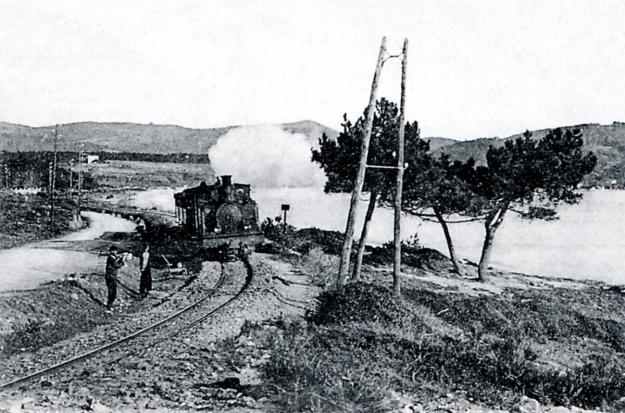

The picture above is taken on the line between Guerrevieille-Beauvallon and La Croisette and is typical of the line along this length. The train is in the care of a 2-6-0T Pinguely series 41 to 44 and travelling towards La Foux. In this area, the railway was frequently subject to the onslaught of the sea during windstorms from the east. Although intended for the length of the line betweem Toulon and Hyères, the 2-6-0T Pinguely series 41 to 44 locomotives were often seen on the Eastern end of the line close to St. Raphael (Jean-Paul PIGNEDE Collection).

The picture above is taken on the line between Guerrevieille-Beauvallon and La Croisette and is typical of the line along this length. The train is in the care of a 2-6-0T Pinguely series 41 to 44 and travelling towards La Foux. In this area, the railway was frequently subject to the onslaught of the sea during windstorms from the east. Although intended for the length of the line betweem Toulon and Hyères, the 2-6-0T Pinguely series 41 to 44 locomotives were often seen on the Eastern end of the line close to St. Raphael (Jean-Paul PIGNEDE Collection).

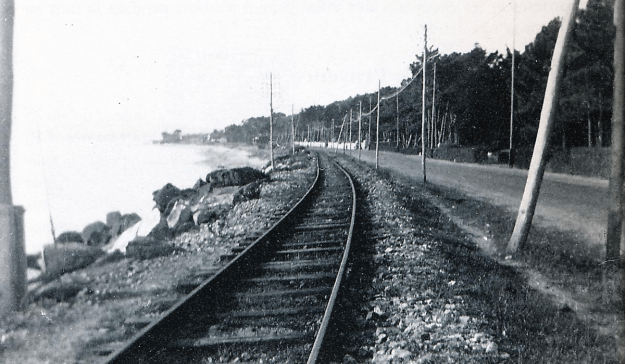

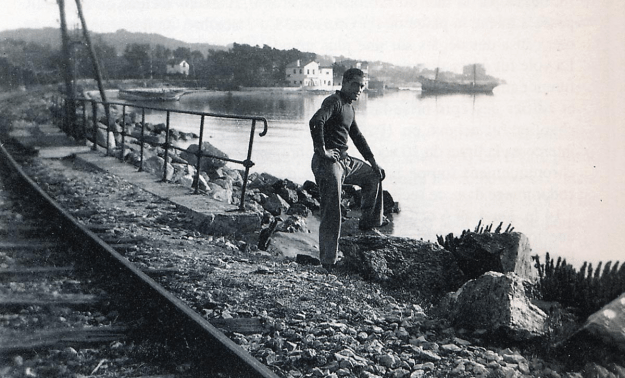

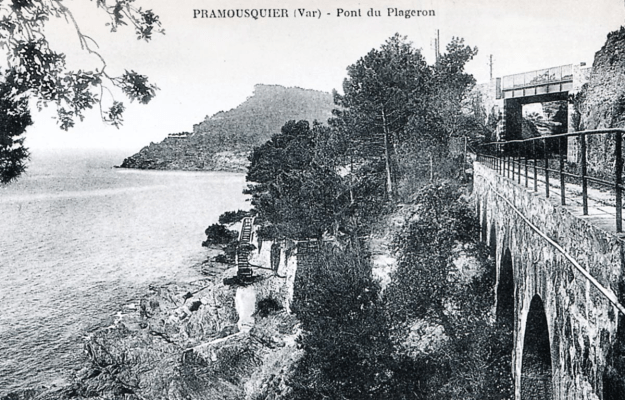

These two images show the proximity of the line to the water’s edge and give an idea too of the boulder protection installed by the railway company to protect their line for the ravages of the sea.

These two images show the proximity of the line to the water’s edge and give an idea too of the boulder protection installed by the railway company to protect their line for the ravages of the sea.

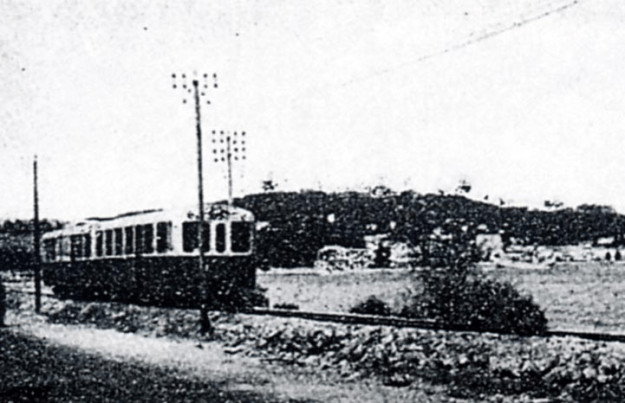

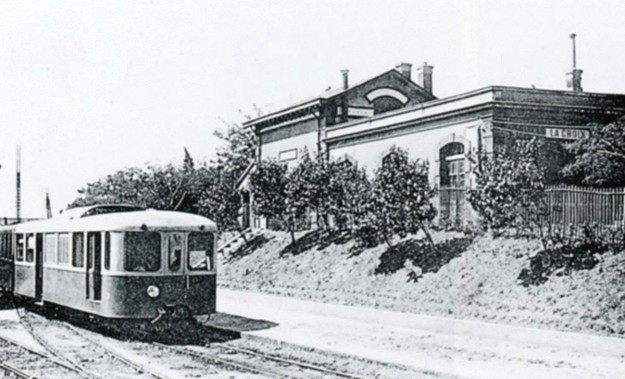

A railcar from St. Maxime close to La Croisette.

A railcar from St. Maxime close to La Croisette.

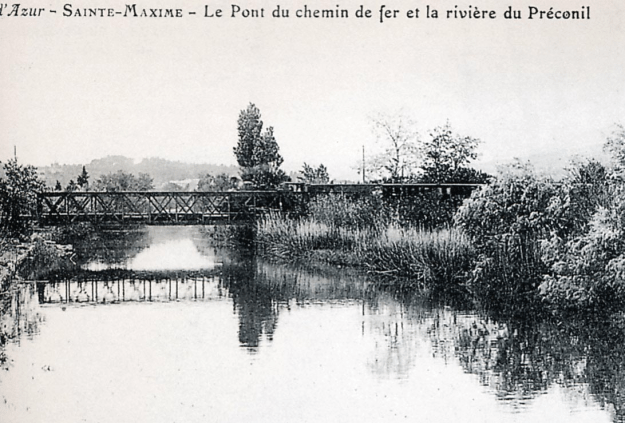

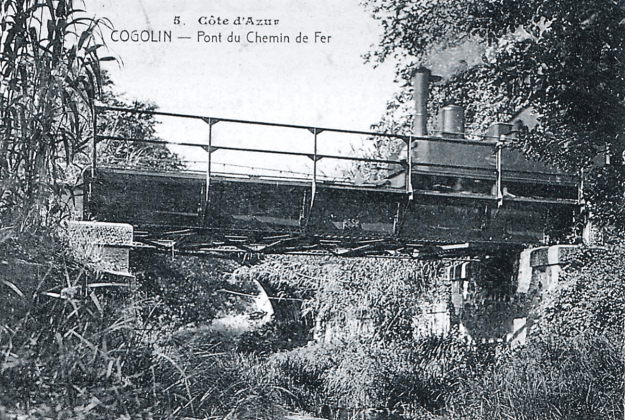

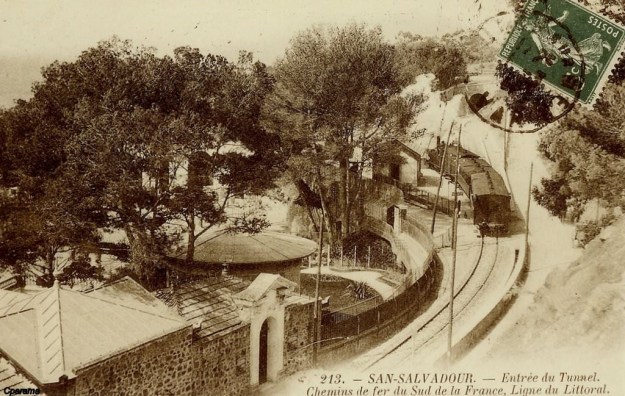

The next major structure on the line was the bridge over the River Préconil. When first constructed the Pont du Préconil was a steel truss girder bridge. The metal bridge built by Gustave Eiffel over the Preconil west of Ste. Maxime (Jean-Paul PIGNEDE Collection)

The metal bridge built by Gustave Eiffel over the Preconil west of Ste. Maxime (Jean-Paul PIGNEDE Collection)

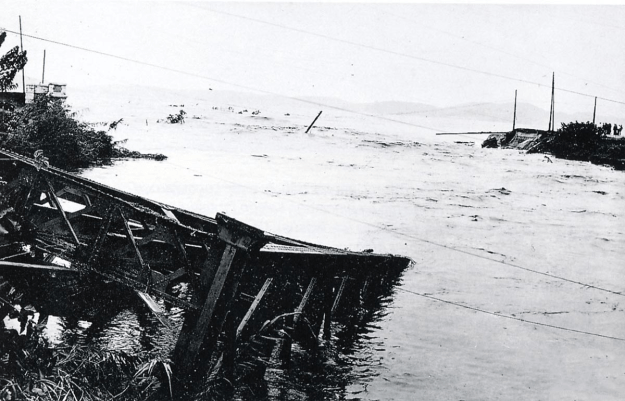

Damage caused by the tidal wave of September 28th and 29th, 1932 at Ste. Maxim. The railway bridge (in the foreground) and the road bridge (beyond) were washed away by the River Préconil (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

Damage caused by the tidal wave of September 28th and 29th, 1932 at Ste. Maxim. The railway bridge (in the foreground) and the road bridge (beyond) were washed away by the River Préconil (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

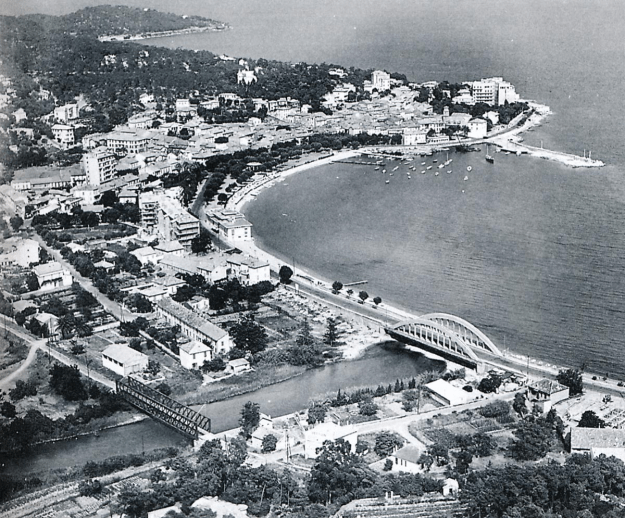

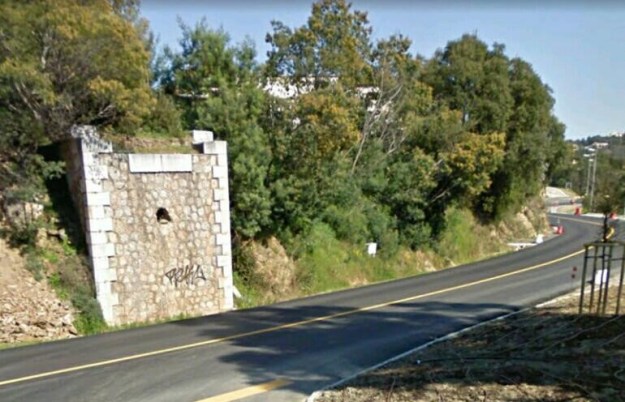

The image above is an aerial view of the western approaches to Sainte-Maxime shortly after the last world war. The Preconil River is in the foreground with the steel railway bridge and the concrete road bridge of the D98. These two structures were rebuilt and widened in 1933, after having been carried away by the flood of 28th September 1932 (Raymond BERNARDI Collection). Google Streetview shows the same location in the picture below.

The image above is an aerial view of the western approaches to Sainte-Maxime shortly after the last world war. The Preconil River is in the foreground with the steel railway bridge and the concrete road bridge of the D98. These two structures were rebuilt and widened in 1933, after having been carried away by the flood of 28th September 1932 (Raymond BERNARDI Collection). Google Streetview shows the same location in the picture below.

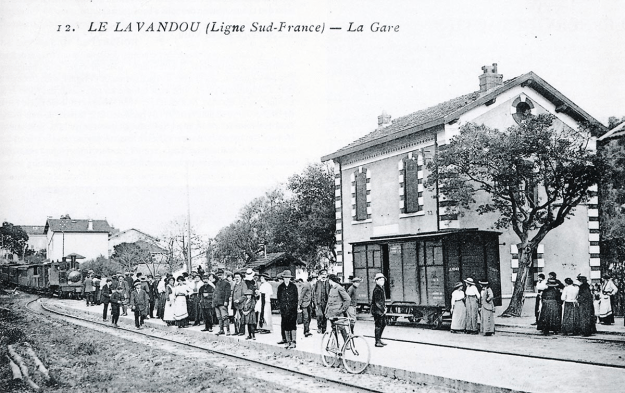

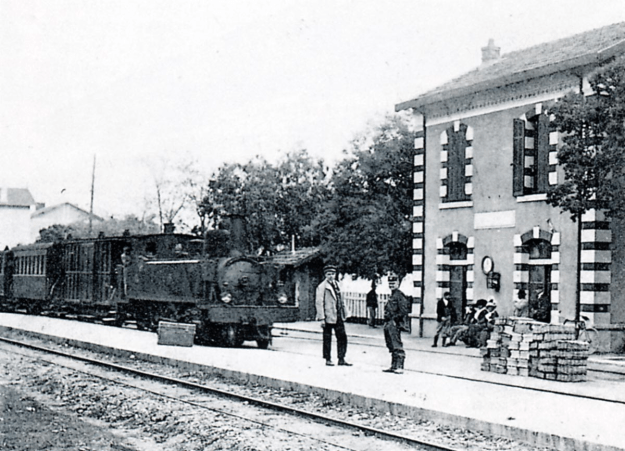

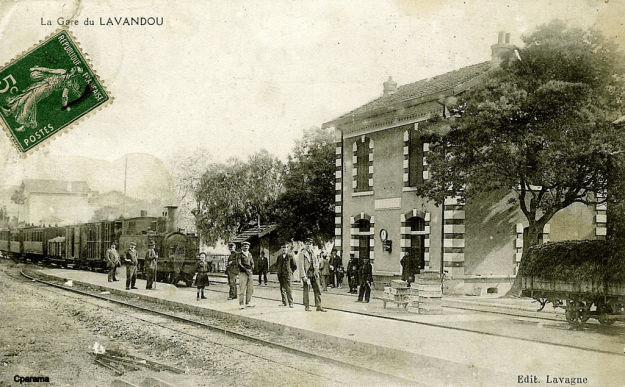

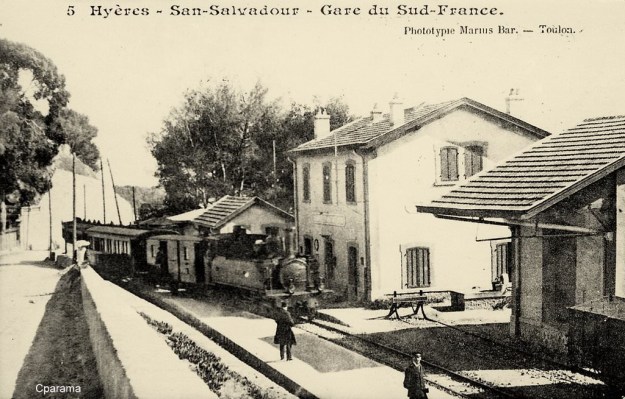

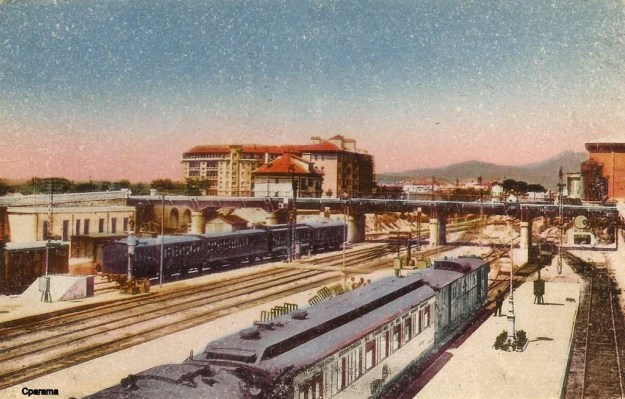

After crossing the river, the railway left the coast behind and travelled into the middle of Sainte-Maxime. We alight from our train at the Station and temporarily end our journey here.

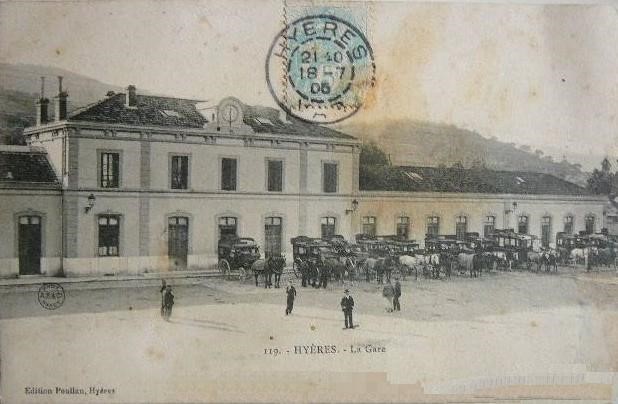

The train in the picture is pulled by a 2-6-0T Pinguely series 41 to 44. The photo is taken on the eve of the First World War and the station is very busy (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

The train in the picture is pulled by a 2-6-0T Pinguely series 41 to 44. The photo is taken on the eve of the First World War and the station is very busy (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

References

[1] Roland Le Corff; http://www.mes-annees-50.fr/Le_Macaron.htm, accessed 13th December 2017.

[2] Marc Andre Dubout; http://marc-andre-dubout.org/cf/baguenaude/toulon-st-raphael/toulon-st-raphael1.htm, accessed 14th December 2017

[3] Jean-Pierre Moreau; http://moreau.fr.free.fr/mescartes/ToulonGareSudFrance.html, accessed 24th December 2017.

[4] José Banaudo; Histoire des Chemins de Fer de Provence – 2: Le Train du Littoral (A History of the Railways of Provence Volume 2: The Costal Railway); Les Éditions du Cabri, 1999.

[5] Roger Farnworth; Ligne du Littoral (Toulon to St. Raphael) – Part 10 – La Foux les Pins to Saint-Tropez (Chemin de Fer de Provence 45); https://rogerfarnworth.wordpress.com/2018/01/08/ligne-du-littoral-toulon-to-st-raphael-part-10-la-foux-les-pins-to-saint-tropez-chemin-de-fer-de-provence-45.

[6] Roger Farnworth; Ligne du Littoral (Toulon to St. Raphael) – Part 11 – La Foux les Pins to Cogolin (Chemin de Fer de Provence 46);https://rogerfarnworth.wordpress.com/2018/01/08/ligne-du-littoral-toulon-to-st-raphael-part-11-la-foux-les-pins-to-cogolin-chemin-de-fer-de-provence-46.

[7] http://www.port-grimaud-immobilier.fr, accessed 5th January 2018

[8] http://www.atelier-crabe.com, accessed 6th January 2018

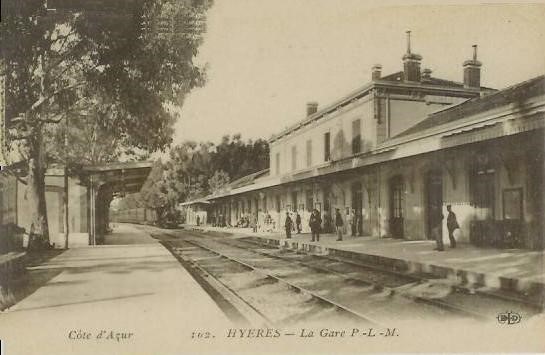

The station was one of the most significant on the line between Saint-Raphael and Toulon and one of the busiest. The line to Saint-Tropez left from the South-east end of the station and ran parallel to the single line to Toulon for a few hundred metres. The two lines separated with the Toulon line turning South and the Saint-Tropez line turning East.

The station was one of the most significant on the line between Saint-Raphael and Toulon and one of the busiest. The line to Saint-Tropez left from the South-east end of the station and ran parallel to the single line to Toulon for a few hundred metres. The two lines separated with the Toulon line turning South and the Saint-Tropez line turning East.

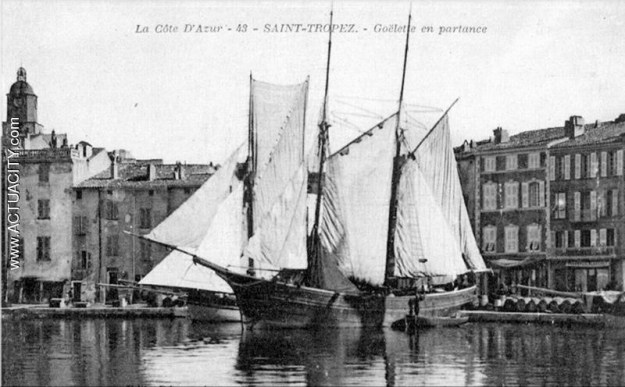

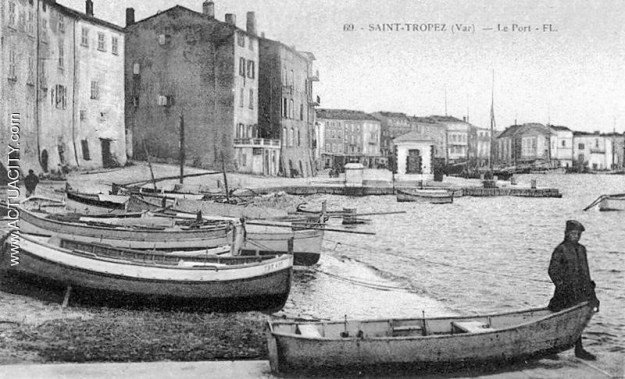

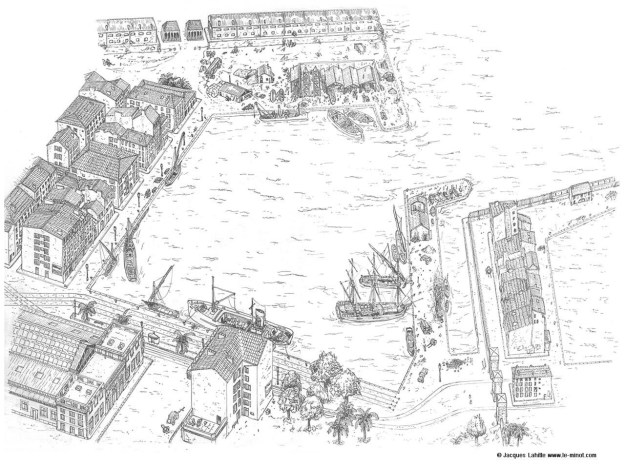

As can be seen in the above image, the original harbour at St. Tropez is much changed and there has been significant land reclamation to enlarge facilities at the port. The aerial photographs below show the port in the time around the closure of the line. Those images are followed by a sequence of photographs culled from the research of Jean-Pierre Moreau [3].

As can be seen in the above image, the original harbour at St. Tropez is much changed and there has been significant land reclamation to enlarge facilities at the port. The aerial photographs below show the port in the time around the closure of the line. Those images are followed by a sequence of photographs culled from the research of Jean-Pierre Moreau [3].

4-6-0T SACM Locomotive No. 62 (Edmund DUCLOS collection).

4-6-0T SACM Locomotive No. 62 (Edmund DUCLOS collection).

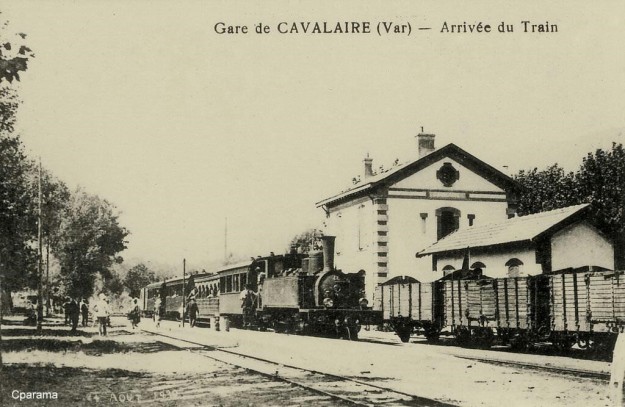

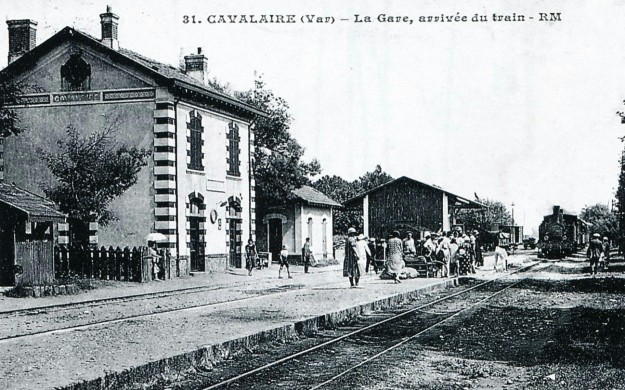

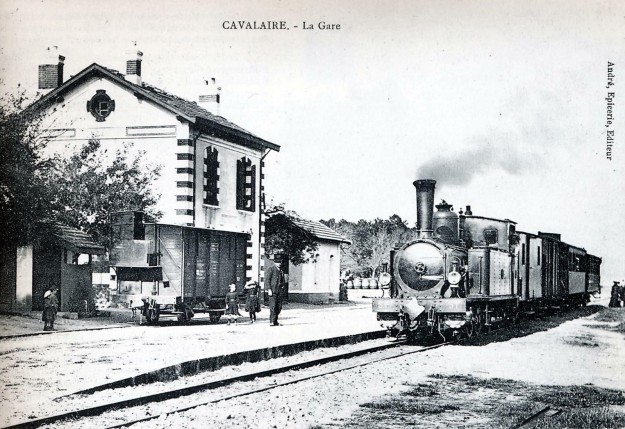

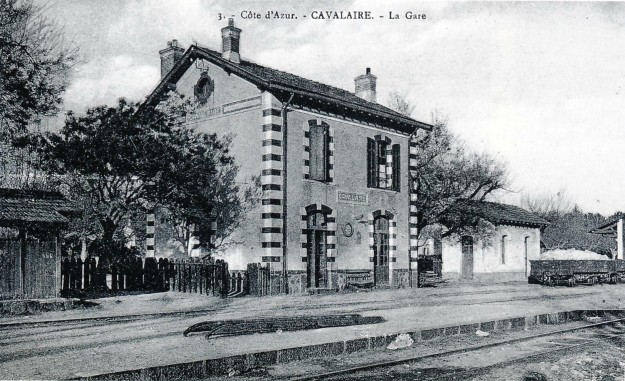

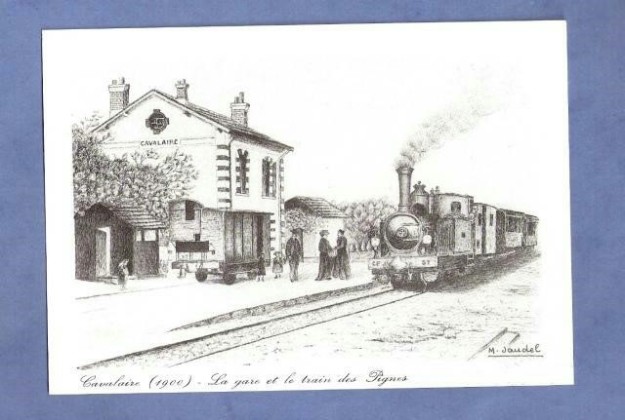

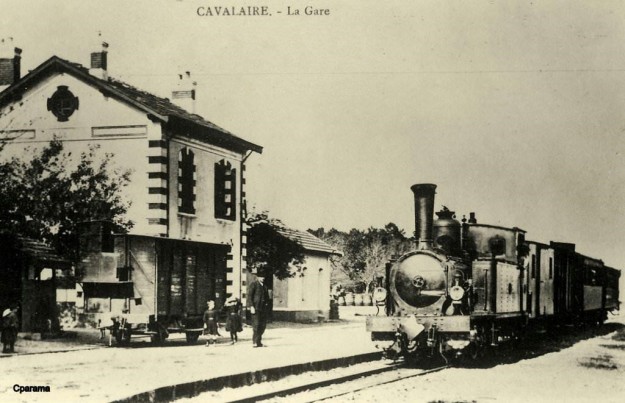

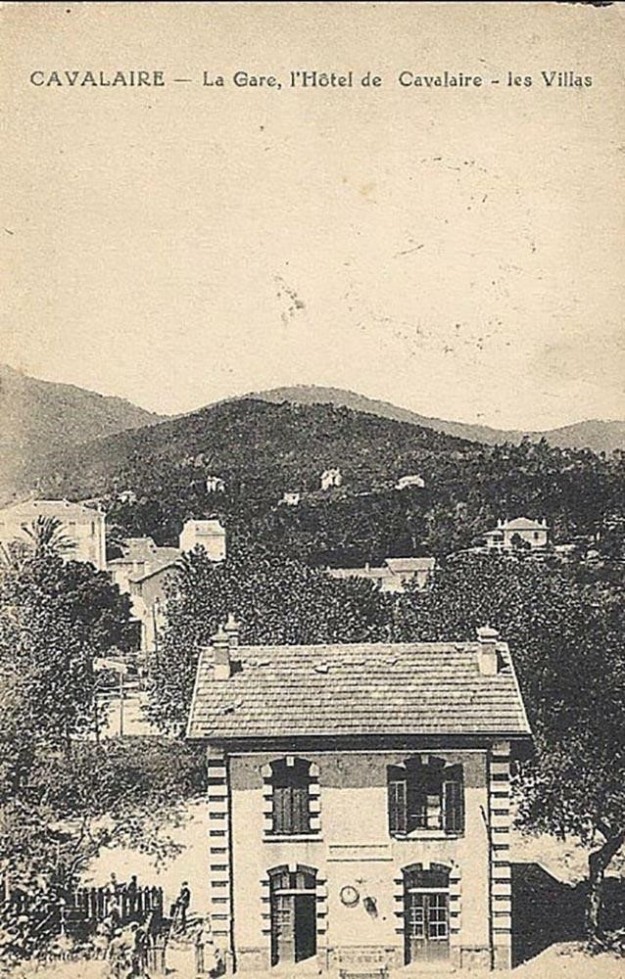

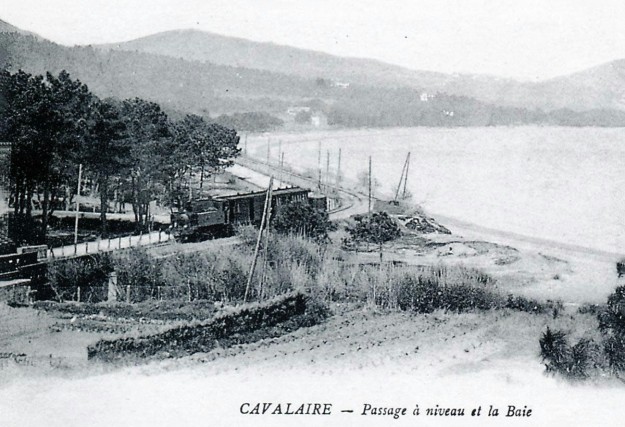

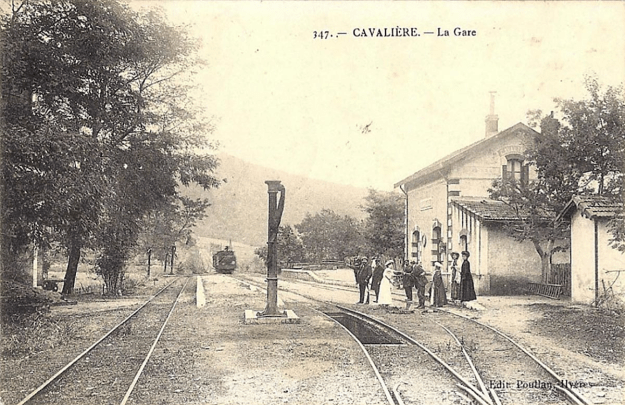

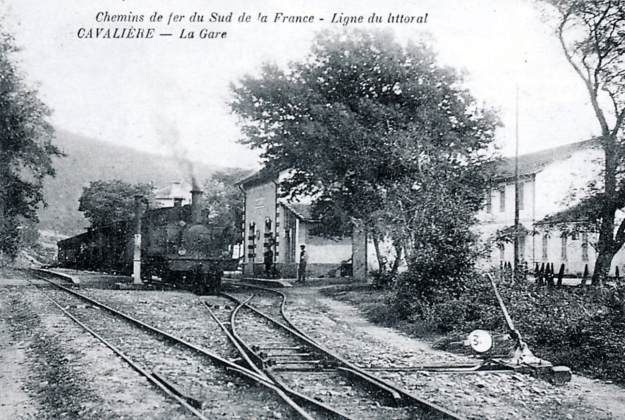

Cavalaire Station sometime between 1925 and 1930. On the platform there is a ladder used to load and unload barrels from van (Jean-Pierre VIGUIE Collection).

Cavalaire Station sometime between 1925 and 1930. On the platform there is a ladder used to load and unload barrels from van (Jean-Pierre VIGUIE Collection). Autorail Brissonnea

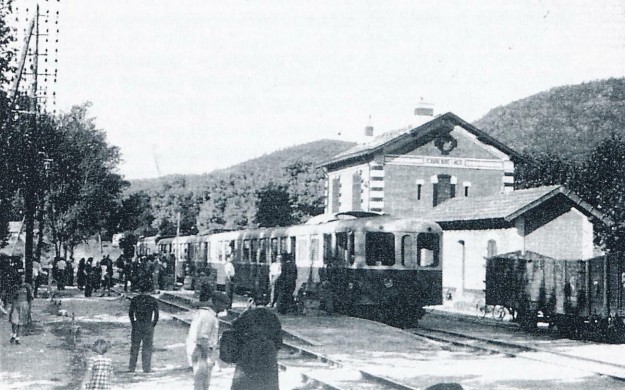

Autorail Brissonnea

By 1978, Cavalaire Sta

By 1978, Cavalaire Sta

The ruins of the castle of the Lords of Fos.

The ruins of the castle of the Lords of Fos.

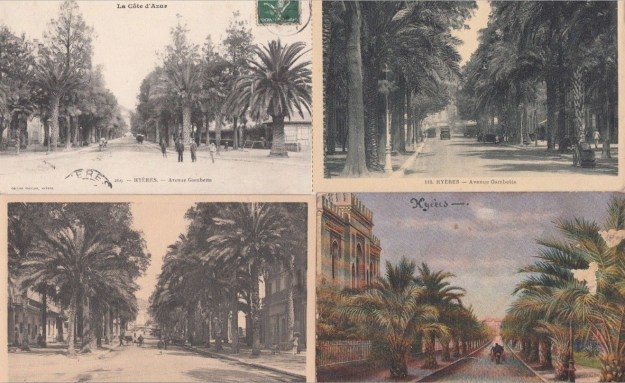

There are squares with fountains, nice shops, art galleries and workshops. We take in the Square of L’Isclou d’Amour, Lou Poulid Cantoun square, square Figuier and des Amoureux square. The old

There are squares with fountains, nice shops, art galleries and workshops. We take in the Square of L’Isclou d’Amour, Lou Poulid Cantoun square, square Figuier and des Amoureux square. The old

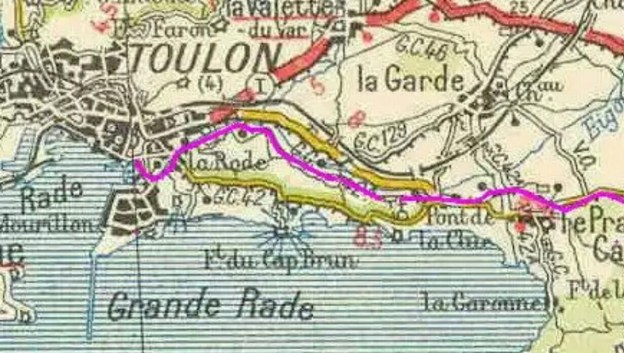

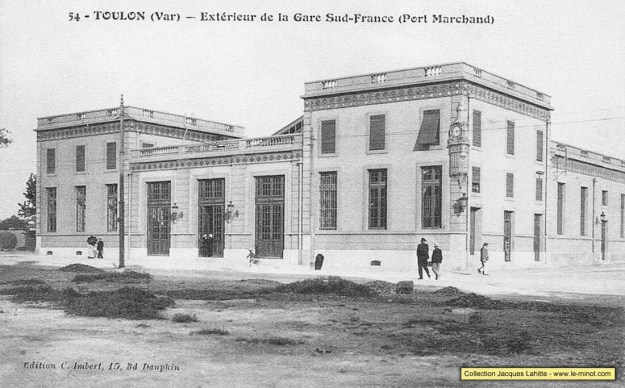

8.7 kilometres from The Gare du Sud in Toulon we arrive at La Pradet Station. It was a more significant stop on the line with passenger facilities, a goods shed, two goods sidings, a passing loop serving two platforms, a 50 cubic-metre water tower and three hydraulic cranes. The Station building still exists, converted into housing it sits close to a cultural centre – “Espace des Arts”, effectively enveloped by it! Little else of the site remains. The first image was taken in 2004 by Jacques Lahitte. The second modern image was taken from Google Streetview in 2017.

8.7 kilometres from The Gare du Sud in Toulon we arrive at La Pradet Station. It was a more significant stop on the line with passenger facilities, a goods shed, two goods sidings, a passing loop serving two platforms, a 50 cubic-metre water tower and three hydraulic cranes. The Station building still exists, converted into housing it sits close to a cultural centre – “Espace des Arts”, effectively enveloped by it! Little else of the site remains. The first image was taken in 2004 by Jacques Lahitte. The second modern image was taken from Google Streetview in 2017.

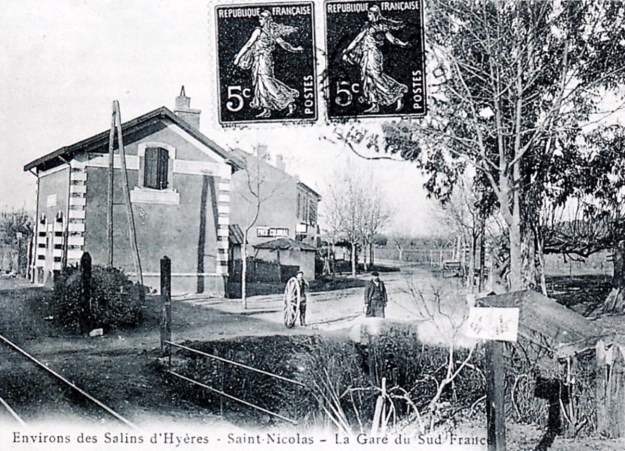

In the image above, Les Salins d’Hyères is in the top right and Hyères Station can be seen in the top left. The tight radius as the line approaches the coast is clearly visible centre-bottom of the image below the airport.

In the image above, Les Salins d’Hyères is in the top right and Hyères Station can be seen in the top left. The tight radius as the line approaches the coast is clearly visible centre-bottom of the image below the airport.

These two pictures show the station after closure and the cycle track which replaced the railway alongside the coast road. The following picture shows a hotel and the airport. The line of the railway is still visible alongside the coast road.

These two pictures show the station after closure and the cycle track which replaced the railway alongside the coast road. The following picture shows a hotel and the airport. The line of the railway is still visible alongside the coast road.