One branch of the Chemin de Fer du Sud Littoral extended from La Foux Les Pins to Saint-Tropez. The featured satellite image above shows the full route of the tramway from the station at La Foux to St. Tropez. At each end of the line an aerial photo allows us to see what the landscape immediately around each town was like.

The station at La Foux was built with the line from Saint-Raphael and opened in 1889. La Foux Station was known as Cogolin-Saint Tropez until 1894 It was 53 kilometres along the line from Hyères and just 4 metres above sea-level. As a 2nd class station, La Foux had a goods shed, an engine shed capable of stabling two locomotives, two Mason tracks and one goods line. In 1893 two extra tracks were provided for the Cogolin and Saint-Tropez tramways.

The station at La Foux was built with the line from Saint-Raphael and opened in 1889. La Foux Station was known as Cogolin-Saint Tropez until 1894 It was 53 kilometres along the line from Hyères and just 4 metres above sea-level. As a 2nd class station, La Foux had a goods shed, an engine shed capable of stabling two locomotives, two Mason tracks and one goods line. In 1893 two extra tracks were provided for the Cogolin and Saint-Tropez tramways.

The station was one of the most significant on the line between Saint-Raphael and Toulon and one of the busiest. The line to Saint-Tropez left from the South-east end of the station and ran parallel to the single line to Toulon for a few hundred metres. The two lines separated with the Toulon line turning South and the Saint-Tropez line turning East.

The station was one of the most significant on the line between Saint-Raphael and Toulon and one of the busiest. The line to Saint-Tropez left from the South-east end of the station and ran parallel to the single line to Toulon for a few hundred metres. The two lines separated with the Toulon line turning South and the Saint-Tropez line turning East.

Both the main-line and the two branches were metre-gauge lines. The Saint-Tropez line left the Toulon line and followed what is now the D98A. The first halt on the line was Bertaud.

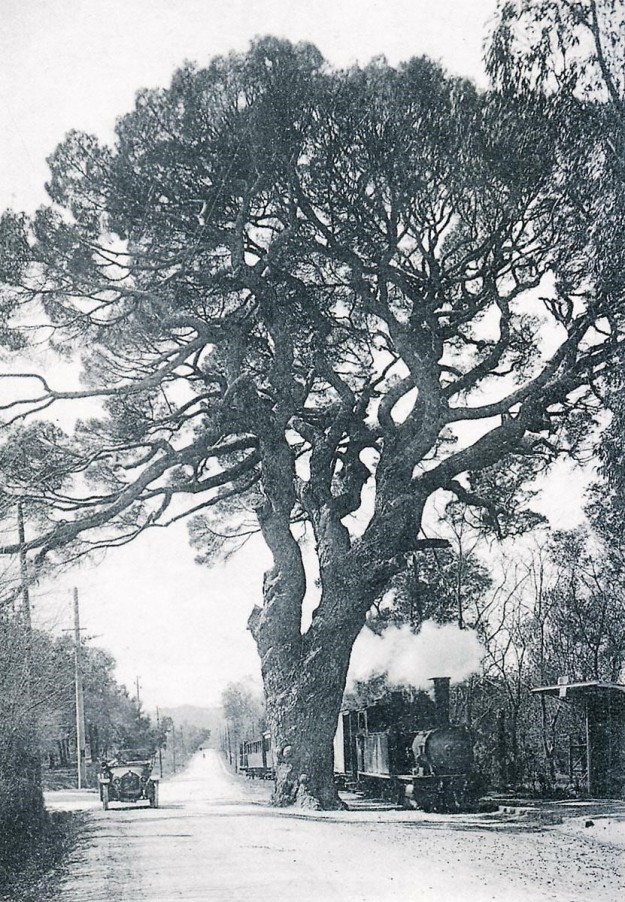

The most famous site on the line to St. Tropez was in the district of Bertaud, where the D98A and the railway passed on either side of a gigantic pine tree. A mixed train from La Foux to St. Tropez stopped at the halt; there is a ballast wagon at the tail which is loaded with wine barrels that will be shipped by boat from the port of Saint-Tropez (Paul CARENCO Collection).

The most famous site on the line to St. Tropez was in the district of Bertaud, where the D98A and the railway passed on either side of a gigantic pine tree. A mixed train from La Foux to St. Tropez stopped at the halt; there is a ballast wagon at the tail which is loaded with wine barrels that will be shipped by boat from the port of Saint-Tropez (Paul CARENCO Collection).

The La Foux – St.Tropez arrives at Bertaud. The train is pulled by 2-4-2T SACM Series 51-56 locomotive and is composed of bogie coaches (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

The La Foux – St.Tropez arrives at Bertaud. The train is pulled by 2-4-2T SACM Series 51-56 locomotive and is composed of bogie coaches (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

A shuttle St.Tropez – La Foux passes under the Bertaud pine. The trunk of this extraordinary tree reached 2.45 metres in diameter and nearly 7.70 metres in circumference; it was unfortunately cut down in 1928 because its roots deformed the railway and road formations (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

A shuttle St.Tropez – La Foux passes under the Bertaud pine. The trunk of this extraordinary tree reached 2.45 metres in diameter and nearly 7.70 metres in circumference; it was unfortunately cut down in 1928 because its roots deformed the railway and road formations (Edmond DUCLOS Collection).

The next stop on the line was that for the torpedo factory. It is marked on the satellite image of the factory by the ‘A’ marker.

The next stop on the line was that for the torpedo factory. It is marked on the satellite image of the factory by the ‘A’ marker.

There was a torpedo factory run by the French Navy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries at St. Tropez. Schneider chose to locate one of its key design facilities in this area and conducted trials here at a centre of research and testing for the Navy. Schneider had their factory along the coast at Les Bormettes.

Norman Friedman [5] tells us that in 1866 British engineer Robert Whitehead invented the first effective self-propelled torpedo, the eponymous Whitehead torpedo. French and German inventions followed closely, and the term torpedo came to describe self-propelled projectiles that travelled under or on water. By 1900, the term no longer included mines and booby-traps as the navies of the world added submarines, torpedo boats and torpedo boat destroyers to their fleets.

Initially, Whitehead’s designs were hampered by their clockwork motor, attached ropes, and surface attack mode, all of which contributed to a slow and cumbersome weapon. However, he kept considering the problem and eventually developed a tubular device, designed to run underwater on its own, and powered by compressed air. The result was a submarine weapon, the Minenschiff (mine ship), the first modern self-propelled torpedo. He presented it officially to the Austrian Imperial Naval commission on 21st December 1866.

The first trials were not successful as the weapon was unable to maintain a course on a steady depth. After much work, Whitehead introduced his “secret” in 1868 which overcame this. It was a mechanism consisting of a hydrostatic valve and pendulum that caused the torpedo’s hydroplanes to be adjusted so as to maintain a pre-set depth.

After the Austrian government decided to invest in the invention, Whitehead started the first torpedo factory in Fiume. In 1870, he improved the devices to travel up to approximately 1,000 yd (910 m) at a speed of up to 6 kn (11 km/h), and by 1881 the factory was exporting torpedoes to ten other countries. The torpedo was powered by compressed air and had an explosive charge of gun-cotton. Whitehead went on to develop more efficient devices, demonstrating torpedoes capable of 18 kn (33 km/h) in 1876, 24 kn (44 km/h) in 1886, and, finally, 30 kn (56 km/h) in 1890.

Royal Navy representatives visited Fiume for a demonstration in late 1869, and in 1870 a batch of torpedoes was ordered. In 1871, the British Admiralty paid Whitehead £15,000 for certain of his developments and production started at the Royal Laboratories in Woolwich the following year. In 1893, RN torpedo production was transferred to the Royal Gun Factory. The British later established a Torpedo Experimental Establishment at HMS Vernon and a production facility at the Royal Naval Torpedo Factory, Greenock in 1910. These are now closed.

The Nordenfelt-class Ottoman submarine Abdülhamid (1886) was the first submarine in history to fire a torpedo while submerged.

Whitehead opened a new factory near Portland Harbour, England in 1890, which continued making torpedoes until the end of the Second World War. Because orders from the RN were not as large as expected, torpedoes were mostly exported. A series of devices was produced at Fiume, with diameters from 14 in (36 cm) upward. The largest Whitehead torpedo was 18 in (46 cm) in diameter and 19 ft (5.8 m) long, made of polished steel or phosphor bronze, with a 200-pound (91 kg) gun-cotton warhead. It was propelled by a three-cylinder Brotherhood engine, using compressed air at around 1,300 psi (9.0 MPa) and driving two contra-rotating propellers, and was designed to self-regulate its course and depth as far as possible. By 1881, nearly 1500 torpedoes had been produced. Whitehead also opened a factory at St Tropez in 1890 that exported torpedoes to Brazil, Holland, Turkey and Greece.

Whitehead purchased rights to the gyroscope of Ludwig Obry in 1888 but it was not sufficiently accurate, so in 1890 he purchased a better design to improve control of his designs, which came to be called the “Devil’s Device”. The firm of L. Schwartzkopff in Germany also produced torpedoes and exported them to Russia, Japan and Spain. In 1885, Britain ordered a batch of 50 as torpedo production at home and at Fiume could not meet demand.

By World War I, Whitehead’s torpedo remained a worldwide success, and his company was able to maintain a monopoly on torpedo production. By that point, his torpedo had grown to a diameter of 18 inches with a maximum speed of 30.5 knots (56.5 km/h; 35.1 mph) with a warhead weighing 170 pounds (77 kg).

The French naval torpedo factory at Toulon made Whitehead torpedoes under license. Given its limited output, the French also bought torpedoes directly from Whitehead (Fiume) by 1898 they had ordered 206 after sixty-four had been delivered. About 1905, the French turned to Schneider their main arms company, to produce torpedoes. Schneiders torpedo plant was at Les Bormettes near Hyères. When a US officer visited Schneider in 1913, he commented that the company was clearly finding it difficult to meet Whitehead’s competition. Schneider managed to secure small orders from France and Italy, and in 1913 these torpedoes were running their range trials.

Schneider claimed that they were exceeding requirements. At the same time the prevailing opinion at the French government plant at Toulon was that Schneider had failed to prove superiority over Whitehead, and it was unlikely that they could compete. As for Whitehead, because the property at Fiume physically limited the company’s expansion, in 1913 it built a large new plant at St. Tropez. near Toulon. Whitehead saw the new plant as an extension of its Fiume operation, and definitely not as a plant to fill French government orders. Customers eventually included Brazil, Greece, the Netherlands and Turkey.

Schneider claimed that they were exceeding requirements. At the same time the prevailing opinion at the French government plant at Toulon was that Schneider had failed to prove superiority over Whitehead, and it was unlikely that they could compete. As for Whitehead, because the property at Fiume physically limited the company’s expansion, in 1913 it built a large new plant at St. Tropez. near Toulon. Whitehead saw the new plant as an extension of its Fiume operation, and definitely not as a plant to fill French government orders. Customers eventually included Brazil, Greece, the Netherlands and Turkey.

Michel Goujon [6] says that in 1912, the English firm Whitehead built a torpedo factory at the bottom of the Gulf of Saint-Tropez, on the site of the castle Bertaud which was not destroyed but integrated into the industrial buildings. The site was accessible to ships of significant tonnage. Prototype production began in 1917 during the First World War. In 1936, the Popular Front decided to nationalize the factory because its production was highly strategic for the country. From 1937 it became a Navy establishm ent and its torpedo’s became critical to, from 1937. establishment of the Navy. Its torpedoes armed many submarines under the French flag. Amazing activity, only a stone’s throw from one of the most glamorous harbours on the planet.

ent and its torpedo’s became critical to, from 1937. establishment of the Navy. Its torpedoes armed many submarines under the French flag. Amazing activity, only a stone’s throw from one of the most glamorous harbours on the planet.

The factory was built on the immediate site of the castle Bertaud.

In the image below, workers from the torpedo factory wait for the train at the end of their shift.

The factory has recently been sold by the privatised company which took it on when the Navy gave it up.

The next stop after the Torpedo Factory was Oustalet-dei-Pescadous a good few hundred metres along the coast. Then Château-Martin, Sinopolis, Maleribes and then La Bouillabaisse, all of which have disappeared in the time since the line closed. A railcar is stopped at La Bouillabaisse in the photograph below.

Another short distance and the train stopped once again, this time at Le Pilon, its last stop be fore Saint-Tropez. The stagecoach from St. Tropez to Ramatuelle passes through Pilon. The railway can be seen alongside (GECP Collection).

Another short distance and the train stopped once again, this time at Le Pilon, its last stop be fore Saint-Tropez. The stagecoach from St. Tropez to Ramatuelle passes through Pilon. The railway can be seen alongside (GECP Collection).

The same location. The image shows that sand has been used for ballast at Le Pilon (Raymond BERNARDI Collection).

From Le Pilon, the line entered Saint-Tropez and approached the terminus on the quayside. The layout of the terminus is shown in the plan superimposed on the satellite image by Jean-Pierre Moreau [3].

From Le Pilon, the line entered Saint-Tropez and approached the terminus on the quayside. The layout of the terminus is shown in the plan superimposed on the satellite image by Jean-Pierre Moreau [3].

As can be seen in the above image, the original harbour at St. Tropez is much changed and there has been significant land reclamation to enlarge facilities at the port. The aerial photographs below show the port in the time around the closure of the line. Those images are followed by a sequence of photographs culled from the research of Jean-Pierre Moreau [3].

As can be seen in the above image, the original harbour at St. Tropez is much changed and there has been significant land reclamation to enlarge facilities at the port. The aerial photographs below show the port in the time around the closure of the line. Those images are followed by a sequence of photographs culled from the research of Jean-Pierre Moreau [3].

St.Tropez terminus buildings with an open wagon stabled under the loading gauge of the goods shed (Raymond BERNARDI Collection)

St.Tropez terminus buildings with an open wagon stabled under the loading gauge of the goods shed (Raymond BERNARDI Collection)

This image is taken from roughly the same position in the 21st Century. The station building has been replaced by the town Post Office!

This image is taken from roughly the same position in the 21st Century. The station building has been replaced by the town Post Office!

In this view of St.Tropez station around 1910, you can see on the left the access track to the port (René SENNEDOT Collection).

In this view of St.Tropez station around 1910, you can see on the left the access track to the port (René SENNEDOT Collection).

Here, a team of CP railway workers pose in front of the 4-6-0T Pinguely No. 66 locomotive shunting a mixed train in St.Tropez station. The two windows on the rear of the cab, probably all too frequently broken by the heating tools, were closed by sheet metal plates pierced with a circular hole to allow some visibility in the cabin forward (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – Pierre LECROULANT collection).

Here, a team of CP railway workers pose in front of the 4-6-0T Pinguely No. 66 locomotive shunting a mixed train in St.Tropez station. The two windows on the rear of the cab, probably all too frequently broken by the heating tools, were closed by sheet metal plates pierced with a circular hole to allow some visibility in the cabin forward (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – Pierre LECROULANT collection).

In the 1930s, station-master Marcel Cauvin (second from the left) poses in St.Tropez station with the driver, fireman and guard of locomotive 4-6-0T Pinguely No. 66 (Pierre VIROT Collection).

In the 1930s, station-master Marcel Cauvin (second from the left) poses in St.Tropez station with the driver, fireman and guard of locomotive 4-6-0T Pinguely No. 66 (Pierre VIROT Collection).

The station-master, the driver, the mechanic, the postmaster, and the conductor pose close to the point lever on one of the passenger tracks and beside a 2-4-2T Series 51-56 locomotive at the St. Tropez station (Pierre LECROULANT Collection).

The station-master, the driver, the mechanic, the postmaster, and the conductor pose close to the point lever on one of the passenger tracks and beside a 2-4-2T Series 51-56 locomotive at the St. Tropez station (Pierre LECROULANT Collection).

A coach from the lot built by SF workshops, Frejus in 1908: C-2504 is seen in the years 1925-30 at St. Tropez. (Pierre VIROT Collection).

A coach from the lot built by SF workshops, Frejus in 1908: C-2504 is seen in the years 1925-30 at St. Tropez. (Pierre VIROT Collection).

In December 1923, a 2-4-2T SACM 51-56 locomotive, started by mistake by an inexperienced night watchman, ended up in the water of St. Tropez harbour! We see it here the day after this incident, with a 4-6-0T Pinguely series 41-44 trying to get it back on track (Jean-Pierre VIGUIE Collection).

In December 1923, a 2-4-2T SACM 51-56 locomotive, started by mistake by an inexperienced night watchman, ended up in the water of St. Tropez harbour! We see it here the day after this incident, with a 4-6-0T Pinguely series 41-44 trying to get it back on track (Jean-Pierre VIGUIE Collection).

The mixed passenger-goods building at St. Tropez terminus seen after its expansion (GECP Collection).

The mixed passenger-goods building at St. Tropez terminus seen after its expansion (GECP Collection).

An 0-6-0T Corpet-Louvet series 70 to 72 manoeuvres along the goods platform at St. Tropez Station. Due to the lack of a turntable, these locos were always oriented cabin Cogolin side and chimney St. Tropez (Pierre VIROT Collection).

An 0-6-0T Corpet-Louvet series 70 to 72 manoeuvres along the goods platform at St. Tropez Station. Due to the lack of a turntable, these locos were always oriented cabin Cogolin side and chimney St. Tropez (Pierre VIROT Collection).

The small locomotive shed at the Station is seen in 1925, with the loading gauge and a view of the back of a departing mixed train to La Foux (Collection François MORENAS).

The small locomotive shed at the Station is seen in 1925, with the loading gauge and a view of the back of a departing mixed train to La Foux (Collection François MORENAS).

The first railcar to return to St. Tropez station after the war, during the summer of 1945: a normal train (motor + trailer) tows a second train, consisting of two trailers recovered from trains whose motorcar was out of service. This train ensured that workers could get from the surrounding area to the Torpedo factory (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – Pierre LECROULANT collection)

The first railcar to return to St. Tropez station after the war, during the summer of 1945: a normal train (motor + trailer) tows a second train, consisting of two trailers recovered from trains whose motorcar was out of service. This train ensured that workers could get from the surrounding area to the Torpedo factory (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – Pierre LECROULANT collection)

Women constituted up to 30% of the staff of the Littoral network, they were often the wife of an agent of the Railway, like the mail carrier Emilie Cauvin that we see here in front of a railcar in station of St.Tropez, on 10th January 1946. Very unusually it has snowed! (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – Hidalgo ARNERA collection).

Women constituted up to 30% of the staff of the Littoral network, they were often the wife of an agent of the Railway, like the mail carrier Emilie Cauvin that we see here in front of a railcar in station of St.Tropez, on 10th January 1946. Very unusually it has snowed! (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – Hidalgo ARNERA collection).

The closure of the line from La Foux to St. Tropez was suspended for one year to continue to pick up workers from the Bertaud torpedo factory. The service continued until 4th June 1949. This is one of the last trains visiting St. Tropez accompanied by the conductor Marcel Vinciguerra, towing an old bogie car (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – GECP collection).

The closure of the line from La Foux to St. Tropez was suspended for one year to continue to pick up workers from the Bertaud torpedo factory. The service continued until 4th June 1949. This is one of the last trains visiting St. Tropez accompanied by the conductor Marcel Vinciguerra, towing an old bogie car (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – GECP collection).

A quick look round the port of St. Tropez!

A quick look round the port of St. Tropez!

The modern post of St. Tropez has a capacity of 734 moorings divided between two basins on an area of nine hectares in the heart of the village, Saint-Tropez harbour is a main port of call in the Mediterranean. It is one of the most famous marinas in the world. In a very small area racing boats sit alongside large pleasure yachts, the fishing boats which used to be so prominent have sadly disappeared along with the railway that served the village until 1949.

The modern post of St. Tropez has a capacity of 734 moorings divided between two basins on an area of nine hectares in the heart of the village, Saint-Tropez harbour is a main port of call in the Mediterranean. It is one of the most famous marinas in the world. In a very small area racing boats sit alongside large pleasure yachts, the fishing boats which used to be so prominent have sadly disappeared along with the railway that served the village until 1949.

In this final picture, all the buildings of the former St. Tropez Station are still in place at the edge of the harbour and the town; the tracks have been dismantled but the route to the harbour can still clearly be distinguished heading left (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – GECP collection).

References

[1] Roland Le Corff; http://www.mes-annees-50.fr/Le_Macaron.htm, accessed 13th December 2017.

[2] Marc Andre Dubout; http://marc-andre-dubout.org/cf/baguenaude/toulon-st-raphael/toulon-st-raphael1.htm, accessed 14th December 2017

[3] Jean-Pierre Moreau; http://moreau.fr.free.fr/mescartes/ToulonGareSudFrance.html, accessed 24th December 2017.

[4] José Banaudo; Histoire des Chemins de Fer de Provence – 2: Le Train du Littoral (A History of the Railways of Provence Volume 2: The Costal Railway); Les Éditions du Cabri, 1999.

[5] Norman Friedman; Naval Weapons of World War One; Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley, December 2011.

[6] Michel Goujon; L’autre Saint-Tropez; Michel Lafon, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, 2017.

Pingback: Ligne du Littoral (Toulon to St. Raphael) – Part 15 – November 2018 Visits to the Line (Chemins de Fer de Provence 81) | Roger Farnworth