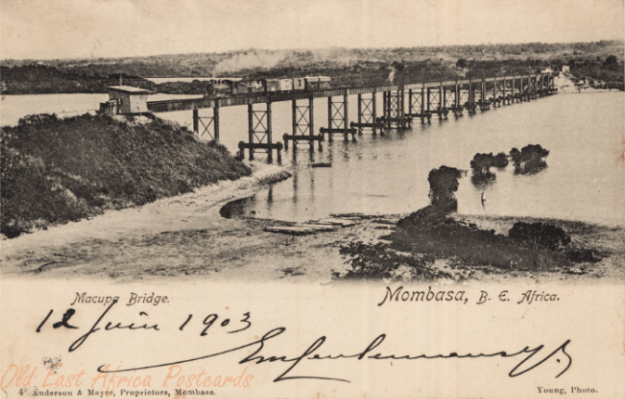

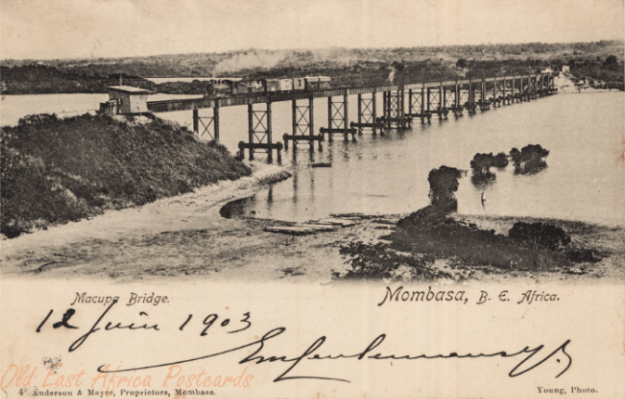

Although the featured image bears the title ‘Zanzibar’ it is actually a picture of an early wooden trestle bridge on the Uganda Railway at Mombasa. The picture is probably taken in 1899.[1] The card itself is dated 1901. The pictures were taken by Coutinho Bros. Photographers of Zanzibar. The picture of the railway is taken from “the lead in to the wooden trestle bridge built across the creek for the Uganda Railway between Mombasa Island and the mainland in 1896.”[2] This only remained in service for a short time, being replaced by an iron pile bridge, which itself was only in service until the 1920s. Pictures of this iron bridge are shown below. The crossing was called the Macupa (Salisbury) Bridge. The first picture was taken in 1903, the second in 1909 …

More about the History of the network of Metre-Gauge Railways in East Africa

A. Uganda Railway: The Uganda Railway was, first of all, a means of reaching Lake Victoria from Mombasa. Construction of the railway line started, as we have noted in the first post in this series,[3] just before the turn of the 20th Century. The Uganda Railway Company lasted until 1927 when it was reorganised and renamed as the Kenya-Uganda Railways & Harbours Company.

The terminus at Lake Victoria was called Port Florence and was named for the wife of the railway engineer, Ronald Preston. On 20th December 1901, Mrs Florence Preston took a hammer to symbollically drive in the last spike of the last rail immediately on the shore of the Lake.[4]

Within a year the name of the settlement had reverted to that given by the Luo people. The Luo called it ‘Kisumo’ (a good place to look for food). Kisumu was not the first port used by the British on the East coast of Lake Victoria. They first established Port Victoria, but by 1898, British explorers decided that the location of Kisumu was favourable. It was at the cusp of the Winasm Gulf and at the end of caravan trails from Pemba, Mombasa and Malindi and had great potential for access by lake steamers.

Within a year the name of the settlement had reverted to that given by the Luo people. The Luo called it ‘Kisumo’ (a good place to look for food). Kisumu was not the first port used by the British on the East coast of Lake Victoria. They first established Port Victoria, but by 1898, British explorers decided that the location of Kisumu was favourable. It was at the cusp of the Winasm Gulf and at the end of caravan trails from Pemba, Mombasa and Malindi and had great potential for access by lake steamers.

Almost from its inception the Uganda Railway developed shipping services on Lake Victoria. In 1898, it launched the 110 ton SS William Mackinnon at Kisumu, having assembled the vessel from a kit supplied by Bow, McLachlan and Company of Paisley in Scotland. A succession of further Bow, McLachlan & Co. kits followed. The 662 ton sister ships SS Winifred and SS Sybil (1902 and 1903), the 1,134 ton SS Clement Hill (1907) and the 1,300 ton sister ships SS Rusinga and SS Usoga (1914 and 1915) were combined passenger and cargo ferries. The 812 ton SS Nyanza (launched after Clement Hill) was purely a cargo ship. The 228 ton SS Kavirondo launched in 1913 was a tugboat. Two more tugboats from Bow, McLachlan were added in 1925: SS Buganda and SS Buvuma.[1],[5],[6]

The amazing story of the delivery and construction of the SS William Mackinnon is covered elsewhere but is worth reading. The ship was dismantled into a series of parts, all but two of which were less than the weight designated for an individual porter. The parts made their way across the interior by porter long before the railway was completed.[7]

Boats, ships and steamers are not the main focus of this post, so let’s get back on track! Here are two images of the railway which I have found on another WordPress blog.[8]. The first shows construction in progress the second shows the railway passing through a small local settlement.

Boats, ships and steamers are not the main focus of this post, so let’s get back on track! Here are two images of the railway which I have found on another WordPress blog.[8]. The first shows construction in progress the second shows the railway passing through a small local settlement.

There is an excellent collection of photographs relating to the construction of the Uganda Railway on this link:

There is an excellent collection of photographs relating to the construction of the Uganda Railway on this link:

https://www.theeagora.com/the-lunatic-express-a-photo-essay-on-the-uganda-railway

Just a few of those images are reproduced here … three examples include the arrival of the line at its first station out of Mombasa, Chamgamwe, just 6 miles out of Mombasa. It was opened on 15th December 1897.

Voi (below) was 100 miles from Mombasa.

Voi (below) was 100 miles from Mombasa.

Nairobi Station was 326 miles from Mombasa and is shown in old postcard pictures below.

The railway continued through a series of smaller stations to Kisumu. Once the railway reached Kisumu, access to Lake Victoria was transformed, and an 11-kilometre (7 mile) rail line between Port Bell and Kampala was the final link in the chain providing efficient transport between the Ugandan capital and the open sea at Mombasa, more than 1,400 km (900 miles) away.[1]

Branch lines were built to Tikka in 1913, Lake Magadi in 1915, Kitale in 1926, Naro Moro in 1927 and from Tororo to Soroti in 1929. Lake Magadi provided a strong commercial interest as it proved to be an excellent place for harvesting naturally occuring soda.

Lake Magadi is the southernmost lake in the Kenyan Rift Valley, lying in a catchment of faulted volcanic rocks, north of Tanzania’s Lake Natron. During the dry season, it is 80% covered by soda and is well known for its wading birds, including flamingos, it is a saline, alkaline lake, approximately 100 square kilometres in size and an example of a “saline pan”. The lake water, which is a dense sodium carbonate brine, precipitates vast quantities of the mineral trona (sodium sesquicarbonate). In places, the salt is up to 40 metres thick. The lake is recharged mainly by saline hot springs (temperatures up to 86 °C) that discharge into alkaline “lagoons” around the lake margins.[8]

I enjoyed a visit to the soda works at Lake Magadi in 1994, sadly by car and not by train!

The Soda Works

A soda train on the Magadi branch in Kenya

Theeagora.com refers to the Uganda Railway as ‘The Lunatic Express’, as do a number of different sources.[1],[9] It was first given a similar moniker as early as the late 19th Century. The Uganda Railway faced a great deal of criticism in the British Parliament, as many MPs felt that the railway was a Lunatic Line:

What is the use of it, none can conjecture,

What it will carry, there is none can define,

And in spite of George Curzon’s superior lecture,

It is clearly naught but a lunatic line.

— Henry Labouchère, MP, [1],[10]

“Political resistance to this “gigantic folly”, as Henry Labouchère called it,[1],[11] surfaced immediately. Such arguments along with the claim that it would be a waste of taxpayers’ money were easily dismissed by the Conservatives. Years before, Joseph Chamberlain had proclaimed that, if Britain were to step away from its “manifest destiny”, it would by default leave it to other nations to take up the work that it would have been seen as “too weak, too poor, and too cowardly” to have done itself.[1],[12] Its cost has been estimated by one source at £3 million in 1894 money, which is more than £170 million in 2005 money,[1],[13] and £5.5 million or £650 million in 2016 money by another source.”[1],[14]

“Because of the wooden trestle bridges, enormous chasms, prohibitive cost, hostile tribes, men infected by the hundreds by diseases, and man-eating lions pulling railway workers out of carriages at night, the name “Lunatic Line” certainly seemed to fit. Winston Churchill, who regarded it “a brilliant conception”, said of the project: “The British art of ‘muddling through’ is here seen in one of its finest expositions. Through everything—through the forests, through the ravines, through troops of marauding lions, through famine, through war, through five years of excoriating Parliamentary debate, muddled and marched the railway.””[1],[15]

The modern term Lunatic Express was coined by Charles Miller in his 1971 “The Lunatic Express: An Entertainment in Imperialism.” [9]

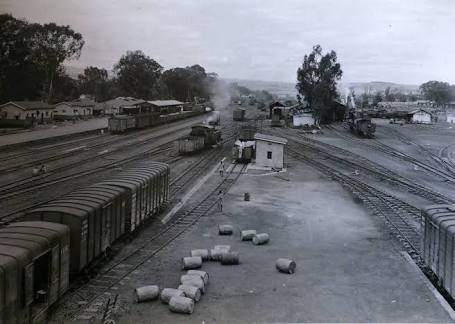

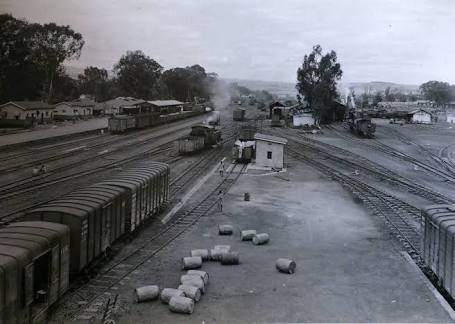

B. Kenya-Uganda Railways and Harbours: In 1927 the Uganda Railway was transformed into Kenya-Uganda Railways & Harbours by the British colonial administration. The railway system in Kenya & Uganda operated in this guise until 1948. during this time the railway system was further expanded. In 1931, a branch line was completed to Mount Kenya and a significant extension to the mainline was made from Nakuru to Kampala in Uganda. This line made the route to Kisumu less significant. Nakuru Station had significant marshalling yards.  The first image is an early picture of the station and its sidings. The second picture shows the station building built in the mid-1950s. This new station was opened on 14th June 1957 by the then Governor of Kenya Sir Eveleyn

The first image is an early picture of the station and its sidings. The second picture shows the station building built in the mid-1950s. This new station was opened on 14th June 1957 by the then Governor of Kenya Sir Eveleyn  Baring. As can be seen it was of an architectural style redolent of buildings in the UK in the 1950s.

Baring. As can be seen it was of an architectural style redolent of buildings in the UK in the 1950s.

C. East African Railways and Harbours – 1948 to 1966: in 1948, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania came under the same British Colonial Administration. Following the terms of the Versailles Treaty in 1919 Germany lost all her colonies worldwide. The colonies became the mandate territories of the League of Nations (currently United Nations). Victorious nations surrounding the mandate territories were allowed to administer them on behalf of the League of Nations. The railways of the three colonies/ protectorates were amalgamated.

D. East African Railways Corporation – 1966 to 1978: following independence, the three East African Presidents Jomo Kenyatta, Julius Nyerere and Milton Obote met in Arusha and came up with the Arusha declaration in 1966. In the declaration, it was resolved that efficiency in parastatals needed to be improved. One of the parastatals identified for reform was East African Railways & Harbours. It was decided in this meeting that harbours be divorced from the railways administration. This was done purely for the purpose of efficiency. In 1969, the name changed to East African Railways Corporation.

E. Kenya Railways Corporation, Uganda Railways Corporation and Tanzania Railways Corporation – 1978-2006: by the late 1970s, the distrust between the three East African leaders, Nyerere, Kenyatta and Idi Amin had reached fever pitch. This was partly due to the different political ideologies that the three leaders practiced. Additionally, Nyerere and Amin believed that Kenya was benefiting more from the East African Community than Tanzania and Uganda. Personal differences between the three leaders culminated in the break-up of the East African Community in 1977. The break up led to the birth of Kenya Railways, Uganda Railways & Tanzania Railways as separate entities.

F. Rift Valley Railways – 2006 to 2017: Rift Valley Railways (RVR) took over the operations of the Kenya and Uganda Railways on 1st November, 2006. RVR was established on October 14, 2005, when the Government of Kenya and the Government of Uganda jointly tendered through a bidding process, a 25 year concession for the rehabilitation, operation and maintenance of the railways then run by Kenya Railways Corporation (KRC) and Uganda Railways Corporation (URC) respectively. The concession was terminated in October 2017.[16]

G. Uganda Railways Corporation – 2017 to …….: The railways of Uganda and Kenya are now back under government control. Kenya is already developing a standard gauge railway system and it is very possible that with Chinese investment , a standard gauge system will extend across Uganda and Tanzania into Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. There may be more about this in a future post.

G. Uganda Railways Corporation – 2017 to …….: The railways of Uganda and Kenya are now back under government control. Kenya is already developing a standard gauge railway system and it is very possible that with Chinese investment , a standard gauge system will extend across Uganda and Tanzania into Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. There may be more about this in a future post.

The existing lines within Uganda are in the hands of a renewed Uganda Railways Corporation. The transfer finally occurred in February 2018.[18] Commuter services in Kampala are due to resume in 2018, now that the railway is back in Ugandan hands.

References

1. Wikipedia, Uganda Railway; https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uganda_Railway, accessed on 6th May 2018.

2. Old East Africa Postcards; http://www.oldeastafricapostcards.com/?page_id=2352, accessed 7th May 2018.

3. https://rogerfarnworth.wordpress.com/2018/05/09/uganda-railways-part-1.

4. AllAfrica.com; A Hundred Years Down the Drain; http://allafrica.com/stories/200110220533.html, accessed 9th May 2018.

5. Stuart Cameron, David Asprey & Bruce Allan; SS Buganda. Clyde-built Database, accessed on 22nd May 2011.

6. Stuart Cameron, David Asprey & Bruce Allan; SS Buvuma. Clyde-built Database, accessed on 22nd May 2011.

7. Ian H. Grant; Nyansa Watering Place, the Remarkable Story of the SS. William MacKinnon; The British Empire; https://www.britishempire.co.uk/article/nyanzawateringplace.htm, accessed on 9th May 2018.

8. Wikipedia, Lake Magadi; https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Magadi, accessed on 9th May 2018.

9. Theeagora.com, The Lunatic Express; https://www.theeagora.com/the-lunatic-express-a-photo-essay-on-the-uganda-railway,accessed on 9th May 2018; & Charles Miller, The Lunatic Express – An Entertainment in Imperialism; The History Book Club, 1971.

10. Peter Muiruri, End of road for first railway that defined Kenya’s history; The Standard; https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001241674/end-of-road-for-first-railway-that-defined-kenya-s-history, accessed on 9th May 2018.

11. Henry Labouchère. “UGANDA RAILWAY [CONSOLIDATED FUND]. HC Deb 30 April 1900 vol 82 cc288-335”. Hansard 1803–2005. UK Parliament. Retrieved 10 March 2012. I am opposed entirely to this sort of railway in Africa, and I have been opposed to this railroad from the very commencement because it is a gigantic folly. . . . This railroad has been, from the very first commencement, a gigantic folly.

12. Joseph Chamberlain. “CIVIL SERVICES AND REVENUE DEPARTMENTS ESTIMATES, 1894–5: CLASS V. HC Deb 01 June 1894 vol 25 cc181-270”. Hansard 1803–2005. UK Parliament, accessed on 10th March 2012.

13. Currency converter; The National Archives, accessed on 10th March 2012.

14. Daniel Knowles; The lunatic express. 1843; The Economist, 23rd June 2016, accessed on 15th July 2016.

15. Winston Spencer Churchill,; My African Journey; William Briggs, Toronto, 1909, p4-5.

16. Uganda, Kenya, failed railway deal, (Rift Valley Railways); The Monitor; http://www.monitor.co.ug/Business/Markets/Uganda–Kenya-failed-railway-deal—RVR-chief/688606-4140902-15aa6p0/index.html, accessed on 10th May 2018.

17. Isaac Khisa; The Independent (Kampala) AllAfrica.com, Uganda Railways is back! http://allafrica.com/stories/201708140089.html, accessed on 10th May 2018.

18. Amos Ngwomwoya; “Passenger train services to resume on Monday”. Daily Monitor. Kampala, 23rd February 2018, accessed on 10th May 2018 & Alfred Ochwo, and Mercy Ahukana (27 February 2018). “Kampalans welcome revamped passenger train services”. The Observer (Uganda), Kampala, 27th February 2018, accessed on 10th May 2018.

Class 59 Garratt No. 5902, Ruwenzori Mountains takes on water at Voi Station.

Class 59 Garratt No. 5902, Ruwenzori Mountains takes on water at Voi Station.  Voi Station Sign. [1]

Voi Station Sign. [1] An old colonial-era railway line sits near the site of the new Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway line under construction in Voi, Kenya. Bloomberg photo by Riccardo Gangale.[8]

An old colonial-era railway line sits near the site of the new Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway line under construction in Voi, Kenya. Bloomberg photo by Riccardo Gangale.[8] EAR Class 59 Garratt No. 5902 “Ruwenzori Mountains” heads away from Voi with a Mombasa to Nairobi Goods train on 10th December 1976 © Bingley Hall, on flickr.[2]

EAR Class 59 Garratt No. 5902 “Ruwenzori Mountains” heads away from Voi with a Mombasa to Nairobi Goods train on 10th December 1976 © Bingley Hall, on flickr.[2] Class 59, 5914 at the same location. [5]

Class 59, 5914 at the same location. [5] The map shows the branch-line to Moshi as a dotted line turning away from the A109 and following the A23 to the bottom left of the image. The route is bridged by the SGR. The next two images are taken of trains on that branch-line. Both show the same locomotive, Class 60 Garratt No. 6013, © CPH 3 on flickr.[3]

The map shows the branch-line to Moshi as a dotted line turning away from the A109 and following the A23 to the bottom left of the image. The route is bridged by the SGR. The next two images are taken of trains on that branch-line. Both show the same locomotive, Class 60 Garratt No. 6013, © CPH 3 on flickr.[3]

Class 59 Garratt en-route to Voi – © James Waite.[4]

Class 59 Garratt en-route to Voi – © James Waite.[4] Irima Railway Station.

Irima Railway Station. Ndi Railway Station.

Ndi Railway Station. Manyani © Thomas Roland on Flickr [6]

Manyani © Thomas Roland on Flickr [6]

An image from google maps. [7]

An image from google maps. [7]

The metre-gauge line crosses a relatively low level bridge over the Tsavo River, just beyond Tsavo Station, which can be seen in the next few images, the first of which is taken from the A109 bridge over the Tsavo River.

The metre-gauge line crosses a relatively low level bridge over the Tsavo River, just beyond Tsavo Station, which can be seen in the next few images, the first of which is taken from the A109 bridge over the Tsavo River.

Class 59 Garratt, 5903 Mount Meru, on Tsavo Bridge, heading towards Voi – © James Waite.[4]

Class 59 Garratt, 5903 Mount Meru, on Tsavo Bridge, heading towards Voi – © James Waite.[4]

Another shot of the bridge. [6]

Another shot of the bridge. [6]

It supersedes the station on the old metre-gauge line, although that line may well remain open for goods traffic.[9]

It supersedes the station on the old metre-gauge line, although that line may well remain open for goods traffic.[9] Darajani, © Matthew O’Connor on flickr. [11]

Darajani, © Matthew O’Connor on flickr. [11]

The last three sepia pictures are courtesy of the UK National Archive. [12]

The last three sepia pictures are courtesy of the UK National Archive. [12] Plan of Makindu Station and sidings.[12] The following photos are from Dr Gurraj Singh Jabal [14] and a few other sources.

Plan of Makindu Station and sidings.[12] The following photos are from Dr Gurraj Singh Jabal [14] and a few other sources.

There was a rail accident at Makindu on 29th March 1958.

There was a rail accident at Makindu on 29th March 1958.

Kima. [9]

Kima. [9]

Kalembwani. [9]

Kalembwani. [9]

Ulu. [9]

Ulu. [9] Ulu. [15]

Ulu. [15]

As the line turned to the north it was joined by a branch which served the Chamgamwe Oil Refinery to the south. Next came the first station on the line at Chamgamwe. The photographs of this station from the 1960s and 1970s are courtesy of Malcolm McCrow’s website [3] and are copyright Malcolm McCrow and Kevin Patience.

As the line turned to the north it was joined by a branch which served the Chamgamwe Oil Refinery to the south. Next came the first station on the line at Chamgamwe. The photographs of this station from the 1960s and 1970s are courtesy of Malcolm McCrow’s website [3] and are copyright Malcolm McCrow and Kevin Patience.