Locomotives on the Kenya and Uganda Railway and Harbours Lines (1927- 1948)

In 1926/27 the Uganda Railway was replaced first by the Kenya and Uganda Railways in 1926 and then by the Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbours (KURH) Corporation in 1927, when the powers-that-be placed Mombasa Harbour into the same company as the railways.

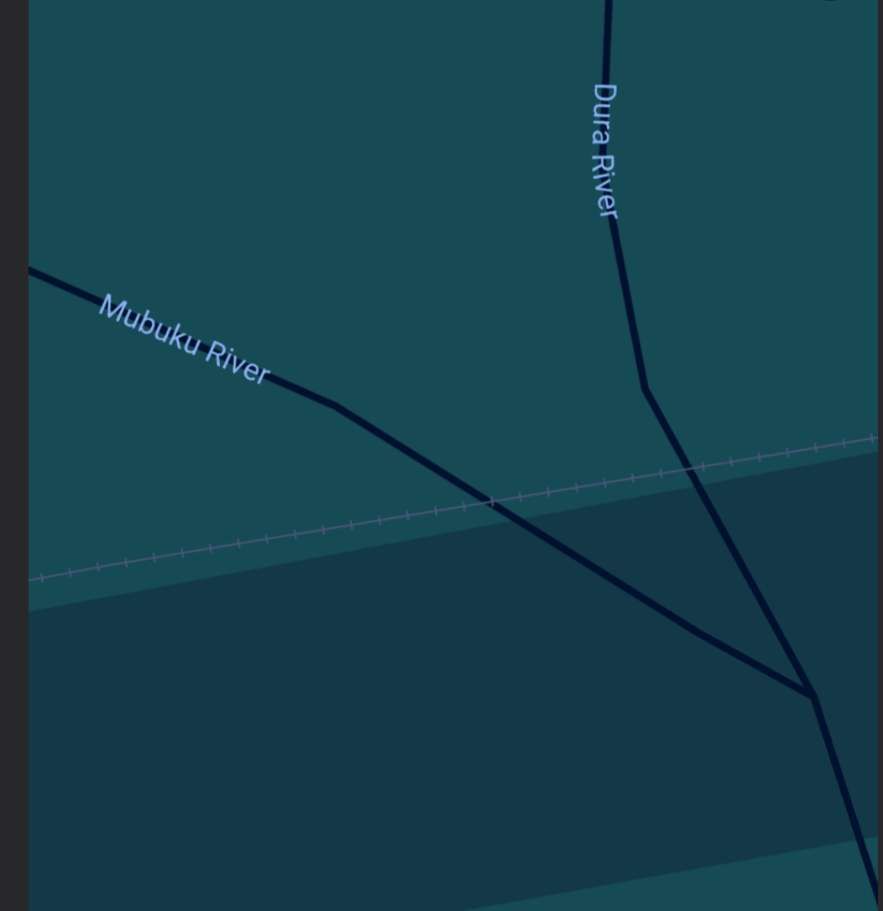

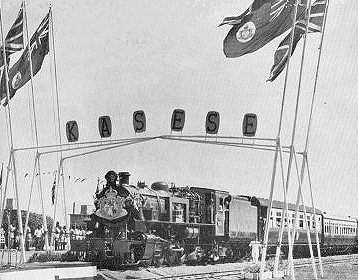

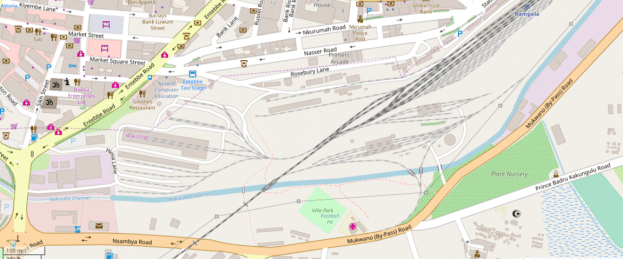

Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbours (KURH) ran harbours, railways and lake and river ferries in Kenya Colony and the UgandaProtectorate until 1948. It included the Uganda Railway, which it extended from Nakuru to Kampala in 1931. In the same year it built a branch line to Mount Kenya. [1]

In 1948, it was merged with the Tanganyika Railway to form the East African Railways and Harbours Corporation which provided rail, harbour and inland shipping services in all three territories until the High Commission’s successor, the East African Community, was dissolved by its member states in 1977. [1]

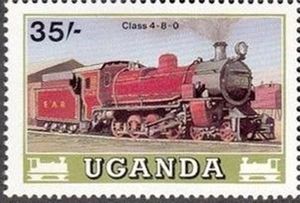

The EB3 Class, later Class 24

One of the most reliable of classes on the system were the old EB3 Class which eventually became EAR Class 24. They were numbered 2401-2462 by the EAR and served right through the KURH tenure of the railway system. As noted in the last post, these were 4-8-0 locomotives. The last of the three pictures of this Class, and the largest (below) shows one of the Class at Nairobi Railway Museum in the mid-1980s (© torgormaig on the National Preservation Forum). [11] This locomotive was originally given a Class number of 2412 but when No. 2401 was made a Ugandan loco as part of the arrangements for the devolution of the East African Railways into their constituent countries, No. 2412 was renumbered No. 2401 in Kenya.

One of the most reliable of classes on the system were the old EB3 Class which eventually became EAR Class 24. They were numbered 2401-2462 by the EAR and served right through the KURH tenure of the railway system. As noted in the last post, these were 4-8-0 locomotives. The last of the three pictures of this Class, and the largest (below) shows one of the Class at Nairobi Railway Museum in the mid-1980s (© torgormaig on the National Preservation Forum). [11] This locomotive was originally given a Class number of 2412 but when No. 2401 was made a Ugandan loco as part of the arrangements for the devolution of the East African Railways into their constituent countries, No. 2412 was renumbered No. 2401 in Kenya.

In addition to these locos, the UR bequeathed a series of different locos to the KUR: including its MS Class of 2-6-4T locomotives which became the KUR EE Class and eventually the EAR Class 10; its GC Class which became the KUR EB2 Class; its G Class which became the KUR GA Class and later still, the KUR EB Class.

The KUR went on to order a series of powerful locomotives:

The EA Class, later Class 28

The KURH EA class, later known as the EAR 28 class, were 2-8-2 steam locomotives. The six members of the class were built in 1928 for the Kenya-Uganda Railway by Robert Stephenson and Company in Darlington, England, and were later operated by the KURH’s successor, the East African Railways (EAR). [2][3]

The KURH EA class, later known as the EAR 28 class, were 2-8-2 steam locomotives. The six members of the class were built in 1928 for the Kenya-Uganda Railway by Robert Stephenson and Company in Darlington, England, and were later operated by the KURH’s successor, the East African Railways (EAR). [2][3]

Iain Mulligan took a number of photographs of this class of locomotives. One of a Class 28 taking on furness fuel oil at Nairobi MPD. The 28 Class were the largest non-articulated locomotives on the system. Mulligan also shows No. 2804 Kilifi being prepared for service at Nairobi Shed. [4]

Built by Messrs R Stevenson in 1928, they were originally designated the EA Class by the KUR&H. With their 4ft 3in driving wheels, these 2-8-2s looked far more like the locomotives built for the UK home market and looked distinctly un-African. East African Railways – EAR Class 28 (KURH – EA Class) 2-8-2 steam locomotive Nr. 2801 “Mvita” (Robert Stephenson Locomotive Works 3921 / 1928). [5] The ex-works photograph for this Class is below. [6]

East African Railways – EAR Class 28 (KURH – EA Class) 2-8-2 steam locomotive Nr. 2801 “Mvita” (Robert Stephenson Locomotive Works 3921 / 1928). [5] The ex-works photograph for this Class is below. [6]

The EA Class were well-liked by drivers and firemen. They initially worked the mail trains between Nairobi and Mombasa and by 1950 had completed a million miles. Unfortunately, they were relegated to hauling goods trains at high speed and as this resulted in significant mechanical troubles which led to their withdrawal in the 1960s (c) Kevin Patience. [15]

The EA Class were well-liked by drivers and firemen. They initially worked the mail trains between Nairobi and Mombasa and by 1950 had completed a million miles. Unfortunately, they were relegated to hauling goods trains at high speed and as this resulted in significant mechanical troubles which led to their withdrawal in the 1960s (c) Kevin Patience. [15]

The East African Railways and Harbours Magazine carried a single page article on the Class 28 locos in 1955. [7]

The East African Railways and Harbours Magazine carried a single page article on the Class 28 locos in 1955. [7]

The EC Class Garratts

The KUR EC class was a class of 4-8-2+2-8-4 Garratt-type articulated steam locomotives. The four members of the class, built by Beyer, Peacock & Co. in Manchester, England, were the first Garratts to be ordered and acquired by the Kenya-Uganda Railway (KUR). [3]. They entered service in 1926, and, after a relatively short but successful career with the KUR, were sold and exported to Indo-China in August 1939. [8] They became the forebears of a dynasty of power -massive locomotives working on narrow-gauge rails, functioning best because they were articulated and could spread their power and weight over a significant number of axles.

The ED1 Class, later Class 11

The KUR ED1 class was a class of 2-6-2T steam locomotives built for the Kenya-Uganda Railway (KUR). The 27 members of the ED1 class entered service on the KUR between 1926 and 1930. They were later operated by the KUR’s successor, the East African Railways (EAR), and reclassified as part of the EAR 11 class.[3]

In 1930, four similar locomotives were built for the Tanganyika Railway (TR) as the TR ST class. These locomotives differed from the ED1 class units only in being fitted with vacuum brake equipment instead of Westinghouse brakes and air compressor. They, too, were later operated by the EAR, and reclassified as part of the EAR’s 11 class.[3][9]

The two images above show KUR ED1 Class which later became EAR Class 11. [10]

The two images above show KUR ED1 Class which later became EAR Class 11. [10] The ED1 locomotives were the last locomotives to be supplied to the network without superheaters. At first they were used on branch-line traffic, but later in life they could be seen on shunting duties across the whole network, (c) Kevin Patience. [15]

The ED1 locomotives were the last locomotives to be supplied to the network without superheaters. At first they were used on branch-line traffic, but later in life they could be seen on shunting duties across the whole network, (c) Kevin Patience. [15]

The EC1 Class Garratts, later EAR Class 50 and 51

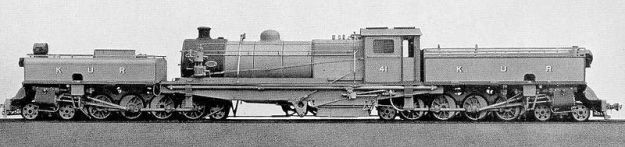

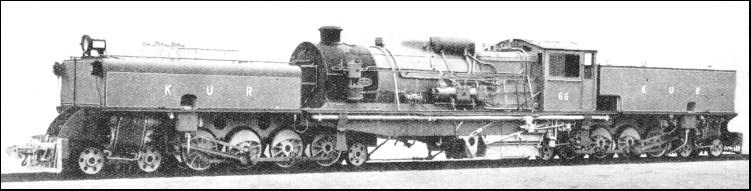

The KUR EC1 class, later known as the EAR 50 class and the EAR 51 class were also 4-8-2+2-8-4 Garratt-type articulated steam locomotives. The KURH numbered these locomotive No. 45 to No. 66. The EAR numbered them 5001 to 5018 and 5101, 5102. The last of the class is shown in the works photos below.

The first twenty members of the class were built in 1927 by Beyer, Peacock & Co. in Manchester, England, for the Kenya-Uganda Railway (KUR). They entered service in 1928, and, with two exceptions, were later operated by the KUR’s successor, the East African Railways (EAR), as its 50 class. [3][12] The two exceptions were sold to Indo-china in the late 1930s.

The first twenty members of the class were built in 1927 by Beyer, Peacock & Co. in Manchester, England, for the Kenya-Uganda Railway (KUR). They entered service in 1928, and, with two exceptions, were later operated by the KUR’s successor, the East African Railways (EAR), as its 50 class. [3][12] The two exceptions were sold to Indo-china in the late 1930s.

The remaining two members of the EC1 class were built and entered service in 1930, and were different in some respects. They later became the EAR’s 51 class. [3][12] KUR No 54 ‘Nandi’ departing Nairobi with a passenger train (c) Andrew Templer. Class EC1 No 54 was to become EAR&H 50 Class 5008. [13]

KUR No 54 ‘Nandi’ departing Nairobi with a passenger train (c) Andrew Templer. Class EC1 No 54 was to become EAR&H 50 Class 5008. [13] KUR Postcard showing KUR Class EC1 still in grey but sporting EAR&H 50 Class number board as it heads a Nairobi bound freight over the Mau Summit. The locomotive number of the 50 Class was also illuminated on either side of the headlight, (c) EAR&H Magazine. [14]

KUR Postcard showing KUR Class EC1 still in grey but sporting EAR&H 50 Class number board as it heads a Nairobi bound freight over the Mau Summit. The locomotive number of the 50 Class was also illuminated on either side of the headlight, (c) EAR&H Magazine. [14]

The EC2 Class Garratts, later EAR Class 52

The KUR EC2 class, later known as the EAR 52 class, was also a class 4-8-2+2-8-4 Garratt-type locomotives. There were 10 members of the Class. KUR ordered them unusually from the North British Locomotive Company in Glasgow, Scotland, instead of Beyer, Peacock & Co., the builder of all the KUR’s other Garratt locomotives. They entered service in 1931, and were later operated by the KUR’s successor, the East African Railways (EAR), both in Kenya/Uganda and in Tanzania. [3] Source: the Beyer Garratt website (www.beyergarrattlocos.co.uk). The picture is annotated as follows: Kenya-Uganda Railway class EC2 – No. 68 (NBL 24071/1931) as East African Railways 5202. (Chris Greville collection). [16]

Source: the Beyer Garratt website (www.beyergarrattlocos.co.uk). The picture is annotated as follows: Kenya-Uganda Railway class EC2 – No. 68 (NBL 24071/1931) as East African Railways 5202. (Chris Greville collection). [16] An EC2 at Nairobi Shed. After working for some years on the Kenya Uganda lines, theory moved to the Central Line and were eventually scrapped in the late 1960s, (c) Kevin Patience. [15]

An EC2 at Nairobi Shed. After working for some years on the Kenya Uganda lines, theory moved to the Central Line and were eventually scrapped in the late 1960s, (c) Kevin Patience. [15]

The EC3 Class Garratts, later EAR Class 57

The KUR EC3 class, later known as the EAR 57 class, was a class of 4-8-4+4-8-4 Garratt-type articulated steam locomotives. The twelve members of the class were built by Beyer, Peacock & Co. in Manchester, England, for the Kenya-Uganda Railway (KUR). They entered service between 1939 and 1941, and were later operated by the KUR’s successor, the East African Railways (EAR). [3][19]

The Class was numbered No. 77 to No. 88 on the KUR. The EAR numbered these locos as No. 5701 to 5712. There is an excellent article on-line about the making of a G-Scale model of No.77 ‘Mengo’. [20]

These were the first locomotives anywhere in the world built with the 4-8-4+4-8-4 wheel arrangement. “The huge boiler and extended wheel arrangement that this system of articulation permits is noteworthy, and the fact that the engine is to operate on a 50-lb. rail, has a maximum axleload of less than 12 tons, and can negotiate a 275-ft. radius curve, yet weighs 186 tons, makes this locomotive a conspicuous example, of the designing capacity and ingenuity of the British locomotive manufacturer. The Kenya & Uganda Railways have

These were the first locomotives anywhere in the world built with the 4-8-4+4-8-4 wheel arrangement. “The huge boiler and extended wheel arrangement that this system of articulation permits is noteworthy, and the fact that the engine is to operate on a 50-lb. rail, has a maximum axleload of less than 12 tons, and can negotiate a 275-ft. radius curve, yet weighs 186 tons, makes this locomotive a conspicuous example, of the designing capacity and ingenuity of the British locomotive manufacturer. The Kenya & Uganda Railways have

used Garratt engines for many years, and before long the 879 miles of main-line will be operated almost entirely by this type of engine, which is an indication of the state of reliability and availability it has attained, and how it can give to a railway restricted by a narrow gauge and light rail the carrying capacity of a standard-gauge railway.” [21]

Designed by Beyer, Peacock & Co. Ltd. to the detailed specification of the Chief Mechanical Engineer, Mr. K. C. Strahan …, and the subsequent requirements of Mr. H. B. Stoyle, then present Chief Mechanical Engineer (1939) and previously Locomotive Running Superintendent

of the railway, these locomotives were the next step in a significant series of Garratt locomotives supplied to the Kenya & Uganda Railways. “Perhaps nowhere in the world have Garratt engines been worked more intensively, the mileages obtained being a record for a narrow-gauge line of this kind. The new design not only embodie[d] the makers‘ improvements

culled from the experience of Garratts in service in various parts of the world, but include[d] various modifications and alterations suggested by the railway, based on its long experience,

which combine[d] to make these new engines particularly interesting and outstanding

examples.” [22]

The locomotives are massive, particularly, “considering the restrictive conditions of a metre-gauge and 50-lb. rail. On this light rail (half the weight of the rail in Great Britain) and on a gauge 1 ft. 5 1/8 in. less with more difficult grade and curvature conditions, the tractive effort of the engine is equal to the biggest passenger engines in Great Britain while the boiler is practically equal in horsepower, having a similar size grate and an even larger barrel diameter despite the total height to chimney top from rail level of 12 ft. 5 1/2 in., which is nearly a foot lower

than the highest British dimension. The locomotive further weighs roughly 20 tons more than the largest British types, the width over the running board is 9 ft. 6 in., and the footplate area is

considerably larger than that of many standard gauge engines.” [22]

Interestingly it was specified that these engines were designed to, “facilitate conversion

to 3 ft. 6 in. gauge with the minimum of alteration; thus the cylinders and rods and motion are centred for the wider gauge, a wider wheel centre providing for the shifting of the tyres

outwards. The engine [was also] designed to take care of the possible conversion of the Westinghouse brake to vacuum, when the gauge is altered, and also for the ultimate introduction of automatic couplers. Despite these features, however, a far greater measure

of accessibility [was] obtained throughout the locomotive than hitherto.” [22]

The full design details for these engines can be obtained from the July 1939 Railway Gazette article. [22] EC3 Class KUR No. 87 ‘Karamoja’ at Nairobi Railway Museum in 2012, [23] and again, below. [24]

EC3 Class KUR No. 87 ‘Karamoja’ at Nairobi Railway Museum in 2012, [23] and again, below. [24]

Details of the Class 57 provided by the EAR&H Magazine. [25]

Details of the Class 57 provided by the EAR&H Magazine. [25] Class 57 No. 5711 on Nairobi shed on 15th January 1971, it lasted another two years before being withdrawn for preservation, © Terry Bagworth. [26]

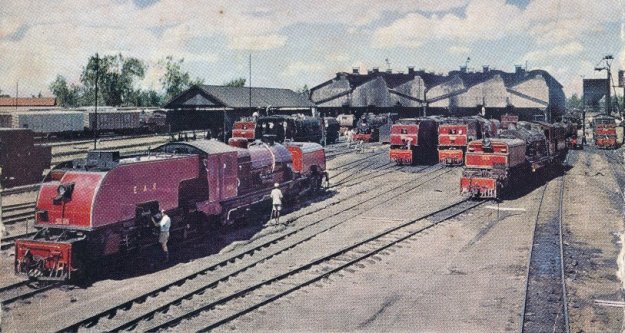

Class 57 No. 5711 on Nairobi shed on 15th January 1971, it lasted another two years before being withdrawn for preservation, © Terry Bagworth. [26] Line-up of East African Railways motive power at Nairobi MPD with 60 Class Garratt 6024 Sir James Hayes Saddler prominent left and 57/58 Class right. Five 59 Class Garratts, two 29 (Tribal) Class and two tank engines are also quite clearly discernable. The post card was probably produced around 1955-6 – EAR&H Postcard via Cliff Rossenrode. [27]

Line-up of East African Railways motive power at Nairobi MPD with 60 Class Garratt 6024 Sir James Hayes Saddler prominent left and 57/58 Class right. Five 59 Class Garratts, two 29 (Tribal) Class and two tank engines are also quite clearly discernable. The post card was probably produced around 1955-6 – EAR&H Postcard via Cliff Rossenrode. [27]

The EC4 Class Garratts, later EAR Class 54

The KUR EC4 class, later known as the EAR 54 class, was a class of 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) gauge 4-8-2+2-8-4 Garratt-type articulated steam locomotives developed under and for use in wartime conditions.

The seven members of the class were built during the latter stages of World War II by Beyer, Peacock & Co. in Manchester, England, for the War Department of the United Kingdom and the Kenya-Uganda Railway (KUR). They entered service on the KUR in 1944, and were later operated by the KUR’s successor, the East African Railways. [28] The official works photograph of a EC4 Class Garratt.

The official works photograph of a EC4 Class Garratt.

Class 54 No. 5407, above, at Nairobi. Formerly the KUR EC4 Class, seven of these powerful Garratts were received in 1944. Despite their impressive tractive effort, the 54s were not a success and were demanding on maintenance and unpopular with footplate crews, © Iain Mulligan. [4]

Class 54 No. 5407, above, at Nairobi. Formerly the KUR EC4 Class, seven of these powerful Garratts were received in 1944. Despite their impressive tractive effort, the 54s were not a success and were demanding on maintenance and unpopular with footplate crews, © Iain Mulligan. [4]

Adjacent, Class 54 Garratt at Nakuru Yard, June 1963, © Neil Rossenrode. [29]

The EC5 Class Garratts, later EAR Class 55

The KUR EC5 class was another class of 4-8-4+4-8-4 Garratts Thet were built during the latter stages o the Second World War at Beyer, Peacock in Gorton, Manchester for the War Department. The two members of the class entered service with the KUR in 1945. They were part of a batch of 20 locomotives, the rest of which were sent to either India or Burma. [3][30]

Class EC5 Garratt, later EAR No. 5505 at the Nairobi Railway Museum in 2012. [30]

Class EC5 Garratt, later EAR No. 5505 at the Nairobi Railway Museum in 2012. [30]

The following year, 1946, four locomotives from that batch were acquired by the Tanganyika Railway (TR) from Burma. They entered service on the TR as the TR GB class. [3]

In 1949, upon the merger of the KUR and the TR to form the East African Railways (EAR), the EC5 and GB classes were combined as the EAR 55 class. In 1952, the EAR acquired five more of the War Department batch of 20 from Burma, where they had been Burma Railways class GD; these five locomotives were then added to the EAR 55 class, bringing the total number of that class to 11 units. [3][30]

Iain Mulligan has two excellent monochrome pictures of one of this class of loco. Class 55 No. 5509 is shown in Nairobi having just arrived from Voi in the two photographs concerned. No. 5509 was ex-Burma Railways. The pictures can be found by following the link in reference [4] No. 5505 on 17th November 1979 shown in KUR grey before it was repainted in EAR maroon. [26]

No. 5505 on 17th November 1979 shown in KUR grey before it was repainted in EAR maroon. [26]

The last locomotives ordered by the KUR were a number of slightly modified EC5 locomotives which were due to be designated as a separate Class – EC6. Indeed these locomotives were designated EC6 by the EAR for a short time before all its locomotives were reclassified.

The next post will look at the locomotives introduced to the network in Kenya and Uganda by the EAR.

References

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kenya_and_Uganda_Railways_and_Harbours, accessed on 17th June 2018.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/KUR_EA_class, accessed on 17th June 2018.

- Roel Ramaer; Steam Locomotives of the East African Railways; David & Charles Locomotive Studies. Newton Abbot, Devon, UK, 1974, p42-85.

- http://www.mccrow.org.uk/EastAfrica/EastAfricanRailways/EARIainMulligan/IainMulliganEAR.htm, accessed on 17th June 2018.

- https://www.google.co.uk/search?q=kenya+railways+class+28&oq=kenya+railways+class+28&aqs=chrome..69i57j33l2.10435j0j8&client=tablet-android-lenovo&sourceid=chrome-mobile&ie=UTF-8#imgrc=Rdg2-uxmx29ZKM: accessed on 17th June 2018.

- https://www.google.co.uk/search?q=kenya+railways+class+28&client=tablet-android-lenovo&prmd=inmv&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiniI7ix9vbAhVlB8AKHdv0CVsQ_AUIESgB&biw=800&bih=1280#imgrc=68XL2N10ywM3aM: accessed on 17th June 2018.

- Staff writer (April 1955). “”28″ Class Locomotive” (PDF). East African Railways and Harbours Magazine. East African Railways and Harbours. Volume 2(2): p57. Accessed on 17th June 2018.

- A. E. Durrant; Garratt Locomotives of the World (rev. and enl. ed.). Newton Abbot, Devon, UK, 1981, p177.

- https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=KUR+ED1+class, accessed on 18th June 2018.

- https://www.radiomuseum.org/museum/eak/railway-museum-nairobi/.html, accessed on 18th June 2018.

- torgormaig on the National Preservation Forum; https://www.national-preservation.com/threads/uganda-railways.1150502/page-2#post-2170907, accessed on 15th June 2018.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/KUR_EC1_class, accessed on 18th June 2018.

- http://www.mccrow.org.uk/EastAfrica/EastAfricanRailways/KURandH.htm, accessed on 18th June 2018.

- Not used

- Kevin Patience; Steam in East Africa; Heinemann Educational Books (E.A.) Ltd., Nairobi, 1976.

- http://www.beyergarrattlocos.co.uk/pics4.html, accessed on 18th June 2018.

- http://www.mccrow.org.uk/EastAfrica/EastAfricanRailways/NairobiMPD.htm, accessed on 18th June 2018.

- Not used.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/KUR_EC3_class, accessed on 19th June 2018.

- http://www.garrattmaker.com/images/home/makingofmengo.pdf, accessed on 19th June 2018.

- The Railway Gazette; 21st july 1939 – Beyer, Peacock & Co. Ltd. Locomotive Engineers Manchester; accessed via ref. [20] above on 19th June 2018.

- The Railway Gazette; 21st july 1939 – New 4-8-4+4-8-4 Metre-Gauge Beyer-Garratt Locomotives, Kenya & Uganda Railways; accessed via ref. [20] above on 19th June 2018.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/KUR_EC3_class, accessed on 19th June 2018.

- https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/613756255442875911, accessed on 19th June 2018.

- Staff writer (February 1955). “”57″ Class Locomotives” (PDF). East African Railways and Harbours Magazine. East African Railways and Harbours. Volume 2 (1): p22, accessed on 19th June 2018.

- http://www.internationalsteam.co.uk/articulateds/garrattsafrica02.htm, accessed on 18th June 2018.

- http://www.mccrow.org.uk/EastAfrica/EastAfricanRailways/NairobiMPD.htm accessed on 1st June 2018.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/KUR_EC4_class, accessed on 19th June 2018.

- https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/462463455481251467, accessed on 19th June 2018.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/KUR_EC5_class, accessed on 19th June 2018.

An Incline was built to move construction materials to the valley floor, two sections of the incline were set at 45 degrees, special cars had to be constructed to carry equipment and in particular locomotives. The incline opened in May 1900 and remained in use until November 1901. Use of the incline advanced the rail-head westward by 170 miles while the line down the escarpment was being built. The pictures immediately adjacent, above and below show the top of the escarpment and two images of a locomotive being lowered to the valley floor. [2]

An Incline was built to move construction materials to the valley floor, two sections of the incline were set at 45 degrees, special cars had to be constructed to carry equipment and in particular locomotives. The incline opened in May 1900 and remained in use until November 1901. Use of the incline advanced the rail-head westward by 170 miles while the line down the escarpment was being built. The pictures immediately adjacent, above and below show the top of the escarpment and two images of a locomotive being lowered to the valley floor. [2]

Class 60 Garratt No. 6023 in Tororo in 1971

Class 60 Garratt No. 6023 in Tororo in 1971

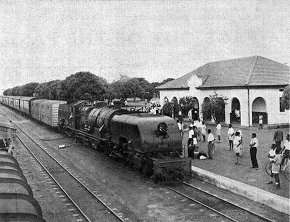

Above: 111497: Aloi Railway Station, Uganda Westbound Passenger Service with No. 2431, © Weston Langford. [3]

Above: 111497: Aloi Railway Station, Uganda Westbound Passenger Service with No. 2431, © Weston Langford. [3]

President Museveni (in hat) in the cab of a lcoc at the commencement of the Rift Valley Railway operations at the weekend in Gulu District (October 2013), (c) Cissy Makumbi. [8]

President Museveni (in hat) in the cab of a lcoc at the commencement of the Rift Valley Railway operations at the weekend in Gulu District (October 2013), (c) Cissy Makumbi. [8] President Museveni flags off a train in Gulu, Uganda. [9]

President Museveni flags off a train in Gulu, Uganda. [9]

The three images of Tororo Station above come from a report by Dr R Choudhuri. [7]

The three images of Tororo Station above come from a report by Dr R Choudhuri. [7]

Bukedea

Bukedea