Unless the LORD builds the house, the builders labour in vain. Unless the LORD watches over the city, the guards stand watch in vain.

Songs of Ascent were usually sung by pilgrims travelling to visit the Temple in Jerusalem. Psalm 127, attributed to Solomon (the builder of the Temple), emphasises that all human efforts — building, security, and labour — are vain without God’s blessing. It highlights the importance of depending on God over self-reliance. It highlights too that children are a divine gift and a source of strength. God’s provision!

Unless the LORD builds the house, the builders labour in vain. … We can imagine the pilgrims heading for Jerusalem looking up from the valley floor, seeing the half-built temple and singing their hearts out. … Unless the LORD builds the house, the builders labour in vain.

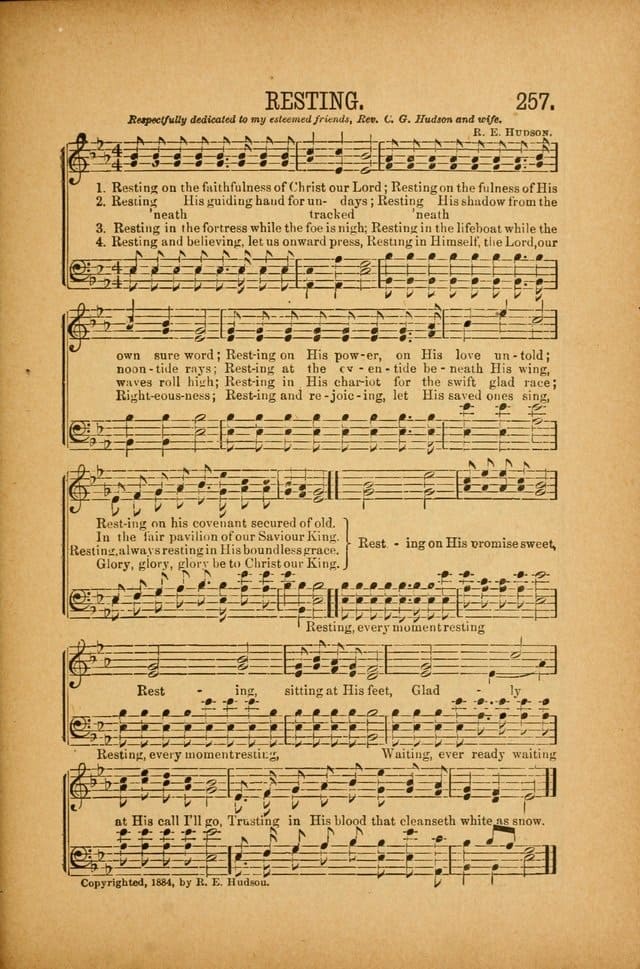

The psalm encourages a life of trust in God’s provision rather than anxious toil or even strident faith. There is a hymn written by Russell Kelso Carter (music by R.E. Hudson) which includes the words ‘Resting on the faithfulness of Christ our Lord’. … The first two verses of the hymn:

Resting on the faithfulness of Christ our Lord,

Resting on the fulness of His own sure word,

Resting on His wisdom, on His love and pow’r,

Resting on His covenant from hour to hour.

Resting ’neath His guiding hand for untrack’d days,

Resting ’neath His shadow from the noontide rays,

Resting at the eventide beneath His wing,

In the glorious presence of our Saviour King.

I guess that this hymn catches something of what the psalm is all about – striving, anxious toil and strident faith are not the same as trusting or resting in the faithfulness of Christ our Lord.

The bible contains plenty of encouragement to trust in God. … From the Old Testament:

We wait in hope for the Lord, he is our help and our shield. In him our hearts rejoice for we trust in his holy name. (Psalm 33: 20-21)

Be still and know that I am God (Psalm 46: 10)

The Lord delights in those who fear him, who put their hope in his unfailing love. (Psalm 147: 11)

Those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles, they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint. (Isaiah 40:31)

Yet this I call to mind and therefore I have hope. Because of the Lord’s great love we are not consumed for his compassions never fail. (Lamentations 3: 21-22)

Just one text from the Gospels:

Jesus said: ‘Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls’. (Matthew 11: 28-29)

But we seem to find it so very difficult to believe that if we rest on God’s promises, if we truly let God be God, then we will see God at work.

It can seem so often that we believe that it is our activity, our strength, our strategies that will bring in God’s kingdom. We seek to serve God’s kingdom by developing mission strategies. We make our plans and we ask God to bless them. We pray before we develop our strategies and we hope that in doing so God will bless our planning.

Don’t hear me wrong, we are called to serve faithfully, to pray in faith, and strategy and vision are important.

But, and it is a big but, our strategies and our vision can take on a life of their own. They can become the be all and end all, they can be seductive, making it feel like we are making progress when perhaps we are not. Our commitment can become first to our vision rather than to the God that we seek to serve.

Our values are permanent or should be. God’s call on our lives is to love as Christ has loved us. Paul, writing to the Philippians says: ‘Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus, who though he was in the form of God did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, … he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross’. Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus. …… Humility, obedience and faithful service are our calling.

These values are permanent. Our strategies and our vision are transitory. Perhaps right for now, but not necessarily for ever. Mission and mission priorities are transitory, but our life in Christ and our faith in God are not.

The hymn again:-

Resting on the faithfulness of Christ our Lord,

Resting on the fulness of His own sure word,

Resting on His wisdom, on His love and pow’r,

Resting on His covenant from hour to hour.

We are called to rest, to place our full weight on, God’s faithfulness to us in Christ. The word used in the original Greek of the New Testament for ‘faithfulness’ and for ‘faith’ is ‘pisteo’. Every time we see the word ‘faith’ or ‘faithfulness’ in the New Testament it is that word ‘pisteo’ or a direct derivative.

We could think about ‘faith’ as something that can be measured. …

So we might say to someone, if only you had enough faith, you would be healed. … If we do so, we are seeing ‘faith’ as something that we might be able to generate ourselves. There is a bible verse which talks of faith moving mountains. I am sure that you will know it. So often this verse is taken to mean that strong belief and determination will allow us to overcome immense obstacles, achieving seemingly impossible things. I guess that if we think like that, we imagine ourselves generating faith, screwing ourselves up to believe.

Just a bit more faith, just a bit more, and we will see God work, we will have healing. … Perhaps we even try to demonstrate our faith by giving more generously, praying more earnestly, serving with greater commitment. But if we see faith this way, we have misunderstood what Jesus was talking about in the bible verse that we partially remembered.

Twice in the Gospels, in Matthew 17:20 and Mark 11:23, Jesus talks about faith as small as a mustard seed being able to move mountains. Mustard seeds are tiny. The very point Jesus is making is that it isn’t the size of our faith that matters but where we place the little faith we have. The Greek word ‘pisteo’ – faith – always means ‘faithfulness’, ‘commitment’ and ‘steadfastness’ – faithfulness and commitment to God in Jesus. It is not focussed on what we can do, nor on how strongly we believe. pisteo-faith is all about the one we have faith in. Mountains in our lives are moved not by the strength of our faith but by the God in whom we trust.

Unless the LORD builds the house, the builders labour in vain.

Pisteo-faith is about faithfully following Jesus, but it is also about something more. It is about resting. …

A chair will illustrate this ………

What do you think of this chair? Is it a beautiful chair?

What is this chair for?

It does not matter so much where a chair comes from or how beautiful a chair is. It does not even matter whether we believe the chair works. … What matters is that we trust that it will hold our weight. It is no good just hovering over it, no good admiring as a beautiful chair, no good being tentative about it. We have to commit wholly to trusting in the chair and resting our weight on it. … Then it does its job.

New Testament pisteo-faith is just like this. We need to wholeheartedly, faithfully, follow Jesus and when we are faithful, when rest our weight on our faith, we will discover that it holds us secure. When we are still. When we let God be God. When we trust in God’s provision. Then figurative mountains will be moved.

Perhaps those pilgrims singing as they travelled to Jerusalem saw the temple under construction and in their songs they acknowledged that everything was in God’s hands, that unless the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it, that nothing worthwhile would be achieved without depending on God, … trusting, resting, faithful. ……

I want to finish with two stories which might encourage us to see that when we rest on God’s promises, when we wait to see what God is doing, when we wait for God to act miracles can occur. I have been in Uganda over the past few weeks. Both of these stories relate to my friends Revd John and Alice Tumusiime in Rukungiri.

A team of 7 of us were in Uganda for much of February 2026. We have had links there for close to 30 years.

We’ve watched what God has been doing in Rukungiri throughout that time. On my first trip there in 1997, I met John and Alice. They and their 4 children had opened their home to 7 or 8 children who were orphans because of the Aids epidemic which was sweeping through Uganda at the time.

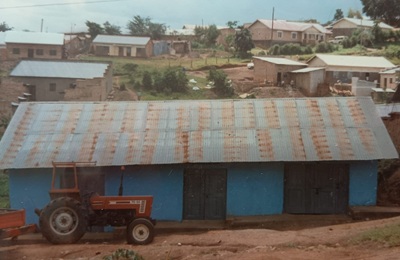

The Bishop of North Kigezi had just given John a plot of land on which to build a school and technical centre. In faith, they built a small building on the land.

In those early years a good number of children started to attend the school. Within a few years there were classes with significant numbers of children in them. This picture is from 1997.

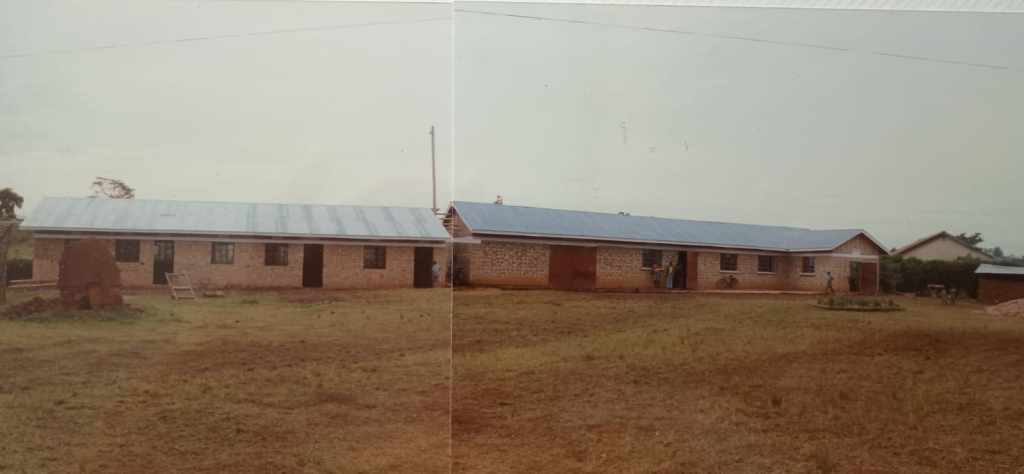

Resources were thin. Mission partners who knew John and Alice, funded a trip to the UK and with visits to a number of churches, there were suddenly a significant number of people offering to fund children’s education in Rukungiri. That small school (Rukungiri Modern Primary School) has developed onto three separate sites – Nursery, Primary and Gables (a technical school). We have had to set up a charity in the UK – Rukungiri Orphan Partnership to manage the sponsorship programme – at any one time we have about 300 children on our sponsorship lists and over the years we have supported at least 7000, probably more, children through their primary education and some through secondary education and university/college.

These are sponsored children from one primary class writing to their sponsors in February 2026.

The school has also provided education for around the same number of paying students. John and Alice will be the first to say that God did this.

Unless the lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it.

My second story comes from our February 2026 trip to Uganda. …

One of our team had experienced dependence on alcohol and drugs. As of March 2026, she is 11 months sober after an encounter with Jesus. She knows the daily struggle that all alcoholics face to remain sober and her faith has made all the difference to her. She felt that God was saying that she should bring Alcoholics Anonymous materials to Rukungiri.

She gave her testimony in church on one Sunday morning.

While we were in Rukungiri she took one person through the 12 steps of the AA programme, she found a couple of people who elsewhere had been involved with the AA and set up the first AA meeting in Rukungiri which will provide a regular support to those seeking to be free of alcohol and drugs. She was able to talk at a mental health clinic and enable medical professionals to understand that drug and alcohol dependency is an illness. She found resources from elsewhere in Uganda in the Rukungiri’s local language (Runyankole-Rukiga) which will support the regular meetings going forward and she id staying in touch with the group via WhatsApp. … A young Christian has made a significant impact, through being faithful, trusting God, resting on God’s promises.

Unless the LORD builds the house, the builders labour in vain.

We are called to be those who depend on God, not on our own resources. We are called to trust in God’s faithfulness. Resting firmly on God’s promises. I am going to finish now with that hymn that I have referred to during this sermon.

Resting on the faithfulness of Christ our Lord,

Resting on the fulness of His own sure word,

Resting on His wisdom, on His love and pow’r,

Resting on His covenant from hour to hour.

Resting ’neath His guiding hand for untrack’d days,

Resting ’neath His shadow from the noontide rays,

Resting at the eventide beneath His wing,

In the glorious presence of our Saviour King.

Resting in the fortress while the foe is nigh,

Resting in the lifeboat while the waves roll high,

Resting in His chariot for the swift, glad race,

Resting, always resting, in His boundless grace.

Resting in the pastures and beneath the Rock,

Resting by the waters where He leads His flock,

Resting, while we listen, at His glorious feet,

Resting in His very arms, oh, rest complete!

Resting and believing, let us onward press;

Resting on Himself, the Lord our righteousness;

Resting and rejoicing, let His saved ones sing,

Glory, glory, glory be to Christ our King!

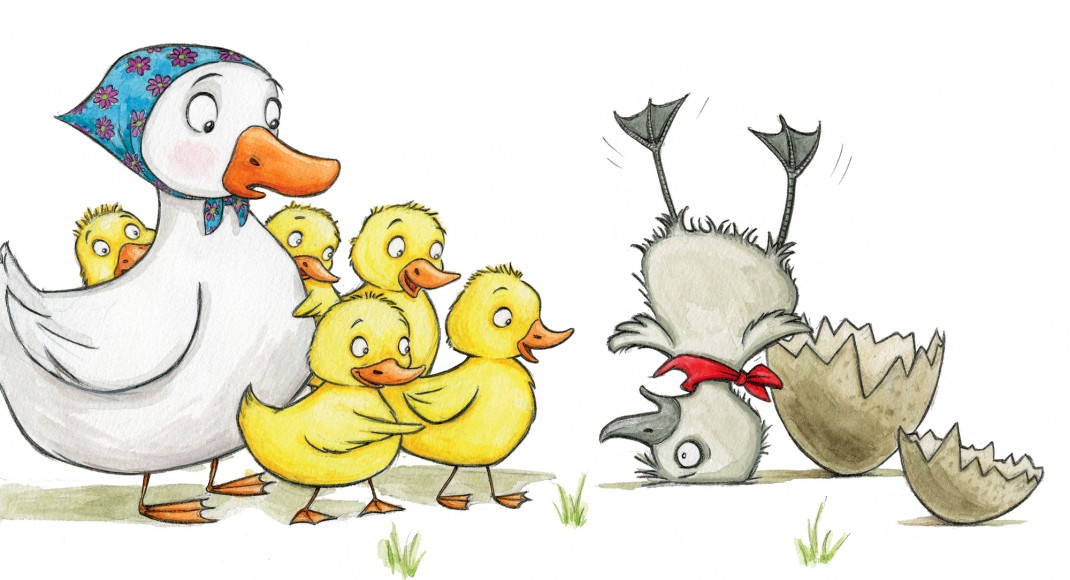

Hans Christian Anderson tells a very familiar story whose main point is that ugly ducklings can become beautiful swans. We know that ugly caterpillars can become amazing butterflies, tadpoles do become frogs and toads. Things do change.

Hans Christian Anderson tells a very familiar story whose main point is that ugly ducklings can become beautiful swans. We know that ugly caterpillars can become amazing butterflies, tadpoles do become frogs and toads. Things do change.