Before resuming our journey along the Whitland & Cardigan Railway, just a few comments about Locomotives and Rolling Stock. …

Locomotives

In early days the line operated with three locomotives. These were all constructed by the same company, Fox, Walker & Co. of Bristol.

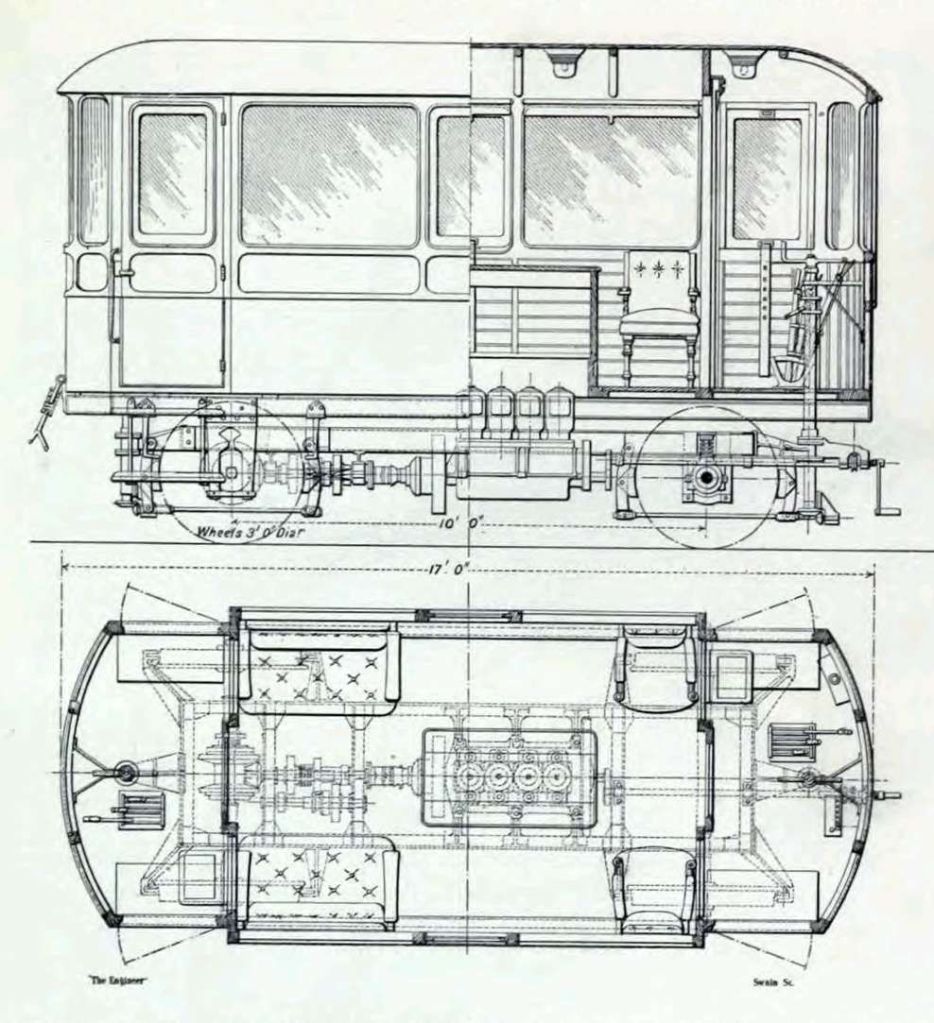

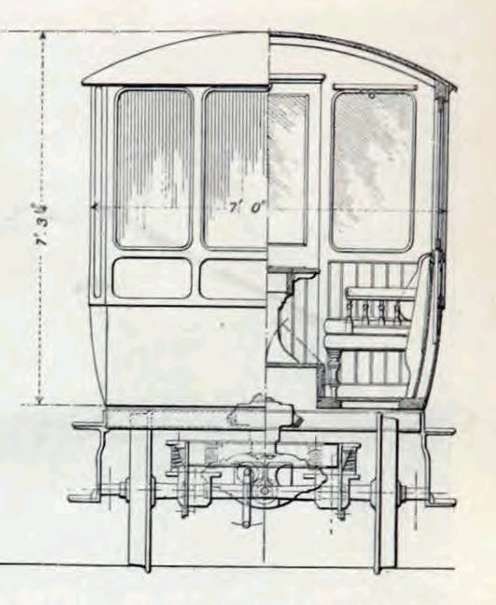

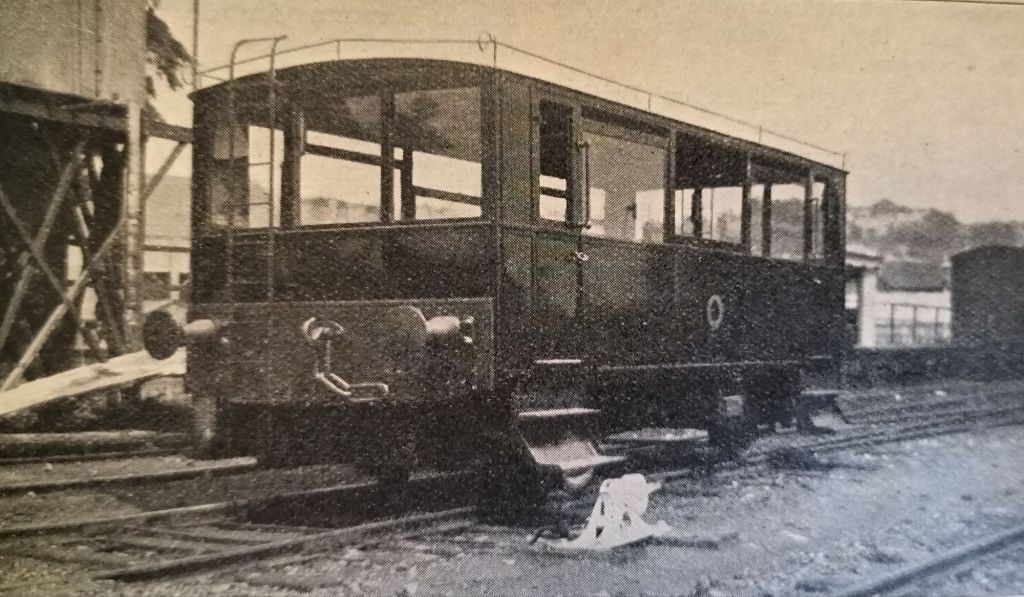

“The company was founded by Francis William Fox and Edwin Walker who opened an engineering works at Atlas Locomotive Works in Bristol in 1864.

They built four and six-coupled saddle tank engines for industrial use. They also built stationary engines and pioneered steam tramcars, the first being tested in Bristol in 1877.

Much of their output was exported.

By 1878 the company had made over 400 small tank engines.

In 1878 they produced six narrow gauge 2-4-2 trench engines for the Royal Engineers at Chatham using Henry Handyside’s steep gradient apparatus. They also produced nine 0-6-0 saddle tank engines for the Somerset and Dorset Railway.

They were taken over by Thomas Peckett in 1880, becoming Peckett and Sons, Atlas Engine Works, Bristol.” [1]

These locomotives were:

No. 1, John Owen, (Works No. 170 of 1872).

No. 2, (Works No. 271 of 1875) – sold by GWR to Bute Works Supply Co., and East Kent Light Railway in 1911. Working until the early 1930s, last known in steam on 22 September 1934, scrapped by September 1935. [10][11][6: p91]

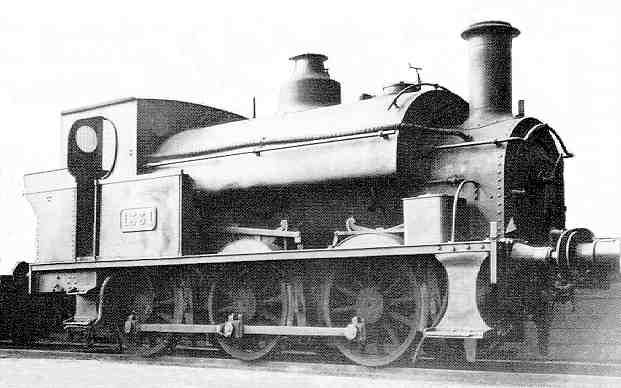

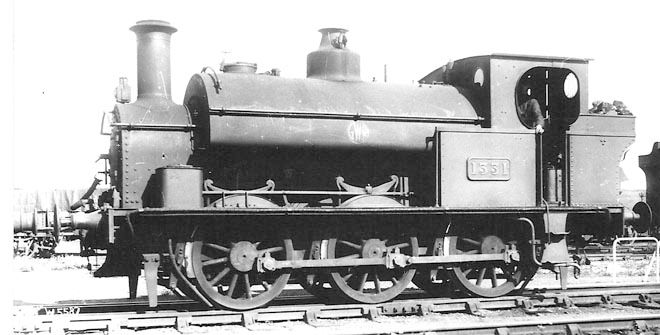

No. 3, (Works No. 340 of 1877) – rebuilt by GWR in 1896; rebuilt again and renumbered 1331 in 1926. Withdrawn in 1950. [11] A story about the building of a model of this locomotive in 00 Gauge can be found here. [12]

https://x.com/JonSLatona/status/1555748042376110080?t=MGZm0QpCXQztdDO4aIYn0A&s=19

Nos. 1 and 2 were 0-6-0ST locos of a similar design. No. 3 was a larger 0-6-0ST locomotive. All three were rebuilt by the GWR. No.1 was rebuilt in 1894. [6: p91]

“Soon after the GWR began operating the railway in 1886, a valuation of W&CR stock was made.No.1 was valued at £450, No. 2 at £600 and No. 3 at £850.” [6: p97]

M.R. Connop Price tells us that:

“Small Great Western tank locomotive types soon put in an appearance and the Whitland and Cardigan engines were moved away. Amongst the designs in evidence at the turn of the century were ’19XX’ 0-6-0 saddle tanks and Armstrong 0-4-2 tanks of ‘517’ class. Pannier tanks were frequently seen as well, but during World War I one of the 0-6-0 saddle tanks, either No. 1939 or No. 1999, was stationed at Cardigan. On the freight side a ‘Dean Goods’ 0-6-0 regularly arrived at Crymmych with the monthly cattle train. This was probably the only working to bring a tender engine onto the branch with any frequency, but tender engines were never common. About 1950 a ‘Dean Goods’ was seen standing on the Cardigan line at Cardigan Junction, in the company of a composite coach and a Siphon ‘G’ van: this is the last known instance of the class on the W&C route. Larger tender locomotives were prohibited by virtue of the line having a yellow colour weight restriction.

For many years ‘2021’ class pannier tanks were active on the line, and between the wars the more powerful ’45XX’ 2-6-2 tank locomotives appeared. These held sway on the Cardigan branch until the complete closure in 1963, although latterly they were supported by more modern pannier tanks in the ’16XX’ series. Amongst the engines seen on the railway in the post-war period were 0-6-0PTs Nos. 2011, 1637, 1648, 1666 and 2-6-2Ts Nos. 4550, 4557, 4569, 5550, 5571. In the final weeks of operation Nos. 4557 and 4569 were the most common performers on the railway.” [6: p99]

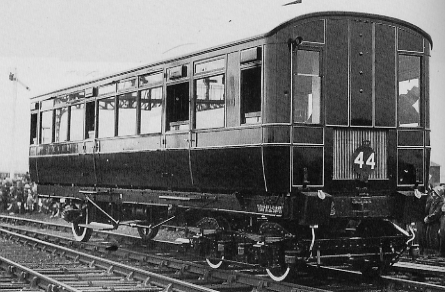

Carriages

Connop Price tells us that, “The Whitland & Taf Vale Railway owned six four-wheeled carriages, all constructed by the Gloucester Wagon Co. The first four were completed in June 1875, and comprised two composite coaches each having a first and two second class compartments, and a luggage compartment. The other two were brake thirds – that is to say comprising three third class compartments and a compartment for the guard. … Two more coaches were supplied by the Gloucester Wagon Co. in September 1875, and these vehicles comprised three third class compartments and a luggage compartment.” [6: p99]

After the GWR takeover of the line, standard GWR coach types began to appear.

Wagons

The Company’s wagons were all constructed by the Bristol Wagon Co. In October 1872, “in anticipation of the opening of the line, the W&TVR ordered a 4-wheel goods brake van and six 4-wheel open goods wagons. … In May 1874, as traffic developed, it was decided to order four more 4-wheel open wagons. … A 4-wheel covered van [was] … Ordered by the company in October 1974, for use on the Crymmych freight service.” [6: p101]

Records of the Gloucester Railway Carriage and Wagon Co. Ltd show that a number of private owner wagons were in use on the line. Connop Price mentions: a five-plank wagon obtained by William Thomas, Coal, Lime & Manure merchant in March 1903; a seven-plank wagon delivered to the Cardigan Mercantile Co. Ltd. in March 1904. A near identical seven-plank wagon was supplied to G.D. Owen, Coal and Lime Merchant of Cardigan in April 1904. Another seven-plank wagon was supplied to S.J. Phillips of Crymmych Arms, Coal and Lime Merchant in September 1908. [6: p101-103]

Connop Price continues: “One other vehicle had a claim to be an item of Cardigan line rolling stock, although at a later date. This was the water tank wagon provided by the GWR in the 1920s or early 1930s to convey water to Cardigan where the supply was sometimes too low to fill the tank. … It was a standard 4-wheel tank wagon, painted white with the initials GW painted in black on the side. The underframe was also black.” [6: p103]

Llanglydwen to Whitland

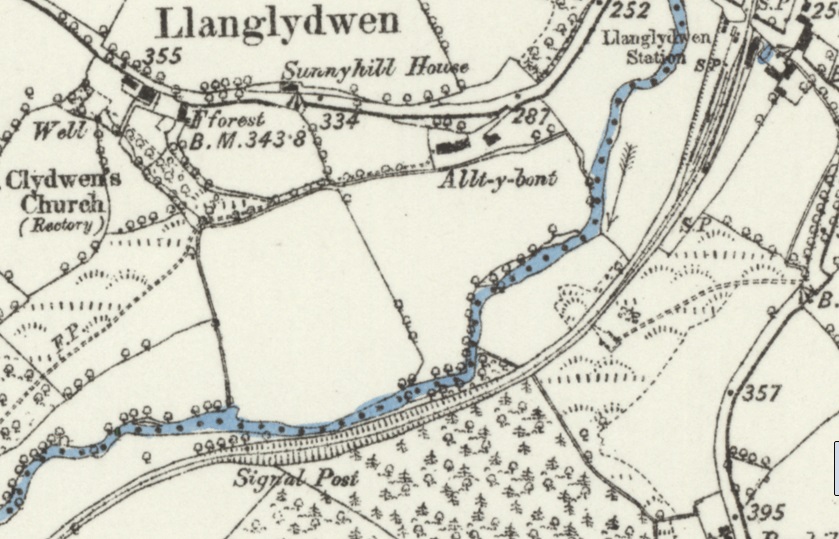

We restart our journey to Whitland at Llanglydwen Railway Station. …

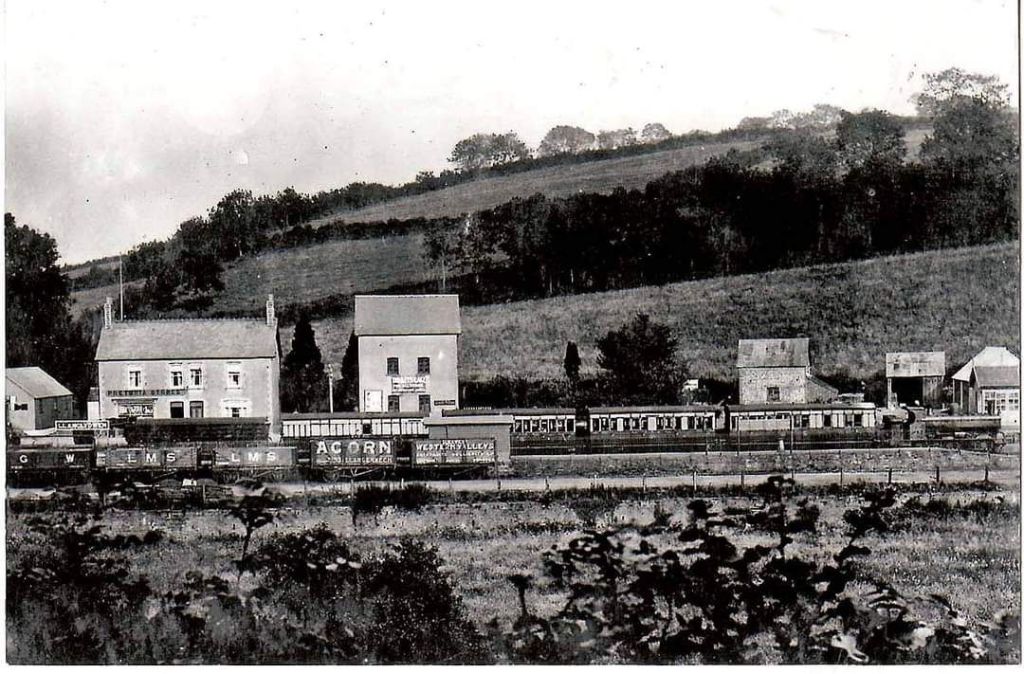

Wikipedia tells that “the original station only had a wooden shed as a station building. A new station was built in 1886. This had a two-storey station building, incorporating the station master’s house, the booking office and a waiting room. The down platform had a timber waiting shelter. Behind this platform was the goods yard, which had one siding. Access to this was enabled by the signal box, which also controlled the level crossing and was at the south end of the up platform. There was also a busy coal yard near the station. The station closed to passengers on 10th September 1962 but remained open for goods until 27th May 1963. The coal depot closed on 2nd February 1963.” [17]

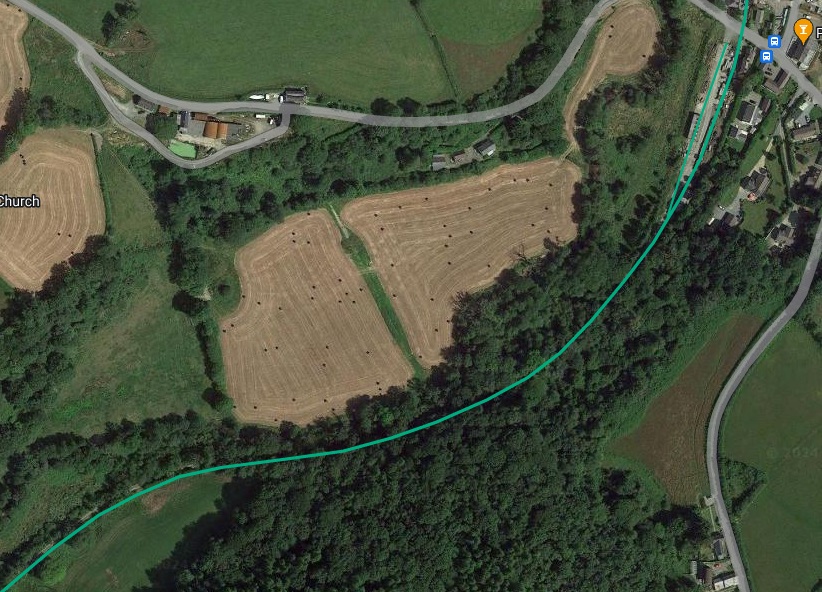

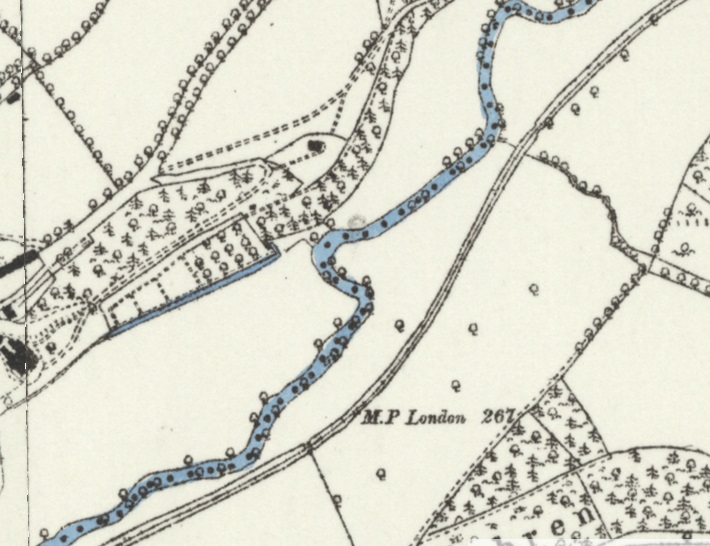

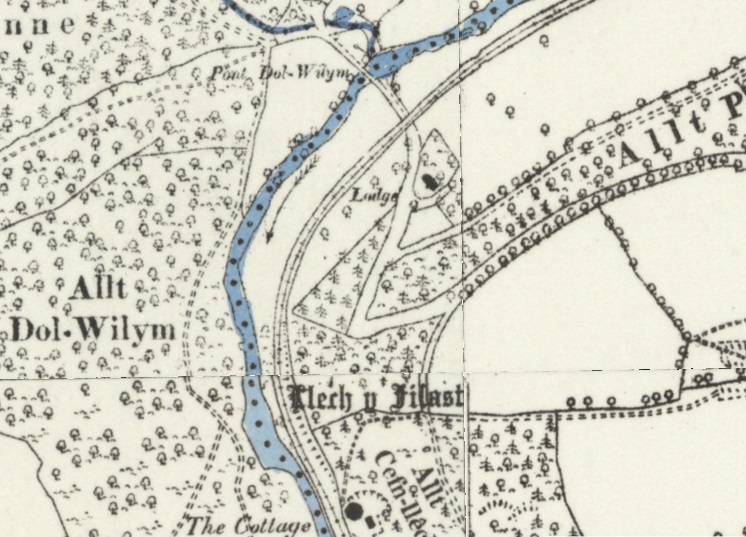

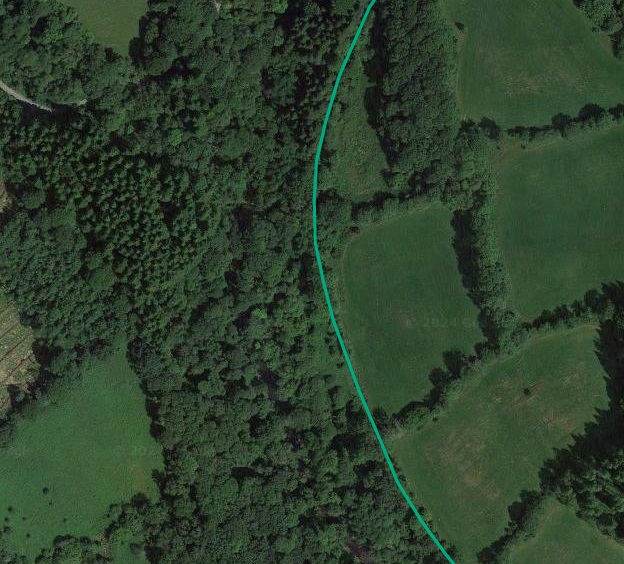

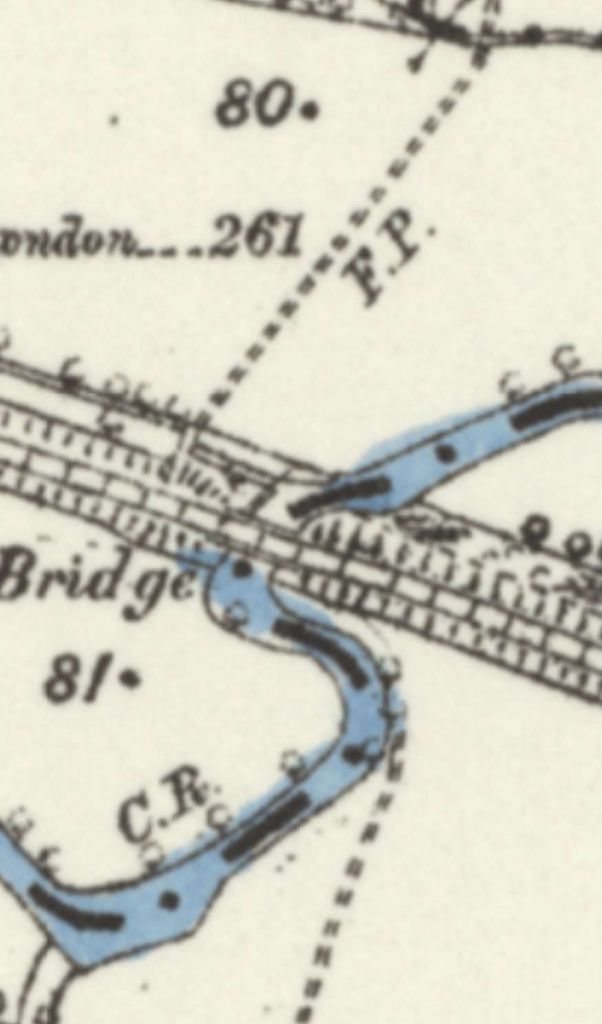

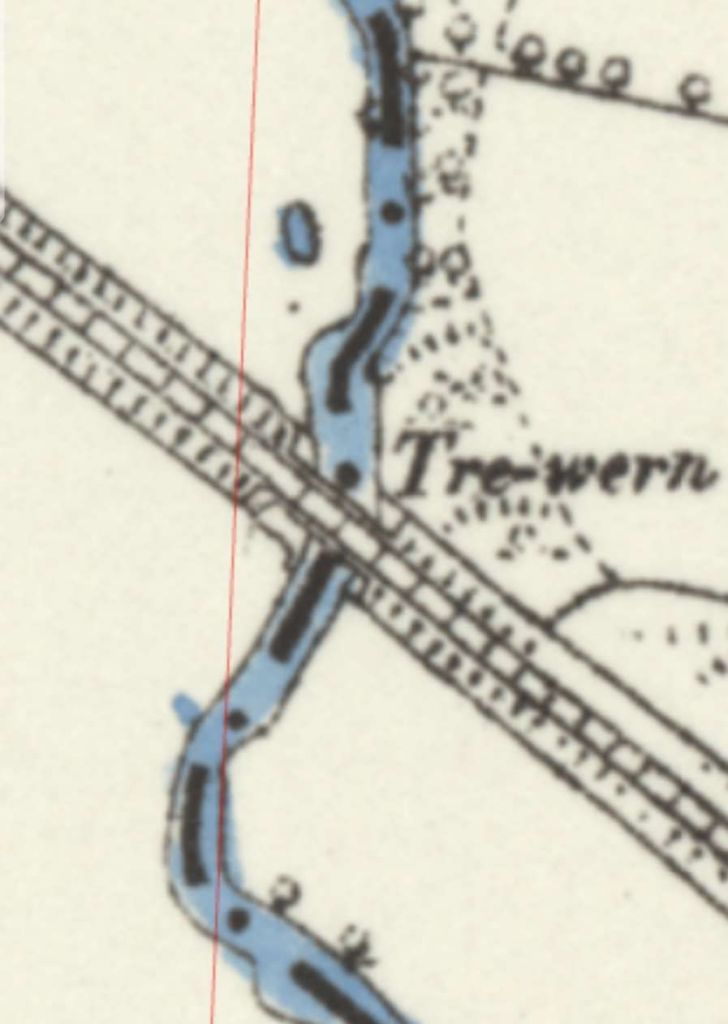

The first significant location South of Llanglydwen is the Dol-Wilym bridge over the Afon Taf. This appears at the top of the OS Map extract above and is shown below.

Connop Price says that between Llanglydwen and Login “the gradients continued to change often as the track followed the lie of the land; the steepest grade on this section was 1 in 40. About half a mile north of Login was the tightest curve on the railway: it was short but built to a mere 8 chains radius.” [4: p68]

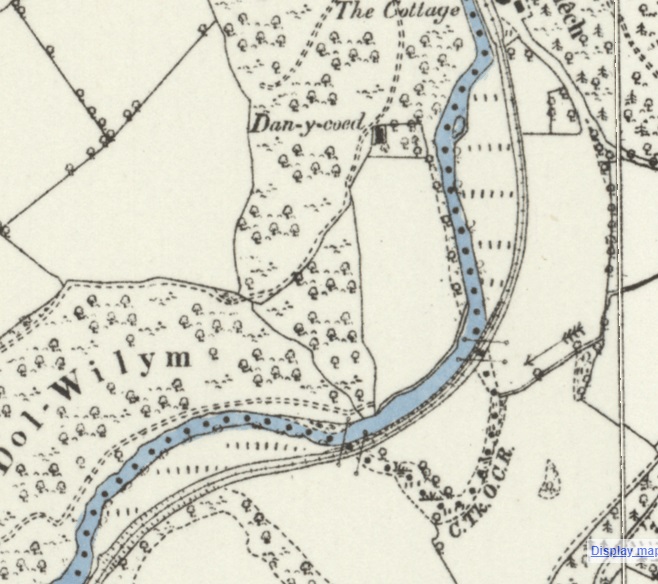

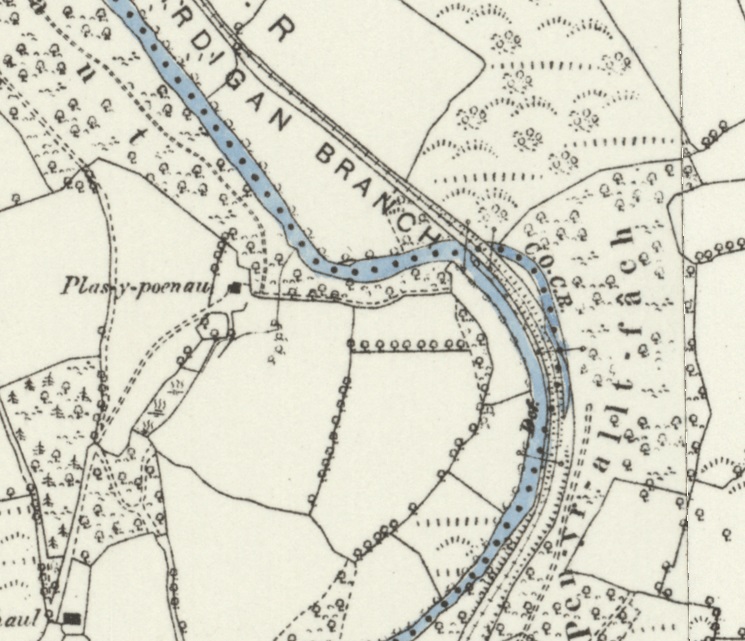

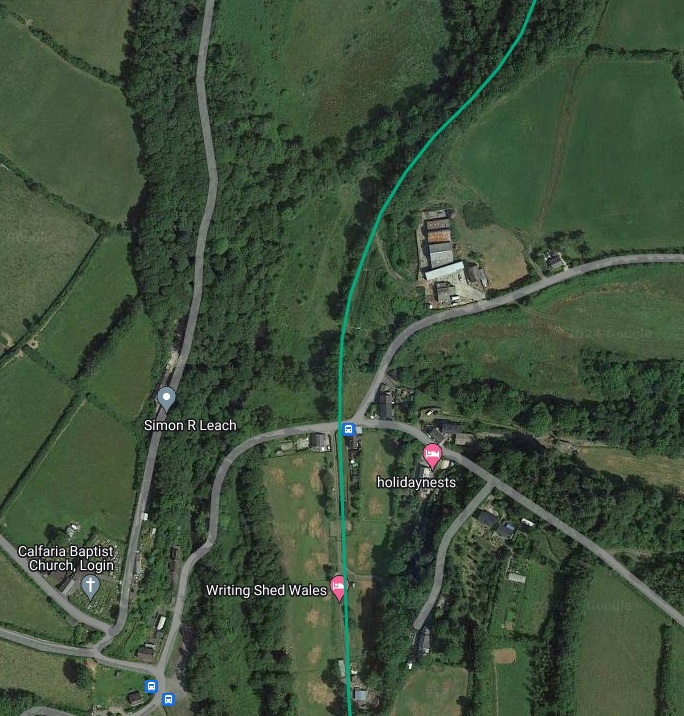

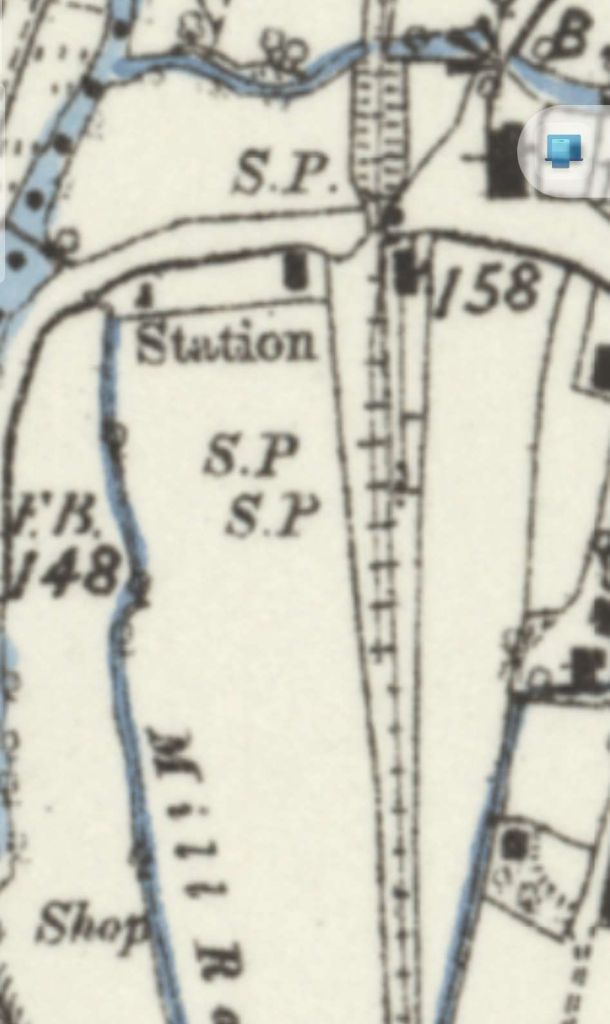

At Login, “a short platform was dignified by the large station building serving the tiny hamlet perched on the hillside just across the river. The goods loop was protected by a ground frame at each end, that at the south end being just a single lever unlocked by the Cardigan Junction – Llanglydwen electric tablet. The ground frame at the north end, however, also controlled the level crossing, and it was housed in a wooden hut of typical Great Western design.” [4: p68]

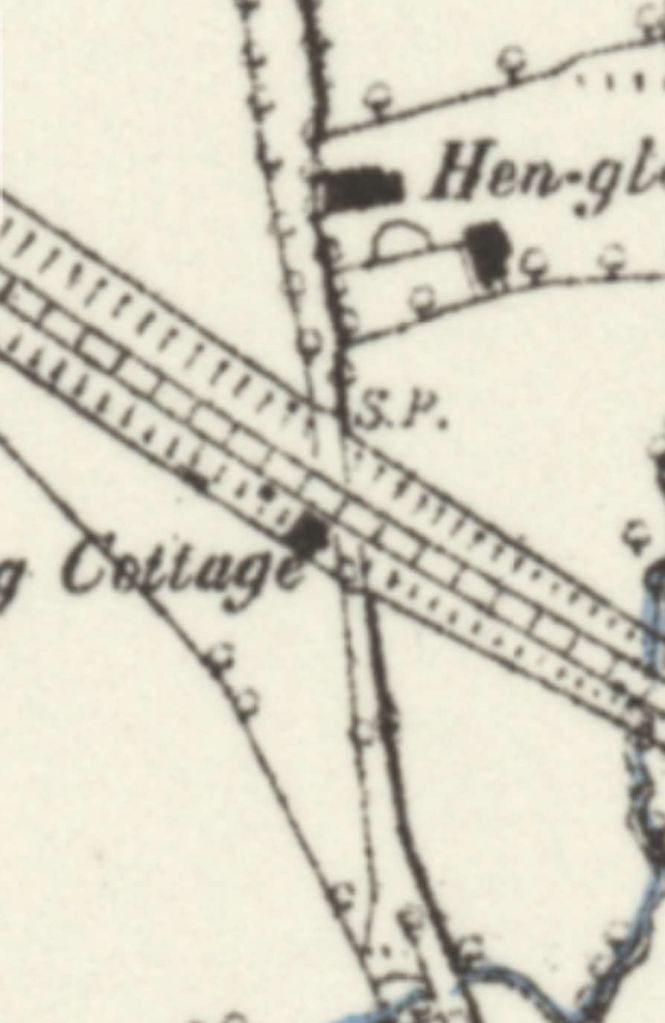

South of Login the valley of the Taf begins to widen out and the hillsides become less steep. However, gradients continued to change. On the East of the Taf, the railway ran through Penclippen level crossing and past its wooden crossing keeper’s hut.

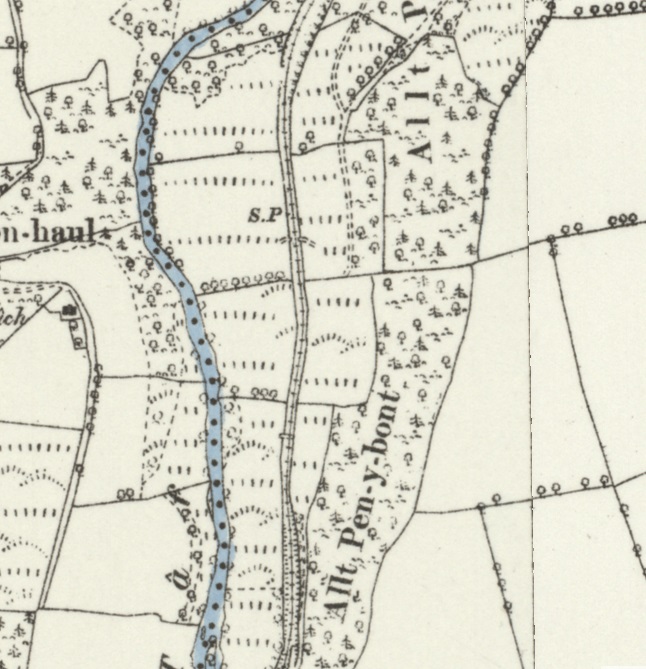

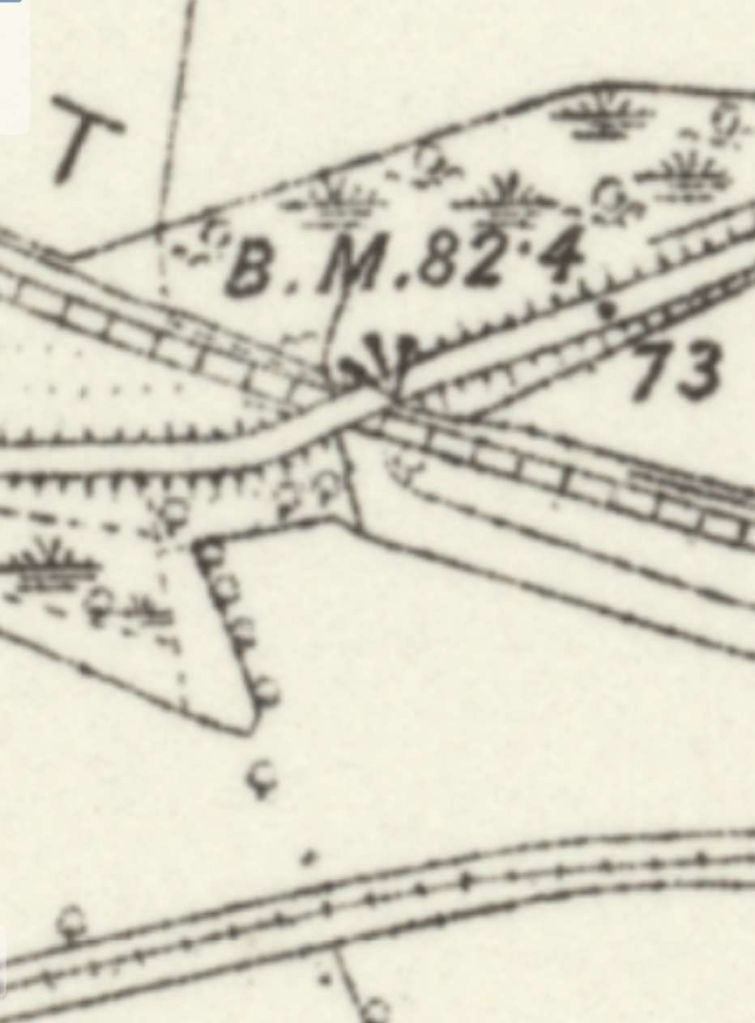

The Whitland & Cardigan Railway continued South to Llanfalteg (3 miles 48 chains from Whitland). “In the early years of the line … this place had some importance. Until the reconstruction of the mid-1880s the layout consisted of a loop, with a siding parallel to it to serve the goods shed, and a further siding for the locomotive shed and for coal traffic. In its heyday, the locomotive shed had a forge for day-to-day repairs, but it was not big enough to be able to undertake major overhauls. After the Great Western took over the W&CR the shed at Whitland assumed most of the responsibilities of Llanfallteg shed, and gradually the latter fell into disuse. For a while it was occupied by Mr J. Williams’ carpenter’s shop, but this ceased and decay set in until eventually the shed fell down in about 1939.” [4: p68]

“At closure in 1962, the station building and the wooden ground frame box were intact, and a dilapidated iron goods shed still stood by the level crossing. The layout, however, was reduced: the loop had been replaced by a siding, and although the siding to the goods shed remained the rest of the trackwork had long gone. A length of rusting cable in the undergrowth provided the only evidence of the practice at Llanfallteg of cable-shunting. The site was cramped and inconvenient, and for many years the most effective way of moving wagons in and out of the sidings was by a cable linking them to a locomotive on a parallel track.”

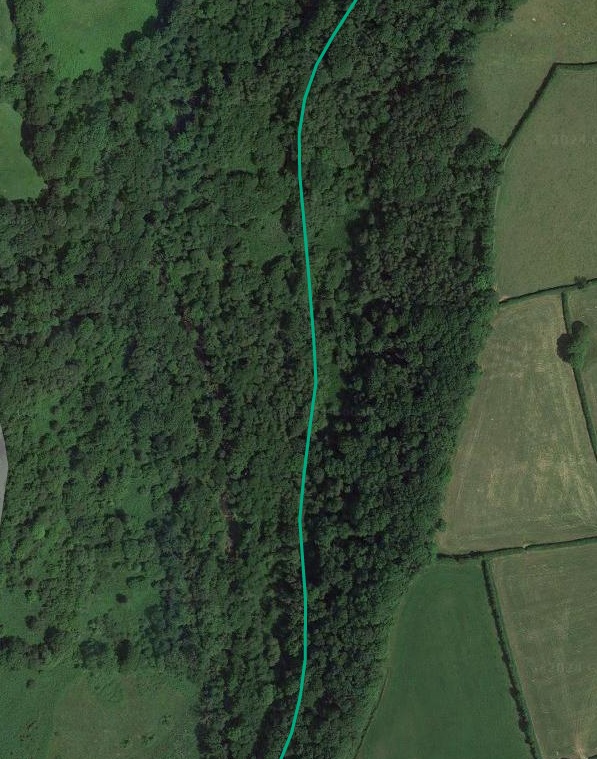

South of Llanfallteg a run of just over a mile brought the single track line to its junction with the main line known latterly as Cardigan Junction. There were no significant features on this length of the line. It remained on the Northeast bank of the Afon Taf.

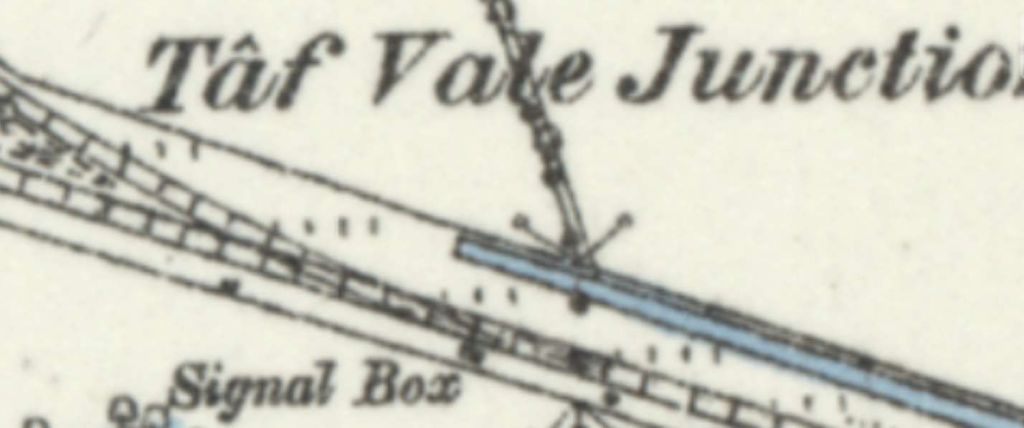

“At Cardigan Junction the signal box, opening in 1873 and closed in 1964, was whitewashed, pebble-dashed and austerely domestic in appearance, being built entirely in stone or brick. The window overlooking the tracks was a modest rectangle with two uprights in the window frame. The name-board ‘Cardigan Junction’ was located directly under it. The door was on the east side of the box, with another window, and the pitched roof was surmounted by a single chimney. A gaslight was situated outside.” [4: p68]

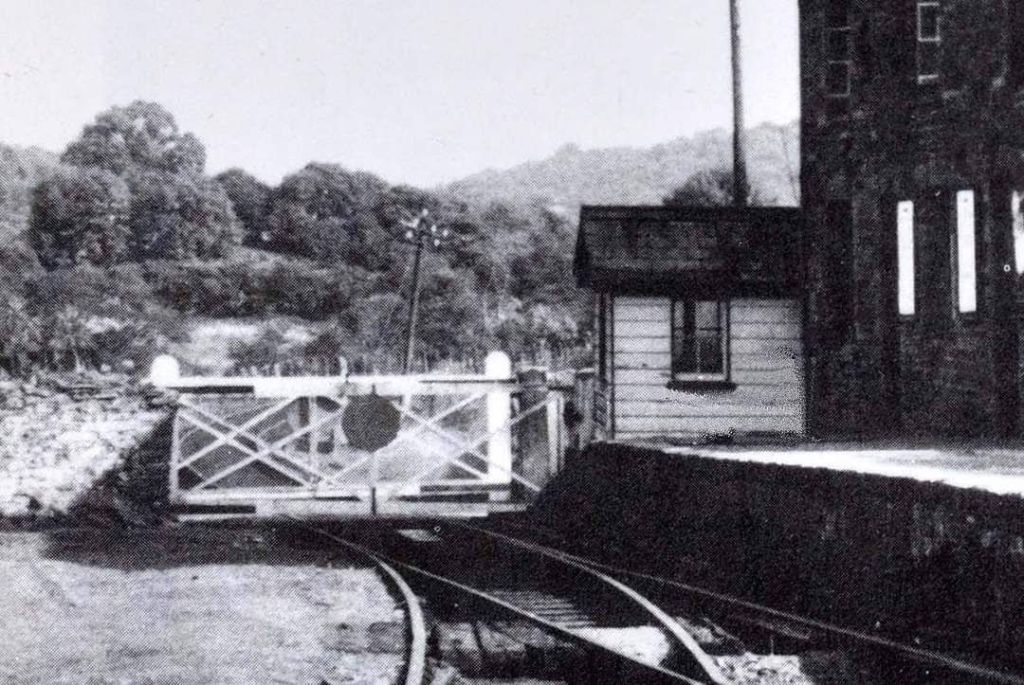

This photograph was taken on Saturday 25th May 1963, significant because the goods only rail service on the branch was withdrawn on the following Monday (27th May 1963). This picture was shared on the Login Railway Station Facebook Page on 20th June 2024. It looks Southeast. [8]

The last 2 miles 21 chains of the route was along the main line from Cardigan Junction (originally Taf Vale Junction) to Whitland.

There were no further significant features on the line before it entered Whitland Station.

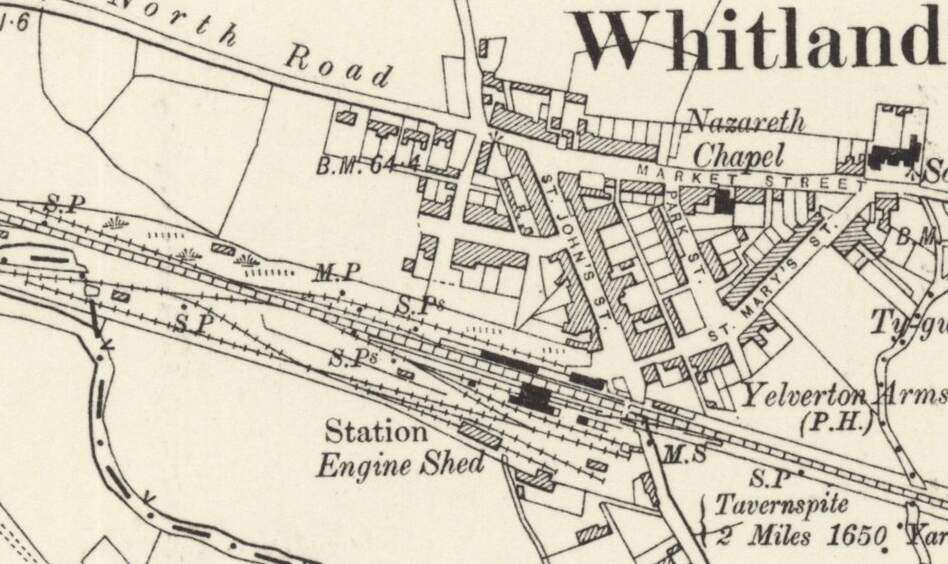

“After the opening of the Pembroke and Tenby and Whitland and Taf Vale Railways the station at Whitland had four platform faces. Two of these served the main line, one served a loop round the down island platform and the other a bay behind the up platform, access to which was from the west. The main station buildings were on the up side and nearby, close to the bay platform, there was a goods shed and a few sidings. All these changed little until British Railways’ days when the station was extensively modernised. In addition, in the 1960s the down loop was disconnected and became a bay for Pembroke Dock trains. On the down side, too, there was a small goods vard originally constructed for the use of the Pembroke and Tenby Railway, and for the exchange of traffic between that company and the GWR before the Great Western took over the working of the P&T in 1896. A short distance west of Whitland station the locomotive shed stood until the mid-1960s. Passenger trains from Cardigan ran into either the bay or the up main platform at Whitland, but trains departing for Cardigan customarily shared the outer face of the down island platform with P&T line trains.” [4: p61]

References

- https://preservedbritishsteamlocomotives.com/fox-walker-company, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- M.R. Connop Price; Before the Railways: The Early Steamers of Cardiganshire; in the RCHS Journal, Vol. 40 Part 8 No. 244 July 2022, p471-477.

- https://railmaponline.com/UKIEMap.php, accessed in July/August 2024.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/07/15/railways-in-west-wales-part-2a-the-whitland-cardigan-railway-cardigan-to-boncath.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/07/25/railways-in-west-wales-part-2b-the-whitland-cardigan-railway-boncath-to-llanglydwen

- M.R. Connop Price; The Whitland and Cardigan Railway (2nd Edition); The Oakwood Press, Headington, Oxford, 1991.

- C.J. Gammell; Slow Train to Cardigan; in British Railways Illustrated Volume 4 No. 5, February 1995, p228-235.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/wkGZo8ow7QjquYvi, accessed on 25th July 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/7G6PpWSruh98EJQv, accessed on 25th July 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Kent_Light_Railway, accessed on 26th July 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Peckett_and_Sons_railway_locomotives, accessed on 26th July 2024.

- https://www.rmweb.co.uk/forums/topic/72460-gwr-1331-ex-whitland-cardigan-0-6-0st-project, accessed on 26th July 2024.

- https://x.com/JonSLatona/status/1555748042376110080?t=MGZm0QpCXQztdDO4aIYn0A&s=19, accessed on 26th July 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/DtzcxUKZy6rBUUu3, accessed on 26th July 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3756804, accessed on 26th July 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/PbPSgvwUcgQw56dX, accessed on 26th July 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Llanglydwen_railway_station, accessed on 26th July 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.5&lat=51.90951&lon=-4.64625&layers=257&b=1&o=100, accessed on 24th July 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.6&lat=51.87913&lon=-4.66484&layers=257&b=1&o=100, accessed on 26th July 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/YThEDvmbTYJhb57u, accessed on 8th August 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4721738, accessed on 27th July 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1703219, accessed on 28th July 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.90756&lon=-4.64998&layers=257&b=1&o=100, accessed on 30th July 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.90419&lon=-4.65760&layers=257&b=1&o=100, accessed on 30th July 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.90071&lon=-4.66139&layers=257&b=1&o=100, accessed on 30th July 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.89728&lon=-4.66253&layers=257&b=1&o=100, accessed on 30th July 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.89362&lon=-4.66594&layers=257&b=1&o=100, accessed on 30th July 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.88936&lon=-4.66134&layers=257&b=1&o=100, accessed on 30th July 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.88511&lon=-4.66114&layers=257&b=1&o=100, accessed on 30th July 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.88100&lon=-4.66301&layers=257&b=1&o=100, accessed on 30th July 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/GHTPSQBAfQ4YCMNL, accessed on 9th August 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/7Rns5L1LJ8iCKFFf, accessed on 9th August 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/jRJQhnqenneHQXX3, accessed on 9th August 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/z1CyZqboS8yjc6zv, accessed on 9th August 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/7309799, accessed on 9th August 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/6gDMXW2YBFgNqmj9, accessed on 9th August.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.0&lat=51.84779&lon=-4.67887&layers=6&b=1&o=100, accessed on 9th September 2024.

- http://www.llanfallteg.org/information/photographs, accessed on 9th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=51.83427&lon=-4.66215&layers=6&b=1&o=100, accessed on 9th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=51.83245&lon=-4.65458&layers=6&b=1&o=100, accessed on 9th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=51.82813&lon=-4.64390&layers=6&b=1&o=100, accessed on 9th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=51.82198&lon=-4.63287&layers=6&b=1&o=100, accessed on 9th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.81995&lon=-4.62494&layers=6&b=1&o=100, accessed on 9th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.81879&lon=-4.61463&layers=6&b=1&o=100, accessed on 9th September 2024.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Whitland_railway_station,_Wales_in_1971.jpg, accessed on 9th September 2024.

- http://disused-stations.org.uk/w/whitland/index.shtml, accessed on 9th September 2024.

- https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/410170, accessed on 9th September 2024.