Another article from The Railway Magazine in May 1951! This time we are in Ireland, specifically in County Clare.

The May 1951 edition of the magazine carried an article on the 3ft gauge light railway which ran from Ennis to Kilrush and Kilkee. The total length of the railway was about 53 miles. [1]

The Railway Magazine article only touched the surface of the story of the line. This post seeks to pull together available information and provide a survey of the line.

Edmund Lenihan, in his book, “In the Tracks of the West Clare Railway,” says: “Merely to get the first train moving took almost four decades and labyrinthine proposals, counter-proposals, false starts, politicking, bankruptcy and natural disaster. It certainly reads like a saga, and, for good measure, it was largely a family affair between the people of Clare, Catholic and Protestant, landlord and peasant, priest and layman, town and country, with a few important outsiders thrown in to lend spice to the mixture.” [8]

Many attempts were made to provide railway transport connections to West Clare but the area was just too remote for investors to take the risk of spending their money on such ventures. They could not imagine there being enough freight or people for a railway to make a profit. Then, in answer to exactly this problem in such areas of Ireland, Parliament passed an Act called “The Tramways Act” in 1883 the provisions of which included clauses to permit a narrow gauge track (thereby more than halving the building costs) and giving guaranteed returns to the investors. [5]

The 43.4 km (27 mi) West Clare Railway between Ennis and Miltown Malbay was built a few years’ earlier than the South Clare Railway. The first sod was cut on 26 January 1885 at Miltown Malbay by Charles Stewart Parnell, M.P., although actual work on the line had begun in November 1884. [4]

Although some of the list below feels like we are getting ahead of ourselves, Edmund Lenihan provides a list of the major stages in the development and life of the West Clare railway: [8]

- 1845: First KiIkee—Kilrush/Cappagh rail link propose(‘ by Col. Vandeleur.

- 1858: First scheme to reach the stage where ground was actually broken to lay a railway in west Clare.

- 31st July 1871: Ennis and West Clare Railway receives Act of Incorporation and is authorised to build a narrow-gauge line (the first company in Ireland to get such permission).

- 24th August 1883: Tramways Act passed by Parliament.

- 15th December 1883: West Clare Railway Company registered.

- 9th June 1884: South Clare Railway Company formed.

- 26th January 1885: First sod of West Clare Railway turned by Parnell at Miltown Malbay.

- 2nd July 1887: West Clare Railway opened for regular services.

- 9th October 1890: First sod of South Clare Railway turned by Mrs Reeves at Kilkee.

- 23rd December 1892: South Clare Railway opened for regular services.

- 1st January 1925: Amalgamation of West Clare Railway and Great Southern Railways.

- July 1927: ETS signalling introduced on Ennis-Miltown sections of the West Clare line.

- 1945: CIE takes over the West Clare line.

- 1948: Milne Report. First official mention of possible closure of West Clare branch of CIE.

- 1952-55: Dieselisation.

- 31st January 1961: Closure of West Clare line.

Back again to the story! The section in italics below comes from ‘In the Tracks of the West Clare Railway’ by Edmund Lenihan. [8][9]

After the Famine, railway fever gripped Ireland just as it did the rest of Great Britain at the time. In the period 1845 to 1885 at least a dozen schemes were proposed for railways in Co. Clare alone.

“The large population of the time may have justified such proposals, but much of the impetus certainly came from landlords whose travels abroad demonstrated to them the advantage of fast and comfortable transport, and emphasised the shortcomings of their own home areas. [10] …... All these plans were similar in some vital respects: they all included as their terminus points Ennis, Kilrush and Kilkee. At that time traffic on the Shannon was considerable, and Cappagh pier had to figure large in any route that hoped to be profitable, but how Cappagh might be made accessible was the subject of widely varying proposals. …. The various plans formulated in the 1840s and 1850s foundered on one common rock: finance, and this largely because they proposed crossing Poulnasherry Bay rather than going round it. Certain progress was made in each of these early schemes but all failed to reach the construction phase.” ….. [8][12]

The failure of the most promising of the schemes led to a twenty year hiatus before another scheme reached construction. In that twenty years there were

“very many meetings and proposals, both for the Kilrush—Kilkee section and for the Ennis—Miltown route, including, in 1871, one for a line from Ennis to Miltown via Corofin, Ennistymon and Lahinch — exactly the route later taken by the West Clare Railway. But practical developments had to await the passing of the Tramways Act in August of 1883, a measure that allowed the interest on capital to be guaranteed by the baronies through which a railway passed.” [8][13]

The directors appointed W.M. Murphy [8] as contractor to build the railway. (Murphy was later to become a major newspaper owner and caused the infamous worker’s lockout in Dublin in the early years of the 20th century.) [5]

Early in 1887 locomotives nos. 1 and 2 arrived, and no.3, Clifden and no. 4, Besborough, had been completed by their builder, W.G. Bagnall of Stafford, and all seemed fair for the completion of work in a short time. [8][14] In fact, various legal and other obstacles had to be overcome and the line only opened on 2nd July 1887. [4]

Whilst the West Clare was being built, a number of the directors who owned lands in the far west of the county decided to form a second company to promote a similar railway serving the towns of Kilrush and Kilkee. These towns had always been the targets for the original railway plans. However, no agreement could be found as to the direction of the railway with many believing that the line could be built across the tidal Poulnasherry Bay with the resulting land reclamation providing rental incomes which would largely defray the costs of building the line. However desirable the plan looked in theory, it was not until Murphy explained that he could not calculate the costs of making the line sea-resistant and could not guarantee the results anyway that the directors finally decided that the South Clare Railway should go to Moyasta where the necessary division of the line would take place and a line built to connect with the West Clare Railway at Miltown Malbay. [5]

Although the South Clare was formed as a Company in June 1884, it was not until 6 years later in 1890 that work started on the extension. [15] The South Clare Railway built the extension from Miltown Malbay to Kilrush, Cappagh Pier (Kilrush Pier) and Kilrush docks with a branch to Kilkee from Moyasta, with work starting on the extension in October 1890 and opening on 11 May 1892. [4] There appears, however, still to have been work to complete after the opening, as one source suggests that the South Clare was not completed until December 1892. [5] The extension was worked by the West Clare Railway and was initially dogged by poor service and time keeping, but this later improved. [4]

“The two companies worked closely together from the very start and many of the officers were common to both. Such was George Hopkins, appointed to design and supervise the rolling stock. Hopkins came to give Dubs & Co of Glasgow a specification for three locomotives the detailed design of which would be left to Dubs. The first of these was Number 5 named “Slieve Callan” which arrived in March 1892. These locomotives were designed to pull the expected loads at the timetabled speed of 25 mph over gradients as fierce as 1 in 50 along a track of 48 miles in length. They were therefore large and powerful engines built to the limits of the permitted loading gauge.” [5]

“The railway timetable for three trains each way between Ennis and Kilkee with branch line connections to Kilrush was published under the sole name of the West Clare Railway in June 1893. From then on, the railway trundled on gaining new passengers as its services became better known. It is, for example, no accident that the Lahinch golf course was laid out at this time – British Army officers could use the railway to travel to the course easily. The Lisdoonvarna Festival each September gained a new lease of life as passengers could get as near as Ennistymon from all parts of Ireland. The Burren cattle trade was enhanced by the ease of transporting the cattle away from the market. The Kilrush Horse Fair and the Lahinch Garland Day celebrations took on a new significance. Kilkee, always a popular resort, became known as the “Brighton of the West” whilst new goods and services were brought to the shops by travelling salesmen, postal services quickened by degrees and newspapers from Dublin became available on the day. By the turn of the century, the timetable was showing 5 trains each way. More than 200.000 passengers travelled the line and 80.000 tonnes of freight and livestock were carried each year with 2/3rds of the passengers travelling during the summer months.” [5]

On 1st January 1925, the rolling stock and locomotives became the property of the Great Southern Railways (GSR). Efforts were made from time to time to modernise the system, and to make it safer and more cost-effective — for example, by the introduction of ETS working in July 1927 and the purchase of two Drewry railcars in 1928. [15][20]

With control being exercised from Dublin inefficiency was no longer tolerated and local sentiment was of much less significance. “A large part of the Ennis carriage-building works and maintenance depot was closed down, and ballast ceased to be quarried locally, all supplies now coming from the GSR quarry at Newbridge, Co. Kildare. [21] The only link with tradition preserved in this regard was that the 1908 decision of the West Clare Company to ballast the line annually in May, June and October was adhered to until the time of the closure of the system in 1961. A proposal was made in 1936 to widen the gauge from 3 feet to the standard 5-foot-3-inches so as to avoid the necessity for transfer of all goods at Ennis Station, but this came to nothing in spite of a lively debate on the matter in the local press which lasted well into the 1940s. The cost would have been out of all proportion to any prospective benefits.” [15]

In subsequent years steam passenger services were replaced by railcars but the financial position did not significantly improve and closure became more and more likely. “And so it was that on 27th September 1960 the death sentence was pronounced: it was declared publicly that the line would close on 31st January 1961.” [16] The line closed on that date.

The Route of the West Clare Railway

We start our survey of the line from the station In Ennis where the West Clare Railway connected with the national railway network. The adjacent image shows the station looking to the South. [4]

We start our survey of the line from the station In Ennis where the West Clare Railway connected with the national railway network. The adjacent image shows the station looking to the South. [4]

The following image shows the view North from the station platform. Ennis railway station in September 1950, with the West Clare Railway carriage in the foreground. The carriage works are in the rear to the left, the engine shed in the centre and the two span Quin Road bridge to the rear right. [2]

Ennis railway station in September 1950, with the West Clare Railway carriage in the foreground. The carriage works are in the rear to the left, the engine shed in the centre and the two span Quin Road bridge to the rear right. [2] The same set of carriages, this time looking south towards the station buildings. Both pictures were taken in 1950, (c) O’Dea Photograph Collection via http://www.nli.ie. [2]

The same set of carriages, this time looking south towards the station buildings. Both pictures were taken in 1950, (c) O’Dea Photograph Collection via http://www.nli.ie. [2] The West Clare platform at Ennis Station, date unknown.

The West Clare platform at Ennis Station, date unknown. Ennis Station in 1952, (c) IRRS. This picture and that below were taken from approximately the same position but 10 years apart. Just visible on the right-hand side of the picture is the West Clare Engine Shed. In the immediate vicinity of the engine shed were a turntable and carriage works. [16]

Ennis Station in 1952, (c) IRRS. This picture and that below were taken from approximately the same position but 10 years apart. Just visible on the right-hand side of the picture is the West Clare Engine Shed. In the immediate vicinity of the engine shed were a turntable and carriage works. [16] Ennis Station in 1962, just a short time after the closure of the West Clare Railway. No trace remains! [6]

Ennis Station in 1962, just a short time after the closure of the West Clare Railway. No trace remains! [6] The same location in June 2006, (c) Francoise Poncelet. [3]

The same location in June 2006, (c) Francoise Poncelet. [3]

Ennis Station in June 2017 is shown above looking from the North, Google Streetview. The adjacent satellite image shows the station in 2017 with Quin Road to the north passing over the railway.

Ennis Station in June 2017 is shown above looking from the North, Google Streetview. The adjacent satellite image shows the station in 2017 with Quin Road to the north passing over the railway.

Ennis Railway Station is today the terminus station of the Limerick to Ennis Commuter service and a station on the Limerick to Galway intercity service. Passengers for Dublin/Cork or Waterford transfer at Limerick. The station forms part of the Western Railway Corridor, the name given to a group of lines in the west of Ireland between Limerick and Sligo. Five services pass through Ennis on the Limerick–Galway service with more just running Limerick–Ennis. [7]

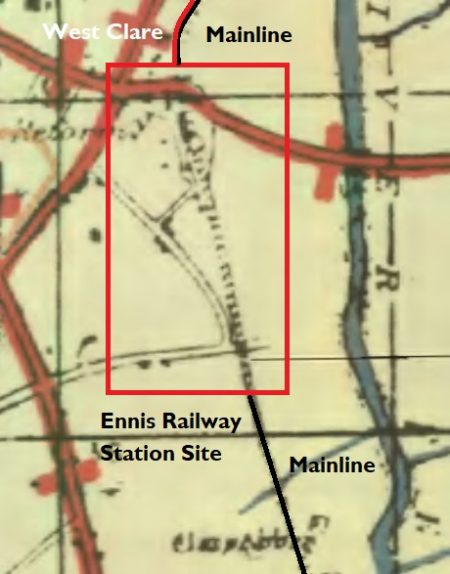

In the past it was also the terminus of the 3ft-gauge West Claire Railway which ran North from the station alongside the mainline. North of Quin Road the land is shown on the adjacent 1917 OS Map as being used by a rail-served sawmill.

In the past it was also the terminus of the 3ft-gauge West Claire Railway which ran North from the station alongside the mainline. North of Quin Road the land is shown on the adjacent 1917 OS Map as being used by a rail-served sawmill.

South of Quin Road, the grass triangle on the satellite image above provided facilities for the West Clare Railway. These included a carriage-works a turntable and an engine shed. A platform extended under the Quin Road bridge and a water tank could be found on the North side of the abutments of the bridge.

It is interesting to note that the Sawmill was rail-served by both railways with the broad-gauge having a siding crossing the 3ft-gauge lines.

The facilities shown to the South of the station buildings were those for the main-line. [29]

The adjacent map is the best excerpt that I could find from the GSGS 1-inch map from around 1940. [17]

The map below that is an extract from the Bartholomew quarter-inch map from 1940. Which shown Ennis station and the 3ft-gauge West Clare line leaving the mainline to the North. [18]

The picture immediately below these maps shows the line of the West Clare which ran on the West side of the mainline. The West Clare is long-gone by the time this picture was taken and the mainline track layout has been streamlined

The following monochrome picture looks back through Quin Road Bridge to Ennis Station and shows the two 3ft-gauge lines passing under the bridge.

Two lines of the West Clare Railway originally passed under Quin Road Bridge and served engine shops, a goods shed, loading bays and a transfer bank with a 3-ton crane all in a compound on the North side of the bridge. [16]

Two lines of the West Clare Railway originally passed under Quin Road Bridge and served engine shops, a goods shed, loading bays and a transfer bank with a 3-ton crane all in a compound on the North side of the bridge. [16] A diesel railcar about to leave Ennis Station on 25th July 1954, (c) IRRS. The West Clare had its own bridge span under Quin Road. That span has now been blocked off. [16]

A diesel railcar about to leave Ennis Station on 25th July 1954, (c) IRRS. The West Clare had its own bridge span under Quin Road. That span has now been blocked off. [16] This general view of Ennis Station was taken in May 1950 by P.B. Whitehouse. The 3ft-gauge Engine Shed can just be seen on the very right of the picture. [30]

This general view of Ennis Station was taken in May 1950 by P.B. Whitehouse. The 3ft-gauge Engine Shed can just be seen on the very right of the picture. [30] Loco No. 6C is shunting in front of what is marked on the OS plan as a sawmill at Ennis. Taylor records that building as being a transshipment shed. The year is 1954 or 1955. The broad-gauge siding can be seen crossing the 3ft-gauge to access the shed. Taylor also talks of a loco-repair works being to the right of the transshipment shed, (c) L. Hyland. [31]

Loco No. 6C is shunting in front of what is marked on the OS plan as a sawmill at Ennis. Taylor records that building as being a transshipment shed. The year is 1954 or 1955. The broad-gauge siding can be seen crossing the 3ft-gauge to access the shed. Taylor also talks of a loco-repair works being to the right of the transshipment shed, (c) L. Hyland. [31] Loco No. 3C is taking on water in the above image. This is an image from the early 1930s and the loco was less than 10 years old at the time, (c) A.W. Croughton. [31]

Loco No. 3C is taking on water in the above image. This is an image from the early 1930s and the loco was less than 10 years old at the time, (c) A.W. Croughton. [31] A ‘Walker’ of Wigan railcar travels north from Ennis Station on the West Clare, alongside is the Irish standard gauge line. [27]

A ‘Walker’ of Wigan railcar travels north from Ennis Station on the West Clare, alongside is the Irish standard gauge line. [27] This monochrome image shows the two railway lines running parallel across the twin bridges over the River Fergus at Clonroad, around a mile North of Ennis Station, in 1953. The picture is taken looking back towards Ennis. (c) IRRS

This monochrome image shows the two railway lines running parallel across the twin bridges over the River Fergus at Clonroad, around a mile North of Ennis Station, in 1953. The picture is taken looking back towards Ennis. (c) IRRS This map is another extract from the GSGS 1-inch map from around 1940. It shows the West Clare line leaving the mainline just to the North of the modern R352 Tulla Road which is then pictured in Google Streetview image which follows. The bridge over the Tulla Road is shown in 2017 and clearly shows a modern reinforced concrete deck spanning masonry abutments. [17]

This map is another extract from the GSGS 1-inch map from around 1940. It shows the West Clare line leaving the mainline just to the North of the modern R352 Tulla Road which is then pictured in Google Streetview image which follows. The bridge over the Tulla Road is shown in 2017 and clearly shows a modern reinforced concrete deck spanning masonry abutments. [17] Tulla Road Railway Bridge from the West. The West Clare crossed this bridge on the near side of the mainline railway.

Tulla Road Railway Bridge from the West. The West Clare crossed this bridge on the near side of the mainline railway.

Over a distance of about 300 yards north of the Tulla Road the two lines curved gently to the right taking a more northerly path. As they did so they crossed a small stream on a fine stone-arched bridge. One hundred yards further on, at Corrovorrin level crossing, the old road to Ballycoree crossed the two railways. The road is now very much a minor road but was once one of the main roads out of Ennis. [19]

Over a distance of about 300 yards north of the Tulla Road the two lines curved gently to the right taking a more northerly path. As they did so they crossed a small stream on a fine stone-arched bridge. One hundred yards further on, at Corrovorrin level crossing, the old road to Ballycoree crossed the two railways. The road is now very much a minor road but was once one of the main roads out of Ennis. [19]

Just beyond this crossing the West Clare Railway diverged from the mainline. Its route is shown approximately by the red line on the satellite image above. The line curved around to travel almost due East before crossing Shaughnessy’s bridge just a stone’s throw from the boundary wall of Our Lady’s Hospital. The curving line through what is now the hosuing estate was known as Tank Curve after the huge hospital water tank.

The line curved around to travel almost due East before crossing Shaughnessy’s bridge just a stone’s throw from the boundary wall of Our Lady’s Hospital. The curving line through what is now the hosuing estate was known as Tank Curve after the huge hospital water tank. The West Clare continued in a westerly direction crossing the R458 Gort Road. The old road can be seen on the left of the above satellite image joining the alignment of the modern road at the top of the picture. The line continues West towards the River Fergus as shown below.

The West Clare continued in a westerly direction crossing the R458 Gort Road. The old road can be seen on the left of the above satellite image joining the alignment of the modern road at the top of the picture. The line continues West towards the River Fergus as shown below.

The West Clare crossed the River Fergus on the ‘Lifford Bridge’ as it was called in the Clare Saturday Record report of 20th August 1887, which described an attempt to blow up the bridge that week. Edmund Lenihan comments: “The job was bungled, however, and the bridge still survives, though somewhat the worse for wear. All that remains is the skeleton of girders which once supported the metal deck, and these have not weathered the years well since their laying down in 1886. They are seriously corroded at many points and gave us several heart-stopping moments as we picked our way carefully across. Testing our luck and our balance, we hopped from girder to rotten girder, while under us the Fergus flowed fast and deep. No person in his sane senses would wish to fall in here, but the children of the town often thought otherwise, for on hot summer afternoons the more daredevil among them, bent on mischief, would climb onto the last carriage as the train pulled slowly away from Lifford Halt, ready themselves as it approached this bridge, and then jump off into the river as it crossed.” [19]

The West Clare crossed the River Fergus on the ‘Lifford Bridge’ as it was called in the Clare Saturday Record report of 20th August 1887, which described an attempt to blow up the bridge that week. Edmund Lenihan comments: “The job was bungled, however, and the bridge still survives, though somewhat the worse for wear. All that remains is the skeleton of girders which once supported the metal deck, and these have not weathered the years well since their laying down in 1886. They are seriously corroded at many points and gave us several heart-stopping moments as we picked our way carefully across. Testing our luck and our balance, we hopped from girder to rotten girder, while under us the Fergus flowed fast and deep. No person in his sane senses would wish to fall in here, but the children of the town often thought otherwise, for on hot summer afternoons the more daredevil among them, bent on mischief, would climb onto the last carriage as the train pulled slowly away from Lifford Halt, ready themselves as it approached this bridge, and then jump off into the river as it crossed.” [19] A few hundred yards further along the old line it crossed Drumcliffe Road on a low girder bridge. The abutments still remain (above). The line then continues to curve round from west to North and crosses a narrow point on Lough Cleggan (on the satellite image below).

A few hundred yards further along the old line it crossed Drumcliffe Road on a low girder bridge. The abutments still remain (above). The line then continues to curve round from west to North and crosses a narrow point on Lough Cleggan (on the satellite image below).

We arrive next at a level crossing, the first since Lifford Halt – Erinagh Crossing, in the townland of Reascaun, 3.5 miles from Ennis. The picture above shows the railway formation arriving at the Crossing.

The adjacent satellite image shows that crossing at the bottom of the extract from Google Earth.

The adjoining house no longer looks like a crossing cottage. It has been too much modernised and altered to be recognisable as such. [22]

The picture below shows the bungalow that was once the crossing-keeper’s cottage. North of the extended cottage the line crossed open fields and then, on an embankment, a boggy marsh which is evident at the top of the adjacent image and at the bottom of the satellite image below. North of the marshland the route of the line has been re-landscaped and is very indistinct on the ground and on satellite images. [22]

North of the marshland the West Clare crossed the road running Northeast from Ballygriffey at grade right next to Ballygriffey Castle and on the West side of the small stream which it had crossed on a bridge a couple of hundred yards short of the road crossing.

North of the marshland the West Clare crossed the road running Northeast from Ballygriffey at grade right next to Ballygriffey Castle and on the West side of the small stream which it had crossed on a bridge a couple of hundred yards short of the road crossing.

The monochrome image below shows Ballygriffey Castle and the minor road crossing close by.

As a gated crossing there was a crossing keeper and cottage. Once again the cottage has been so reconstructed that none of its railway features remain.

The crossing, 4.75 miles from Ennis, and we are now entering the 7-mile length to Willbrook that was once under the jurisdiction of Corofin Station. Ballygriffey Castle and railway crossing gates in 1953, (c) IRRS. [23]

Ballygriffey Castle and railway crossing gates in 1953, (c) IRRS. [23]

The extended crossing-keepers cottage is seen above from the Southwest in April 2009.

The extended crossing-keepers cottage is seen above from the Southwest in April 2009.

North of the cottage, a ballast siding was established in 1904 and a quarry opened alongside to supply the needs of the railway after the siding at Skagh Point near Kilrush was closed because of a dispute with the Crown over royalties. Edmund Lenihan comments: “One would be hard put now to say where the siding was, since not alone has it vanished, but the line, too. Yet if some of the survivors of the backbreaking slavery undergone here are to be believed, its obliteration is little loss to the world.To be consigned to ‘duty in Ballygriffey’ was akin to penal servitude, it seems, for even the gangers in command were more truculent here than else-where, as if the place exuded some baleful influence of its own.” [23]

The railway gradually turned towards the Northwest as shown on the adjacent satellite image running to the East of the hamlet of Ballygriffey North and then crossing another marshy area on embankment. The railway crossed open limestone grassland on its way towards Ballycullinan Lough. On the way it crossed three roads. The first of these was the site of Ruan Station and Level-Crossing. The third is now the R476 which itself is heading for the next village on the line, Corofin. [24]

The railway crossed open limestone grassland on its way towards Ballycullinan Lough. On the way it crossed three roads. The first of these was the site of Ruan Station and Level-Crossing. The third is now the R476 which itself is heading for the next village on the line, Corofin. [24] Ruan Crossing Gates and Crossing-keeper’s cottage in 1953. [25]

Ruan Crossing Gates and Crossing-keeper’s cottage in 1953. [25] A Google Earth image of Ruan Station in the early years of the 21st Century.

A Google Earth image of Ruan Station in the early years of the 21st Century. Looking back along the line towards Ennis in April 2009. The stone pilasters in the centre of the image are the pillars which held the crossing gates.

Looking back along the line towards Ennis in April 2009. The stone pilasters in the centre of the image are the pillars which held the crossing gates. Ruan Station Building. The picture is a Google Streetview image and was taken in April 2009.

Ruan Station Building. The picture is a Google Streetview image and was taken in April 2009.

Ruan station-house is, “resplendently restored and transformed into an elegant dwelling quite unlike the general run of modern country houses. From the boundary wall to the road, where the crossing gates once stood, the line is now a neat garden and lawn, but even more noticeable is the surrounding stonework, for much care has been taken to preserve it, especially the level-crossing piers. It is altogether a credit to its owner. Hard to believe, looking at it now, that this same building was sold by CIE in October 1962 for the princely sum of £15.” [25]

Properly speaking, this station should not have been called Ruan Station, since it is in the townland of Kilkee East, and the village of Ruan is a good 2.5 miles away. However, it would have been highly confusing, even on the West Clare, to have two destinations of the same name. So Ruan Station it had to be, and Kilkee remained the western terminus of the line.

“Ruan Station was first made a halt in 1888, but only after some rather novel persuasive tactics by the parish priest, Fr Garry. It seems that the railway company had no intention of providing even a halt at Ruan, let alone a station, so the priest (who is described as ‘a tall, powerful man and a forceful character’ who got his own way in most things) took to driving his pony and trap onto the line, forcing the train to stop. The company at last got the message; since it looked as though they would have to be constantly stopping anyway, they decided to make it official in 1888. Ten years later, however, it was closed, only to be reopened in 1904 — whether by Fr Garry’s efforts we do not know. That worthy man continued as parish priest in Ruan until 1912, and is buried there.” [25]

In 1921, the halt was closed again, and the platform removed. [25]

Heading on from Ruan, the line continued in a Northwesterly direction and met the modern D476. The crossing was at grade and at a very shallow angle as can be seen on the satellite image below.

For a short distance, the road and railway ran parallel to easch other in close proximity. The road then turned North to Corofin and the railway turned gradually to the West and on the way entered Corofin Station. [24]

For a short distance, the road and railway ran parallel to easch other in close proximity. The road then turned North to Corofin and the railway turned gradually to the West and on the way entered Corofin Station. [24]

Corofin Station in June 1961, just after closure earlier inn the year, (c) IRRS. [28] Google Streetview image of Corofin Station buildings in 2009.

Google Streetview image of Corofin Station buildings in 2009. Corofin Station in 2017. [26]

Corofin Station in 2017. [26]

We complete the first part of our journey along the West Clare Railway at Corofin.

References

- P.B. Whitehouse; The West Clare Railway; in The Railway Magazine Volume No. 601, May 1951, p296-298, p320, p345. (Articles from back copies of the magazine can be found online using a subscription service to The Railway Magazine archives.)

- http://clareherald.com/2014/09/old-images-of-clare-ennis-railway-station-1950, accessed on 6th April 2019.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ennis_Station_-_geograph.org.uk_-_296727.jpg, accessed on 6th April 2019.

- http://www.skibbereeneagle.ie/ireland/west-clare-railway, accessed on 6th April 2019.

- http://www.westclarerailway.ie/about/history, accessed on 6th April 2019.

- http://clareherald.com/2015/07/old-images-of-clare-ennis-railway-station-1962, acessed on 6th April 2019.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ennis_railway_station, accessed on 6th April 2019.

- Edmund Lenihan; In the Tracks of the West Clare Railway; Mercier Press, Dec. 2008, p16-19.

- Ignatius Murphy; The Kilrush-Kilkee Railway and Reclamation of Poulnasherry Bay; in The Other Clare, Volume 6, 1982, p16.

- Ibid, p17. But note also the Clare Journal of 26th March 1849, and 2nd April 1849, which berated the gentlemen of Clare for their lack oof interest in ensuring that the proposed branch line from Limerick to Galway should pass through the county, whereas their Gaway counterparts were suitably active in this matter.

- In July 1866 a case of traverse in the matter of Kilrush and Kilkee Railway Company came to court. A Mr. Shannon was claiming £600 compensation for land that was to be taken by the railway in Leaheen and Kilnagalliagh. The company was offering £200. See the Clare Journal,12th July 1866.

- Munster News; 29th May 1869 and 25th August 1883.

- Clare Saturday Record; 6th March 1886, and L. Hyland, Twilight of the West Clare, 1961, p1 (pamphlet distributed on the day the line closed).

- H. Fayle; Narrow Gauge Railways of Ireland; Greenlake Publications Ltd., London, 1946, republished 1970, S.R. Publishers Ltd., London, p78

- Edmund Lenihan; In the Tracks of the West Clare Railway; Mercier Press, Dec. 2008, p21-25.

- Edmund Lenihan; In the Tracks of the West Clare Railway; Mercier Press, Dec. 2008, p29-32.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=7&lat=53.3993&lon=-7.9500&layers=14&b=1, accessed on 7th April 2019.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=7&lat=53.3993&lon=-7.9500&layers=13&b=1, accessed on 7th April 2019.

- Edmund Lenihan; In the Tracks of the West Clare Railway; Mercier Press, Dec. 2008, p40-43.

- H. Fayle; Narrow Gauge Railways of Ireland; Greenlake Publications Ltd., London, 1946, republished 1970, S.R. Publishers Ltd., London, p81. These cars, No. 395 and 396, were, in fact, found not to be powerful enough to handle the gradients on the West Clare section of the railway. They were as a reult restricted to use on the more level Kilrush to Kilkee service.

- Of all the carriage works, only a carpenters’ shop, employing three men, was left by 1941.

- Edmund Lenihan; In the Tracks of the West Clare Railway; Mercier Press, Dec. 2008, p51-54.

- Edmund Lenihan; In the Tracks of the West Clare Railway; Mercier Press, Dec. 2008, p57-58.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=14&lat=52.9116&lon=-9.0299&layers=14&b=1, accessed on 9th April 2019.

- Edmund Lenihan; In the Tracks of the West Clare Railway; Mercier Press, Dec. 2008, p63-65.

- https://www.pandacoz.com/day-17—to-galway.html, accessed on 9th April 2019.

- http://forum.modelarstwo.info/threads/wagony-motorowe-w-europie.15235/page-6#lg=post-211343&slide=5, accessed on 9th April 2019.

- Edmund Lenihan; In the Tracks of the West Clare Railway; Mercier Press, Dec. 2008, p80-85.

- Patrick Taylor; The West Clare Railway; Plateway Press, 1994, p37.

- Patrick Taylor; The West Clare Railway; Plateway Press, 1994, p35.

- Patrick Taylor; The West Clare Railway; Plateway Press, 1994, p36.

Pingback: The West Clare revisited – Hyde Park Now

Thanks for including my house at Ruan.

The Ruan station house is now on the market!

No problems!

Thanks for sharing

Many thanks for putting together and sharing this project,

I just thought you might like links to two map sources I use when I’m looking up old railway lines in Ireland,

The 1913 OS Survey of Ireland is on The OSI Map viewer :

http://map.geohive.ie/mapviewer.html

(you need to zoom right in for the 25inch maps to work when the are selected,)

you can overlay aerial views with the old maps / Railway route,

The abandoned south route from Kilkee to Kilrush is very clearly mapped on this site, and may be of interest to you.

also 1913 was the first all Island survey, but there were two more detailed surveys,

in 1878 and the 1890s, They’re only of the large towns and cities, these are online in the UCD Library,

http://digital.ucd.ie/view/ucdlib:40377 ,

(the first map on each list is an index for the remaining maps)

There are only a few pieces of the WCR, and the Maps of Ennis are prior to the West Clare,

but perhaps these sources can be called on in a future project.

Thank you for your helpful response.

Wonderful!

But could you please correct the rather distracting ten occurrences of “Edmund Lenihan; In the Tracks if the West Clare Railway” to “Edmund Lenihan; In the Tracks of the West Clare Railway”?

Thank you Alan. My apologies! It is amazing when we check what we have written that we read what we think is there rather than what is there. I have made all the changes to this post now, I think.

Once again, thank you for taking the trouble to point this out.