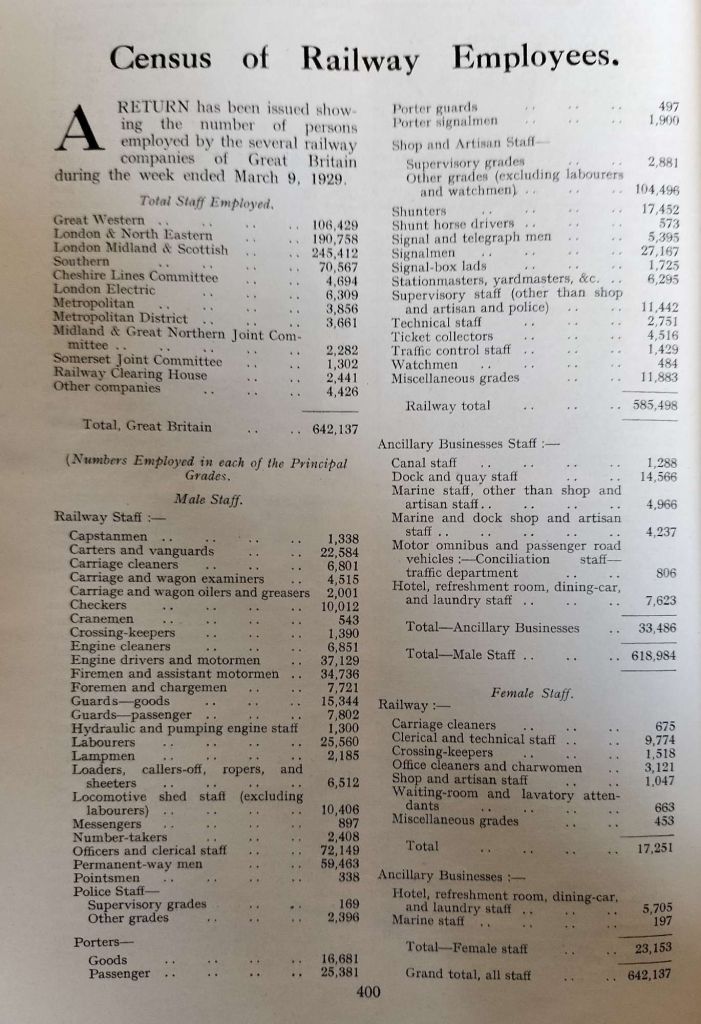

The Railway Magazine in November 1929 reported the breakdown of staffing across Britain’s railways in the week ending 9th March 1929. [1: p400]

It is interesting, first, to note the relative sizes of the staff numbers of the Big Four railway companies. Significantly the largest employer was the LMS. The LNER had around 55,000 less staff than the LMS. Strikingly, the GWR had significantly less staff again, with the SR the smallest, with less than one third of the staff numbers of the LMS. I wonder whether these figures might have resulted in some careful thinking, particularly by the LMS about the efficiency of their organisation? It would have been helpful to see the relative levels of income to compare against these figures. …

Secondly, I was struck by the relative numbers of male and female staff: 619,000 men to 17,000 women. 10 years after the first world war, very few of the women employed on the railways at that time would still have been employed by the railway companies. … What might have been the figures in a census during WW1?

Hidden within those figures are other striking comparisons. …

- There were 6,800 male carriage cleaners and only 675 female carriage cleaners.

- It seems that male officers and clerical staff totaled just over 72,000, supplemented by over 2,700 technical staff. Women employed in these areas amounted to around 9,800. It is unlikely that many supervisory positions in these areas would have been open to women, perhaps head offices of the railway companies may have had female managers in typing pools?

- The role of crossing-keeper seems to have been far more equitably staffed between men (1,400) and women (1,500). Often a station master’s wife (or the wife of another male employee) would be a crossing-keeper at a nearby crossing. One wonders whether there was a pay differential between men and women in this occupation?

- Cleaning roles for carriages and engines were given to men (13,600). Office cleaners were set alongside charwomen (3,100) and it appears that all lavatory attendants and waiting room staff were women (660).

- Shop and artisan staff are recorded separately. Men seem to have filled all supervisory roles (2,900) with 104,500 men in other grades (excluding watchmen and labourers). There were just over 1,000 women in similar roles.

- There were 7,600 male hotel, refreshment room, dining car and laundry staff and 5,700 women.

I am sure that as you look at the figures other matters will come to light.

I wonder what heading wheeltappers would be recorded under? Probably ‘carriage and wagon examiners’.

It also seems that in 1929 there was a ‘profession’ that trainspotters could aspire to. Across the railways of Britain there were 2,408 ‘number-takers’!

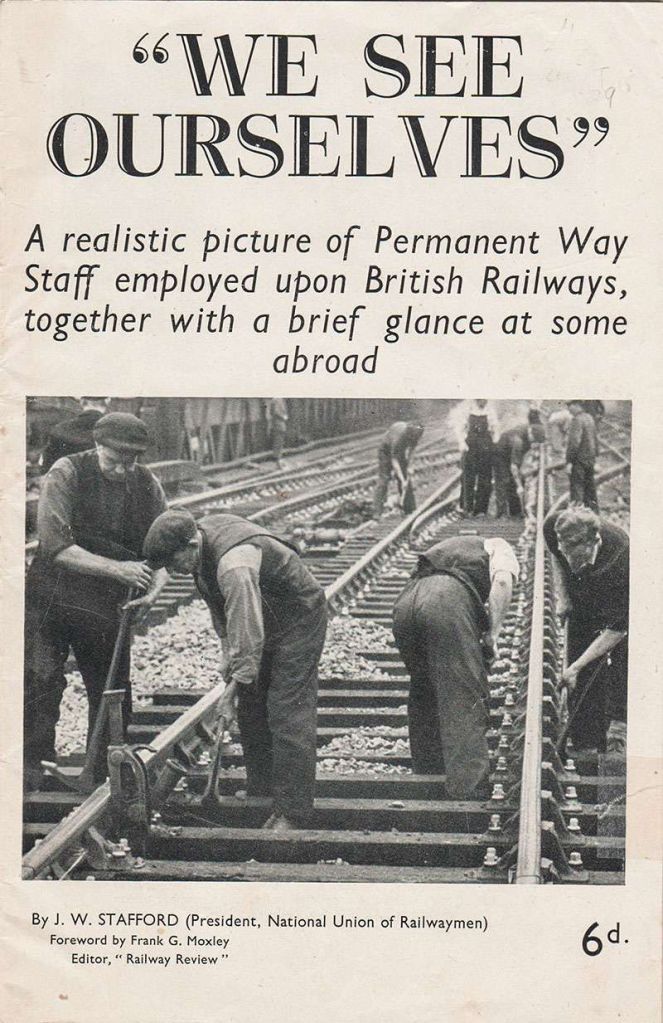

And finally … There are two pictures below showing railway employees at work on the railways. I came across the second while searching for a wartime image of women at work on the railways. The first is the cover page from the booklet which included the second picture. The “booklet, [was] published for six old pence in the BR era, by J W Stafford, the President of the NUR with the evocative title ‘We See Ourselves’. J W Stafford was a lengthman on the Great Western Railway, and later British Railways, for 33 years before he was elected president of the NUR in 1954. He asserted that it was management’s view in the 1930s that the heavier the tool, the greater would be the output of work, and that this belief had not entirely died out in the 1950s.” [2]

The foreword by Frank Mosley notes that “Credit for building a cathedral is seldom given to the men who carefully and skilfully laid the stones. It is the same with a railway – in building it and keeping it in good order.”

Didcot Railway Centre comments: “This booklet itself is a comprehensive and very honest reflection of all aspects of Permanent Way staff employment, its challenges and its future prospects. Extending to no less than 21 sections on 23 pages, it includes ‘As Others see us’; ‘We were the Pioneers’; ‘Our Girls’; ‘A Dangerous Occupation’; ‘The Whitewash Train’ to ‘Airing our Grievances’.” [2]

The section entitled ‘Our Girls’ is a frank reflection that wartime shortages of men caused females to be employed on this work. Stafford, writing in the BR era, considered that given the arduous and dangerous nature of normal activities, it simply wasn’t a suitable environment for women!

I suspect that today that thinking would be seen as sexist, even if it wasn’t in the mid-20th century. Women clearly proved themselves effective railway employees in both world wars.

References

- The Railway Magazine, November 1929.

- https://didcotrailwaycentre.org.uk/article.php/596/tuesday-treasures-march-2024, accessed on 30th July 2024.