I have been reading historic copies of the Railway Magazine again. This time it was a bound copy of the magazines from 1963. …….. I came across an article about the Railways of Jamaica in the September 1963 edition which was written by H. G. Forsythe. [1]

My previous article about the Jamaican network can be found at:

The Railways of Jamaica

Forsythe visited the island’s railways in the early 1960s and quotes figures from the late 1950s as part of his article.

In 1959, the Government “transferred ownership of the railway to a statutory corporation – the Jamaica Railway Corporation – which now [1963] operates the system.” [1: p644]

Forsythe talked in 1963, of the network having “some 205 route miles open to traffic, 112 miles being in the mountain sections. Mainline standard rail [was] 80 lb. per yd. and was laid on native hardwood sleepers. The highest point reached [was] at Green Vale, on the Montego Bay line, 1,705ft above sea level. This altitude [was] reached rapidly from the foothills and there [were] long stretches at a ruling gradient of 1 in 30 and right curves of a minimum radius of 320ft.” [1: p644]

Forsythe noted that the mountain sections of the network had a total of 41 tunnels which were cut straight through solid rock were generally unlined and had no portals.

Later in his article, Forsythe points out that the Jamaican railways “cover some of the most difficult standard-gauge mountain sections in the world. The schedule on the Montego Bay line [was] a generous 6 hrs and 45 mins allowed for the 112-mile run.” [1: p649]

He also commented that there were a total of 234 bridges/viaducts on the network. Some of these were combined road/rail bridges. He mentions 46 fully-staffed stations and 41 unmanned halts. The station buildings were to a standard design.

Wikipedia provides a full list of all the stations on the network on this link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_railway_stations_in_Jamaica

That link also includes a map of the rail network, [2] which appears below. …

When Forsythe was writing his article, the latest available statistical reports for the railway network were dated 1959. By that date the Bauxite industry on the island had become well-established. In 1959, the railways on the island carried passengers on 1,084,588 journeys [1: p645] and 900,000 tons of freight, [1: p644-645] including:

380,000 tons of Alumina; [3]

210,000 tons of Alumina processing materials; [3]

94,000 tons of bananas;

125,000 tons of sugar cane;

5,000 tons of citrus fruit;

15,000 tons of sugar; and

71,000 tons of general goods.

Rolling stock was largely of an American style. Forsythe notes that goods wagons were bogie-wagons with buck-eye couplings and Westinghouse air-brakes. He comments: “Box cars have the familiar American high handbrake wheels and ‘catwalks’ for the brakeman on top, the sides carrying gaily painted advertisements.” [1: p645] He also remarks on the Jamaican practise of converting goods wagons into ‘market cars’ which had seating provided inside a box car with added windows. On market days passengers were able to travel with their goods.

Train control used the block telegraph system, ” three telegraph lines emanate[d] from the Train Controller’s office at Kingston. … A dispatcher [was] in charge of each line and [was] linked by telegraph and telephone with each station … each station was similarly linked with every other station on its line.” [1: p645]

Signalling was “carried out by hand-held flags or lamps. Trains [could not] enter station areas until a yellow and green flag [was] displayed.” [1: p646] An additional precaution was employed at busier centres. … Trains were not permitted to move unless the pilotman was on-board. There was only one pilotman on duty in such centres. His duties included, “setting and locking points for incoming trains before walking to station limits to meet them.” [1: p646]

At the time of Forsythe’s visit, dieselisation of the motive power on the network was taking place. However, the steam locomotives were all oil-powered, so rather than seeing coaling stages, oil tanks and hoses were in place across the network.

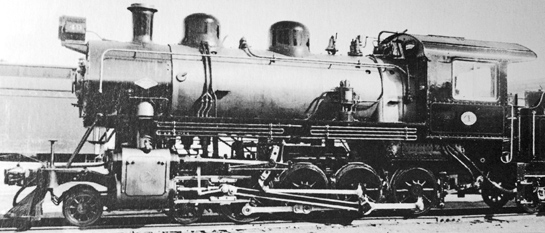

Forsythe provided an update on the locomotives available on the network at the time of his visit. He wrote: ” Motive power comprises, first and foremost, a rapidly vanishing group of superb-looking Canadian-built 4-8-0 steam locomotives. Designated classes ‘M1’, ‘M2’ and ‘M3’, they are all of the same general design and were built by the Canadian Locomotive Company between the years 1920 and 1944. Originally coal-burners, they were converted to oil after the last war when good quality coal became far too expensive. The maximum locomotive axle loading which the line can accommodate is 15.4 tons and the sharp curves restrict the rigid wheel-base to little more than 15ft.” [1: p647]

Built in Canada, these 4-8-0 locomotives were, according to Forsythe, the main stay of the Jamaican steam loco fleet. [5]

Built in Canada, these 4-8-0 locomotives were, according to Forsythe, the main stay of the Jamaican steam loco fleet. [5]

Forsythe continues: “These ‘Mastodons’ are typically American in appearance and are fitted with bells (now inoperative), ‘cowcatchers’, and electric headlamps. Cowcatchers are a very necessary piece of equipment, much livestock straying into the largely unfenced main lines.” [1: p647]

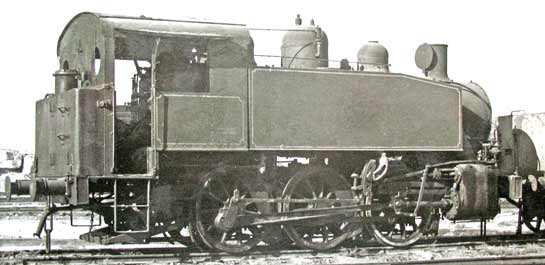

In addition to these 4-8-0s, there were a couple of US-built 0-6-0 tank shunting locos which Forsythe observed in Kingston Goods Yard working alongside a General Electric Bo-Bo 360 horsepower diesel-electric shunter.

US-built 0-6-0T locomotive. [5]

US-built 0-6-0T locomotive. [5]

He also came across an elderly 0-8-0T built by Liston & Co. of Leeds standing used in the roundhouse of Kingston MPD.

These steam locos are tabulated by J.D.H. Smith on this link: [4]

https://jdhsmith.math.iastate.edu/term/sljmjgr.htm

Forsythe also pointed out the innovative attitude of the management of the Jamaican railways. As early as 1938, “the internal combustion engine was in use in the form of s small fleet of 110-hp railcars supplied by D. Wickham & Co. Ltd., Of Ware. Some of these railcars are still in use and performing well. At least one has been thoroughly refurbished and painted in silver. It operates a popular and interesting rail tour from Montego Bay, known as ‘The Governor’s Coach’.” [1: p649]

More information about the developing use of Modern Traction in Jamaica can be found via Wikipedia: [6]

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Rail_transport_in_Jamaica

Forsythe refers to delivery of some Kalamazoo railcars from the US during the war. The name ‘Kalamazoo’ is now used in Jamaica to refer to any diesel railcar. He also mentions Metropolitan-Cammell units which were being delivered at the time of his visit, and a series of ten English Electric general-purpose Bo-Bo 750-hp diesel-electric locos. These EE locos were apparently mist successful under Jamaica’s arduous operating conditions.

References

1. H. G. Forsythe; The Railways of Jamaica; in The Railway Magazine, September 1963; p642-649. The full article can be accessed in the Railway Magazine Archive which is available for a subscription over and above the regular magazine subscription price.

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_railway_stations_in_Jamaica.

3. Alumina is produced from bauxite, an ore that is mined in various tropical and subtropical regions. Jamaica’s bauxite occurs in a series of deposits across the middle of the island, east to west. The largest deposits are in the parishes of St. Ann, Manchester, St. Elizabeth, and Trelawny. … The Bayer process, discovered in 1887, is the primary process by which alumina is extracted from bauxite. To produce pure aluminum, alumina is smelted using the Hall–Héroult electrolytic process.

4. https://jdhsmith.math.iastate.edu/term/sljmjgr.htm. Smith has tabulated a whole series of different locomotive rosters. This is just one table of many!