An essay written in 1998 as part of training to become an Anglican Priest.

INTRODUCTION

Susan Hill tells the story of a young woman, Ruth, whose husband dies suddenly. As Ruth works through her grief she is supported daily by Jo, the 14 year old brother of her dead husband. In the early months after the accident he is the only one who can reach into her grief (Hill: p9-116). Jo’s care of Ruth is effective care. He has no training but be deeply loves her

Christ has enjoined us to love our neighbour as ourselves. All questions of pastoral care, and particularly bereavement care, must start from the premise that all Christians, at the appropriate time and place, have something to offer, presumably love, in the first instance. This essay outlines the key issues in bereavement care and explores the different levels of care that a church congregation can provide to those working through the pain of loss.

1. THEORIES OF LOSS

Arnold van Gennep proposed a theory of loss in his book “Rites de passage” which has become generally accepted. He envisaged three main ‘stages’. A person experiencing loss starts in a ‘Prelminal’ stage caused by the separation, which is characterised by detachment, pain and anxiety; passes through a ‘Liminal’ stage of transition, characterised by ambivalence, distortion, chaos and loneliness; and gradually reaches a ‘Post-liminal’ stage of reincorporation back into the community, a time of new beginnings and moving on (from lecture by A. Chatfield). Much has subsequently been written about bereavement. William Worden talks of four tasks of mourning: accepting the reality of loss, working through the pain of grief, adjusting to an environment in which the deceased is missing, and emotionally locating the deceased and moving on with life (Worden p10ff) Ainsworth-Smith and Speck speak of three main phases: shock and disbelief, awareness, and resolution (Ainsworth-Smith: p5ff). Elizabeth Kubler-Ross suggests that dying patients and their families go through similar grief processes (Kubler-Ross: p150ff). She identifies five different stages: denial and isolation, anger, bargaining (more obvious in the terminally ill than in the bereaved), depression, and acceptance (ibid. p35-101). Colin Murray Parkes identifies a series of different behaviour patterns common among the bereaved, from broken hearts (and increased attendance at doctor’s surgeries) through alarm and stress, searching, mitigation, anger and guilt, to the gaining of a new identity. (Parkes p36-112)

These different theories all suggest a process which takes some considerable time. It would be possible to describe each individual stage in each theory but this is not necessary within the scope of this essay, the diversity of description of these stages serves to illustrate the fact that each individual responds to the loss associated with bereavement in different ways. Each author emphasises the need to recognise the way in which the individual is responding to their loss. Strath and Speck talk in a number of places of the way in which the various feelings tend to flow back and forth during the grief process like the tide coming in and out each day. Each time the tide comes in it can leave behind a different ‘response’ (eg. Ainsworth-Smith: p30-31). It must be appreciated that these theories are models to assist understanding rather than timetables for grief or routes through the grief process.

2. ATYPICAL GRIEF

Parkes points out that for some people the grief process can become distorted. He highlights two specific reactions “one was a tendency for grief to be prolonged, the other a tendency for the reaction to bereavement to be delayed.” (Parkes: p125). His work suggested that persistent panic attacks, persisting and intense guilt, intense separation anxiety, strong but only partially successful attempts to avoid grieving, and development by the patient of symptoms mirroring those of the deceased, were all associated with abnormal grief (ibid: p128). Worden outlines a number of factors which contribute to a falure to grieve. These fall into relational, circumstantial, historical, personality, and social categories. He considers abnormal grief under a series of headings: chronic grief reactions, delayed grief reactions, exaggerated grief reactions; and masked grief reactions (Worden: p73-74) Ainsworth-Smith and Speck identify the main distortions of the proces of grieving as delay, denial, prolongation and clinical depression (Amsworth-Smith p106-112).

Those caring for the bereaved need to be able to identify atypical grief if they are to be able to reassure those whose grieving is ‘normal” and be able recognise the need for greater help for others “Grief may be strong or weak, brief or prolonged, immediate or delayed, particular aspects of it may be distorted and symptoms that usually cause little trouble may become major sources of distress In some cases it may seem that a particular response is the consequence of a number of circumstances cach of which contributes to the outcome, in others, one factor may appear to be the chief determinant” (Parkes p136).

The texts refer to ‘determinants of grief’. Parkes suggests that there are a number of factors (determinants) which will influence the way people respond to loss – previous experience of loss, current issues (personality, sex, age, socio-economic status, nationality, religion and culture); and issues subsequent to the loss (support or isolation, other stresses, new opportunities).

3. SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES

Most of the authors referred to above write of the need to give special consideration to those grieving different kinds of death. Each loss will have its own unique issues but it is possible to group losses into some broad categories that enable the development of understanding. For example, Worden provides details of anticipated grief responses to suicide, sudden death, sudden infant death, miscarriages, still births, abortion, long term illness and AIDS (Worden: p93ff). He helpfully suggests appropriate caring responses for each case as part of his discussion.

4. WHAT DOES ALL THIS MEAN?

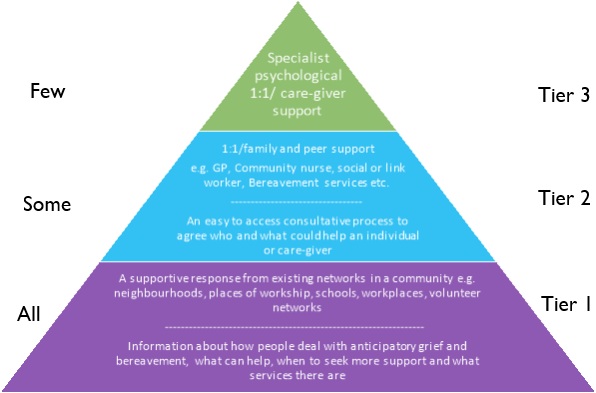

We have undertaken a rapid review of current thinking in relation to grief and the process of grieving. It illustrates the need for those involved in caring to have a thorough understanding of bereavement. It seems to indicate that care of the bereaved is something for experts or specialists. I want to suggest that, although there are clearly circumstances when only an expert will do, this is not just an area for the specialist. There is much that a caring Christian community can give to those experiencing bereavement. The remainder of this essay discusses such ministry and highlights gifts and qualities necessary for those involved in it.

5. A HIERARCHY OF CARE

All of us live within a complex network of social relationships, friends, immediate family, work, church and other acquaintances which is supplemented at different times by contact with specific professionals. Bereavement, at least temporarily, extends that social network as we are visited by funeral directors, clergy, extended family and, dependent on our need, by counsellors and therapists.

Society has its own pattern of care and there are now many organisations specialising in bereavement care. The church should not set itself up in competition with those who provide specialist support and counselling but may be able to offer some of these services if they are not available locally and may well be able to provide support for its own members without competing with others. In any locality, the church needs to work out a specific caring response to those who have been bereaved.

Care for the bereaved may involve prayer, practical support, listening, counselling and therapy. Members of the church will be involved in all levels of care either in a professional capacity or as members of the body of Christ. It is possible to think in terms of a hierarchy of care with professionals providing specialist care and other equally valid ministries being undertaken by ordinary people, such as church members, for which the primary qualifications are love, sensitivity and time. The church should encourage members of its congregations to enter the fields of counselling, and psychotherapy Church leaders should also be aware of Christians in their vicinity with these skills. There is, however, much more that a congregation can do than just referring those grieving to specialists. We will consider later the nature and development of appropriate qualifications for involvement in this ministry. Firstly we must consider the unique position and role of the clergy.

6. THE CLERGY

Those outside the church will often not meet a member of the clergy except in connection with one of the occasional offices baptisms, weddings and funerals. Wesley Carr calls these occasions ‘brief encounters’ (Carr: p11) Many funerals in the UK are still conducted by a religious figure, usually Christian. The minister has to become accustomed to ministering to those with no obvious belief. She or he seems to represent something significant. But most people would not be able to articulate what! He or she is probably believed to be able to manage everything that surrounds this final boundary to life. She or “he looked to as a man [or woman] of professed faith, who is believed to be able to face the spectre of death and, as it were, to defeat it. Whereas ordinary people are afraid of death and dying, the minister is supposed not to be. [She or] he is expected to be competent. His [or her] believed strength in the face of death and … ability to handle it produce a curious amalgam in people’s minds, whereby he [or she] may almost become the purveyor of death. As such, [she or]he is both needed and shunned” (ibid. p106-107). Because the minister has [her or] his own struggles, “the pressure upon him [or her] is to respond by acting a part, so that [she or] he may meet the expectations of [their] audience and not be hurt [themselves]” (ibid: p107).

The funeral is a very significant part of the bereavement process and is therefore a major pastoral ministry that the church is able to offer to the community. Early in the bereavement process, it serves to crystallise the immediate realities, that a person has died and that the living have to do something about this. It provides a fixed reference point to which people can relate as they work through the bereavement process. It becomes crucial to the way that the family remembers the dead relative.

The clergyperson, therefore, has a vital role of directing the funeral service (as a kind of choreographer of grief), articulating in the service things that the bereaved may not be able to articulate themselves, and allowing the appropriate expression of feeling “People under stress surrender to him [or her] an alarming amount of power, which [she or] he has to hold with astuteness. As a Christian he [or she] may be tempted to respond with almost glib talk of life after death, rather than profound exploration of the gospel emphasis that life is in the midst of death” (ibid. p117).

“A considerable investment may be held even by those who have no formal religious belief m the representative role of the muruster in terms of unchangingness and security. But her [or his] ability to behave, and sometimes say things, which may sensitively challenge the established expectations may also be crucial” (Ainsworth-Smith: p116)

It is important that members of the clergy are able to engage with their own issues of loss, their own fears of death, and their own mortality, so that they grow in self understanding, Failure to do so will prevent effective involvement in the losses of others. The clergy also need to be aware of the processes of grieving, being able to judge when the grieving process has become distorted. They need to be able to counsel and to listen but must be able to judge their own limitations for caring (through lack of time, interaction with their own issues, or where care requires more professional involvement).

7. THE BODY OF CHRIST

The local church, or the body of Christ, has much to offer to the bereaved. Firstly, through its corporate nature, it is a living and theological resource for the community (Gal 6:2,10). The church should be the one place above all others where people are welcomed into a loving community which cares for its members and for outsiders (Rom. 12:4-5; 1 Cor. 12:12-27, Eph 4:1-6); a place where we carry each other’s burdens. It is a place where death and loss can be faced in a community that is centred on the suffering and death of Christ. It is a place where Christ’s death is regularly ‘made real’ in Holy Communion. It can offer services for the bereaved, such as funerals, requiems, thanksgiving services, services for loss of babies, and anniversary services. Each of these meets specific needs and is surrounded by opportunities for care. The church has various fellowship and support groups (home-groups. Mothers Union, youth groups, men’s groups) which have been learning to care for each other at a deeper level than much of the rest of the community. There is a sense in which, at times, care which comes from a community seems much stronger and mere effective than that from a few individuals.

Secondly, the individual members of the body of Christ have different gifts to offer. We considered possible areas of ministry earlier in this essay. It is important that those involved in the care of the bereaved are personally prepared for their ministry through engagement with their own experiences of loss, fears of death and mortality. It is important that they understand the process of grieving and that it will essentially be unique to each person that they care for. The level of training appropriate for ministry will vary dependent on the person’s involvement, those offering a listening or immediate prayer ministry will need more training than those who see their ministry as limited practical care or more remote prayer. Likewise the natural capabilities required of those ministering will depend on their role. Qualities necessary for ministry to the bereaved would to a greater or lesser degree include listening skills, transparency, durability, adaptability, time and commitment, approachability, experience of loss or bereavement; honesty before death, and a lack of their own agenda. it is also important that this ministry is clearly ‘other focused’ and that people are not trying to work out their own grief through caring for others.

8. DEVELOPMENT OF CARING CONGREGATIONS

We have discussed many of the specific areas of care that a congregation can offer. We have noted that, as its pastoral care structures develop, there will be a natural sense in which care for all people and also, therefore, for the bereaved will develop. Specific training in specialist skills will be appropriate for some members of the congregation; particularly in counselling, listening skills, and bereavement visiting. A congregation should be encouraged to engage with individual and corporate loss at all levels – the teaching of the church should touch this area regularly; home-groups should work together on recognising their own sense of loss and consider what ministry they, as a group, might have in this area, at times of change in the church, the element of loss should be acknowledged and faced; individuals should be helped to face their own fears of death and their own mortality.

CONCLUSION

Towards the end of Susan Hill’s novel Ruth visits Potter who had been present when her husband died. They share together the events of that day:

“Without any warning, the tears rose up and broke out of her, and Potter sat on his chair saying nothing, and yet being a comfort to her, taking some of her grief on to himself. She wept as she had never wept before in front of another human being, and it was a good thing to do; it was more value than all the months of sobtary mourning. It brought something to an end” (Hill: p135).

The local church is in a unique position to provide both community and individual care to those experiencing bereavement. The aim of all of its ministry in this area must be to provide space to allow each individual to grieve in the sure knowledge that they are, and will always be, accepted and loved, both by special friends and the whole church community.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Susan Hill; In the Springtime of the Year; Penguin, London, 1977, (International Edition, 5th April 2012).

- Wesley Carr; Brief Encounters: Pastoral Ministry through the Occasional Offices; SPCK, London, 1985.

- Elizabeth Kubler-Ross; On Death and Dying; Tavistock, London, 1970.

- Colin Murray Parkes; Bereavement: Studies of Grief in Adult Life; Penguin, London, 1986.

- J. William Worden; Grief Counselling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner; Routledge, London, 1991.

- Ainsworth-Smith & P Speck; Letting Go: Caring for the Dying and Bereaved; SPCK, London, 1982.

- Public Health Palliative Care: developing a community response to Covid-19 pandemic; written evidence submitted by the Royal College of General Practitioners (DEL0327); via https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/9415/html, accessed on 14th April 2025.