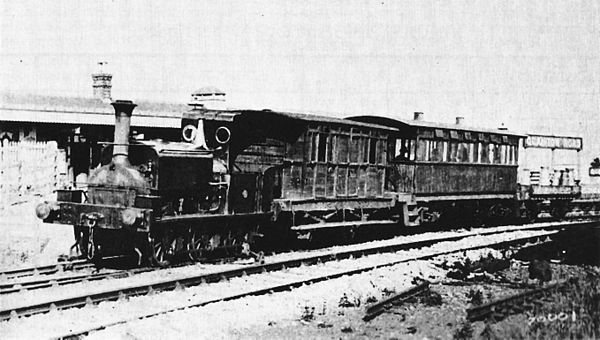

The featured image above is of the Aveling & Porter locomotive known as ‘Old Chainey’, one of two unusual steam locomotives which served the line in early days. [29]

One of the delightful things about reading early copies of The Railway Magazine is the perspective from which articles are written. In this particular case the existence of the Great Central Railway is a welcome novelty!

This article begins: “Quainton Road is a name which has of late become familiar to the railway public owing to its being the converging point of the lines of the Great Central Railway’s recently-opened extension to London with those of the Metropolitan. It is situated in Buckinghamshire, at a distance of 45 miles from London” [1: p456]

Goodman goes on to refer to the Great Central as being “destined to become a power in the land.” [1: p456]

With the benefit of hindsight, whatever could be said about the Great Central during its lifetime, we know that it has not survived as a main line!

“The Great Central Railway [GCR] in England was formed when the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway changed its name in 1897, anticipating the opening in 1899 of its London Extension.” [2]

It survived as an independent company until, “on 1st January 1923, the company was grouped into the London and North Eastern Railway.” [2]

Ultimately, “the express services from London to destinations beyond Nottingham were withdrawn in 1960. The line was closed to passenger trains between Aylesbury and Rugby on 3 September 1966. A diesel multiple-unit service ran between Rugby Central and Nottingham Arkwright Street until withdrawal on 3 May 1969.” [2]

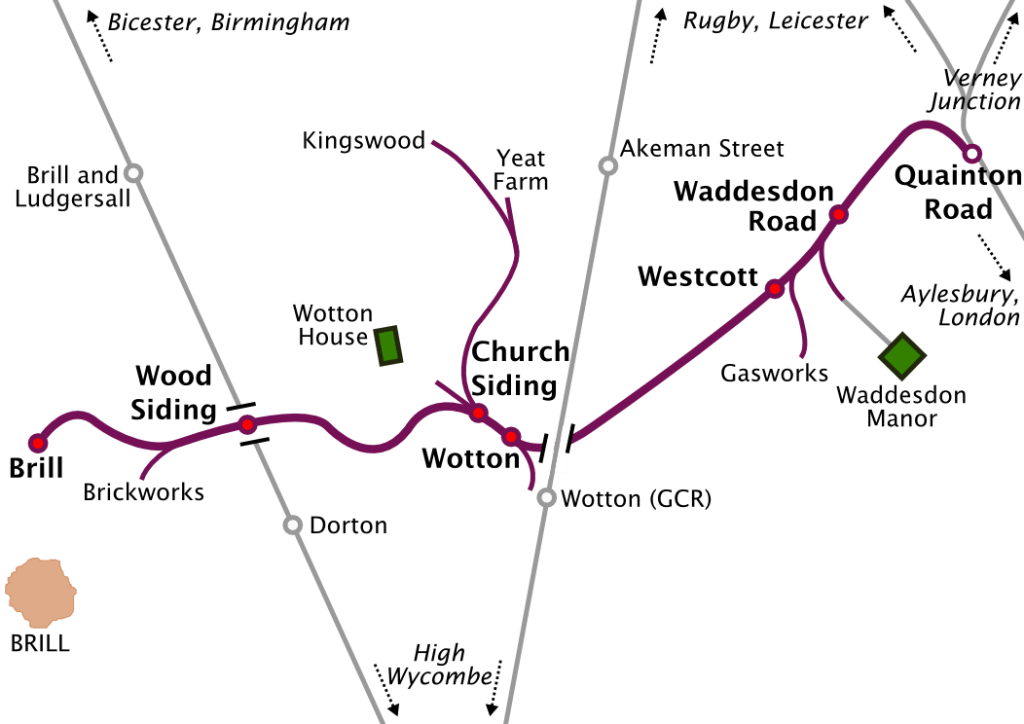

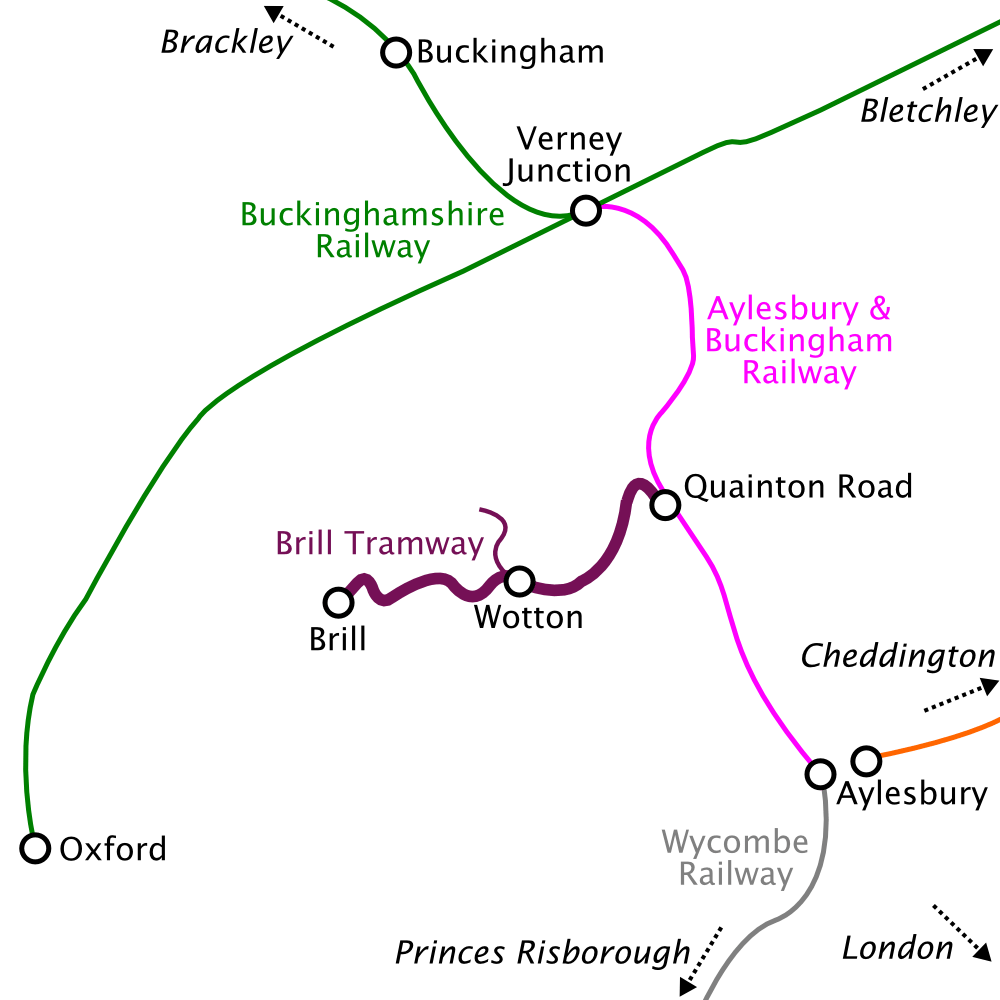

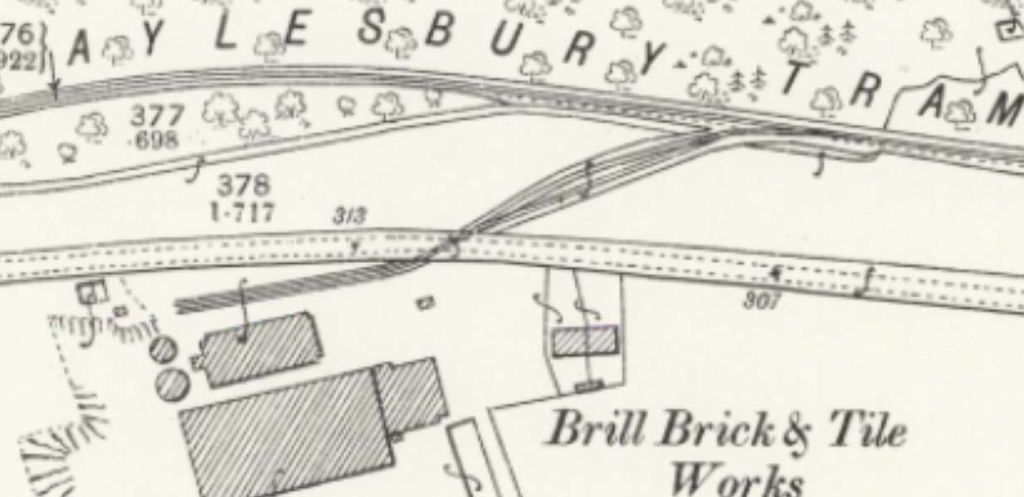

But this article is not about the GCR. It is about what Goodman describes as a “useful but little-known line … Called the Oxford and Aylesbury Tram Road.” [1: p456] The name is somewhat of a misnomer, as the line depended on the Metropolitan service between Aylesbury and Quainton and only ever ran as far as Brill, with a population of 1,300. It was only 6.5 miles in length. It was known during its lifetime by a number of different names: the Brill Tramway; the Quainton Tramway; the Wotton Tramway; the Oxford & Aylesbury Tramroad; and the Metropolitan Railway Brill Branch.

“In 1883, the Duke of Buckingham planned to upgrade the route to main line standards and extend the line to Oxford, creating the shortest route between Aylesbury and Oxford. Despite the backing of the wealthy Ferdinand de Rothschild, investors were deterred by costly tunnelling. In 1888 a cheaper scheme was proposed in which the line would be built to a lower standard and avoid tunnelling. In anticipation, the line was named the Oxford & Aylesbury Tramroad.” [3]

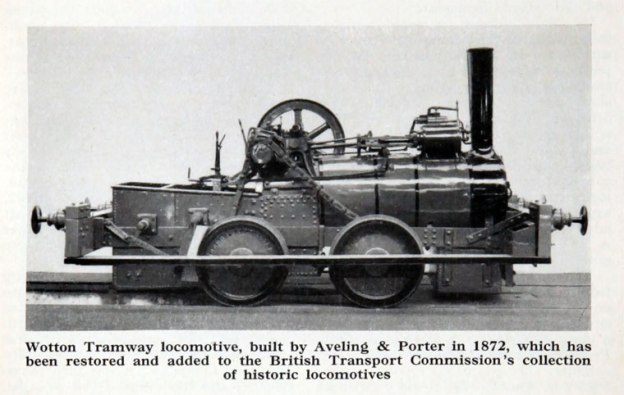

The first locomotives on the line were particularly unusual. Built by Aveling and Porter of Rochester, they arrived on the line in 1872, at which time the line was known as the Wotton Tramway.

A previous article looked at these Aveling and Porter locomotives among other unusual locomotives. Goodman says that “the early locomotive stock of the tramway consisted of two four-wheeled engines, which would now-a-days present a more or less unique appearance by the side of more modern types of locomotion.” [1: p457]

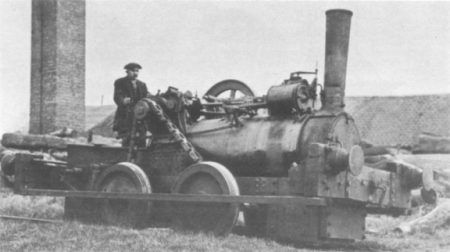

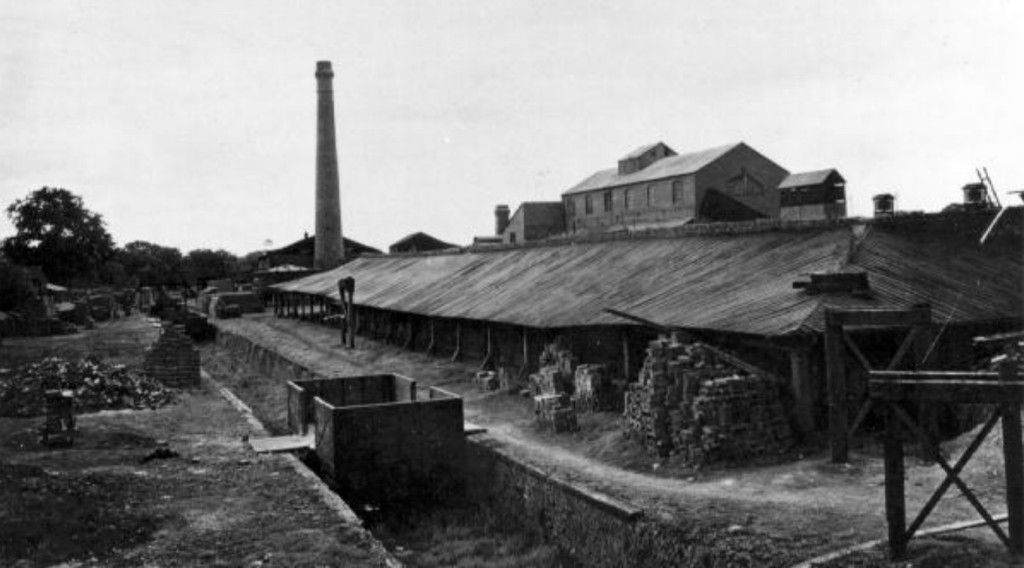

“Old Chainey” is a chain and flywheel-driven loco built in 1872. It was one of two locomotives on the line between Quainton Road and Brill. It was not very successful, especially if loads were heavy. It lasted in service on the Tramway until 1895 when it was sold for use at Nether Heyford Brickworks in Northamptonshire, where it continued working until the Second World War. [5]

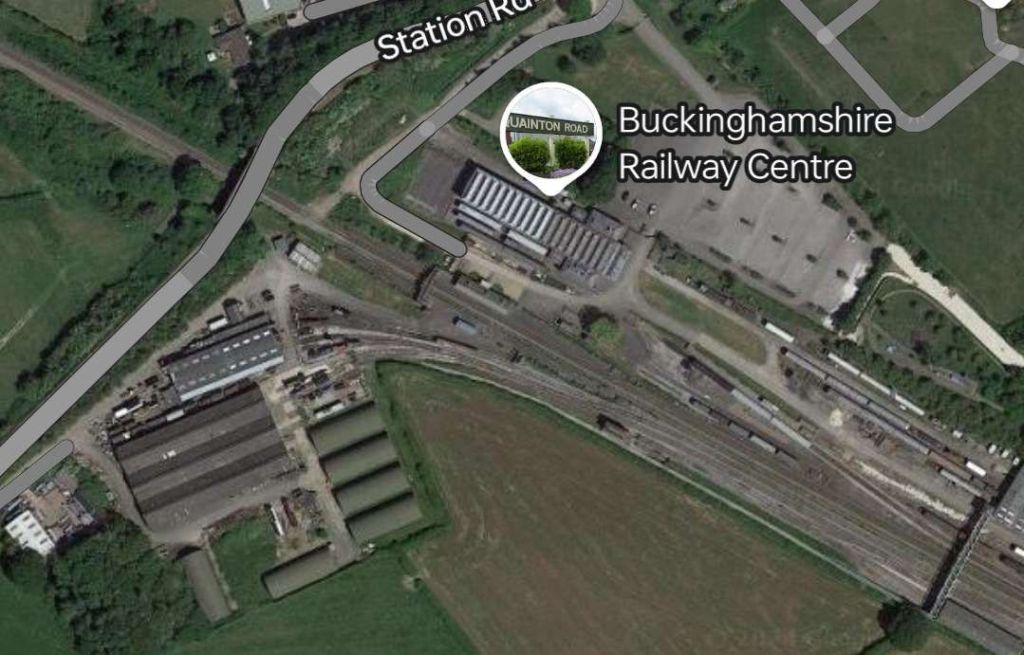

It is now a static exhibit. It was placed, first at the London Transport Museum and then on long-term loan from the London Transport Museum to the Buckinghamshire Railway Centre. [6]

Goodman continues: “In general design [the locomotives] were not unlike the familiar traction engine, being built upon the same principle. Each engine had only one cylinder, which was situated above the boiler. Motion was accordingly imparted to a fly-wheel placed near the foot-plate, which, being connected with the running (not driving) wheels by a chain passing round their axles, caused the engine to move. The dimensions of the cylinders were 7 in. in diameter and 10 inches stroke. The wheels on the rails were 3 ft. in diameter. Both engines had long chimneys, fitted with caps to prevent the emission of sparks. For the accommodation of the enginemen, cabs – in reality little more than weather-boards – were provided, and at each side, about 18 in. above the rail-level, a footboard was fixed. …. The speed attained by them would hardly be termed ‘express’, the time occupied on the 6.5 miles from one terminus to the other averaging about 90 minutes!” [1: p457] That is just over 4 mph.

The line was upgraded in 1894, but the extension to Oxford was never built. “Instead, operation of the Brill Tramway was taken over by London’s Metropolitan Railway and Brill became one of its two north-western termini.” [3] The Aveling and Porter locomotives appear to have remained in service until 1895.

No. 807 was sold for industrial use. It appears in the adjacent image at Nether Heyford Brickworks on 11th April 1936, © G. Alliez. This image accompanies an article from ‘The Engineer’ reproduced by the Industrial Railway Society. [5]

The nickname “Old Chainey” appears to result from the noisy operation of these locos. The one on static display at Buckinghamshire Railway Centre is Aveling and Porter No. 807. It was the first of the two locomotives converted for use on the Tramway. They cost £398 each. [7: p13] It was delivered to the Tramway in January 1872. The second loco was delivered in September of the same year. [7: p18][8: p29]

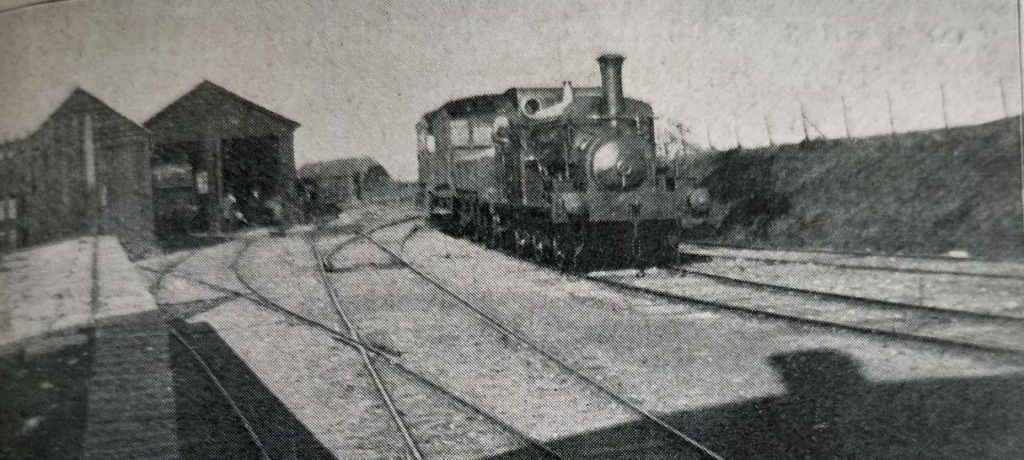

Before the writing of Goodman’s article in 1899, probably as early as 1895, more advanced locomotives were introduced, allowing trains to run faster. Goodman comments that the Aveling and Porter locos were: “superseded by two smart little locomotives of a more modern design. They [were] Huddersfield No.1 and Brill No. 2. and were built by Messrs. Manning, Wardle and Co., Boyne Engine Works, Leeds, the former in 1878 and the latter in 1804. Both [had] six wheels, all coupled, saddle tanks, and inside cylinders, with a total wheel-base of 10 ft. 9 in. and when in working order they each [weighed] about 10 tons. The wheels [were] 3 ft. in diameter, and the cylinders 12 in. in diameter, with a stroke of 17 in.” [1: p458]

The rural nature of the area meant that passenger traffic on the line was never particularly high. “The primary income source remained the carriage of goods to and from farms. Between 1899 and 1910 other lines were built in the area, providing more direct services to London and the north of England. The Brill Tramway went into financial decline.” [3]

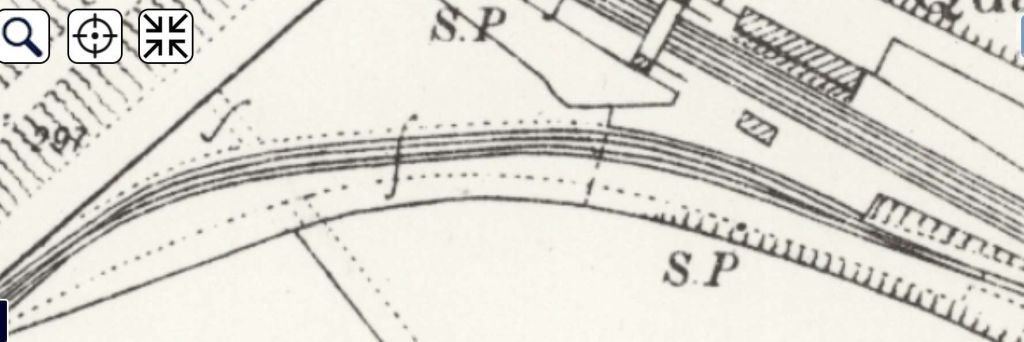

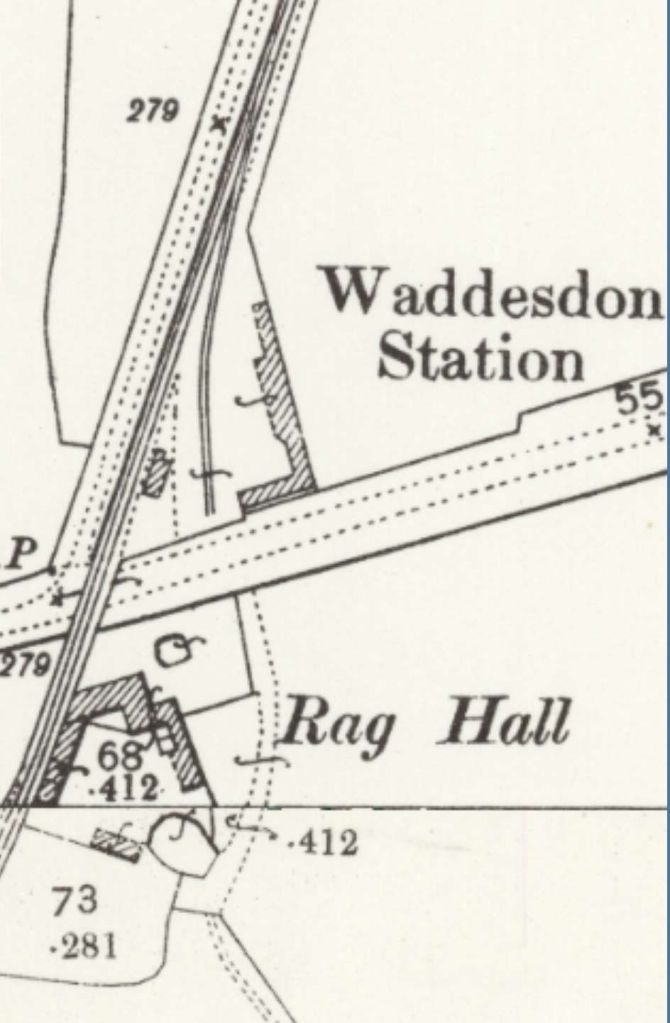

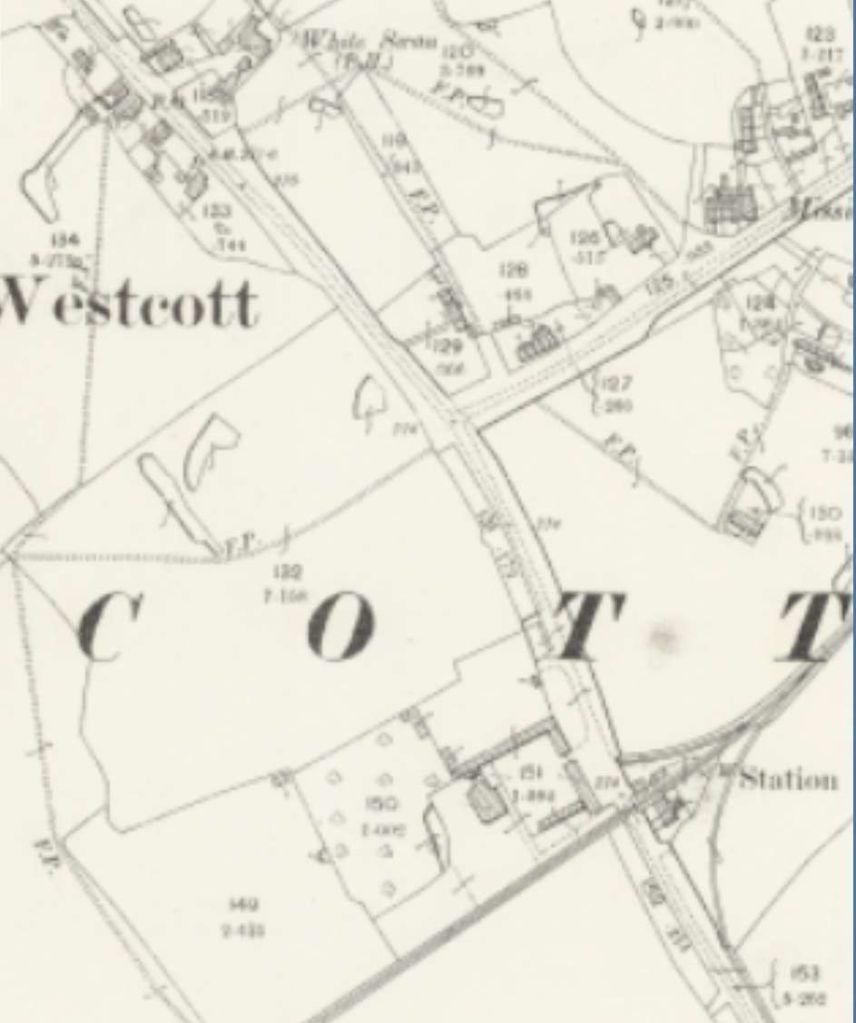

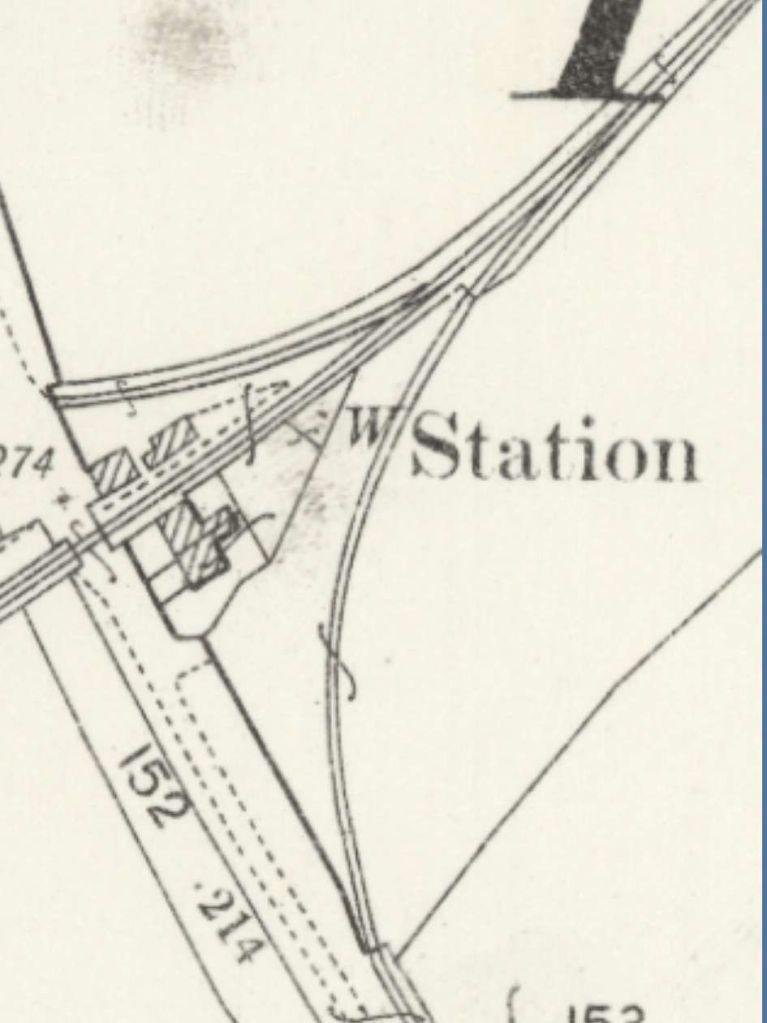

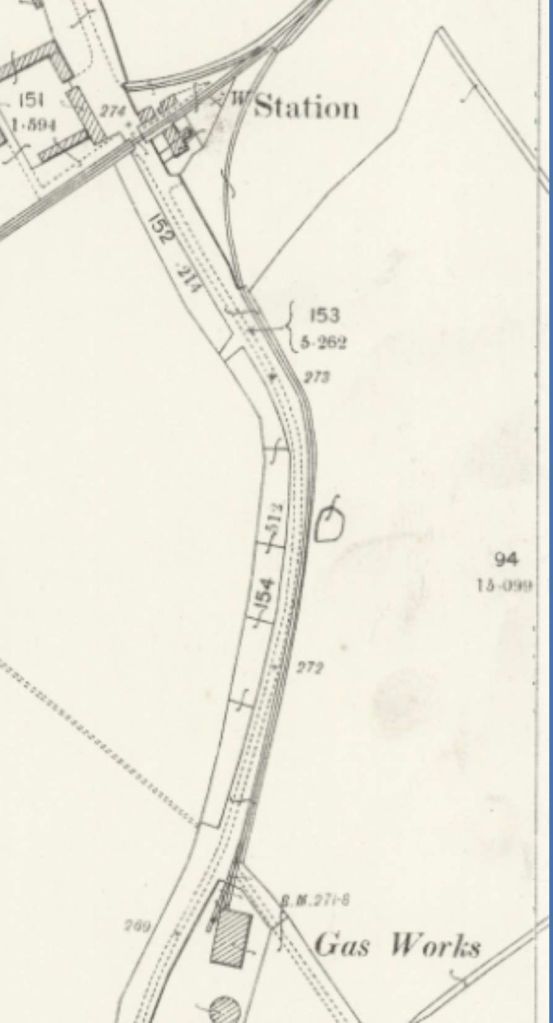

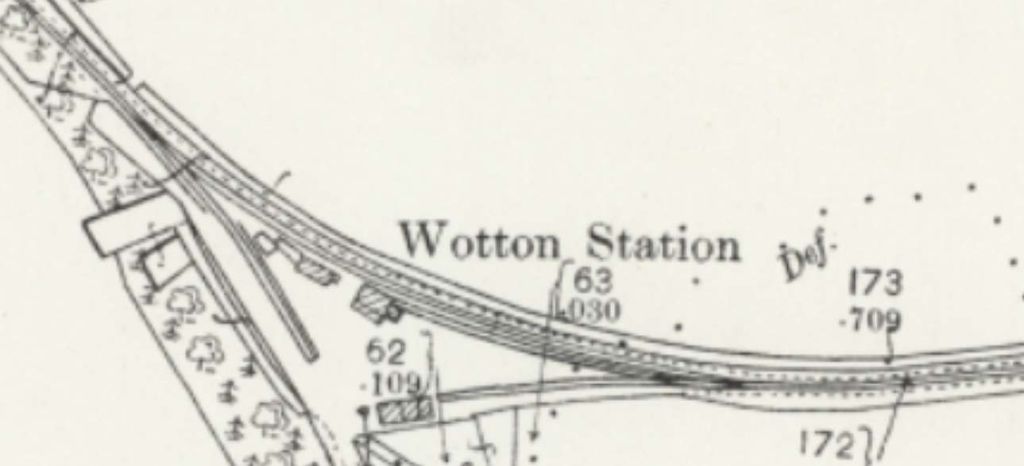

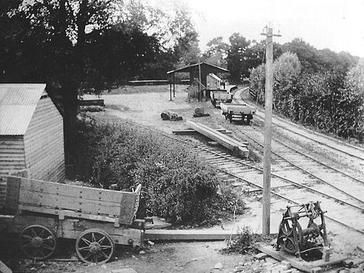

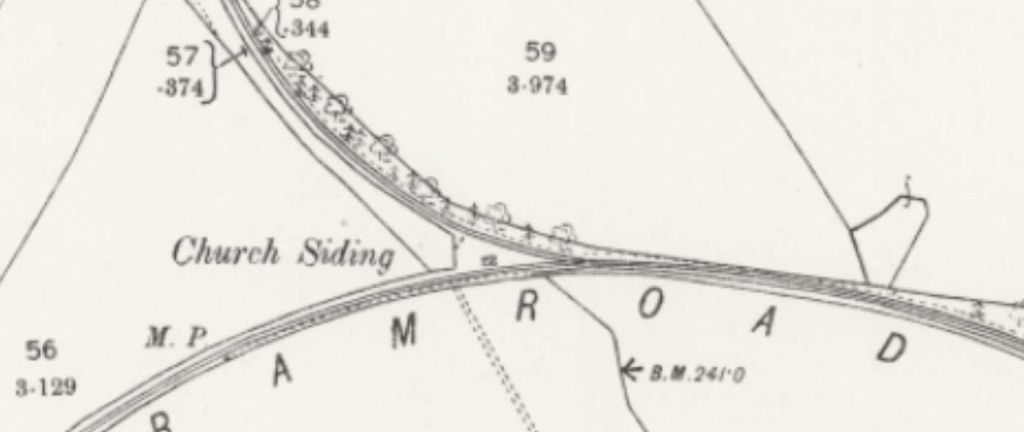

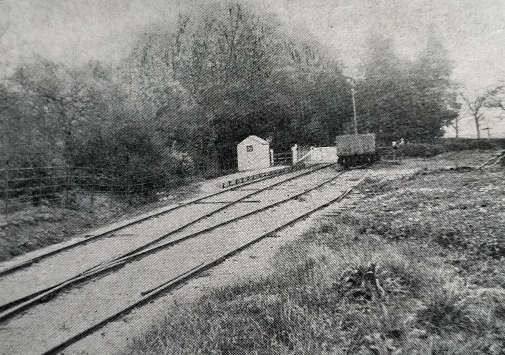

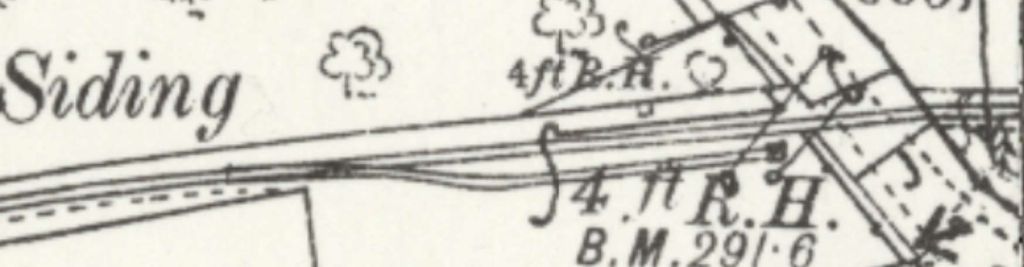

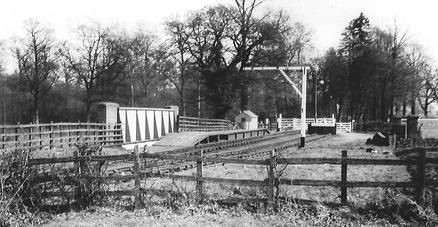

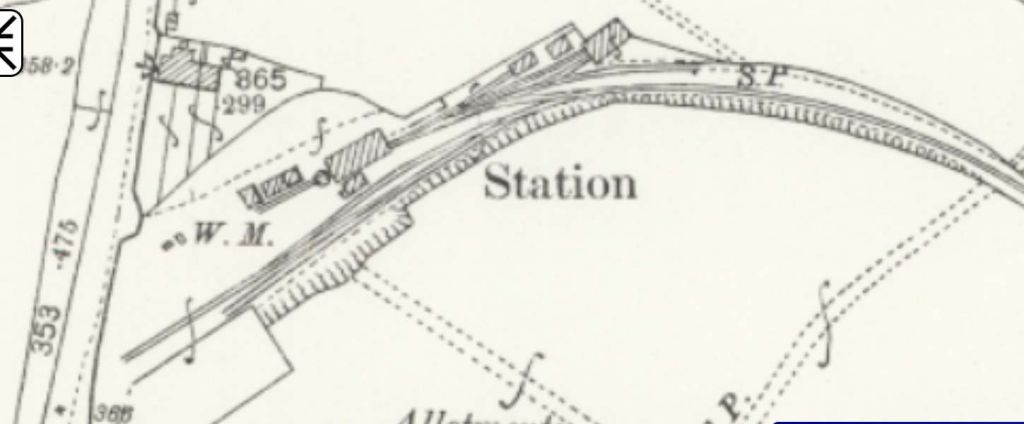

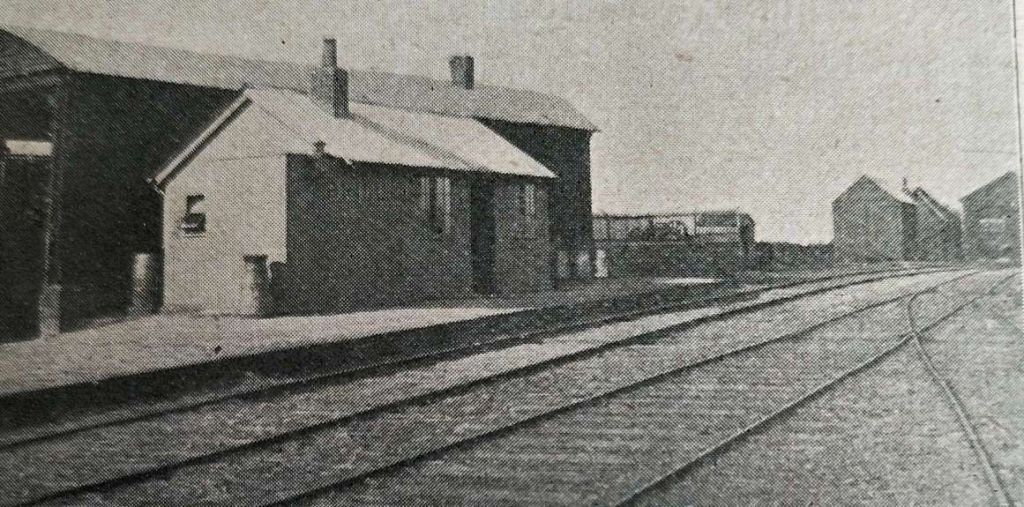

In 1899, Goodman reported that “the traffic receipts of this little line have always been gratifying to the proprietors, and in 1894 the reconstruction of the tramway was sanctioned, and, as previously mentioned, it was decided to carry it through to Oxford. The old light rails have been replaced by flat-bottomed ones spiked directly on to transverse sleepers, but in some places bull-headed rails and chairs are utilised. The banks of earth which originally did duty for platforms have made way for small but serviceable stations, of which there are four, besides those at the two terminal points, viz Waddesden, Westcott, Wotton, and Wood Siding.” [1: p458]

Goodman also commented that “the train service was also smartened up although the speed of ten miles per hour [was] never exceeded. There [were] four trains each way daily (Sundays excepted), which [ran] at the following times: [departing Brill] 8.10, 10.30 am, 3.05, 5.05 pm, [arriving Quainton Road] 8.53, 11.10 am, 3.45, 5.50 pm; [departing] Quainton Road 9.30 am, 12.15, 4.15, 6.25 pm, [arriving Brill] 10.10 am, 12.55, 4.50, 7.00pm. … None of the trains [were] timed to stop at the intermediate stations except Wotton, unless required. Passengers and goods [were] conveyed by all trains, which [were] thus ‘mixed’, and their ‘make-up’ would certainly provoke a smile when seen for the first time.” [1: p458] The ‘consist’ was made up of a combined carriage and luggage van, one (or sometimes two) bogie coach(es) with an open interior, and an open ‘low-sided’ goods wagon which often was seen with one or two milk churns. All passengers were charged a standard 1d/mile and there was no first class accommodation. The line was worked on a single-engine in steam principal which meant no signals except on approaches to level-crossings. Goodman notes that the line was only separated from roads and adjacent property by a light wire fence.

When the line was independent, its head offices were at Brill, as was the engine shed, which sat alongside the line on the approach to Brill Station. A further two or three sidings were dedicated to the handling of goods. The station sat about a mile from the centre of Brill.

Goodman also notes that the construction of the line posed no significant difficulties. He comments that “the tram road [was] a party to the Railway Clearing House so far as goods and parcels traffic [was] concerned.” [1: p459]

In 1899, through booking of passengers was not in operation, “in fact, the neighbouring companies completely ignore[d] the existence of the tram road in their time tables, and some omit to show it on their maps.” [1: p460]

Goodman expressed confidence that “when the extension to Oxford [was] opened [the line would] necessarily assume a position of more importance.” [1: p460] As we will see below, that confidence was misplaced.

In 1933, the Metropolitan Railway became the Metropolitan line of London Transport. The Brill Tramway became part of the London Underground, despite Quainton Road being 40 miles (64 km) from London. London Transport focussed on “electrification and improvement of passenger services in London and saw little possibility that passenger routes in Buckinghamshire could become viable. In 1935 the Brill Tramway closed.” [3]

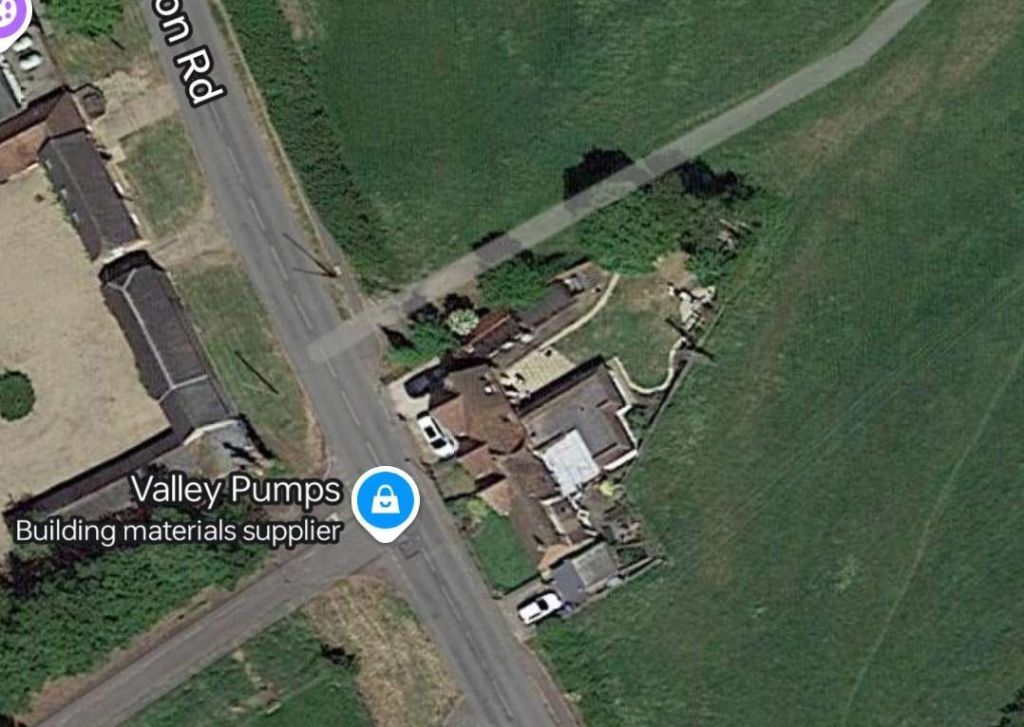

“After closure, the line was largely forgotten. Because it had been built on private land without an Act of Parliament, few records of it prior to the Oxford extension schemes exist in official archives. At least some of the rails remained in place in 1940, as records exist of their removal during the building of RAF Westcott.[139] Other than the station buildings at Westcott and Quainton Road almost nothing survives of the tramway; much of the route can still be traced by a double line of hedges.[154] The former trackbed between Quainton Road and Waddesdon Road is now a public footpath known as the Tramway Walk.” [3]

References

- F Goodman; The Oxford and Aylesbury Tram Road; in The Railway Magazine, London, November 1899, p456-460.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Central_Railway, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brill_Tramway, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2020/01/02/unusual-small-locomotives-and-railcars-part-1.

- The Industrial Railway Record Volume No. 48, p34-38; https://www.irsociety.co.uk/Archives/48/AP%20Locos.htm, accessed on 1st January 2020.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brill_Tramway, accessed on 1st January 2020.

- Ian Melton, From Quainton to Brill: A history of the Wotton Tramway; in R. J., Greenaway (ed.). Underground, Hemel Hempstead: The London Underground Railway Society, 1984.

- Bill Simpson; The Brill Tramway; Oxford Publishing, Poole, 1985.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=14.9&lat=51.82535&lon=-1.05072&layers=168&b=1&o=100, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.3&lat=51.83247&lon=-1.04764&layers=168&b=1&o=100, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.1&lat=51.83240&lon=-1.03493&layers=168&b=1&o=100, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://astonrowant.wordpress.com/brill-railway, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/20203, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wood_Siding_railway_station, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.1&lat=51.83569&lon=-0.99960&layers=168&b=1&o=100, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.1&lat=51.83569&lon=-0.99960&layers=168&b=1&o=100, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.4&lat=51.83346&lon=-0.99245&layers=168&b=1&o=100, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.7&lat=51.86500&lon=-0.92835&layers=168&b=1&o=100, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.4&lat=51.85280&lon=-0.94702&layers=168&b=1&o=100, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.4&lat=51.84634&lon=-0.95742&layers=168&b=1&o=100

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.8&lat=51.84506&lon=-0.95559&layers=168&b=1&o=100, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.84381&lon=-0.95549&layers=168&b=1&o=100, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Wotton_station_(Brill_Tramway)_1906.jpg, accessed on 13th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brill_railway_station, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://files.ekmcdn.com/c8ed37/images/train-at-brill-railway-station-in-1935-london-transport-rpc-postcard-173348-p.jpg, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waddesdon_Road_railway_station, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/the-collection?query=Wood+siding&date%5Bmin%5D=&date%5Bmax%5D=&sort_bef_combine=search_api_relevance_DESC&f%5B0%5D=makers%3APamlin+Prints, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://www.railwayarchive.org.uk/getobject?rnum=L2625, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Wotton_Tramway, accessed on 16th September 2024.