E.E. Speight tells of his own experiences travelling by rail in Norway. In an article which is primarily a travelogue rather than a technical piece. He fails to mention the gauges of the different railways that he travels along. [1] The matter of the differing gauges of railways in Norway is covered in some paragraphs below.

In 1899, Norway had around 1,300 miles of railway. The principal elements were lines running:

- from Christiania South towards Sweden reaching the border at Kornsjo (169 km – the Smaalensbanen);

- from Christiania East towards Sweden reaching the border beyond Kongsvinger;

- from Christiania to Trondhjem (562 km) with branches to Lillehamer, Otta and from Elverum to Kongsvinger;

- from Trondhjem to Storlien (108 km) to meet the line in Sweden from Stockholm;

- from Christiania South to Drammen, Laurvik and Skien (204 km) with branches to Randsfjord, Kongsberg and Kroderen, Horten and Brevik.

- between Christiansand and Byglandsfjord (Saetersdal); Stavanger and Ekersund (Jaederbanen); and Bergen to Vosse (108 km).

The city of Oslo was founded in 1024. In 1624, it was renamed Christiania after the Danish king; in 1877, the spelling was altered to Kristiania. In 1925, it reverted to its original medieval name of Oslo.

It seems as though E.E. Speight may have missed the 1877 memo about the renaming of the city, and so continued to refer to Kristiania as Christiania. Reading in the 21st century we need to read Christiania as Oslo.

In the 21st century, the Norwegian railway system comprises 4,109 km of 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) (standard gauge) track of which 2,644 km is electrified and 274 km double track. There are 697 tunnels and 2,760 bridges. [2]

This was not the case in the early years of the network. The first railway in Norway was the Hoved Line between Oslo and Eidsvoll and opened in 1854. The main purpose of that railway was to move lumber from Mjøsa to the capital, but passenger service was also offered. In the period between the 1860s and the 1880s Norway saw a boom of smaller railways being built, including isolated railways in Central and Western Norway. The predominant gauge at the time was 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) (narrow gauge), but some lines were built in 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) (standard-gauge), particularly where those lines connected to the standard-gauge lines of Sweden. [2]

When building the Norwegian Trunk Railway (1850-1854), Robert Stephenson built the line to British standard gauge. This line was very expensive; Pihl argued that narrow-gauge railways would be less expensive to construct, he argued successfully for 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge. During the railway construction boom of the 1870s and 1880s all but the Kongsvinger Line, the Meråker Line and the Østfold Line were built with narrow gauge, leaving Norway with two incompatible systems. [7]

The 3ft 6in gauge was chosen by Carl Pihl in 1857 as the ‘standard-gauge’ for Norwegian railways. Pihl was a civil engineer and director of the Norwegian State Railways (NSB) from 1865 until his death in 1897. [7]

A number of main line railways were built to the 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm), to save cost in a sparsely populated mountainous country. This included: the Hamar – Grundset Railway which commenced operation in 1861; the more challenging Trondheim – Støren Railway which commenced operations in 1864; and Norway’s first truly long-distance line, the Røros Line, connecting Oslo and Trondheim (in 1877).

In 1883 the entire main railway network had been taken over by Norwegian State Railways (NSB), though a number of industrial railways and branch lines continued to be operated by private companies. [2]

It was the decision of the Norwegian Parliament to construct the Bergen line to standard-gauge (in the year following Phil’s death), which finally settled the debate over gauges. By this time, it had been demonstrated that standard-gauge lines built to the same specifications as the narrow gauge could be constructed at the same cost. [7]

Ultimately, all narrow-gauge lines owned by the NSB were either closed or converted between 1909 and 1949, at a cost many times larger than the initial savings of building them narrow.

Projects such as the Bergen Line and the Sørland Line (also built to standard-gauge) were connecting all the isolated railways and transshipment costs were becoming significant. [7]

Some private railways had 750 mm (2 ft 5 1⁄2 in) and one had 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) gauge. A few railways are in part still operated as museum railways, specifically the Thamshavn Line, Urskog–Høland Line and the Setesdal Line. [3]

The Thamshavn Line (Norwegian: Thamshavnbanen) was Norway’s first electric railway, running from 1908 to 1974 in what is now Trøndelag county. Today it is operated as a heritage railway and is the world’s oldest railway running on its original alternating current electrification scheme, using 6.6 kV 25 Hz AC. It was built to transport pyrites from the mines at Løkken Verk to the port at Thamshavn, as well as passengers. There were six stations: Thamshavn, Orkanger, Bårdshaug, Fannrem, Solbusøy and Svorkmo. The tracks were extended to Løkken Verk in 1910. [4]

The Urskog–Høland Line (Norwegian: Urskog–Hølandsbanen), also known as Tertitten, is a narrow gauge (750 mm (2 ft 5 1⁄2 in)) railway between Sørumsand and Skulerud in Norway. [5]

The Setesdal Line (Norwegian: Setesdalsbanen) was a railway between Kristiansand and Byglandsfjord in southern Norway, 78 km (48 mi) long. It was built with a narrow gauge of 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in), and opened to Hægeland 26 November 1895, and to Byglandsfjord 27 November 1896. Stations along the line included Mosby, Vennesla, Grovene (Grovane), Iveland and Hægeland. Now, 8km of this line is open as a heritage railway. [6]

By the 21st century, of the operational (non-heritage) railways in Norway, only the Trondheim (Trondhjem) Tramway has a different gauge, the metre-gauge, 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in). [2]

Returning to Speight’s article in The Railway Magazine, he refers his readers to a government publication in French and Norwegian which provided excellent statistical information and maps/plans – De Offentlige Jernbaner, Aschehoug & Co., Christiania. This appears to have been a regular, annual, publication and copies from later years can be purchased online. [8]

Speight focus was on describing his own experiences on the rail network in Norway. He entered Norway from Sweden on a train which ran direct from Helsingborg (in Sweden) to Christiania (Oslo) remarking on the spaciousness and comfort of the Norsk-Svensk hurtugtog, or fast train.

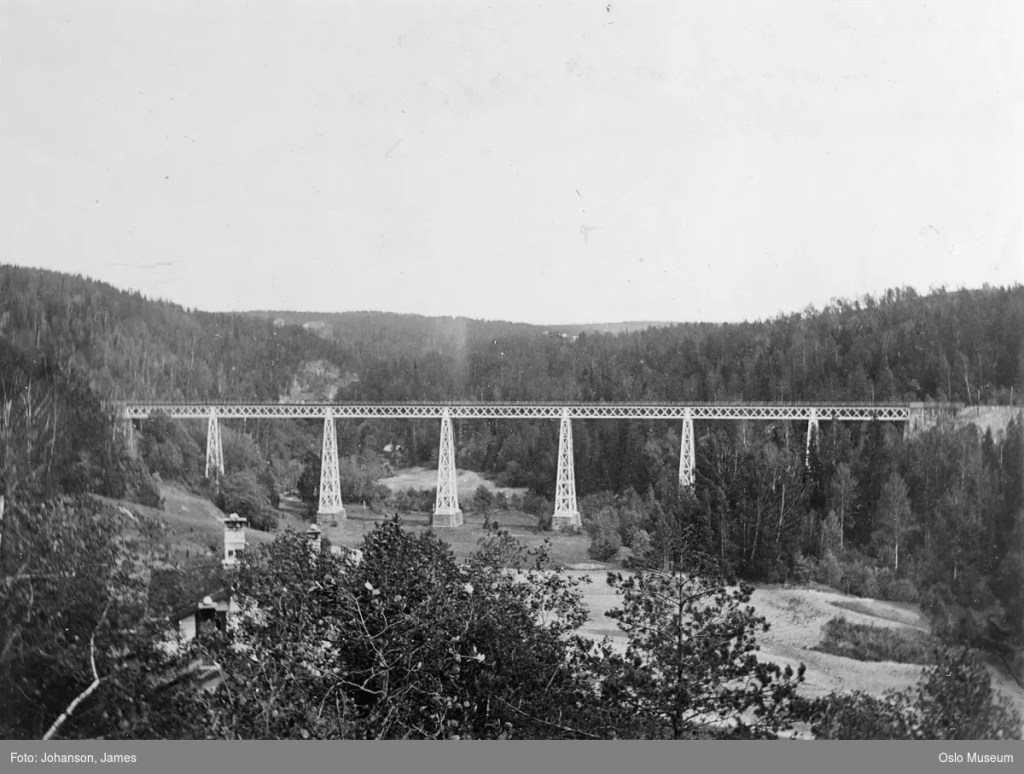

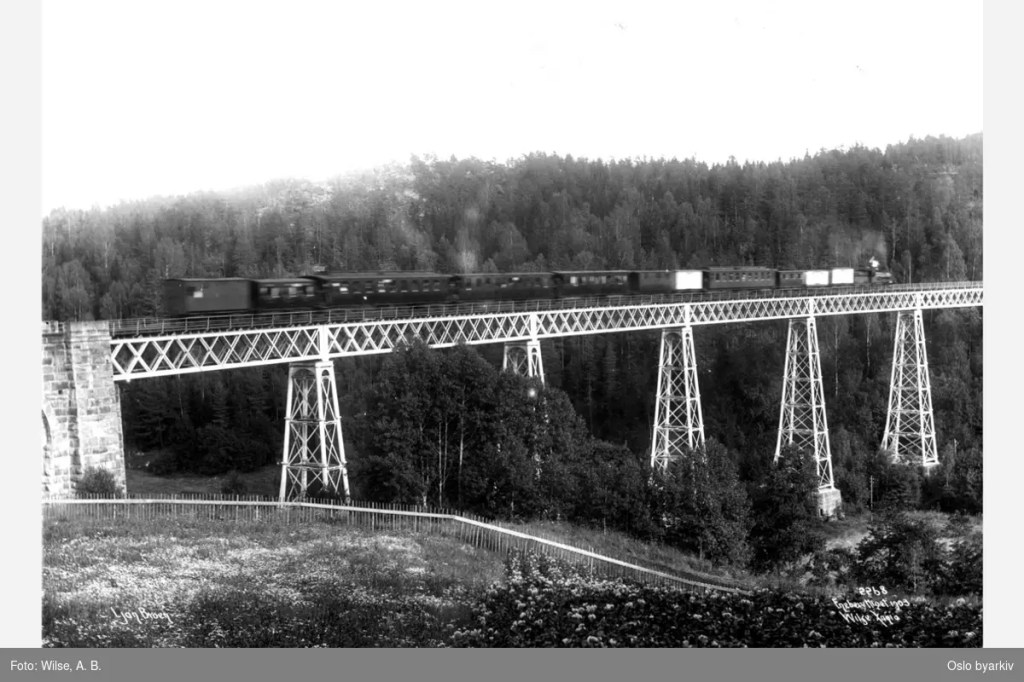

His first sight when opening the curtains of his train compartment in the morning was drizzle at the station in Frederikstadt. His first rail with rail journey in Norway was travelled at a very slow pace with long waits at stations in the route to Christiania (Oslo). He comments on the dramatic scenery and on the difficulties which must have been experienced in building the line on which he was travelling. Speight points his readers to the illustration below, which shows the Ljans viaduct (admittedly the photo quality is poor) and he says: “The train winds in and out among rocks and trees and over many a gorge, passing the most picturesque little wooden homesteads all the way from Ljan, a few miles out of the city. One of the pretty villas was a smoking ruin as we passed, and the conductor told me that the day before it was all right, and that such fires were a common occurrence. At the upper window of another of these wooden villas, standing just over the water of an inlet of the fjord, appeared two faces, and the conductor cheerily saluted his wife and little child, as he does three times each week on his return from Sweden.” [1: p449]

The three photographs immediately above are further photos of Ljans Viaduct taken before 1929 all of which are in the collection of the Norsk Jernbarnemuseum. [9]

Speight continues: the main station in Oslo “adjoins the quays, and is at the bottom of the main street which runs up past the chief shops to the Castle, Carl Johan’s Gade, or Johan as it is known all over Norway.” [1: p449]

The trip from Copenhagen to Christiania (Oslo) was advertised as an 18 hour or a 22 hour journey. In Speight’s view, the journey could have been completed in either 12 or 14 hours. The causes for the length of the journey, in Speight’s view were “the length and weight of the trains, the frequent long stops and the form of locomotive used. … They [were] manifestly incapable of taking the eight or ten corridor carriages over the gradients on this line. … The [then] present total of stopping time amount[ed] to about three hours; this [was] partly accounted for by the fact that meals [were] taken in the stations, and at the customs station a long stay [was] made. But there [was] no need for the five or ten minutes’ stops made at many of the small stations where the little business could [have been done] in a quarter of the time. If the two Governments cared to run … an express, from Helsingborg, stopping only, say, at Halmstad, Gothenburg, Trollhättan, Frederikshald, Frederik stadt and Moss (running a steamer thence to Horten for quick connection with Skein and Drammen) the journey should [have been completed] in 12 hours, the more easily if a restaurant car were [to be] attached to save long stops.” [1: p450]

Speight then travelled Southwest from Oslo along the line which had termini in Skein, Kroderen and Kongsberg. He complains that no first class carriages were provided on the line and comments again about the slow speed of the service despite expresses being provided. He says: “An approach is made towards running expresses, four trains daily passing between Christiania and Drammen, 33 miles, without a stop, but with an occasional crawl, in an hour and a half. There are obstacles to fast speed on this line also, as there are many crossings and such gradients that for the heavy trains it is necessary to have a small engine at each end The point of depar ture in Christiania is situated by Piperviken, a quay for coast steamers. Vestbanens station is smaller than the Eastern station, but none the less cold and uncomfortable. There is no refreshment room, and some of the less known Midland stations, say Bingley or Keighley, are palaces in comparison. The trains, however, are comfortable, being provided with through passages, open to the public, and irregularly disposed seats – some like an English tram car, others saloon fashion.” [1: p450]

Speight has only praise for the scenery on the line: “The scenery along the line is remarkably attractive. Inland, after leaving the western bights of Christiania fjord, the road is cut through many pretty bits of English scenery, and at busy, timber-laden Drammen the sea again appears. It is near Holmestrand, however, that a typical form of Norwegian railway is traversed, where high speed is manifestly impossible. On one side are cliffs, pine-clad and bird-haunted; on the other, beating against a low sea-wall, the water of the fjord. Holmestrand is a little seaside resort which is becoming very popular. The railway here runs close under the cliffs, and the town spreads on the narrow steep between the line and the beach. Down to Tönsberg, a viking town of lost glory, the train is backed, to be run out after a short stay on to the main line again, a proceeding which would have been unnecessary had the station been built some half-mile from the present one. The district between Tönsberg and Laurvik is meadow and shrubby rockland, abounding in ancient memories of rich plundering days. In one field near the railway is the famous Gokstad mound, whence, some years back, the large viking ship was taken which now stands in the University Museum at Christiania.” [1: p451]

“At Sandefjord, one of the most prettily situated towns in Norway, at the head of a four-mile fjord, with wooded rocky banks, [were] many signs of prosperity, and goods wagons are constantly to be seen in the sidings and down at the harbour, to which a branch line runs through the town. From here the line goes over the crest of the hill to Laurvik, a growing port, where passengers from Christiania for English ports are taken on board. Though the distance from Christiania is only 98 miles, the quickest train, the 11.17 p.m., takes 4 hr. 40 min. to make the journey, and one wretched “blandet-tog,” or mixed goods and passenger, actually spends 10 hr. 40 min. on the way. There is a morning train from Laurvik to Christiania which takes 11 hours, being passed on the way by another. Those who are unfortunate enough to be reduced to riding in one of these mixed trains have a dreadful time.” [1: p451]

This line, after leaving Laurvik, passes through Porsgrund, famous for its porcelain, and ends at Skien, a thriving manufacturing town.

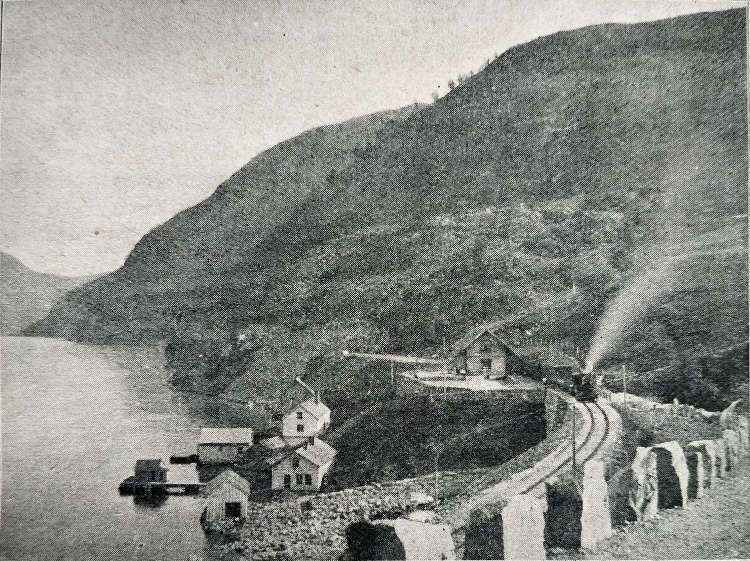

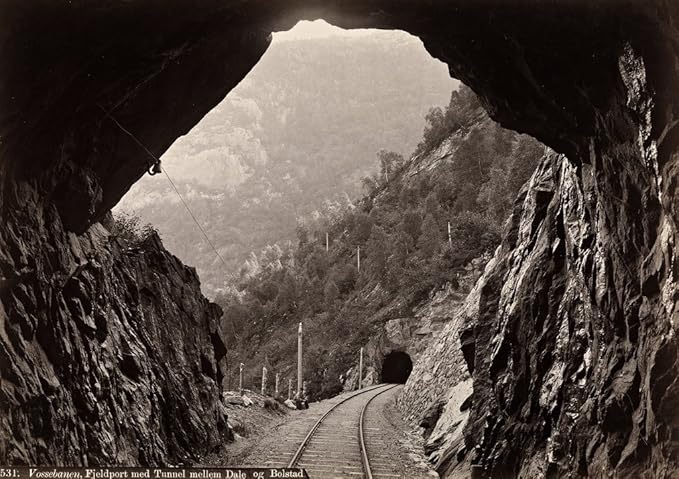

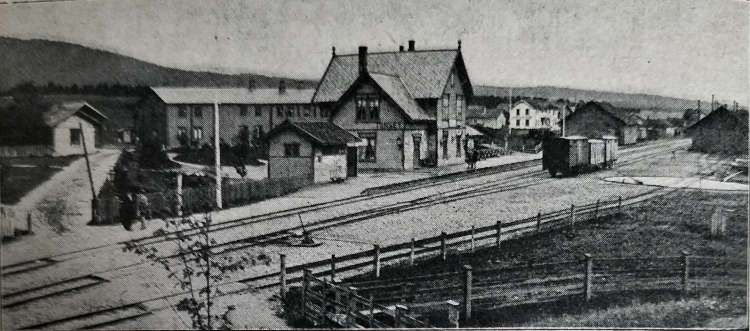

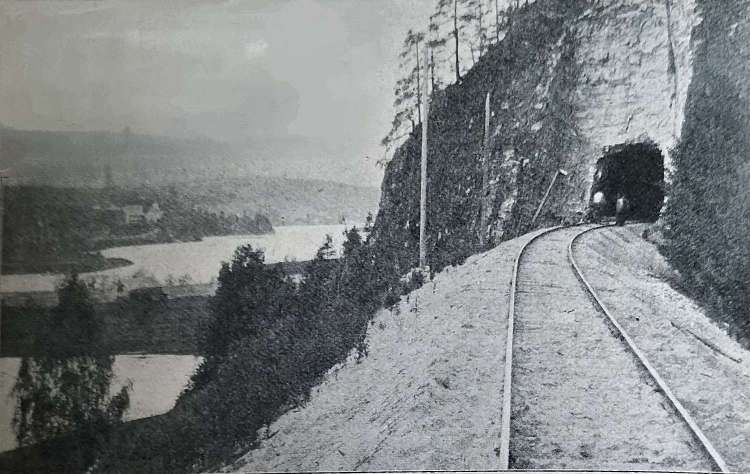

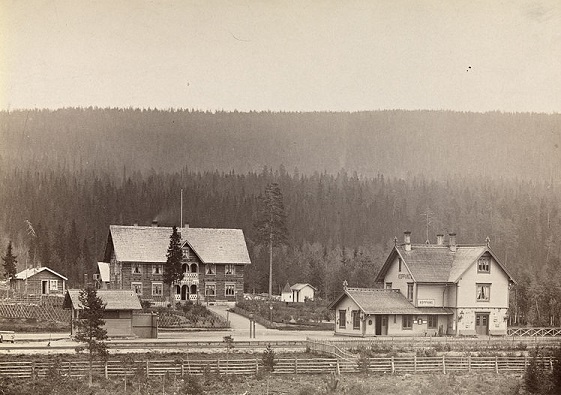

Speight was unable to travel over the lines which run from the coast inland, those from Christiansand to Byglandsfjord, Stavanger to Ekersund, and Bergen to Voss. He comments that the “two latter are perhaps too well known to English tourists to need description. … Two of the views accompanying this article (Trangereid Station and the mountain tunnel between Dale and Bolstad) will remind visitors to Bergen of the marvellous manner in which the engineering difficulties along the Vossebanen have been overcome.” [1: p451]

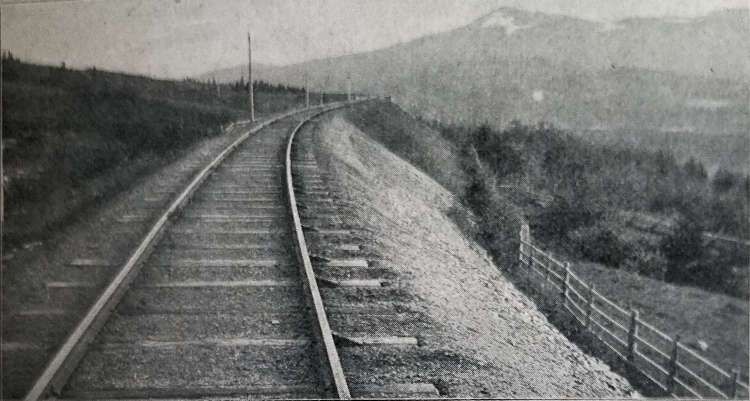

Speight now turns from the smaller lines in Norway to what was known as the trunk line to the North, “a line which by the very nature of the country it passes through must always attract the attention of those who are “railway mad.” Its seclusion and remoteness from the general tourist-route, added to the fact that from the map it appears to traverse a most romantic part of the country, stealing through the mountains, like the Midland line from Settle to the North, lends an air of mystery.” [1: p451-452]

From Oslo (Christiania), the train leaves “the large station by the docks at 1.45pm and runs to Eidsvold and over an inlet of Lake Mjosen into Hamar (on that section of the line built originally by an English company, and called Hovedbanen) steadily at 26 miles per hour, through meadow, wood, and lakeside scenery. At Hamar a change of trains is made, and all the passengers rush into the refreshment-room for ‘mid-dag’, an abundant meal of three courses, which costs about two shillings. Ample warning is given, and then you take places in a most comfortable corridor-train which seats and sleeps two persons only in each first-class compartment, a convenience which makes the journey no hardship, and which is regulated from the booking-office in Christiania. After leaving Hamar the pace is slow but very steady, and one’s attention is wholly occupied by the view from the windows. Fairly level country is passed through until Elverum, twenty miles from Hamar, then begins a slow climb, which lasts for eight hours. Elverum is 608 feet above the sea, and Tyvold, the highest point on the line, which is passed about two in the morning, 2,158 feet.” [1: p453]

The line climbs alongside the River Glomen for 150 miles, alternately on one bank then the other, until “settling down to a regular position east of the stream, under steep wooded cliffs. The river was filled with timber floating down from the mountains. … Across the valley which grew narrower hourly were mountain-ridges, whose summits were white with snow. Under them nestled farms the whole way, though their share of sunlight and warmth seemed to be small. Here and there would appear clusters of prosperous looking farmsteads, with telephone lines running from one to another. And all the while the long train was slowly making its way up through cuttings and tiny rock tunnels, along sandy strips of road among the fragrant pines.” [1: p453-454]

Speight continues: “Koppang was the supper-place, where we had twelve minutes to drink milk and eat smörbröd, i.e., sandwiches of bread and fish, cheese, or meat. After leaving this station the conductor began to prepare the beds, and when they were ready they were indeed cosy. Sleep came easily after the mountain air, and although the intervening grades of the slope were missed, this only heightened the surprise with which I looked out of the window after suddenly waking at two o’clock. The scenery had changed entirely. We were running along the side of a bare, wintry ridge, and the next minute passed gingerly over a roaring torrent. It was light, as the June nights are in Norway, and … everything was covered with snow, altogether such a view as one might get among the upper heights of Craven in winter. I had missed Röros, the high mining town, which I specially had hoped to see, but it was gratifying to have returned to consciousness just at the very highest point of the line.” [1: p454]

It took five hours to drop 2,100ft to sea-level at Trondhjem, “here everything was cold and desolate, and all the barns were dripping. … At Stören, reached [at] about five, the conductor brought us coffee and biscuits from the refreshment room. … From Stören we ran the 33 miles into Trondhjem in an hour and a half … and at 6.55 am, the train drew up alongside the harbour, where in old days the Hansa ships docked.” [1: p454-455]

“The line beyond Trondhjem … runs over the mountains into Sweden, … it provides one of the most fascinating railway journeys possible. … From Trondhjem the line runs along the bends of the fjord for many miles, turning finally inland at a place called Hell. … Then we enter Stördal, a narrow valley much resembling Upper Wharfdale, but with higher fells on each side and steeper falls of water coming down through the trees. For thirty miles the train creeps along into the heart of the mountains, past isolated farms, and always near the river, for the valley is only a few yards wide in places. The cart-road is grass-grown and one can see that the railroad is responsible for most of the traffic. Time after time one seems to be running straight into the hills; then a bend is turned and another mile or so of valley appears, with wonderful variety of forest and mountain views.” [1: p455]

When the train arrived at Gudaan a locomotive was attached behind, and then the train was pushed and pulled up through the otherwise bleak and desolate forest. Speight continues: “So well do we climb that in one hour we have actually ascended 1,000 feet, and when we reach the Swedish frontier station, [Storlien], sixty-six miles from Trondhjem, we are over 2,000 feet above the sea, in a wilderness of deep snow, though it is already June.” [1: p455]

This laborious journey between Norway and Sweden was necessary because there was constant traffic between Sweden and Trondhjem and trains can be very heavy. Speight refers us to Samuel Laing, who, he says, “lived in this region about the year 1834, [and] dwells at some length on the trade route over into Sweden, traversed in winter by sleighs, the best railroad in the world, he says. His astonishment would have been worth recording had he been told that in time an actual railroad would penetrate these wilds of the Keel, and that comfortable, spacious carriages would daily find their way through those bleak woods.” [1: p455]

At Storlien, Speight, left Norway, continuing his journey into Sweden.

Early Locomotives in Norway

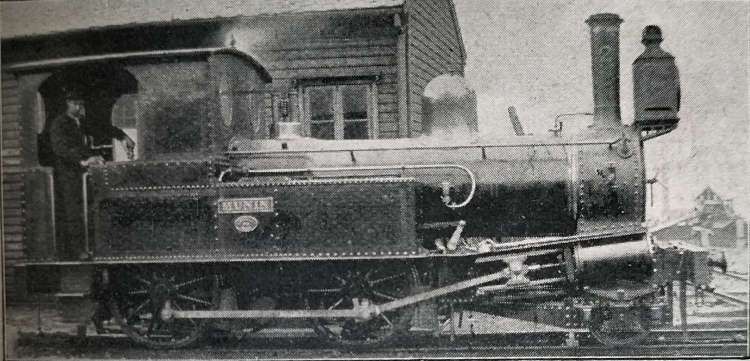

Speight commented on locomotives in Norway in 1899 seemingly being underpowered for the duties expected of them. He only provided one photograph of a locomotive in the article which is shown below. No details of the locomotive appears in his article. …

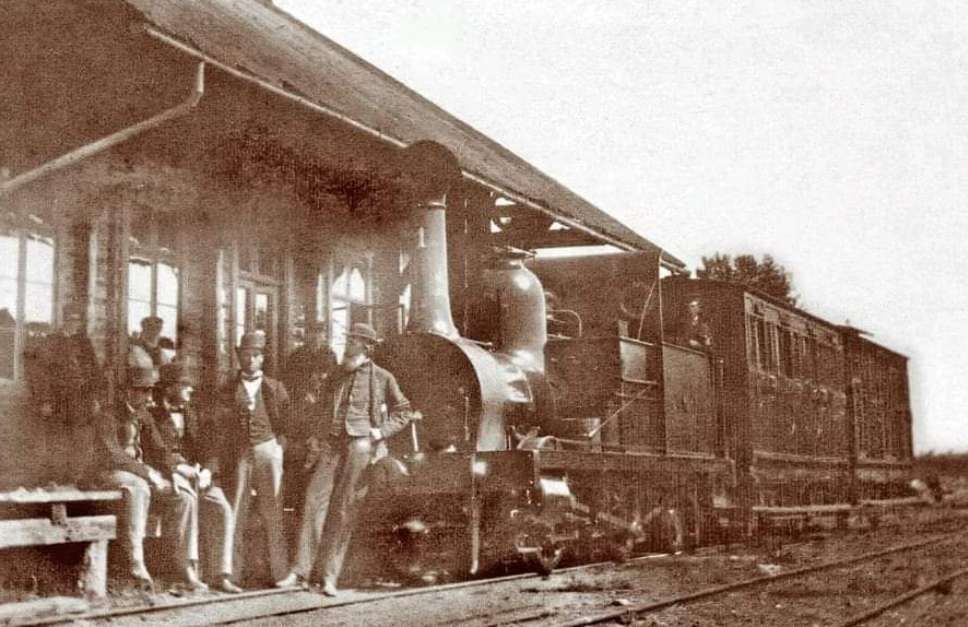

It seems as though Norway’s early narrow gauge steam locomotive classes were numbered using roman numerals by the NSB (I,II,III,IV,V, etc). [20] There is a limited amount of information available online about these locomotives, but it seems that a lot of the earliest classes were 2-4-0T locos. However, the first 3ft 6in gauge steam locomotive on Norway’s railways was an 0-4-2T, not a 2-4-0T but of a similar size to the other tank locomotives pictured above and further below. This 2-4-0T locomotive was No. 1 of the Hamar – Grundset Railway and is shown below at Løten station. The date was 18th October 1861, and it is believed that the photo was taken during a test run. Regular timetabled operations commenced on the railway the following month. The locomotive was built by Robert Stephenson & Co. in 1860. I found the photograph on transpressnz.blogspot.com. [25]

I have not been able to clarify which class of locomotive is pictures in E.E. Speight’s article. Similar sized locos are pictured below but all different in some way from E.E. Speight’s photograph – different cab, different dome, different chimney.

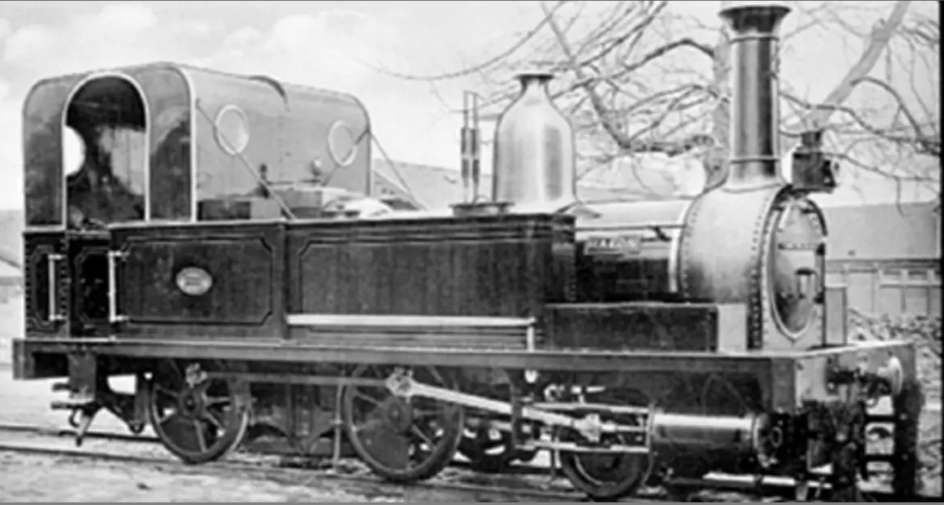

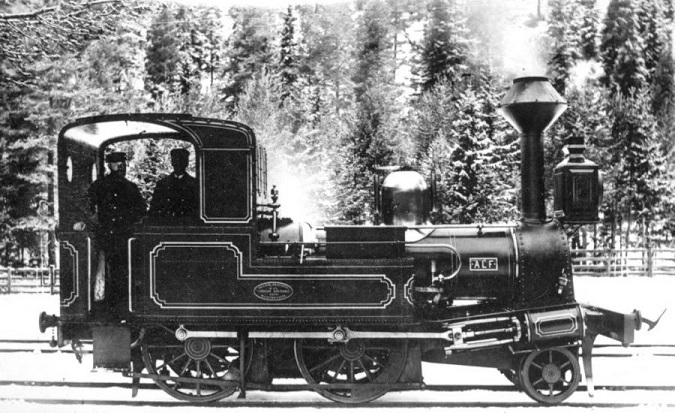

An example of the NSB Class II 2-4-0T side tank locos is shown below.

The NSB Class III locos were a class of six side tank 2-4-0T locomotives. They were built by Beyer, Peacock and company from 1868 to 1871 as part of the III class for the Norwegian State Railways. They were designed, built and operated for small local passenger trains for which they operated until the 1920s.

The NSB Class IV (or Tryggve Class) locos were 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) narrow gauge 2-4-0T steam locomotives built by Beyer, Peacock & Co. in Manchester, England. [21] This was a class of twenty-five side tank 2-4-0 locomotives. The first of the class was built by Beyer, Peacock and company in 1866 and the last built in 1882 also by Beyer, Peacock and company and originally classed II and XV from 1898. In 1900 the class was re-designated IV and IX and operated by the Norwegian State Railways until 1952 when the last one was withdrawn. The class was named Tryggve after the first locomotive of the class which was also numbered two. [23]

All these locomotives could well have been encountered by Speight on his journey through Norway.

References

- E.E. Speight; Through Norway by Rail; in The Railway Magazine, London, November 1899, p447-455.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rail_transport_in_Norway, accessed on 11th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narrow-gauge_railways_in_Norway, accessed on 11th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thamshavn_Line, accessed on 11th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urskog%E2%80%93H%C3%B8land_Line, accessed on 11th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Setesdal_Line, accessed on 11th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Abraham_Pihl, accessed on 11th September 2024.

- For example: De Offentlige Jernbaner: Driftsberetning For Norsk Hoved-jernbane … https://amzn.eu/d/5nfTiC5; and https://www.yumpu.com/no/document/read/19751486/de-offentlige-jernbaner-beretning-om-de-norske-jernbaners-drift-1-, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://www.skyscrapercity.com/threads/norway-railways.935718/page-9, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://www.banenor.no/en/traffic-and-travel/railway-stations/-t-/trengereid, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://www.amazon.co.uk/POSTER-Vossebanen-Fjeldport-Bolstad-replica/dp/B00P5I624K, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://no.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fil:528._Vossebanen,_fjeldport_med_Tunnel_mellem_Dale_og_Bolstad_-_no-nb_digifoto_20151106_00106_bldsa_AL0528_(cropped).jpg, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://jenikirbyhistory.getarchive.net/topics/rail+tunnels+in+vestland/historical+images+of+vaksdal, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tynset_%28novel%29#/media/File:7040_Tynset_Station_-_no-nb_digifoto_20150807_00223_bldsa_PK29688.jpg, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://help.g2rail.com/stations/tynset, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7c/Koppang_stasjon.jpeg/1280px-Koppang_stasjon.jpeg, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://www.banenor.no/en/traffic-and-travel/railway-stations/-k-/koppang, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Storen_stasjon_Rorosbanen_2008.JPG, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://jenikirbyhistory.getarchive.net/media/storlien-station-3b47b4, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norwegian_State_Railways_rolling_stock, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NSB_Class_IV, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://locomotive.fandom.com/wiki/NSB_Class_III, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://locomotive.fandom.com/wiki/NSR_IV_%22Tryggve%22_Class, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://digitaltmuseum.no/search/?aq=classification:%22RU%22,%225288%22, accessed on 12th September 2024.

- https://transpressnz.blogspot.com/2024/07/norwegian-0-4-2t-from-1860.html?m=1, accessed on 12th September 2024.