The Line of the West Clare Railway from Lahinch to Miltown-Malbay

We recommence our journey at Lahinch Station. The satellite image below was provided close to the end of the last post in this series. This satellite image allows the whole of the Lahinch area to be included. The area in the curved red box in the station area and is represented below in a sketch plan.

This satellite image allows the whole of the Lahinch area to be included. The area in the curved red box in the station area and is represented below in a sketch plan. Lahinch Station. [1]

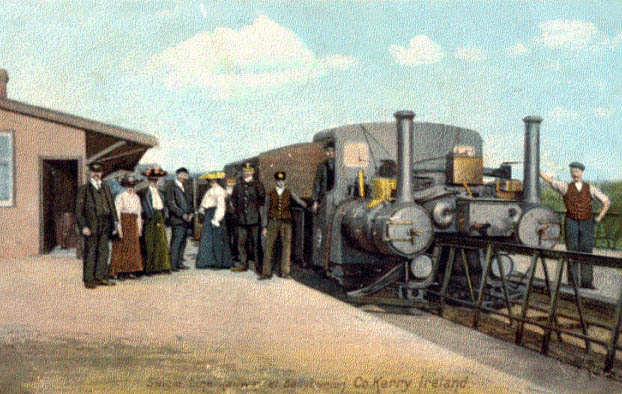

Lahinch Station. [1] Lahinch Station around the turn of the 20th Century, with the village beyond. [2]

Lahinch Station around the turn of the 20th Century, with the village beyond. [2] A train from Kilkee waits at Lahinch on its way to Ennis. [5]

A train from Kilkee waits at Lahinch on its way to Ennis. [5] Lahinch Station in 1961. [2]

Lahinch Station in 1961. [2]

As the above pictures show Lahinch Station developed over the years.

Lahinch or Lehinch (Irish: An Leacht or Irish: Leacht Uí Chonchubhair, meaning “The Memorial cairn of O’Connor”) is a small town on Liscannor Bay, on the northwest coast of County Clare, Ireland. It lies on the N67 national secondary road, between Milltown Malbay and Ennistymon, roughly 75 kilometres (47 mi) by road southwest of Galway and 68 kilometres (42 mi) northwest of Limerick. [4]

The town became a popular tourist destination on the Atlantic coast and close to the Cliffs of Moher. The Cliffs of Moher. [6]

The Cliffs of Moher. [6]

Lahinch developed from having just a few cabins in the eighteenth century to having a population of over one thousand people in 1835. However, no significant development took place in the early nineteenth century as the sea front continued to take a severe battering from the Atlantic gales. [3] It was not until later in the century that the infrastructure of the town developed and it became a seaside resort following the opening of the West Clare Railway in 1887. In 1883, the town was struck by a severe storm which destroyed the sea wall and promenade and damaged many buildings. Local governor William Edward Ellis oversaw the repair work which followed and the construction of a new sea wall and promenade were inaugurated by the wife of the Viceroy, Lady Aberdeen, in July 1893. [14]

Lahinch’s popularity and fame depend on two features. First and foremost is the mile-long beach of golden sand stretching along in front of the village, promenade and sandhills. With the growing popularity of sea bathing and the arrival of the West Clare Railway in 1887, people began to arrive in unprecedented numbers. The village’s secondary claim to popularity is its Golf Club. [3]

There was a short ascent out of Lahinch, 1 in 193, across Gregg level crossing, just beyond Mile Post 21 and through Coffey’s Bridge (No. 41) which carried a laneway over the line. With Moy Bay on the west the line crossed over the Lahinch-Miltown Road twice, first at Major’s Bridge (No. 42) and secondly at Crag Bridge (No. 43).

There was a short ascent out of Lahinch, 1 in 193, across Gregg level crossing, just beyond Mile Post 21 and through Coffey’s Bridge (No. 41) which carried a laneway over the line. With Moy Bay on the west the line crossed over the Lahinch-Miltown Road twice, first at Major’s Bridge (No. 42) and secondly at Crag Bridge (No. 43).

South of Lahinch Station the route described above is now hidden under new development as far as Major’s Bridge (or perhaps it is Crag Bridge). This bridge is the first evidence we can see of the route of the line South of Launch. It spans the modern N67 road.

The line was carried on an embankment to the South of Lahinch. Major’s Bridge (see below) has lost its superstructure but it was no doubt of very similar construction to the next structure which can be seen and the bottom of the adjacent satellite image, Crag Bridge (see below). [7]

The line was carried on an embankment to the South of Lahinch. Major’s Bridge (see below) has lost its superstructure but it was no doubt of very similar construction to the next structure which can be seen and the bottom of the adjacent satellite image, Crag Bridge (see below). [7]

Crag Bridge (see below) can be seen in the Google Streetview images below. The first picture is taken from the East looking towards the coast. The second photograph is taken from the West looking back along the N67 towards Lahinch.

In both these images the bridge is far more overgrown than it would ever have been while in use before the closure of the railway line.

Patrick Taylor’s choice of names for these two bridges [7] is unlikely to be correct. Edmund Lenihan suggests that the first bridge encountered is Crag Bridge and the second, Major’s Bridge. He comments: “Quite unexpectedly we were at Crag Bridge – or rather, where it had been, for the metal deck which spanned the Milltown road is one of two that have been removed. Before climbing down to the road, we paused for another look at the panorama stretching away southward. The line, embanked all the way, loops off to the southeast like some monstrous snake on its way towards the rugged scenic area known as ‘The Major’s Wood, beyond which the ground rises into the dark ridge of Black Hill, following the coast into the distance towards Rineen.” [8]

Patrick Taylor’s choice of names for these two bridges [7] is unlikely to be correct. Edmund Lenihan suggests that the first bridge encountered is Crag Bridge and the second, Major’s Bridge. He comments: “Quite unexpectedly we were at Crag Bridge – or rather, where it had been, for the metal deck which spanned the Milltown road is one of two that have been removed. Before climbing down to the road, we paused for another look at the panorama stretching away southward. The line, embanked all the way, loops off to the southeast like some monstrous snake on its way towards the rugged scenic area known as ‘The Major’s Wood, beyond which the ground rises into the dark ridge of Black Hill, following the coast into the distance towards Rineen.” [8]

In the North Clare Bridge Survey, the second bridge is recorded as Calluragh South Bridge as below. It’s proximity to Moy House suggests that this much have been Major’s Bridge. [11] This length of the line was exposed to the strongest Atlantic weather. So exposed that it was the scene of a derailment on 24th December 1912, caused by a freak wind. [7] Edmund Lenihan, writing in the late 1980s, says: The sizeable cutting which succeeds this long clear stretch has only one claim to fame, so far as I am aware. Here, on a (lay of fierce storm almost eighty years ago, several carriages of an unladen special from Kilrush were derailed — literally blown off the track. [12]

This length of the line was exposed to the strongest Atlantic weather. So exposed that it was the scene of a derailment on 24th December 1912, caused by a freak wind. [7] Edmund Lenihan, writing in the late 1980s, says: The sizeable cutting which succeeds this long clear stretch has only one claim to fame, so far as I am aware. Here, on a (lay of fierce storm almost eighty years ago, several carriages of an unladen special from Kilrush were derailed — literally blown off the track. [12]

That cutting included Major’s Road Bridge and Major’s River Bridge over the River Moy. Edmund Lenihan comments: “Moy House, white and turreted, [is] situated on rising scenic ground overlooking the coast just west of the Moy River. Built by the Fitzgeralds, landlords of the area, in the early nineteenth century, it was later bought by Major George Studdert, whose descendants lived in it until the 1930s. He lent his title to the fine railway bridge which crosses the river a short distance away. Even yet it is known as `The Major’s Bridge’ and is, with Toloughlahan and Cullenagh, one of those that should be preserved for posterity. The view from it is spectacular. The public road dips into the wooded valley of the Moy River here, and the coincidence of road and rail bridges only yards apart makes this a memorable place.” [12]

Sadly the wooded valley of the River Moy is now choked with blackthorn and the river bridge is, in the 21st Century, seemingly inaccessible. Moy House is now a Georgian country house hotel about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) south of Lahinch near the village of Moy. Originally set in 15 acres of woodland on the River Moy, it was built in the mid-18th century as the holiday home of Sir Augustine Fitzgerald. Later it was sold to Major Studdert, who gave his name to the bridges over the road and the river on the West Clare. The house was vacant for 10 years, but was purchased by Antoin O’Looney who undertook a three year restoration of the property. It was voted Country House of the Year by Georgina Campbell’s Ireland in 2003. [9][10]

Moy House is now a Georgian country house hotel about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) south of Lahinch near the village of Moy. Originally set in 15 acres of woodland on the River Moy, it was built in the mid-18th century as the holiday home of Sir Augustine Fitzgerald. Later it was sold to Major Studdert, who gave his name to the bridges over the road and the river on the West Clare. The house was vacant for 10 years, but was purchased by Antoin O’Looney who undertook a three year restoration of the property. It was voted Country House of the Year by Georgina Campbell’s Ireland in 2003. [9][10] Moy House from the sea. [10]

Moy House from the sea. [10]

South of the second bridge, the line crosses the Moy River and curves slightly to the East before swinging gradually round to the West. The adjacent satellite image and the one directly below show the route.

South of the second bridge, the line crosses the Moy River and curves slightly to the East before swinging gradually round to the West. The adjacent satellite image and the one directly below show the route.

The location of the Moy River Bridge was adjacent to Major’s Road Bridge. The picture above shows that the river bridge is amidst heavy blackthorn growth.

Both the road and the railway followed the line of least resistance as they climbed to cross Black Hill, travelling first along its flank and heading towards the sea.

Edmund Lenihan found the ground along the route from the river to Moy Bridge almost impassible in the 1980s.

Moy Bridge another structure to have had its steel/wrought-iron deck removed. Headroom was no doubt the issue here. Edmund Lenihan says: “The metal deck of Moy Bridge, like the one at Crag, has been removed. Only the stone abutments remain. The reason probably is that it was a particularly low structure, with headroom of no more than 10 feet — hardly high enough to let modern cattle trucks pass. This was also known as Hanrahan’s Bridge, and was made a halt in October 1958 — the last halt, in fact, to be instituted before the closure of the system.” [13]

Moy Bridge another structure to have had its steel/wrought-iron deck removed. Headroom was no doubt the issue here. Edmund Lenihan says: “The metal deck of Moy Bridge, like the one at Crag, has been removed. Only the stone abutments remain. The reason probably is that it was a particularly low structure, with headroom of no more than 10 feet — hardly high enough to let modern cattle trucks pass. This was also known as Hanrahan’s Bridge, and was made a halt in October 1958 — the last halt, in fact, to be instituted before the closure of the system.” [13]

From Moy Bridge Lenihan talks of the line turning southwestward “more or less paralleling the Miltown road at a distance of never more than 500 yards for the next mile or more, until they swing together again halfway to Rineen school house, whence they curve round the western edge of Drummin Hill and on south to Miltown.” [13] The picture below is taken from Google Streetview and shows the line of the West Clare at the location of the first road (to the right of the image) shown on this satellite image.

The picture below is taken from Google Streetview and shows the line of the West Clare at the location of the first road (to the right of the image) shown on this satellite image. Miltown is a mere 2 miles from here, but there is still much to encounter on the route of the railway before Miltown is encountered. Edmund Lenihan again: “We left Moy Bridge behind, and framed by the V of the cutting beyond lay the wood we had seen from Crag Bridge as a mere smudge along the side of the hill. As we came closer we saw why it is called the Black Hill: the ‘wood’ consists almost wholly of blackthorn, flattened into the steep hillside by the sea wind, thereby giving the impression of a solid mass. The visual effect created at this time of bare branches is startling. As we passed into the townland of Moybeg, the line had almost swung under the hill, and the distance between us and the wood continued to narrow. It is rough land and very neglected-looking. Water, more than anything else, impresses itself on the eye and ear: sodden fields left and right, a hidden cascade tumbling down somewhere through the wood, and the bay off to the west beyond the road. It is no place for the fainthearted traveller. Where line and wood eventually met we found our way barred by a stout fence and beyond that a jungle. We were soon floundering in bog and marsh.” [15]

Miltown is a mere 2 miles from here, but there is still much to encounter on the route of the railway before Miltown is encountered. Edmund Lenihan again: “We left Moy Bridge behind, and framed by the V of the cutting beyond lay the wood we had seen from Crag Bridge as a mere smudge along the side of the hill. As we came closer we saw why it is called the Black Hill: the ‘wood’ consists almost wholly of blackthorn, flattened into the steep hillside by the sea wind, thereby giving the impression of a solid mass. The visual effect created at this time of bare branches is startling. As we passed into the townland of Moybeg, the line had almost swung under the hill, and the distance between us and the wood continued to narrow. It is rough land and very neglected-looking. Water, more than anything else, impresses itself on the eye and ear: sodden fields left and right, a hidden cascade tumbling down somewhere through the wood, and the bay off to the west beyond the road. It is no place for the fainthearted traveller. Where line and wood eventually met we found our way barred by a stout fence and beyond that a jungle. We were soon floundering in bog and marsh.” [15] The line follows the gentlest possible path rising seemingly gradually through the contours and as a result drifts back towards the line of the road as this 1940s OS Map shows. The grade was however really quite steep for the underpowered locomotives of the West Clare Railway.

The line follows the gentlest possible path rising seemingly gradually through the contours and as a result drifts back towards the line of the road as this 1940s OS Map shows. The grade was however really quite steep for the underpowered locomotives of the West Clare Railway.

Lenihan continues his late 1980s perambulation: “All this time the only constant thing was the hill, overlooking us severely to the left; the rest was a mixture of inaccessible thickets followed by the odd patch of reclaimed land. Among the stones at three different places we found chunks of yellow scorched brick and knew we were still on target. These were burned-out fire-bricks from the fire-boxes of the steam locomotives, dumped here with ash and other debris as packing for the sleepers.They were a useful guide to us on several occasions in ground that would have been otherwise featureless.” [16]

“When the line began to rise, it did so gradually at first over 500 yards or so, but then steeply. It is so straight and grown in by hazel up along the flank of the hill that we had to pause every so often in order to check our progress by looking through the branches, out towards the bay.” [17] The un-gated crossing on the minor road at the bottom left of this image is shown in the images below.

The un-gated crossing on the minor road at the bottom left of this image is shown in the images below.

The un-gated crossing close to the centre of this image is the site of the next picture looking forward along the line.

The un-gated crossing close to the centre of this image is the site of the next picture looking forward along the line.

Patrick Taylor’s comments about this length are more succinct than those of Edmund Lenihan: “At Mile Post 22.25 Hanrahan’s Bridge (No. 45) (or Moy Bridge in earlier days) became a railcar stopping place on 1st October 1958 (the last one created before closure). The line, already ascending at 1 in 96 steepens with sections of 1 in 63/64/55 and 52 up Rineen Bank on the flank of the Black Hill – a formidable climb in steam days. Moymore No. 1 and No. 2 level crossing were in this section – close together at Mile Post 23. and Rineen Halt was at m.p. 24.5, opened on 5th May 1952. A ballast siding was once in operation here and in the earlier days trains stopped on request. ” [7]

Patrick Taylor’s comments about this length are more succinct than those of Edmund Lenihan: “At Mile Post 22.25 Hanrahan’s Bridge (No. 45) (or Moy Bridge in earlier days) became a railcar stopping place on 1st October 1958 (the last one created before closure). The line, already ascending at 1 in 96 steepens with sections of 1 in 63/64/55 and 52 up Rineen Bank on the flank of the Black Hill – a formidable climb in steam days. Moymore No. 1 and No. 2 level crossing were in this section – close together at Mile Post 23. and Rineen Halt was at m.p. 24.5, opened on 5th May 1952. A ballast siding was once in operation here and in the earlier days trains stopped on request. ” [7] The road and railway ran immediately next to each other for some distance through Rinneen.

The road and railway ran immediately next to each other for some distance through Rinneen.

Again, Patrick Taylor comments: “The line continued by the side of Rineen Hill quite adjacent to the main Lahinch-Miltown public road. which ran parallel with the railway for three miles and at some points was only separated by a stone wall. On this stretch there were two bridges, Rineen over a stream, and Downes (No. 51) which crossed the line at Ballinaphonta, before Miltown-Malbay was reached at Mile Post 27.” [7]

Again, Patrick Taylor comments: “The line continued by the side of Rineen Hill quite adjacent to the main Lahinch-Miltown public road. which ran parallel with the railway for three miles and at some points was only separated by a stone wall. On this stretch there were two bridges, Rineen over a stream, and Downes (No. 51) which crossed the line at Ballinaphonta, before Miltown-Malbay was reached at Mile Post 27.” [7]

Lenihan takes us on towards Rineen: In the next mile or so, “to Rineen school, there is a dramatic improvement in the quality of the holdings and consequently far more houses. Most of them are just one field in from the road, which means that the railway ran by their front doors. Perhaps this is why, in May 1952, a halt was opened a few hundred yards to the Lahinch side of the school.” [18] Rineen Crossing and Halt in 1953, (c) IRRS. [18]

Rineen Crossing and Halt in 1953, (c) IRRS. [18]

“Across the road from the school is as good a place as any to get an accurate impression of the condition of the line. Look back – it is there; look forward – nothing. For as far as we were able to see all had been swept away. … Under Drummin Hill, which in places falls cliff-like to the road, railway and highway were separated by only a stone wall, a short way beyond where the 25th Mile Post was located.” [19]

Below the railway along this length is a small stone monument – a plaque commemorating the Rineen ambush, one of the best-known actions of the War of Independence in Clare.  From this hill, on 22nd September 1920, a party from the 4th battalion of the IRA attacked a truck bringing police from Miltown to Ennistymon. In the ensuing fight, which was soon joined by British reinforcements, six police were killed with no losses on the part of the attackers!

From this hill, on 22nd September 1920, a party from the 4th battalion of the IRA attacked a truck bringing police from Miltown to Ennistymon. In the ensuing fight, which was soon joined by British reinforcements, six police were killed with no losses on the part of the attackers!

The consequences for Lahinch, Miltown and Ennistymon were drastic. “Tne orgy of reprisals — burnings and shootings — released against them still remains vivid in the minds of old people. At 7 p.m that night the military invaded Miltown, burning, looting and smashing windows. In the small hours of the morning, when it seemed as if the worst was over, the Tans arrived from their depredations in Ennistymon and Lahinch, and joined by the local RIC they continued the arson, theft and shooting until the following morning. It was a night’s work that destroyed for ever any shreds of confidence that the people of Kilfarboy might have retained in the forces of the Crown.” [20]

The form/layout of the ambush is illustrated in the sketch plan above. [22]

The form/layout of the ambush is illustrated in the sketch plan above. [22]

Travelling on, the line has all but been obliterated beyond the Bridge at Rineen which is shown in a sketch (c) M. Lenihan in Lenihan’s book. [21] The North Clare Bridge Survey calls this bridge Drummin (Ibrikan) Bridge. [11]

The North Clare Bridge Survey calls this bridge Drummin (Ibrikan) Bridge. [11]

The same location, above, in a Google Streetview image from December 2009.

The same location, above, in a Google Streetview image from December 2009.

The momument is at location ‘1’ on the adjacent satellite image, the bridge is at location ‘2’.

The bridge, says Lenihan, is the “most elegant stone-arched crossing remaining on the line today. All its facings and the underside of the eye are of West Clare stone, but it is beginning to deteriorate, probably because of damage done by machines when the bank on its southern side was being cut away. It cannot survive long even in its present condition unless some restorative action is soon taken. [21]

As can be seen on this satellite image and the OS Map from the 1940s, a little way south of the bridge the road and railway separate.

As can be seen on this satellite image and the OS Map from the 1940s, a little way south of the bridge the road and railway separate.

It is very difficult to pick out the line of the railway on Google Earth and it appears to have been just as difficult to follow the line in the late 1980s. Edmund Lenihan comments that a very broken section followed: “with a filled-in cutting, a house built on the line and farm sheds surrounding a second cutting.” [23]

From here, it appears that the line ran in a straight line to Miltown Station. Lenihan says: “We emerged into not only the flat prospect of Fintramore but also an unexpected blaze of wintry sunshine. It cheered us, as did a clear view of the line for over half a mile, embanked all the way across the low bare fields. Off left, the spire of Miltown Church needled the sky, showing us how near we were to the terminus of the West Clare, while a bridge ahead served as a marker of our progress. Just beyond the location of the twenty-sixth milepost, a cattle-pass, 200 yards out, is still entirely intact [location ‘4’ below], but we had eyes only for the bridge [location ‘3’ above and below] and the view around.” [23] “At the bridge, [location ‘3’] we were a little surprised to find the metal deck still in place, but this is probably only because the road which runs underneath does not lead to anywhere of great significance and traffic is not heavy. Though in the town-land of Drummin, it was known as Rineen Bridge.” [23] It is shown below in its listing on the North Clare Bridge Survey. [11]

“At the bridge, [location ‘3’] we were a little surprised to find the metal deck still in place, but this is probably only because the road which runs underneath does not lead to anywhere of great significance and traffic is not heavy. Though in the town-land of Drummin, it was known as Rineen Bridge.” [23] It is shown below in its listing on the North Clare Bridge Survey. [11]

Looking back from location ‘5’ on the 1940s OS Map above, the embankment is visible in the distance under the red line showing the route of the railway. The record from the North Clare Bridge Survey below, shows the infilled bridge at location ‘5’. [11]

Looking back from location ‘5’ on the 1940s OS Map above, the embankment is visible in the distance under the red line showing the route of the railway. The record from the North Clare Bridge Survey below, shows the infilled bridge at location ‘5’. [11] The next image is taken from the single track road carried by Fintra More Bridge. The view looks South towards Miltown.

The next image is taken from the single track road carried by Fintra More Bridge. The view looks South towards Miltown.

The partially-filled cutting above clearly shows the line of the railway under the road bridge at location ‘5’. Miltown church spire can be seen on the horizon. Lenihan refers to this as Downes’ Bridge which he says is a “stone-arched span carrying a by-road over the line.” [23]

The partially-filled cutting above clearly shows the line of the railway under the road bridge at location ‘5’. Miltown church spire can be seen on the horizon. Lenihan refers to this as Downes’ Bridge which he says is a “stone-arched span carrying a by-road over the line.” [23]

South from this point the line crossed two streams and a cattle underpass before reaching another highway. Lenihan describes one of these valleys like this: “But now occurs one of those folds in the land which in extent are not large but which possess a beauty that has nothing to do with size alone. A small river flows here a full 25 feet below the level of the surrounding little hills, and it was this space that the builders of the line had to contrive a crossing for. That they succeeded admirably is unquestionable, and far from spoiling the beauty of this secluded place, their well-proportioned embankment and bridge lend it a light touch of order and symmetry. It is well worth a visit, though I suspect that few people know about it, near and all as it is to the town.” [23]

The satellite images provided by Google are relatively poor quality along this section of the line. The streams can only just be made out on the adjacent image. The highway is the erstwhile N67 which fled west from the line earlier in the journey. It is highlighted by the blue line on the satellite images – at the bottom left of the first and entering from the left on the second.

The route of the line either side of the N67 has been heavily built over. The properties built are all domestic dwellings. The OS Map from the 1940s shows road and railway crossing (below) at what appears to be an at-grade crossing rather than a bridge.

Pictures from the 21st Century seem to confirm this. The first photograph below looks back along the route of the line towards Lahinch. The private driveway is roughly along the line of the old railway.

The private house is what was once the old railway station of Miltown-Malbay. In the 21st century this has been refurbished as a home.

The station itself was on the North side of the N67. The second picture below takes a better look at the buildings and the old station canopy is clearly seen in the image. The view back towards Lahinch from the N67 in Miltown. The picture was taken from Google Streetview.

The view back towards Lahinch from the N67 in Miltown. The picture was taken from Google Streetview. The old station layout is clearer in this image. [25]

The old station layout is clearer in this image. [25] The station while still in use with the road which is now the N67 in the foreground with the crossing gates being opened to allow the passage of the railcar travelling South. The station track layout is also clear in this image and is reproduced as a sketch by Patrick Taylor below. [24]

The station while still in use with the road which is now the N67 in the foreground with the crossing gates being opened to allow the passage of the railcar travelling South. The station track layout is also clear in this image and is reproduced as a sketch by Patrick Taylor below. [24] The rail layout at Milotown Malbay. [1]

The rail layout at Milotown Malbay. [1]

We finish this part of the journey here in Miltown-Malbay.

References

- Patrick Taylor; The West Clare Railway; Plateway Press, 1994, p48.

- Edmund Lenihan; In the Tracks if the West Clare Railway; Mercier Press, Dec. 2008, p130-136.

- http://www.clarelibrary.ie/eolas/coclare/places/lahinch_history.htm, accessed on 15th April 2019.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lahinch, accessed on 17th April 2019.

- http://www.schmalspur-europa.at/schmalsp_87.htm, accessed on 17th April 2019.

- https://www.postcardsireland.com/postcard/cliffs-moher-lahinch-co-clare-1, accessed on 17th April 2019.

- Patrick Taylor; op.cit., p40.

- Edmund Lenihan; op.cit., p144.

- Georgina Campbell; Georgina Campbell’s Ireland, the Best of the Best: Ireland’s Very Best Places to Eat, Drink and Stay; Georgina Campbell Guides. 2005, p. 71, accessed on 19th April 2019.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moy_House, accessed on 19th April 2019.

- https://www.clarecoco.ie/services/arts-recreation/publications/north-clare-road-bridge-survey-2015-22291.pdf, accessed on 12th April 2019.

- Edmund Lenihan; op.cit., p145.

- Ibid., p147.

- http://www.clarelibrary.ie/eolas/coclare/places/lahinch_places_interest.htm, accessed on 19th April 2019.

- Edmund Lenihan; op.cit., p149.

- Ibid., p150.

- Ibid., p151.

- Ibid., p152-153.

- Ibid., p155.

- Ibid., p156-157.

- Ibid., p158.

- http://www.clarelibrary.ie/eolas/coclare/history/rineen.htm, accessed on 19th April 2019.

- Edmund Lenihan; op.cit., p159-160.

- Patrick Taylor; op.cit., p40.

- https://www.booking.com/hotel/ie/miltown-malbay-station-house-accommodation.html, accessed on 20th April 2019.

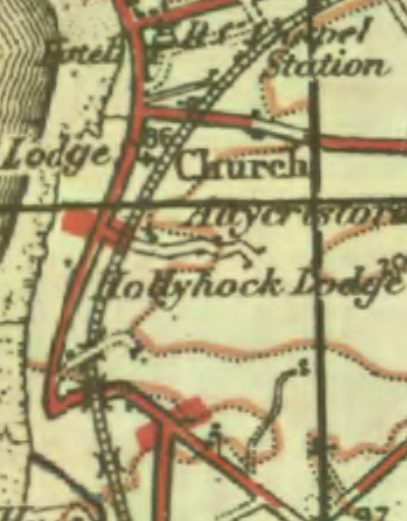

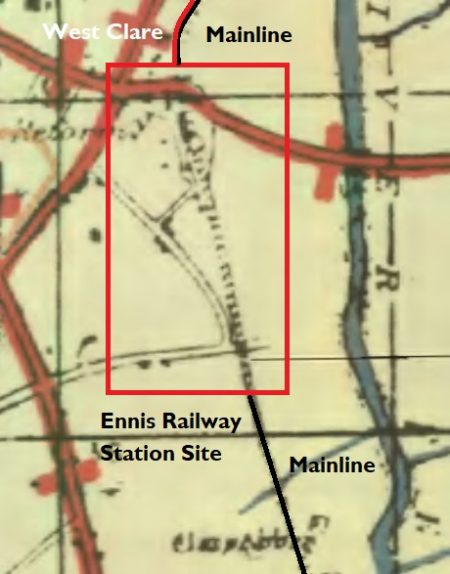

In the past it was also the terminus of the 3ft-gauge West Claire Railway which ran North from the station alongside the mainline. North of Quin Road the land is shown on the adjacent 1917 OS Map as being used by a rail-served sawmill.

In the past it was also the terminus of the 3ft-gauge West Claire Railway which ran North from the station alongside the mainline. North of Quin Road the land is shown on the adjacent 1917 OS Map as being used by a rail-served sawmill.

The extended crossing-keepers cottage is seen above from the Southwest in April 2009.

The extended crossing-keepers cottage is seen above from the Southwest in April 2009.