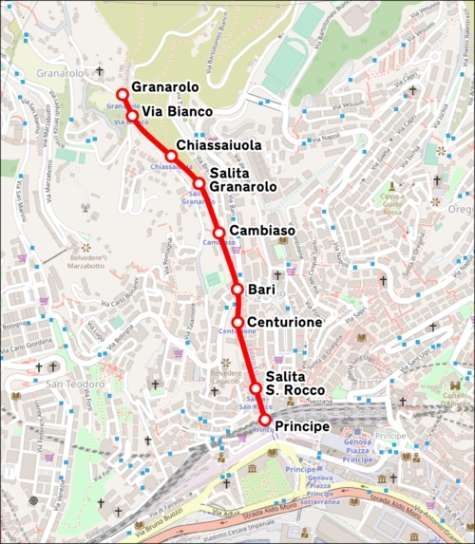

The Principe–Granarolo rack railway (Ferrovia Principe-Granarolo) is a rack railway that connects Via del Lagaccio, near the Genoa Piazza Principe railway station, to the Granarolo hills. The line is sometimes erroneously described as a funicular. The line is managed by AMT Genova, which manages the city’s public transport. [1]

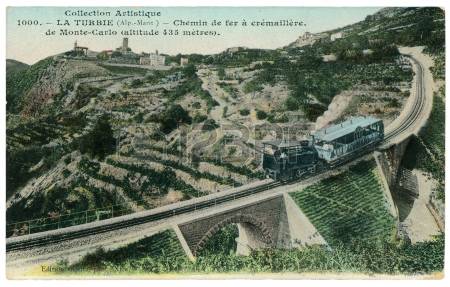

Work on the Principe–Granarolo rack railway started in 1898, and operation commenced in 1901. The line’s unusual track gauge and passing loop arrangement, both common in funiculars but rare elsewhere, have suggested to some that the line may have started life as a funicular and been converted to rack operation; however the line’s owners have dismissed this theory. [1][2][3]

The line’s cars were totally rebuilt in 1929, with new body and mechanical equipment, and the line was rebuilt in 1976. [1][3]

In 2002, Car 2 was sent away for an overhaul, but the bankruptcy of the original contractor and the involvement of a replacement in an alleged bribery scandal meant that the overhaul was not completed and the car returned to the line until March 2019. The overhaul included the replacement of the car floor, lighting, safety systems, electric drive, air conditioning and a new driver’s seat. Between 2002 and 2019, service was provided by Car 1 operating alone. AMT now plans to use the rebuilt car to double the service frequency to every 15 minutes. [1][4]

In November 2024, AMT Genova were undertaking significant maintenance work and the line was closed. On 8th November, they explained that the rack railway was “temporarily down due to an electrical problem with the motor of the upstream traction axle. The restoration activities have already started. Updates on the resumption of service will follow. … During rack downtime, the G1 replacement bus is active.” [5]

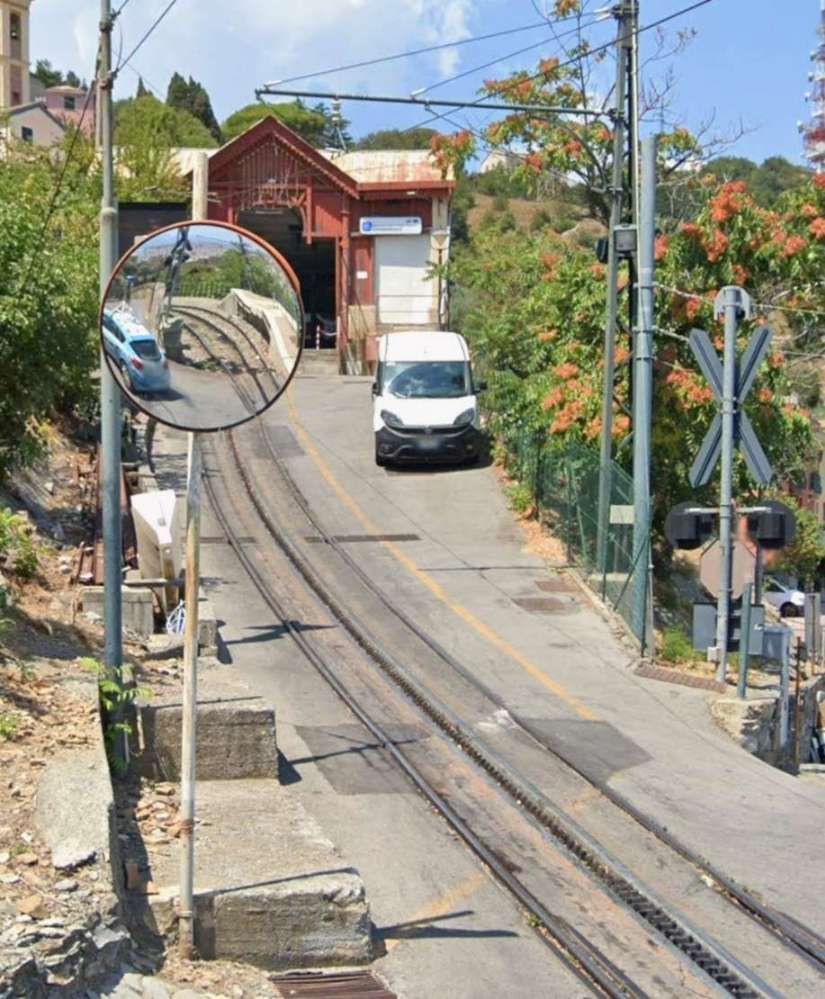

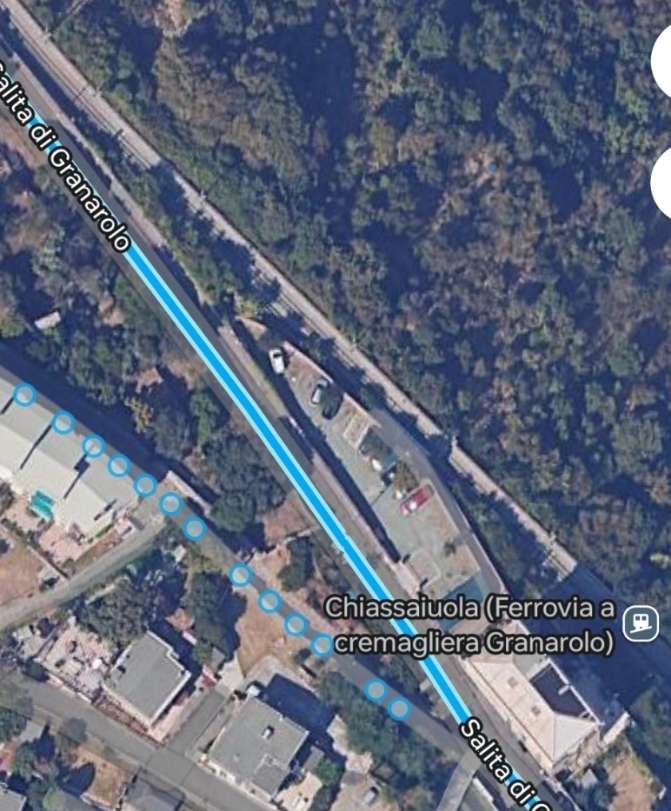

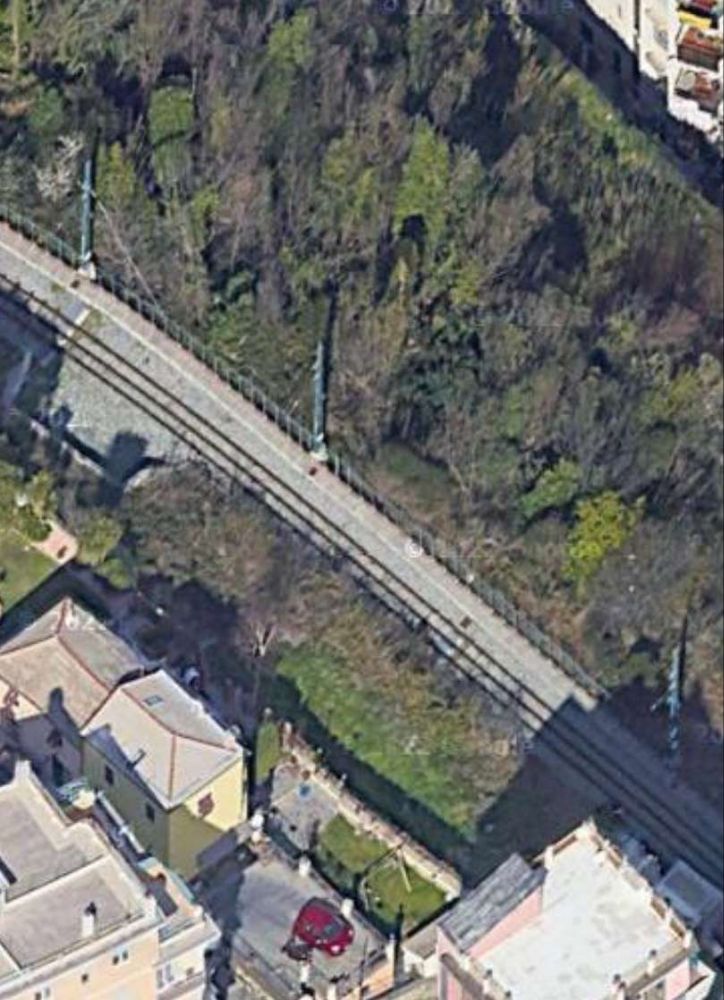

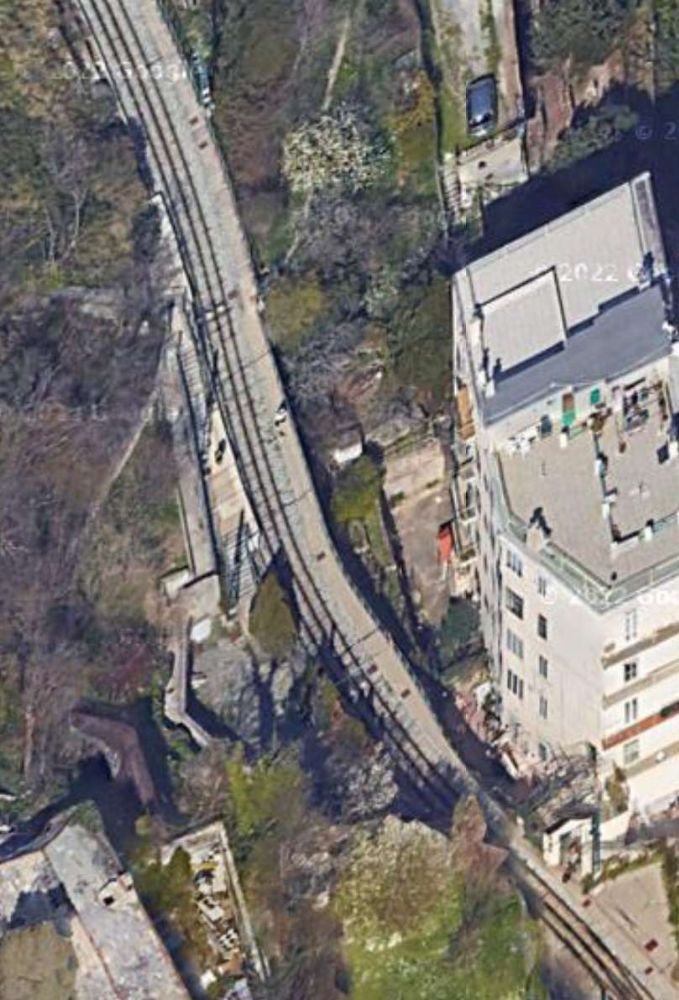

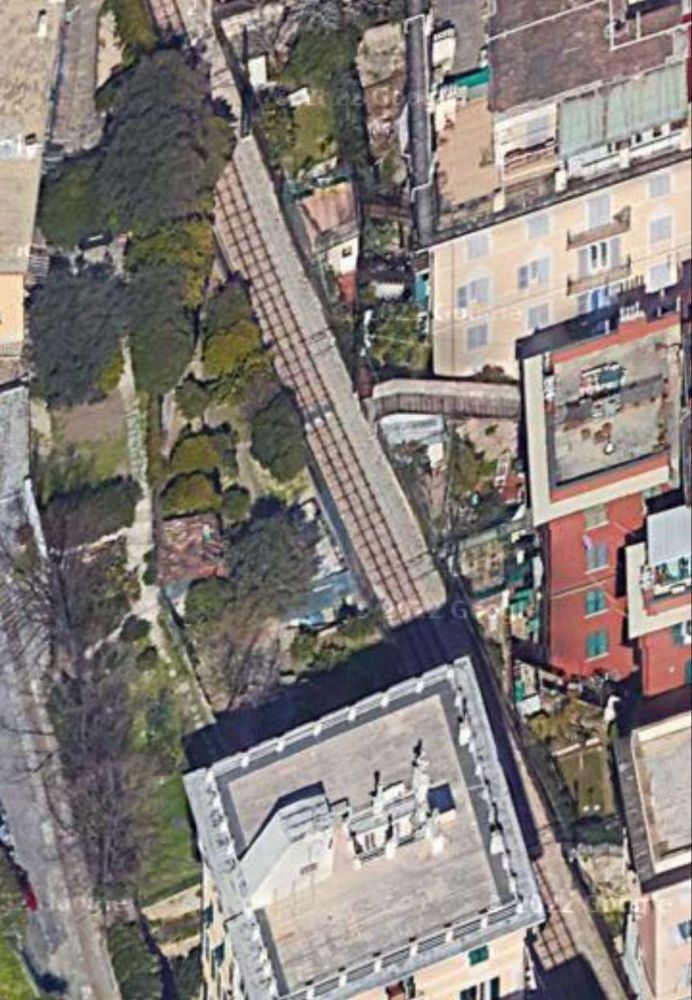

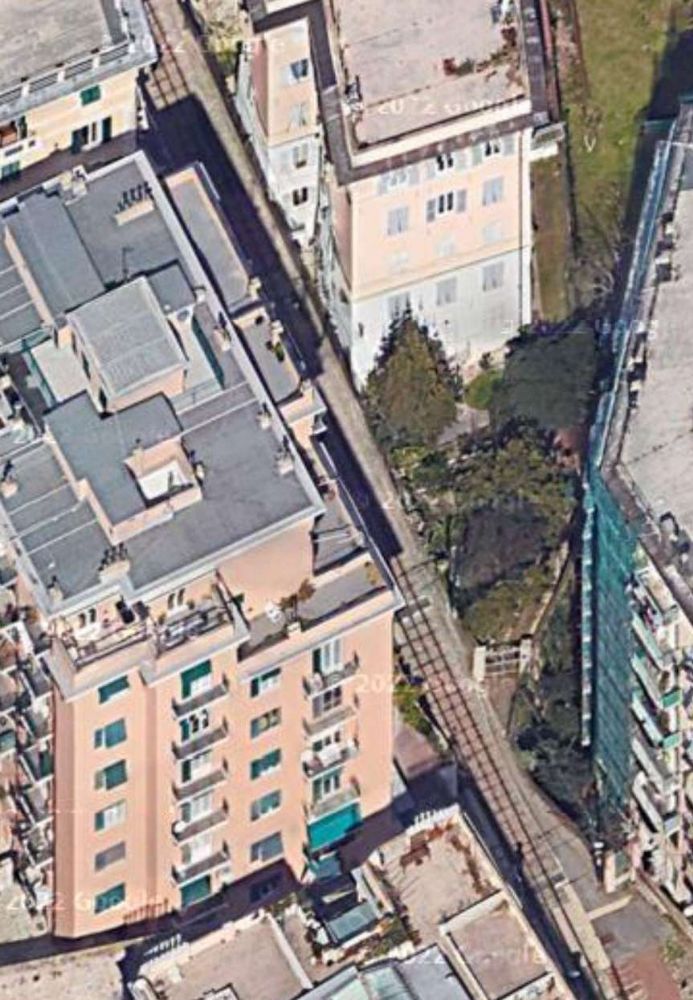

Built to 1.2 metre-gauge, the rack railway is 1,130 metres (3,710 ft) in length, and rises 194 metres (636 ft) with a maximum gradient of 21.4%. It uses the Riggenbach rack system and is electrified at 550 V DC. The single central passing loop uses fixed points, and the two cars have double-flanged wheels on one side and unflanged wheels on the other side, thus ensuring that each car keeps to its own side in the loop. [1][2]

The line serves 9 stops, including the two terminals, and, until the closure in early November 2024 for maintenance work, it operated an irregular timetable, with cars departing each terminus between every 30 and 40 minutes. [6]

A Journey Down the Line

We start at the head of the line at Granarolo. The first photograph shows Car No. 1 resting at Granarolo before its next journey South.

References

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principe%E2%80%93Granarolo_rack_railway, accessed on 10th November 2024.

- Funicolare Principe – Granarolo (1); in Funimag. Archived from the original on 2nd June 2019; via https://www.funimag.com/funimag07/GENOVA04.HTM, accessed on 19th November 2024

- Funicolare Principe – Granarolo (5); in Funimag. Archived from the original on 2nd June 2019; via https://www.funimag.com/funimag07/GENOVA08.HTM, accessed on 10th November 2024.

- Marco Carroza; (June 2019). Car No.2 returns to Genova; in Today’s Railways. No. 282; Platform 5 Publishing Ltd., June 2019, p17.

- https://www.amt.genova.it/amt/cremagliera-principe-granarolo-18, (English translation of the AMT website), accessed on 11th November 2024.

- Partenze dal capolinea della linea FGR, [Departures from the terminus of the FGR line] (in Italian). AMT Genova. Archived from the original on 2nd June 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20190602201756/https://www.amt.genova.it/amt/trasporto-multimodale/partenze/?linea=FGR&datagiorno=03%2F06%2F2019&orari=Orari, accessed on 11th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/j1WLKA1gcFyZr3te, accessed on 11th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/YnJLcUzeZ9GzyNkc, accessed on 11th November 2024.

- http://www.metrogenova.com/granarolo.asp, accessed on 13th November 2024.

- https://www.infogenova.info/da-non-perdere/57-ferrovia-principe-granarolo, accessed on 13th November 2024

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferrovia_Principe-Granarolo#/media/File%3ATra_le_case_(San_Francisco_a_Zena)_P2060637.jpg, accessed on 13th November 2024.

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferrovia_Principe-Granarolo, accessed on 13th November 2024.