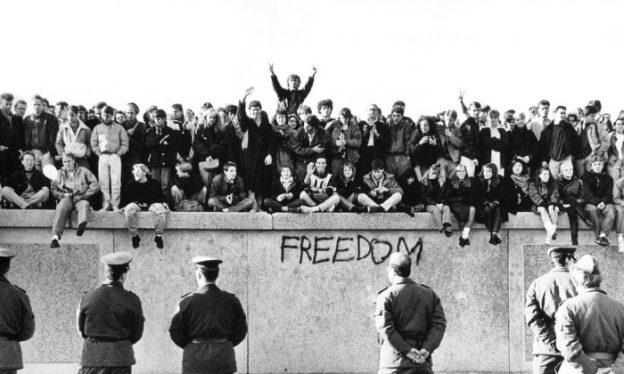

Have you ever experienced what it is like to be an outsider? The first time I went to Uganda in 1994, I had people’s warnings ringing in my ears. “Be careful travelling on the buses.” … “Everyone’ll be out to get what they can from you.” “Don’t walk around on your own at night.” I also had had my own fears about going to a different culture. And, yes, I did feel like an outsider. I was white, everyone else was black. I was treated like an oddity because I was different. A reversal of what many black and Asian people felt in coming here.

You may have experienced something like this – perhaps joining a new club, going to a new job, or a new town/city, going to the hospital for the first time. Unease in unfamiliar surroundings is something many of us experience. Often it isn’t helped by the way that those in the know, those who already belong, behave.

What would it have felt like as a Gentile coming into the temple in Jerusalem for the first time? An unfamiliar place with strange customs. It can’t be too hard to imagine some of the confusion and uncertainty that any Gentile must have felt.

The temple had its barriers even at the best of times – there was the Holy of Holies at the centre – where only God and the occasional male priest could go, next, separated by a richly embroidered curtain was the Holy Place where offerings to God were left by the priests (all of whom were male), next was the court where the altar sat – Jewish men were welcome here – then there was an outer court where Jewish women were allowed, and out beyond this – in the outermost court of the temple Gentiles were permitted. The temple system reinforced these divides, both gender and nationality. A place that was intended to proclaim God’s welcome had become a place where barriers obstructed access to God.

No doubt the Temple was a place of familiarity and comfort for those who attended regularly, particularly Jewish men. Everything had a structure and a place – it was somewhere safe and secure. But those very structures created barriers for others and a hierarchy of access to God. Rather than seeing the different outer courts as places of welcome for the outsider, Jews began to see those courts of lesser significance – and the Gentile Court, rather than being a place for worship, had become a place of business. The place where Gentiles could worship had become a market place.

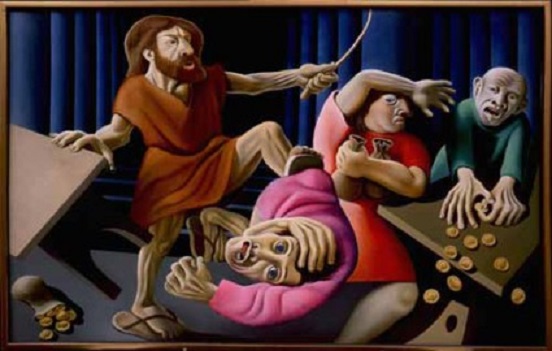

In our reading, Jesus erupts into this outer court, turning over tables and setting animals and birds free. And his comment in Mark’s version of the story reinforces his concern for the outsider; “It is written,” he says “God’s house will be called a house of prayer for all nations.” The temple, says Jesus, is not to be a barrier to worship but a place of worship. The way the temple is run, the way things are done, needs to draw in the outsider.

Later, Matthew’s Gospel tells us that, at the moment of Jesus death, the curtain in the Temple was torn in two from top to bottom – opening the path for everyone directly into God’s presence. No longer could anyone justify barriers which restricted access to God.

The Jews had allowed their place of worship to become a place that created barriers between God and those who came seeking him.

These short verses In John’s Gospel seem like a window into what it was like in the temple in Jesus’ day. But they are not a window, they are a mirror allowing us to see what we are like, they are a direct challenge to us:

How open are we to welcoming the outsider? Are we as welcoming as we think? What barriers do we place between God and those who seek him? Are we no better than the temple authorities?

How hard is it for new people to get their heads around our liturgy? How keen are we to have people in our services who don’t know what to do? What do we do to help those who are new? In a lot of our churches you can tell who is new … the regulars pick the seats at the back of church. I’m not sure why we see those as the best, but we hardly ever sit on the front row, do we. Often a guest will come into church and see the front seats clear and chose to sit there – anywhere else they’d be the best seats! It is only once the service starts that they realise their mistake – which bit of paper am I supposed to look at now, which book, do I stand or sit at this point in the service? Our guests end up feeling embarrassed. …. Is it any surprise that they choose not to return?

What happens after our services? Who talks to whom? Who seeks to include the outsider? One of our previous suffragan bishops, told a story about his wife Early in his ministry in the Diocese of Manchester he attended one church to preach and his wife went with him. At the end of the service she went to get her coffee and was very politely served and then she stood to one side, quietly drinking her coffee, and no one spoke to her.

When the Bishop introduced her to a few people, one woman said, “If only I’d known you were the Bishop’s wife, I’d have come over to talk to you.”

I wonder whether she had any real idea what she had just said about her own, and her church’s, attitude to the outsider.

How do we respond when children are noisy? How do we cope if someone sits in our regular seat? Do you have baptisms in your main church service? If so, what do you feel about Baptism families? Are we quicker to comment that they are bound not to return – rather than to welcome them, understanding just how alien the service must feel to them? How welcome do we make people feel? Are we really as helpful and welcoming as we=d like to think we are? We need to try to imagine what a newcomer sees and feels as they enter our buildings.

These short verses in our reading challenge each of us to take a step back to look at we do in God’s church, God’s temple. To try to look at what we do through the eyes of the outsider.

Jesus gave priority to the Gentile, to the outsider. He explodes in anger over the ugly barriers that religious people had created almost without thinking.

If nothing else, these short verses in our reading demonstrate that Jesus longs that we and all his followers will give priority, not to our own hopes and desires, but to those of our community and the wider world. Priority to drawing them into relationship with God.