How can we respond to the events which took place on Friday 28th February 2025 at the White House? How can we respond to the aggressive behaviour of Trump and Vance? It seems impossible to think of something we could do that will make any difference. Geopolitical events are so far beyond our control. It is so easy to feel depressed and powerless.

Perhaps we could donate to a charity working for the relief of suffering in Ukraine. Perhaps we could look for opportunities to support Ukrainians now living in our own areas. Perhaps there is something more we could do in our own relationships in response to what happened in the Oval Office.

First, let’s think about what happened in the White House on Friday 28th February 2025. …..

An intriguing analysis has been circulating online regarding the psychological aspects of Zelenskyy’s meeting with Trump and Vance. It seems that we witnessed a masterclass in gaslighting, manipulation, and coercion on the part of Trump and his entourage. This analysis was shared on Facebook by Yuliia Vyshnevska a Ukrainian lawyer living in Oxford (UK). [1]

These are the key points made by Yuliia:

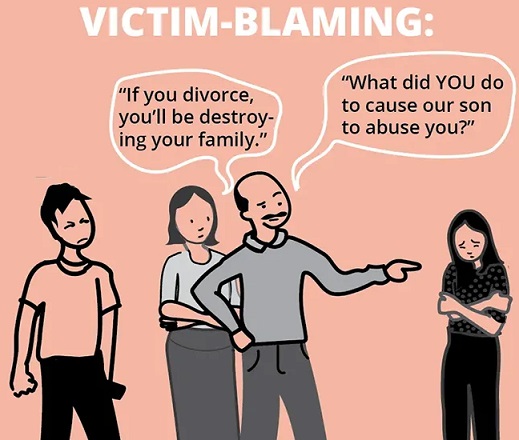

Blaming the victim for their own situation – Trump explicitly tells Zelensky: “You have allowed yourself to be in a very bad position.” This is classic abuser rhetoric—blaming the victim for their suffering. The implication is that Ukraine itself is responsible for being occupied by Russia and for the deaths of its people.

Pressure and coercion into ‘gratitude’ – Vance demands that Zelensky say “thank you.” This is an extremely toxic tactic—forcing the victim to express gratitude for the help they desperately need, only to later accuse them of ingratitude if they attempt to assert their rights.

Manipulating the concept of ‘peace’ – Trump claims that Zelensky is “not ready for peace.” However, what he actually means is Ukraine’s capitulation. This is a classic manipulation technique—substituting the idea of a just peace with the notion of surrender.

Refusing to acknowledge the reality of war – Trump repeatedly insists that Zelensky has “no cards to play” and that “without us, you have nothing.” This is yet another abusive tactic—undermining the victim’s efforts by asserting that they are powerless without the mercy of their ‘saviour.’

Devaluing the victims of war – “If you get a ceasefire, you must accept it so that bullets stop flying and your people stop dying,” Trump says. Yet, he ignores the fact that a ceasefire without guarantees is merely an opportunity for Russia to regroup and strike again.

Dominance tactics – Trump constantly interrupts Zelensky, cutting him off: “No, no, you’ve already said enough,” and “You’re not in a position to dictate to us.” This is deliberate psychological pressure designed to establish a hierarchy in which Zelensky is the subordinate.

Forcing capitulation under the guise of ‘diplomacy’ – Vance asserts that “the path to peace lies through diplomacy.” This is a classic strategy where the aggressor is given the opportunity to continue their aggression unchallenged.

Projection and distortion of reality – Trump declares: “You are playing with the lives of millions of people.” Yet, in reality, it is he who is doing exactly that—shifting responsibility onto Zelensky.

Creating the illusion that Ukraine ‘owes’ the US – Yes, the US is assisting Ukraine, but presenting this aid as “you must obey, or you will receive nothing” is not a partnership—it is financial and military coercion.

Undermining Ukraine’s resistance – Trump states that “if it weren’t for our weapons, this war would have ended in two weeks.” This is an attempt to erase Ukraine’s achievements and portray its efforts as entirely dependent on US support.

Yuliia’s Conclusion …. Trump and his team employed the full spectrum of abusive tactics: gaslighting, victim-blaming, coercion into gratitude, and manipulation of the concepts of peace and diplomacy. This was not a negotiation—it was an attempt to force Zelensky into accepting terms beneficial to the US but potentially fatal for Ukraine.

Our Response?

While we cannot influence relationships in international politics, however, we can choose our own actions and behaviours. Bullying and abusive behaviour can be part of many relationships. This has been brought into high relief by the events in the Oval Office, but we might recognise some of these behaviours either in ourselves or in others that we know. If so, we should seek help to change/overcome those behaviours.

There are already people working in our local communities supporting those suffering abuse or who support those who are regaining their dignity after experiencing shaming or abuse. Others are working to help abusers address their own behaviour. All these are worthy of our support. Some are shown below.

Support for charities working in Ukraine, and for Ukrainians in our local community is a priority. In itself, it is a firm and particular response to what we saw happening in the Oval Office. Some of these charities appear toward the end of this article.

Charities Seeking to End Abuse – Working with Abusers (to change behaviour) and with Those Who Have Been Abused

These charities include:

NAPAC: The National Association for People Abused in Childhood supports adults who have experienced childhood abuse;

Refuge: Supporting those who have experienced abuse;

Karma Nirvana: A specialist charity for victims and survivors of honour-based abuse;

Survivors UK: runs the National Male Survivors Online Helpline – a webchat and SMS service for men, boys and non-binary people who have experienced sexual abuse at any time in their lives;

NSPCC: has been protecting children for over 140 years;

Children 1st: offers a range of services for children, young people and their families who have been affected by physical, sexual or emotional abuse in Scotland. There is a network of local support groups across the country;

The Lucy Faithful Foundation: offers a number of programmes to help people move towards real change and understand their own, or their friend or family member’s, illegal behaviour.

And local charities, such as LEAP which works with Children and Families in the Tameside area of Greater Manchester.

Charities Proving Support to Ukraine and Ukrainians

Among others, these charities and other organisations include:

British Ukrainian Aid: A grassroots charity that believes in the power of civil society and volunteers united by a single goal: to see Ukrainians overcome the hardships of the war and live in dignity and prosperity in independent Ukraine;

United Help Ukraine: Provides humanitarian aid, including clothing, medical supplies, and rehabilitation for wounded soldiers;

UNICEF: Funds non-governmental and volunteer organizations that help civilians, including children, young people, and vulnerable people;

CARE International: Provides emergency food and water to Ukrainian refugees;

Sunflower of Peace: A non-profit organization that supports the people of Ukraine affected by the Russian military invasion;

Barnardo’s: Provides a free helpline to support Ukrainian families arriving in the UK;

British Red Cross: Provides practical and psychosocial support to people displaced from Ukraine who have arrived in the UK;

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees): Works in Ukraine and neighbouring refugee-hosting countries, providing access to clean water, health care services, cash transfers and other critical support;

UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF): CERF enables humanitarian responders to deliver life-saving assistance whenever and wherever crises strike.

World Food Programme: The world’s largest humanitarian agency – provide life-saving support to the most vulnerable families;

IOM – International Organization for Migration: Aims to Aid Two Million People in Ukraine in 2025 as War and Displacement Continue ;

UN Women: Works with Women and Girls in Ukraine;

The International Rescue Committee: seeks to respond where needed most;

Humanity & Inclusion Ukraine Emergency Appeal — an emergency fund to support disabled and vulnerable people in Ukraine;

Ukraine Charity humanitarian appeal — raising funds to procure medicine and medical equipment. Ukraine Charity is a UK registered charity;

PLAST — Donate to the Ukrainian scouts association to help provide humanitarian, medical and rehabilitation support to scouts and their families during Russia’s invasion;

for PEACE — The forPEACE Ukraine Relief Project works with Ukrainians to deliver targeted medical and humanitarian aid, connecting international financial support with Ukrainian networks, medical professionals, and trusted community organisers on the ground;

Voices of Children Charitable Foundation — since 2015, has provided free psychological assistance to children and their families affected by the war. From the full-scale invasion, the foundation has supported more than 64,000 children and adults. All donations go to individual and group, and online psychological sessions, activities (camps, art therapy, excursions), rehabilitation, and humanitarian aid for children and parents.

Leleka — focusing on the urgent supply of critical medical supplies and protective gear to Ukraine’s defenders and civilians

Razom for Ukraine and Nova Ukraine — US-based emergency appeals;

Rescue Now — this Ukrainian charity evacuates people from war zones and supports the elderly in eastern Ukraine. The Rescue Now team is supporting people in the Kherson region affected by mass flooding following Russia’s destruction of the Kakhovka dam.

References/Notes

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/18YrnqBkNM, accessed on 2nd March 2025.