The featured image shows FS940-002 141T (2-8-2T) in preservation in Piazza al Serchio, © MPW57, Public Domain. [20] The electrification of the two lengths of the Cuneo-Ventimiglia line(see the notes below), left the portion of the line between the two Italian border stations of San-Dalmazzo and Piena needing dedicated steam locomotives. The role was undertaken by a series of nine FS940 141T locos built in 1922 and 1923 of which FS940-002 was one. These locos were able to haul a load of 160 tons at 50 km/h on a 25 mm/m gradient.

I am writing this article having just returned to Menton where we were staying in November 2025. We travelled to and from Tende which is the terminus of Zest Bus Ligne 25. There was little action to observe at the railway station.

The line from Nice to Tende via Breil-sur-Roya was closed until the beginning of 2026. The alternative route from Ventimiglia was still active but we did not see a train during the two hours we spent at Tende.

This is the ninth article in a series relating to the railway between Cuneo, Nice and Ventimiglia. In earlier articles about the line from Cuneo to the sea we covered the length of the line from Cuneo to Breil-sur-Roya and then to Ventimiglia, before looking at the line between Breil-sur-Roya and Nice. As we looked at the two routes we also looked at the history of the line over the period before it’s opening in 1928. These articles can be found here, [3] here [4] here, [5] here, [6] here, [7] here, [8] here, [9] and here. [10]

This article covers the period from 1928 to 1939. The primary source for this article is the second volume of Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun & Gerard de Santos’ series ‘Les Trains du Col de Tende‘ which is written in French. …

A. Steam Operation Alone (1928-1930)

The First Months of Operation

The commercial service on the line began on 31st October 1928.

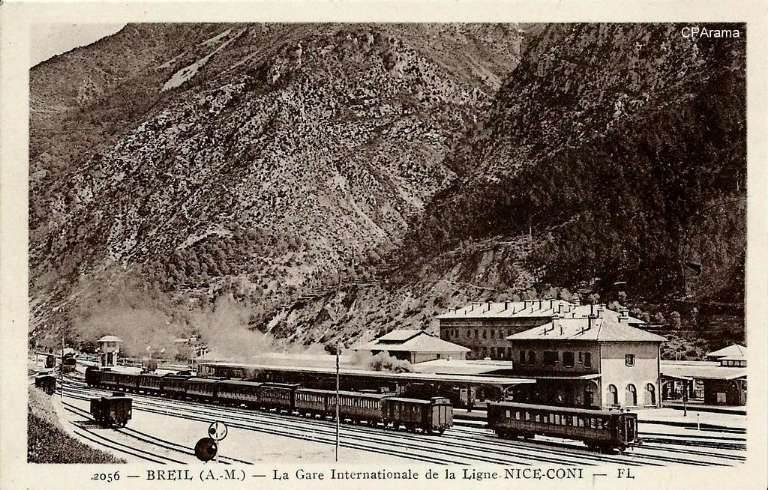

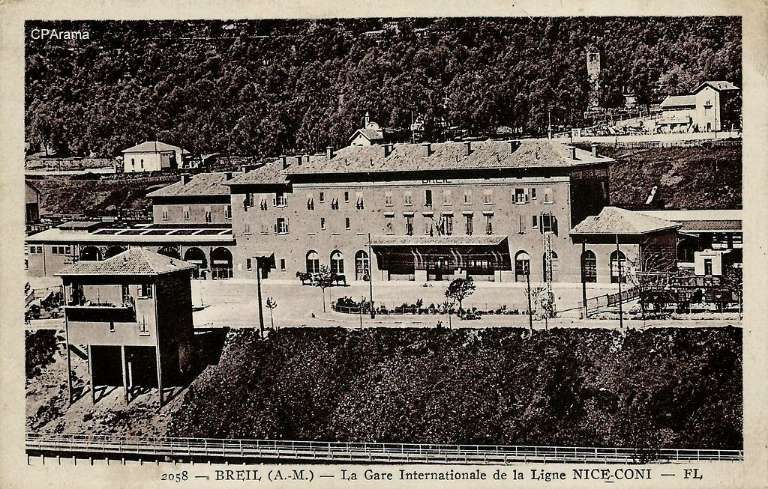

The line between Nice and Breil-sur-Roya was served by the PLM with five passenger services in each direction daily. From Nice to Breil, three were stopping/local trains which Barnardo etc al refer to as ‘omnibus’ services. These took about 1 hr 30 mins to cover the 44km journey. Two were ‘express’ services which stopped only at Nice-Saint-Roch, L’Escarène and Sospel. They covered the distance in about 1 hr 14 mins run in 1 hr 13 or 14 mins. All five trains included direct carriages to destinations beyond Breil.

In the opposite direction, a similar schedule was followed, with three ‘omnibus’ services and two express services.

On the Italian Cuneo-Ventimiglia route, the service was almost the same with five journeys from Cuneo to San Dalmazzo, six between San Dalmazzo and Breil, and then five again between Breil and Ventimiglia. Journey times varied from 3 hrs 15 mins for ‘direct’ services to 3 hrs 50 mins for both ‘omnibus’ and ‘express’ services which included a stop of 10 to 12 mins for customs control and refueling at San Dalmazzo, 17 to 20 minutes at Breil, and 2 to 4 minutes at Piena. [1: p7]

In the opposite direction, the best times were between 3 hrs 45 mins for ‘direct’ trains and 4 hrs 15 mins for ‘omnibus’ services. The longer journey times were because of a longer gradient and a stop of at least 20 minutes in Breil to wait for connections from Nice. From morning to evening, six trains ran in this direction. ‘Direct’ trains ran with only four commercial stops (at Cuneo, San Dalmazzo, Breil, and Piena), but they made at least one stop at Tende, or at Vievola to allow the single line ahead to clear. Refueling also took place at Limone station, even though no commercial stop was shown on the timetable. Isolated between Breil and the northern border, Fontan-Saorge station was served in each direction by four ‘omnibus’ and ‘express’ services, and by the morning northbound ‘direct’ service. [1: p7]

Italian services had an additional class of train to services provided by the French. These were known as ‘accelerato’ services. “The term ‘accelerato’ (accelerated) appeared in Italian railway terminology in 1889 to refer to a train that briefly stopped at every stop, running slightly faster than ordinary ‘omnibus’ services. This term gave way in 1967 to the term ‘local’ trains, which are now known as ‘regional’ trains.” [1: p14]

Banaudo et al tell us that, “In the years following the opening, services were slightly modified to accommodate new needs, particularly in the tourism sector.” [1: p9]

Changes were made to international services on 15th May 1930, and the following summer, the ‘direct’ southbound evening service made a commercial stop at Tende station from 1st July to 30th September, but this trial was not repeated.

Banaudo et all tell us that, “On the French side, the Nice-Breil service was increased to six daily services, plus a seventh service running on Sundays and summer holidays. Fontan-Saorge station continued to be served by Italian trains, supplemented seasonally by one or two Breil-San-Dalmazzo-di-Tenda shuttles.” [1: p14]

From 1928, a daily goods train was “operated by the PLM on the French branch of the line. It left Nice-Saint-Roch station at 9:46am and arrived in Breil at 1:45pm, after serving all stations open to ‘low-speed’ traffic: La Trinité-Victor, Drap-Cantaron, Peille, L’Escarène, and Sospel. Depending on the weight of the train, a second engine was used to bank the train at the rear on the way to Sospel [from Breil-sur-Roya], from where it descended steeply to Nice. The lead locomotive and its driving crew handled shunting operations in Breil. … Another engine and its crew, taking over in Breil, took the return train, departing at 4:48pm, arriving in Nice-Saint-Roch at 9:31pm.” [1: p26-27]

The FS operated a daily goods train from “Cuneo to Ventimiglia. Depending on needs, additional trains were put on to San Dalmazzo or Breil.” [1: p27]

Most of the trade on the two lines “included agricultural products: corn, straw, wheat, vegetables, and wine imported from Italy; [with] timber and bagged potash fertilizers (sylvinite) exported. Manufactured goods and construction materials also arrived in the towns along the line.” [1: p27] The route was also used to convey empty wagons to Liguria to relieve the congested Giovi and Cadibona routes. Livestock from Central Europe, such as pigs from Czechoslovakia, was brought via Cuneo.

In the autumn of 1928, the transhumance of the Roya herds made relatively little use of the railway. (Transhumance is the seasonal movement of livestock between fixed pastures, typically moving from lower valleys in winter to higher mountain pastures in summer). Apparently, this was because of the impracticability of the ‘ low-speed’ train timetable for local farmers. In the spring of 1929, the timetable was adapted to significantly reduce shunting time in the stations. However, the shepherds of Tende and Briga found the complex administrative formalities for crossing the border by train too difficult. They “preferred to reach Breil on foot with their flocks, only loading them onto the train for the final leg to the traditional wintering grounds of the Paillon Valley and the Nice region.” [1: p28]

The new railway was unable to take much advantage of local mineral resources, which were mainly exhausted by 1927, the year before the line opened. [1: p28]

A cable car was installed to transport ore “from Lake Mesce to San Dalmazzo, where Europe’s first electrolytic processing plant was established to produce zinc. In the year of closure, 40,000 tons of zinc concentrates and 5,000 tons of lead were produced, and the metal … was shipped by rail to Italian industries. However, the sudden collapse in metal prices made operations unprofitable and led to the closure of the mine and plant.” [1: p28] A few short years after opening to traffic, tonnages of freight transported by the two lines suffered from the global economic crisis that preceded the beginning of the Fascist government’s protectionist policies. Banaudo et al comment that “the tonnages transported were far from reaching the level hoped for by the promoters of the line. In 1931, they represent 300 gross ton-kilometres compared to 3500 on the Fréjus line and 6000 on the Saint-Gothard line.” [1: p28]

B. Two-Phases of Electrification (1931-1935)

Electric Traction in Italy

Despite the steam locomotives used on the line being designed for mountainous terrain, the use of steam power posed significant problems. Passing through so many tunnels meant that the locomotive drivers and firemen experienced exhaustion, if not more. Smoke and steam together made conditions dirty for both workers and passengers. Train speeds were inevitably low due to the limited power of the engines and the steep gradients.

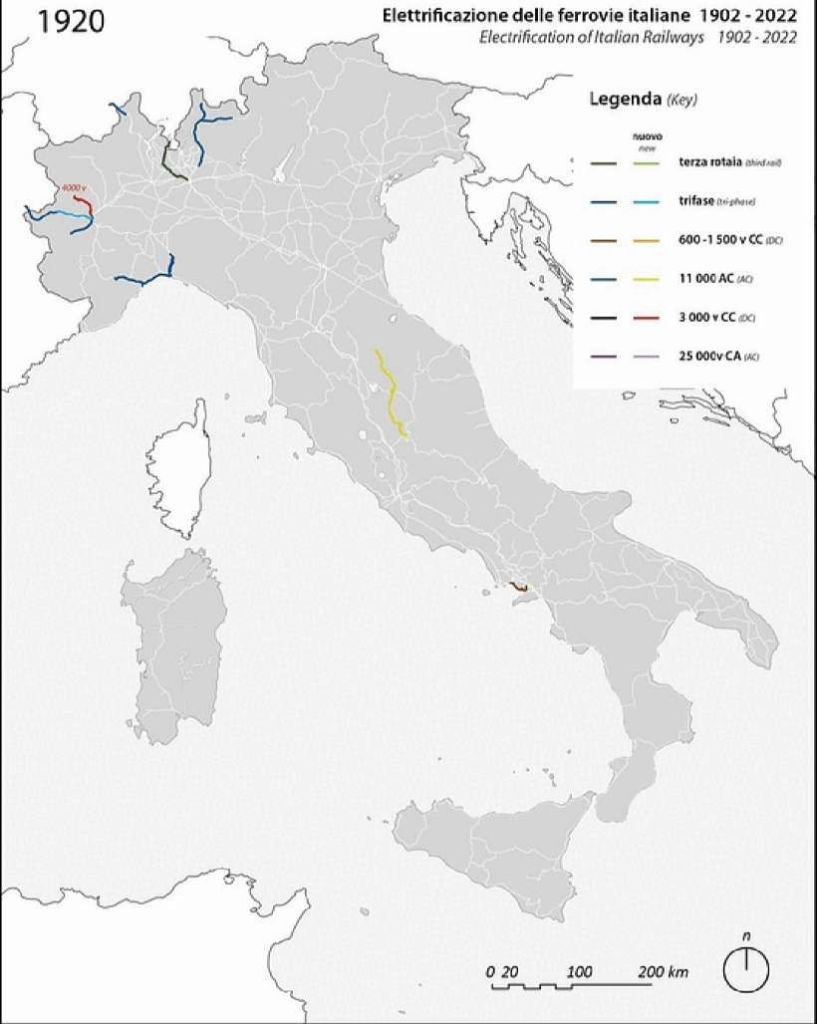

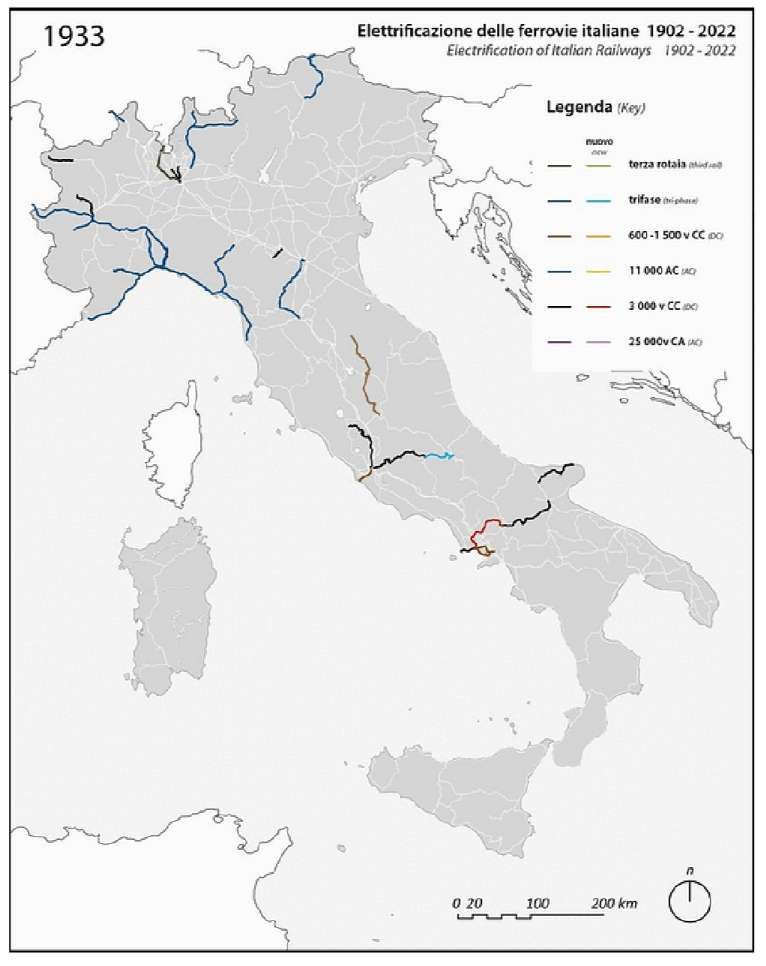

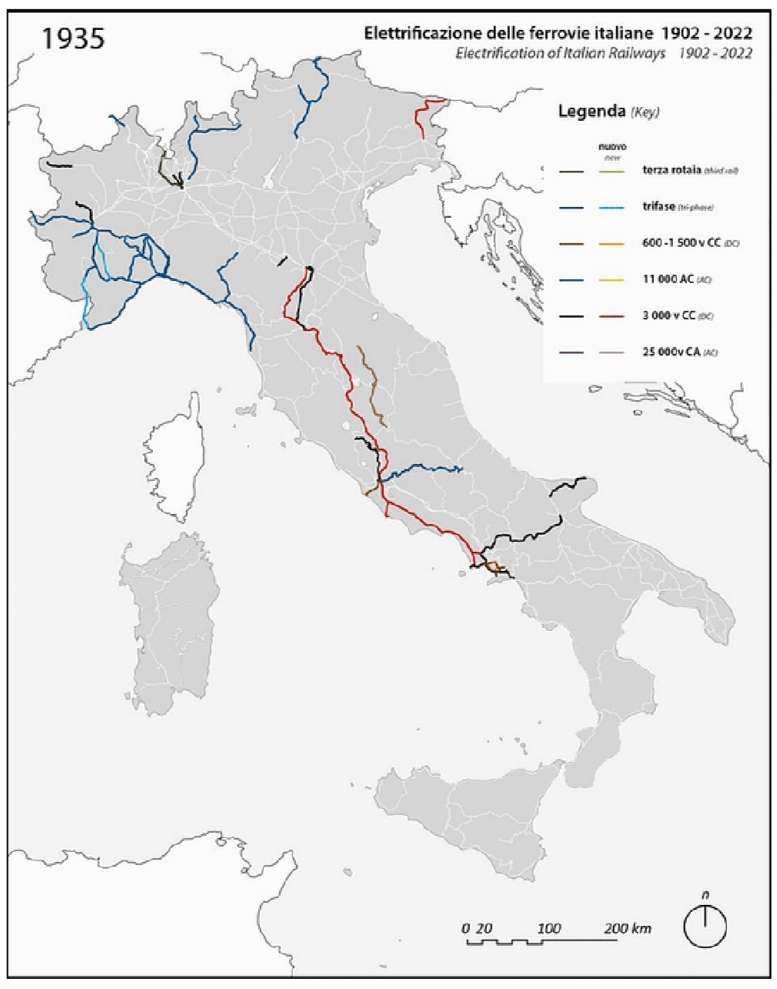

Banaudo et al say that “In 1930, the two direct trains covered the 100 km from Cuneo to Ventimiglia in 3 hours 10 minutes with three intermediate stops, an average of 31.6 km/h. In the opposite direction, where the climb is almost continuous for 62 km, it takes them 3 hours 35 to 40 minutes to reach Cuneo, an average of between 27 and 28 km/h. Added to this are very high operating costs, due to the absence of a coal basin in continental Italy, which meant that all the coal used as fuel for the FS locomotives had to be imported. … For all these reasons, Italy began to electrify many of its highly-trafficked mountain lines even before the First World War. Following the successful experiments carried out … in the Lombardy valley of Valtellina from 1901, the system chosen as the standard for future Italian electrification was three-phase current of 3400 volts and a frequency of 16 and two-thirds hertz, distributed by a two-wire overhead line. … Electrification was applied in stages from 1911 to 1914 to the Genova – Torino and Milan lines crossing the Ligurian mountains via the Giovi Pass. Next, from 1912 to 1915 on the international Torino – Modane line via the Frejus tunnel. In the post-war years, the number of electrified lines increased until Italy had the largest electrified network in the world in 1926, with 504 locomotives in service and the longest continuous line with electric traction, 450 km from Modane to Livorno.” [1: p34]

From 1920 – 1933 – Three-phase AC reached maturity, and experiments with 3 000v DC began. “3000v DC was first rolled out in 1927 between Benevento and Foggia (part of the Naples-Bari line), and in a few local railways in the following years: Naples’s Cumana, Milan’s FNM, and the newly opened Aosta – Pré Saint-Didier and Rome-Viterbo. After this successful experiment, 3Kv DC was adopted as the blueprint for the big roll-out that happened in the following period.” [11]

The new line across the Col de Tende was ideal for electrification given expected high traffic demand and the proximity of significant hydroelectric resources of the Roya basin. “As early as 27th April 1927, even before the line was put into operation, the Italian Ministry of Public Works expressed its desire to electrify the line to its French counterpart. The French authorities were not opposed, provided that Italy covered all the costs incurred by the operation on French territory.” [1: p34]

“The FS Board of Directors decided to electrify the sections located on Italian territory, namely Cuneo-San Dalmazzo-di-Tenda and Piena-Ventimiglia, as a first step. … Construction began in 1929 with major civil engineering work to adapt … structures … for electrification, the layout of certain curves was straightened, and the original rails, already around forty years old, were replaced north of Limone. The station installations were modified. Those whose track plan included double turnouts (points providing three directions) had these devices replaced by a pair of single turnouts to avoid the inextricable tangle of the contact line wires, which required special insulation measures when crossing the track equipment. At Limone, the track was reworked and the small locomotive shed demolished to make way for a substation. In San-Dalmazzo-di-Tenda, the construction of the substation required major earthworks between the Rioro spiral tunnel and the viaduct, including 3,400 m³ of excavation.” [1: p34]

“The excavated material was “reused to widen the station plateau and expand the goods yard. At Piena, an additional retaining wall was built and a traverser installed to facilitate engine change manoeuvres. This allowed the electric locomotive arriving from Ventimiglia to be released from its train making way for a steam engine, for which, the FS obtained authorization from the French government to extend the overhead line by a few dozen metres beyond the Riou viaduct.” [1: p40]

“The power stations of San-Dalmazzo, Piena and Bevera of the Compagnia Imprese Elettriche Liguri (CIELI) were equipped with new alternators producing three-phase current at the specific frequency of 16 & two thirds hertz (i.e. one third of 50 hertz) adopted at that time by several European railway networks. High-voltage lines of 60,000 volts, connected to the Busca Ceva and San-Dalmazzo-di-Tenda Lavagnola lines, carried the current to five substations built by the FS at Robilante, Limone, San-Dalmazzo, Piena and Ventimiglia. These each had four transformers … except for the San-Dalmazzo substation which was equipped with six transformers. … The voltage was lowered to 4000 volts to be distributed to the railway overhead lines. The substations themselves were connected by a triangular ‘feeder’ at the Arma-di-Taggia substation, on the Ligurian Riviera, to allow mutual reinforcements of power supply between the electrified lines of Liguria and Piedmont.” [1: p40]

Overhead lines were installed at night, avoiding disruption to traffic on the line. Metal poles were provided generally with brackets used In tunnels and suspended 5.5 metres above the track except in stations where a 6 metre clearance was provided.

The current was drawn by the locomotives at an average voltage of 3400 to 3600 volts. To limit voltage drops on the long gradients of the southern section where the power supply was heavily used, the contact wires were doubled, two pairs of wires were used. In the helical loops, additional conductor wires were stretched over pylons between the lower and upper levels of the loop, without following the track layout.

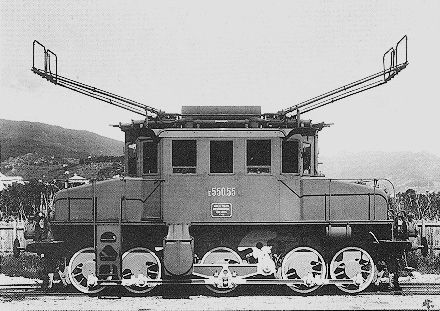

In 1931, the FS powered up a total of 184 km of line. “Operation of the northern branch was entrusted to four E 554 group locomotives based at the Cuneo depot, while to the south, Ventimiglia had two E 550 locomotives, sometimes supplemented by E 551s, for service to Piena.” [1: p41]

The line operated with steam over the central section until the French were in a position to open an electrified line in the Roya Valley on French territory.

Italian Electric Locomotives and Autorails

Banaudo et al’s book includes copious photographs and plans associated with this first phase of the electrification and provides details of the 3-phase electric locomotives employed on the line. Common to all of these locomotives were side panels in the bodywork “housing a liquid rheostat, an oil-filled reversing switch, various auxiliaries, and, on some units, a vertical oil-fired boiler for heating steam trains. Cooling the rheostat and powering the boiler create the astonishing spectacle of an electric locomotive emitting plumes of steam and refueling at stations!” [1: p46]

Banaudo et al continue: “On freight locomotives, connecting the [two] motors in series or parallel allowed for speeds of 25 or 50 km/h. On passenger locomotives, parallel coupling and pole switching achieved speeds of 37.5, 50, 75, or 100 km/h. Each motor was connected to both ends of a Von Kando triangular connecting rod or a Bianchi articulated link system, which transmits power to one of the axles. These are rigidly mounted on the chassis and connected to each other by coupling rods, similar to a steam locomotive. On passenger locomotives, the coupled axle set is flanked by two pony trucks or carrying bogies.” [1: p46]

From 1931 onward, the line over the Col de Tende was primarily operated by five-axle locomotives. “The FS has three series built from 1908 to 1931. The E 554.001 to 183 based in Cuneo initially served the Cuneo San-Dalmazzo-di-Tenda section, while the E 550.001 to 186 and E 551.001 to 183 based in Ventimiglia operated the shuttle to Piena. From 1935, with the electrification in French territory, the E 554s ran the entire line. They developed a power of 2,000 kW and handled trains of approximately 500 [tons] with single traction and 900 [tons] with reinforcement, at a fixed speed of 50 km/h.” [1: p46]

“Later, around 1942, type 1D1 passenger train engines, series E 432.001 to 040, handled the direct Torino – Ventimiglia trains. Depending on the tonnage, an E 550, 551, or 554 were used as bankers on the north section between Cuneo and Limone.” [1: p46]

Banaudo et al have a series of drawings of these locomotives. These include line drawings and the different liveries that the locomotives carried during their working lives. [1: p47-50]

The electrification of the two lengths of the Cuneo-Ventimiglia line, left the portion of the line between the two Italian border stations of San-Dalmazzo and Piena needing dedicated steam locomotives. The role was undertaken by a series of nine FS940 141T locos built in 1922 and 1923. These locos were able to haul a load of 160 tons at 50 km/h on a 25 mm/m gradient.

Banaudo et al comment that the operation of the line markedly improved with partial electrical operation. A constant speed of 50 km/h could be maintained even on steep gradients. “The time savings compared to steam traction were impressive: in the north-south direction, direct trains connected Cuneo to Ventimiglia in 2 hours 35 to 40 minutes, and in the uphill, more rugged, direction, in 3 hours 00 to 05 minutes.” [1: p53] This represented at least a 30 minute improvement in journey times! As a result, the timetable was overhauled with effect from 15th May 1931.

Banaudo et al tell us that, with two pairs of goods trains daily on each line, the number of trains each day at Breil-sur-Roya was thirty-six, plus a few excursion trains.

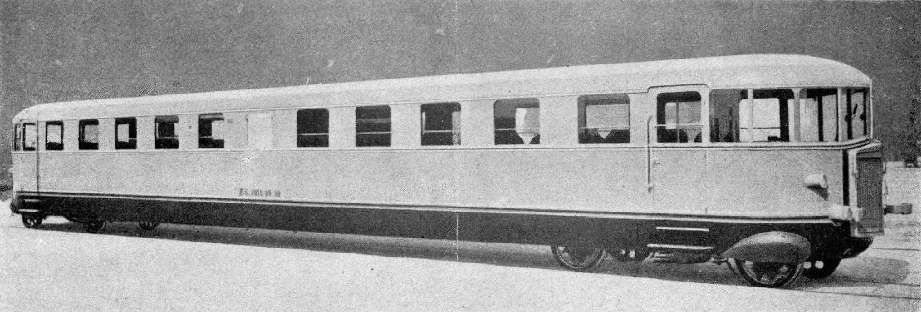

During the winter of 1934/35 a railcar service was trialed between Ventimiglia and Oulx. Fiat designed these vehicles used. The Fiat automotrici were modern, efficient and beautifully designed. “‘The Littorina’ can be regarded as a co-production of Mussolini and Fiat president Agnelli. The new train type helped achieve Mussolini’s political goals, proudly carrying the symbol of his fascist party on its front.” [16]

Agnelli “acquired pastureland between 1928 and 1931 in the municipalities of Cesana and Pragelato, between Val Cenisio and Val Chisone, not far from the Montgenèvre Pass. There he built hotels, ski lifts, and a resort named Sestriere, which was granted the title of commune by decree of 18th October 1934. For the launch of the first season of “his” resort, Agnelli decided to make a big splash: a fast rail link named ‘Riviera Sestriere’ was opened from 21st December 1934, to 30th March 1935, to transport Ligurian customers to the ski slopes in just a few hours.” [1: p59]

More can be found out about the Fiat Littorina autorail/railcars here. [19]

“The ALb 80.04 railcar, specially refurbished with comfortable seats, sound system, bar and ski storage, ran three times a week. Monday, Wednesday and Friday in [a northerly] direction: Ventimiglia 14:55, Cuneo 16:53 54, Torino-PN 17:53 / 57, Oulx-Claviere-Sestrieres 19:00. From there, a coach leaves at 19:10 for Sestriere, arriving at 19:55. The return journey took place Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday Sestriere 18:45 / 50, Torino-PN 20:10 / 17 according to the timetable Sestriere 18:00, Oulx-Claviere-Cuneo 21:14 / 16, Ventimiglia 23:15. From this station, connections were provided to and from the resorts of the Riviera dei Fiori.” [1: p60]

Banaudo et al continue: “Despite the interest it provoked, the ‘Riviera Sestriere’ was not renewed during the winter of 1935-36: this must be seen as an effect of the international crisis caused by the Ethiopian War, but also the development of the winter sports resort of Limone, served directly by train, which attracted a large proportion of Ligurian customers.” [1: p61]

Banaudo et al take time to look at the brief association between autorails and the Col de Tende line. [1: p64-67]

In September 1933, the arrival in Nice of the first two-axle railcars … gave hope of seeing this equipment appear on the Fontan-Saorge shuttles, but from November 1933 the PLM assigned these four vehicles to the Nice-Menton service. The local press then speculated on the possible use of a 36-seater Micheline Type 15 Express, which ran for two days between Nice and Breil in November 1933. However, this was a demonstration of a pre-production prototype that would never provide regular service on the Côte d’Azur or surrounding areas.

A year later, Italy introduced the Littorina service mentioned above which we have already seen was not to be used in the following winter season. It appears that some charters made use of similar Breda autorails in the winter of 1937-38.

The year 1939 saw the short-lived creation of a Torino San Remo express train, which ran from 15th May to 31st August 1939. A Fiat railcar of the ALn 40 series 1001 to 1025, delivered in 1936-37, was assigned to this prestigious service. These vehicles offered 40 seats in comfortable armchairs, and a small kitchen allowed for the preparation of meals served at the seats. Two 145 hp Fiat six-cylinder diesel engines powered one axle of each bogie via mechanical transmission. This railcar beat the record of the ALb 80 from Riviera to Sestriere by a few minutes four years earlier, covering the distance in a time that has since remained unmatched, as shown in the table on the following page.

A final series of railcars appeared on the Col de Tende line “in 1939, when Fiat tested two ALn 772s 1001 to 1100. These new-generation railcars, which stood out from the classic ‘Littorine’ units previously used by the FS, offered 72 seats and were powered by two 150 hp Saurer six-cylinder diesel engines, with Ljungströms hydraulic transmission and the possibility of coupling into multiple units. This equipment was assigned to Turin in May 1940, but it was not until well after the war that it was seen in regular service between Cuneo and Limone.” [1: p65]

Electrification in France

The FS sustained pressure on France to electrify the length of the line between San-Dalmazzo-di-Tenda and Piena. It submitted a preliminary design to the PLM which was modified to meet French legal issues and PLM company policy. Banaudo et al tell us that to establish the conditions for the electrification of the French section, “two meetings were held between representatives of the two countries, on 20th February 1934, in Breil and on 21st February in Nice. On 18th July, the Franco-Italian agreement was signed. It passed through all the necessary legal hoops by the Autumn. … The entire electrification costs were to be borne by the FS … [with] commissioning of Italian locomotives running on the section of line in question … subject to authorization from the PLM.” [1: 74]

Construction began in mid-January 1935. The work was completed by 17th April 1935. The full cost was covered by the Italians. The new service began on 21st April 1935 although the formal opening did not take place until 28th April.

Full electrification allowed a further acceleration of service in the Roya Valley with the journey towards Cuneo taking a little over 2 hrs 30 mins and the return journey taking 2 hrs 50 mins.

Meanwhile four trains ran each way on the Nice to Breil line with a journey time of less than 1 hr 30 mins for the local service which called at all stations and around 1 hr 10 mins for the fast service which only stopped at Nice-Saint-Roch and L’Escarene.

Steam traction disappeared from the Italian line and traffic through Breil-sur-Roya on that line was almost exclusively handled by Class E554 locomotives. Banaudo et al tell us that the line was serviced by self-propelled vehicles which were stationed as follows:

- Cuneo: draisines (railcars) 614.29950 and 508.41462 and auto-echelle (ladder-car) 508.826.

- Limone: auto-echelle 508.839.

- San-Dalmazzo-di-Tenda: draisine 618.36178, and auto-echelle 509.519.

- Breil-sur-Roya: auto-echelle 508.858.

- Piena: motorised quadricycle Puch 1119.

At San-Dalmazzo-di-Tenda, electrification removed the need for banking engines and as a result such engines were not available to work the goods yard. Banaudo et al tell us that “A shunting locomotive No. 4120 (later numbered in the 207 series) was therefore assigned to the San-Dalmazzo station upon leaving the factory. It would later be replaced by No. 4146 (renumbered in the 206 series). The latter would be destroyed at Tende station during the war.” [1: p84]

C. A Time of Discord (1936-1939)

The Crisis of the Ethiopian War

In the period from 1928 to 1936 the Col de Tende line played an important international role. Mussolini’s expansionist, imperialist policies gradually but inexorably saw relations between Italy and France deteriorated. After Mussolini’s Ethiopian campaign between October 1935 to May 1936, the League of Nations imposed sanctions against Italy. Border crossings in the Roya Valley became difficult, the export of Italian and French products across the border was prohibited.

The autumn and spring movement of livestock (transhumance) were particularly affected by border problems.

Some traders found ways to circumvent the embargo to export Italian products to France, under the provisions of earlier laws. When Nice was annexed to France in 1860, the municipalities of Tenda and Briga, remained within the new Kingdom of Italy, secured free entry for their products into France to compensate for the loss of their traditional markets and the difficulties of communication with Piedmont in winter. Products from elsewhere in Italy were labelled as products from the Tenda and Briga area to circumvent the prohibition.

“Despite the political crisis, the international service schedule was maintained without significant changes. Only the Torino San Dalmazzo and return dining car disappeared from the composition of direct trains … starting with the summer timetable of 15th May 1936. That year was marked by the rise of the Limone winter sports resort, which began to attract a middle-class clientele from the towns of the Ligurian Riviera. From December 1936 to March 1937, two “snow trains” ran every weekend: a Torino-Limone on Saturday evening and a Ventimiglia-Limone on Sunday morning with a return working in the evening. For athletes wishing to extend their stay on the slopes, the San-Dalmazzo – Ventimiglia morning service departed from Limone on Monday mornings. These seasonal services would continue for the following two winters.” [1: p90-91]

“During 1933-34, the Lavina bridge, at the southern entrance to Breil station, suffered significant deformations due to the subsidence of the embankment undermined by a vein of gypsum. The structure had to be partially rebuilt: the two main tracks towards Nice and Ventimiglia were placed on a metal span coated in concrete, while the head shunt for the goods sidings remained in place on the original arch.” [1: p91]

During this time fortifications were enhanced by both the French and the Italians along the line. Banaudo et al focus on these works in a dedicated section within their book. Pages 92 to 99 cover the work on fortifications.

“As the months passed, the military headquarters of both countries accelerated the fortification of the border peaks and valleys. Alpine troop maneuvers increased on both sides, involving the stations of L’Escarène and Sospel in France, as well as those of Limone, Vievola, and San-Dalmazzo in Italy. In 1937, as [Mussolini] drew closer to Germany and extended his territorial claims to Tunisia, Corsica, and Djibouti, while eyeing up Savoie and the County of Nice, trade was at its lowest: freight traffic at Breil station that year only accounted for 172 wagons of imports and 232 of exports.” [1: p100]

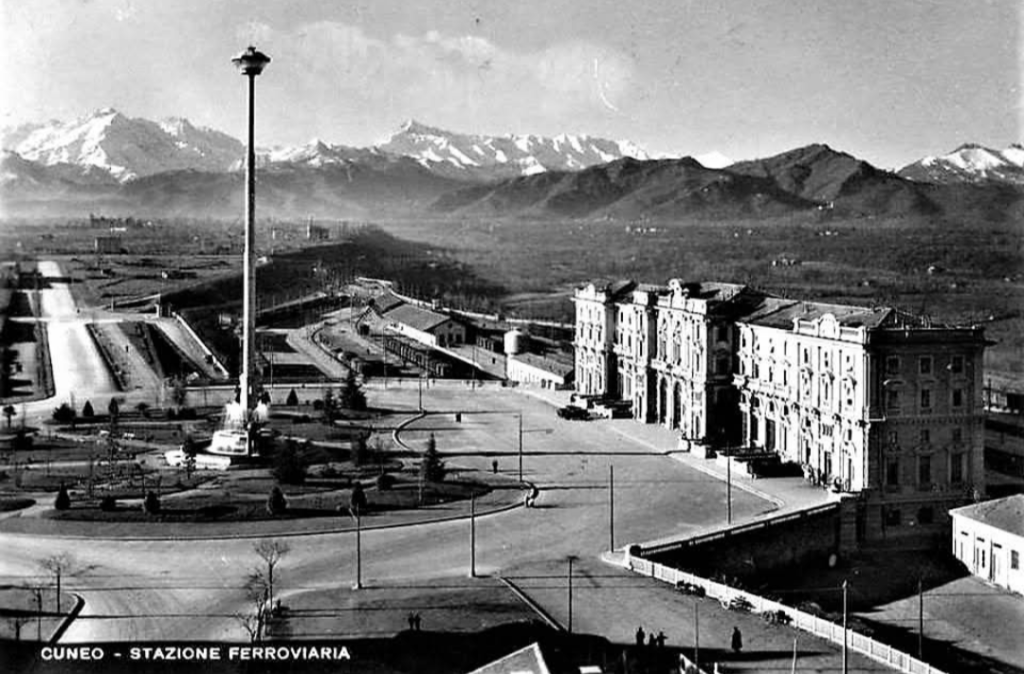

Also within this timeframe, remodelling of the railways around Cuneo was completed. This work was launched in 1913, interrupted by WWI, progressed slowly because budgets were small, and slowed further because of an economic crisis. The construction work was reactivated by the Fascist regime.

The station building was practically completed by the end of the 1920s, and the stationmaster was appointed in 1932. The premises remained empty and unfinished. Tracks had not yet been definitively laid, and the vast premises remained empty.

Banaudo et al tell us that “the monumental passenger building, in the Piedmontese neo-Baroque style, shares similarities with the one erected at the same time in San Dalmazzo di Tenda. It combines brick, stone, and artificial stone; it is decorated with false columns, and triangular and arched pediments. The central pavilion with three doors, overlooking the ticket hall, is framed by two wings with five doors and two side pavilions with three doors. The premises on the ground floor house a buffet, waiting rooms, a royal lounge, numerous offices, while the upper floors are divided into staff accommodation. Since the station forecourt sits above the level of the tracks, the building has three floors on the courtyard side and four on the track side. Two staircases provide access to the platform, a second flight of steps leads to an underground passageway which connects to two other platforms and passing beneath 6 tracks, five of which have platform faces with a sixth providing a central through road. There are also seven shunting and storage through-tracks for freight trains and six sidings on the South side which serve goods sheds and the freight yard.” [1: p102]

At the southern end of the station, a double track led to a site overlooking the Stura River where the new engine shed was located. The depot included an administrative block with a foyer and canteen, two sheds for storing steam and electric locomotives, a workshop with hoist, fifteen tracks, and an 18-metre turntable powered by a compressed air.

More photographs of the Locomotive Depot at Cuneo can be found by scrolling down the results of a search on the Ferrovia Internazionale Cuneo-Ventimiglia-Nizza Facebook Group using this search term: ‘Cuneo Stazione Deposito Locomotive‘. It appears not to be possible to provide this search as a link. One further photograph of the ‘Deposito’ from that Facebook Group is below.

The next article in this series will look at the war years (1939-1945)

References

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 2: 1929-1974; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 3: 1975-1986; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/07/22/the-railway-from-nice-to-tende-and-cuneo-part-1.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/07/26/the-railway-from-nice-to-tende-and-cuneo-part-2.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/08/06/the-railway-from-nice-to-tende-and-cuneo-part-3-vievola-to-st-dalmas-de-tende.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/08/16/the-railway-between-nice-tende-and-cuneo-part-4-st-dalmas-de-tende-to-breil-sur-roya.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/08/25/the-railway-between-nice-tende-and-cuneo-part-5-breil-sur-roya-to-ventimiglia.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/08/29/the-railway-between-nice-tende-and-cuneo-part-6-breil-sur-roya-to-lescarene.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/09/26/the-railway-between-nice-tende-and-cuneo-part-7-lescarene-to-drap-cantaron-railway-station.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/10/07/the-railway-between-nice-tende-and-cuneo-part-8-drap-cantaron-railway-station-to-nice.

- Marco Chitti; A brief visual history of rail electrification in Italy; 2022; via Substack, https://share.google/OLnbh9pPCydeu15W2, accessed on 18th October 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FS_Class_E.550, accessed on 18th October 2025.

- https://www.railpictures.net/photo/845010, accessed on 18th October 2025.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:FS_E.554, accessed on 18th October 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FS_Class_E.432, accessed on 18th October 2025.

- https://retours.eu/en/21-la-littorina, accessed on 18th October 2025.

- https://share.google/images/5AjuS4uUfiehiN4wR, accessed on 18th October 2025.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Littorina_ALb_80.jpg, accessed on 18th October 2025.

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fiat_Littorina, accessed on 18th October 2025.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FS_940_002_1.jpg, accessed on 19th October 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stazione_di_Cuneo_(2).jpg, accessed on 18th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/1AGWYfqjNj, accessed on 26th October 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/17FmVD7YBu, accessed on 27th October 2025

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1P7g6bB2ip, accessed on 27th October 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1Cetzn4vcz, accessed on 27th October 2025.

- http://www.lecomtedenice.fr/Visi_nice/val_roya_tende.html#photo_1, accessed on 13th November 2025.

- https://www.cparama.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=132&t=24479, accessed on 14th November 2025.