Jose Banaudo published a two volume set of books about the historic trams of Nice, “Nice au fil du Tram.” Articles based around the first of these two volumes can be found on this blog.

This is the second in a series looking at the second volume. The first can be found on this link:

The First Generation Electric Tramways of Nice again. Four of the Urban Lines. (Chemins de Fer de Provence/Alpes-Maritimes No. 88)

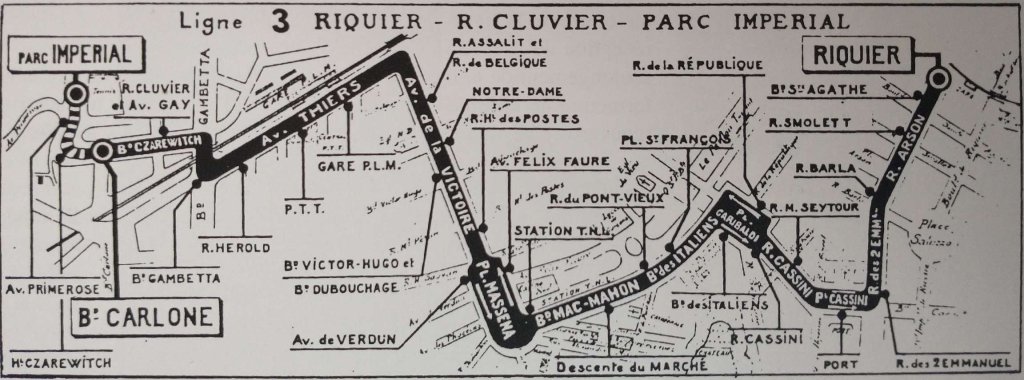

La Ligne de Riquier et du Parc-Imperial

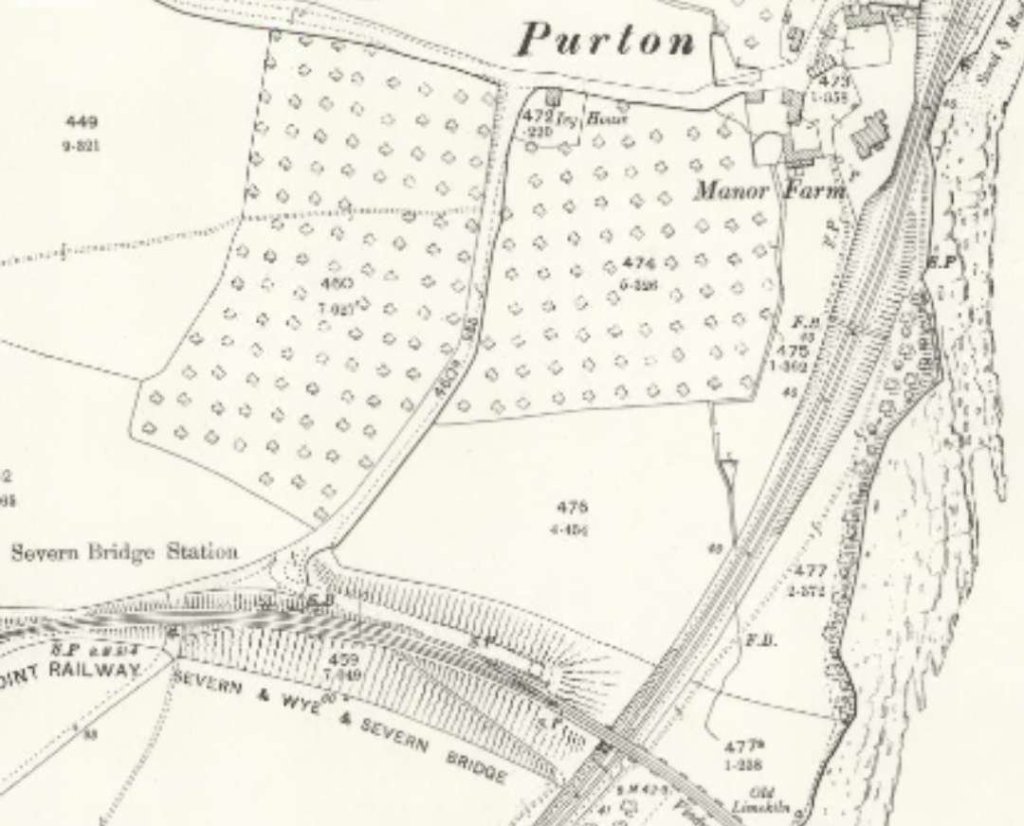

This line was almost entirely double-tracked. It originated on the Place de Riquier (today Auguste-Blanqui), west of the PLM station on the Nice – Ventimiglia line which serves this working-class district to the east of the city. It ran down Rue Arson, passing the depot on Boulevard Ste. Agatha.

Initially, an old building stood out from other frontages along the route and required a short section of single track (304 metres) The building was demolished in 1914 and the single-track section was eliminated. At the intersection with Rue Barbéris, a branch headed east to serve a warehouse. At Rue Barla, the Ligne du Port crossed the rails on Rue Arson. Shortly thereafter, two other branches made it possible to deliver wagons to the Giordan metallurgical plant and the cement warehouse on Rue Lascaris. The line then reached the Eastern corner of the Port, where it joined the Monte-Carlo line and the Voie des Docks towards the Quai des Deux-Emmanuel.

After running along a length of Rue des Deux-Emmanuel, the line turned right onto Place Cassini (now Ile-de-Beauté) where there was a significant tram-halt. In order to make it easier for the trams that had their terminus here to reverse, a complete loop went around the church of Notre-Dame du Port via Rue Rusca, Rue Fodéré and Rue Pacho. At the West end of the square, the tramway passed in front of the monument in honor of President Sadi Carnot, whose bronze bust disappeared during the requisition of non-ferrous metals during the last war, then it went up Rue Cassi to Place Garibaldi. From there, the route was common with other lines on the Boulevards of Pont-Vieux and Mac-Mahon (today Jean-Jaurès), Place Masséna, Avenue de la Gare (today Jean- Médecin) and Avenue Thiers to the PLM station.

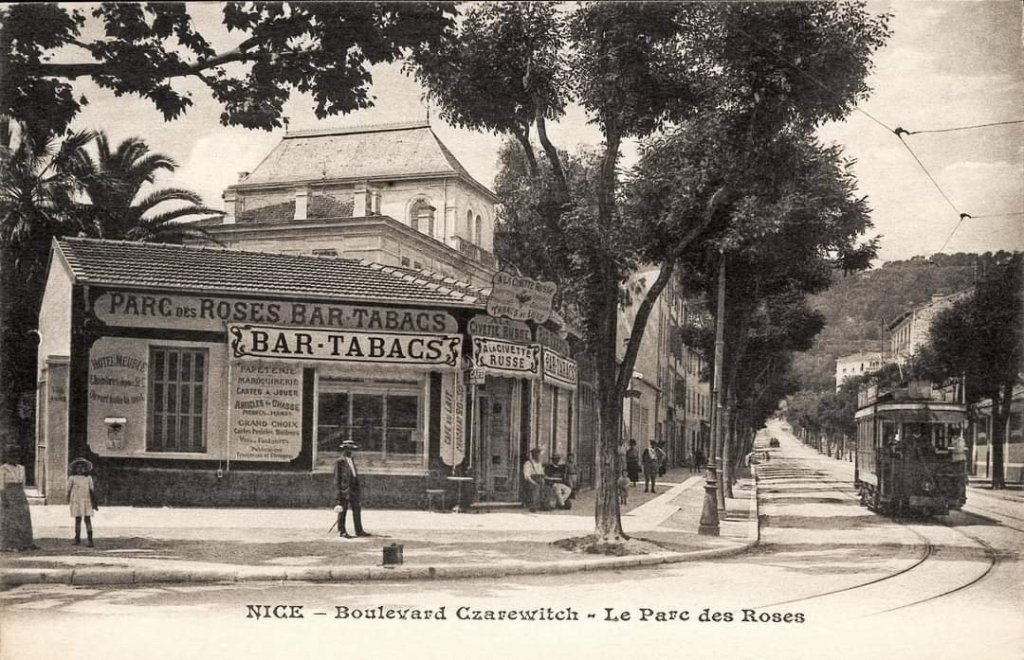

Jose Banaudo continues: “After stopping at the station, the line continued West along Avenue Thiers where a new main post office was installed in 1931 in a large red brick building, in a rather incongruous style in our latitudes. At the intersection of Boulevard Gambetta, the Parc-Impérial line briefly joined the ‘Circulaire’ in order to pass under the bridge of the PLM Marseille-Nice line. Then, it branched off to the left into Boulevard du Czaréwitch (today Tzaréwitch) whose name honors the Crown Prince of Russia, Nicolas Alexandrovitch, who died in 1865 in a villa in this district where the Imperial family used to come stay in the winter.” [1: p22]

Trams then passed in front of the Russian Orthodox cathedral, completed in 1912, and stopped at the crossroads with Rue Cluvier where the double track ended. The urban service terminus was set shortly before the intersection with Avenue de la Tour-Lascaris (today Boulevard François-Grosso).

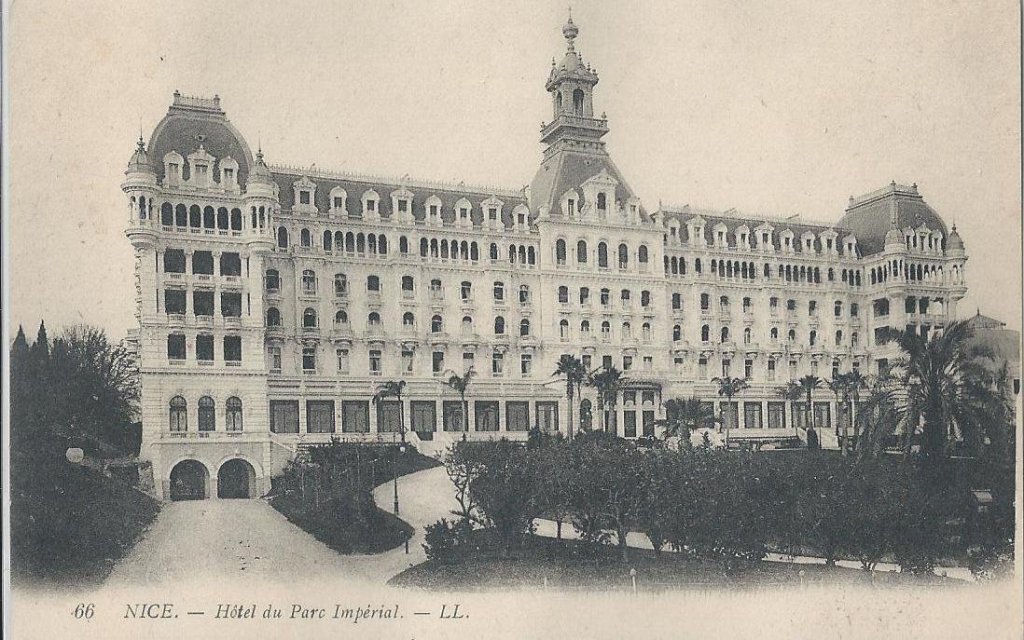

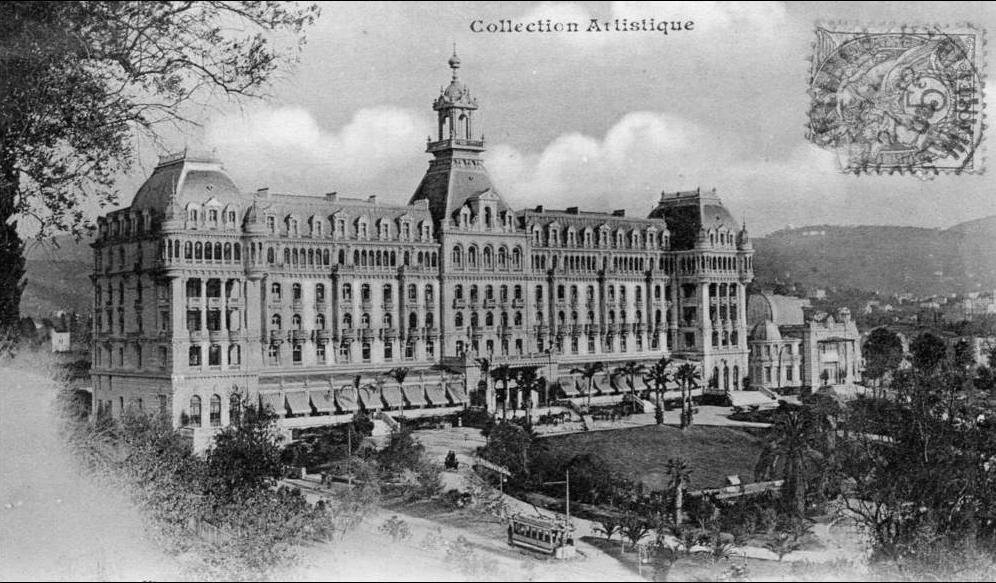

There was a further 529 metres of single-track climbing Boulevard du Parc-Impérial and Avenue d’Angleterre (today Paul-Arène) to terminate at the Southwest corner of the Grand Hôtel du Parc-Impérial.

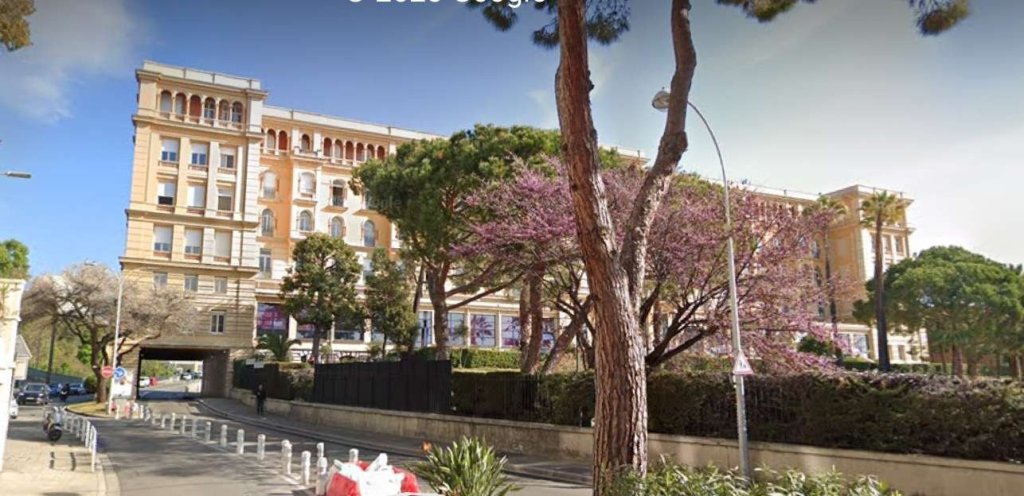

The Hotel opened in 1900 on the property where the Russian Imperial family came for vacation. It was this luxury establishment which had financed the extension of the tramway to its doors. The single-track section was only operated during the tourist (winter) season, from 1st December to 15th May. It disappeared in the post-war years when the hotel found itself in a difficult financial situation leading to its acquisition by the city of Nice in 1926 with a view to transforming it into a school.

The Riquier-Parc-Impérial line linked a working-class district and a residential area in the hills, passing through the main transfer points of the urban network: the Port, Places Garibaldi and Masséna, then the PLM station. The route was used by services from Mont-Boron to the PLM station which used it after running between Mont-Boron and the Port on the Monte-Carlo interurban line. In the 1934 redesign, this route disappeared with the exception of the Riquier – Port – Garibaldi section which was integrated into the new line No. 7. Line No. 7 was the last line served by trams, running until 10th January 1953.

La Ligne de la Gendarmerie, Pasteur, St. Pons et St. Andre

This line linked Place Masséna with St. Andre.

From the TNL station on Place Masséna, the double-track line ran along Rue Gioffredo. Initially, this route also served the Monte-Carlo and Levens lines, and then, from 1934, all services serving the east of the city took this route. After passing behind Masséna high school and Voeu church, trams for St. Andre met the line arriving from the PLM station via Rue Tonduti-de-L’Escarène, and then saw the interurban lines turn away to the right via Rue Defly towards Place Garibaldi.

Until the end of the Masséna – Garibaldi route via the left bank of the River Paillon in 1934, Rue Defly and Pont Garibaldi were only used by interurban services to Levens, Villefranche, St. Jean-Cap-Ferrat, Beaulieu and Monte Carlo.

At the end of Rue Gioffredo, the service connection to the Cimiez line turned away to the left and St. Andre trams turned right into Boulevard Carabacel where there was a connection to the construction materials warehouse of Charles Véran. At Place Carabacel (today Jean-Moulin), tracks to Pont and Rue Barla turned away to the right. The tramway to Levens rejoined that for St. Andre after having detoured through Place Garibaldi.

The line then ran along the right bank of the River Paillon, then only lightly developed, via the quays of Place d’Armes and Pasteur (today Galliéni and Lyautey). After passing under the PLM Nice – Ventimiglia railway, trams arrived at the stop serving the Gendarmerie, which was the terminus for several years. From there, the single track followed the shoulder of the roadway on land recovered from the river bed. Two branches served a fuel trader and the Andréis steel construction works. The tramway then ran under the bridge of the PLM Nice – Cuneo line, after which there was a passing loop at the stop called ‘Vésubie’, at the intersection of avenue Florès. It then ran alongside the district named Pasteur after the large hospital built in 1913, and where a velodrome brought great entertainment on race days. The valley narrowed here, at the foot of the hill where the monastery of Cimiez and the ancient abbey of St. Pons stand. Two stops with passing loops followed, at St. Pons-Octroi and St. Pons-Asile, the latter serving the psychiatric hospital Ste. Marie.

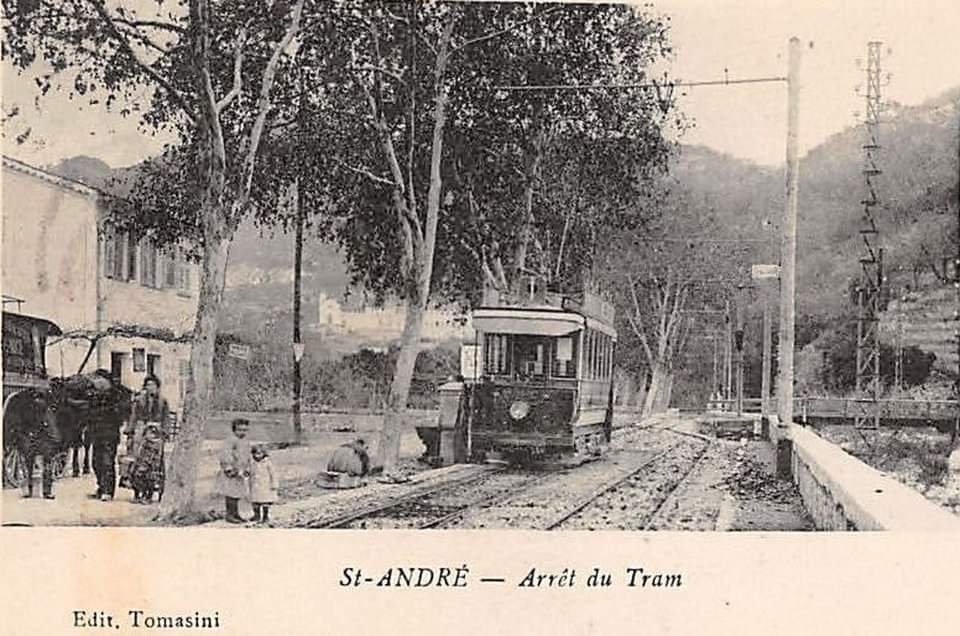

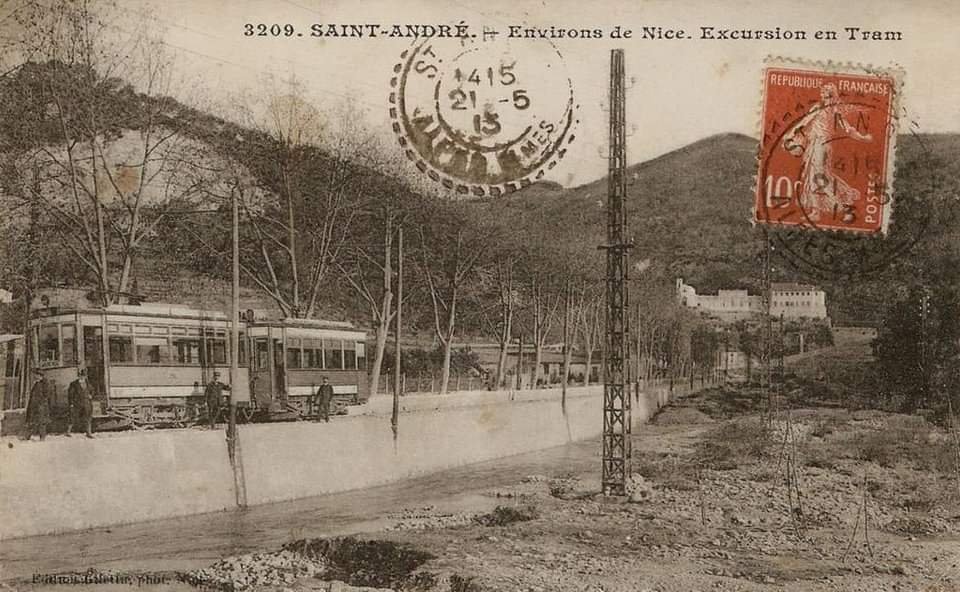

Shortly after this narrow passage where the ligne de Contes could be seen on the other bank of the river and where some services continued towards Levens, the St. André tramway left the Paillon valley to follow the Chemin de Grand Communication No. 19 (currently Departmentale No. 19) into the narrow valley of the River Banquière to reach the terminus at St. André.

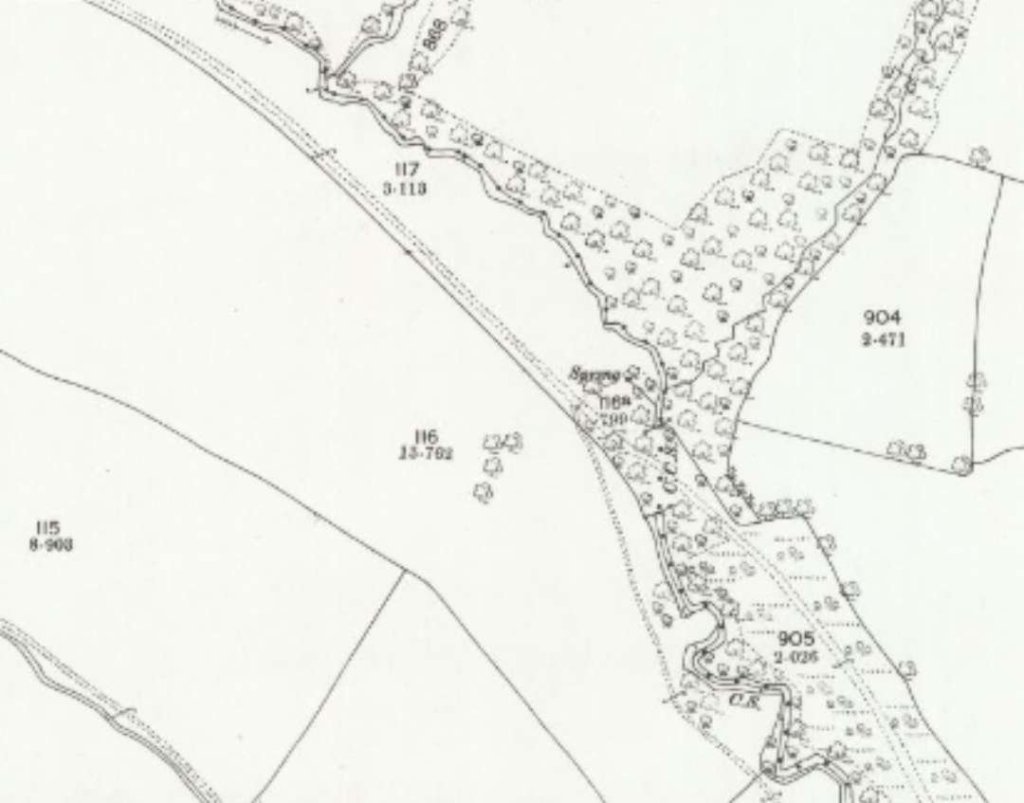

I have been unable to locate these two views in relation to the landscape around St. Andre de la Roche in 2023. However, one group of buidlings does appear on the image below.

This line closed in September 1948 in favour of a replacement bus service.

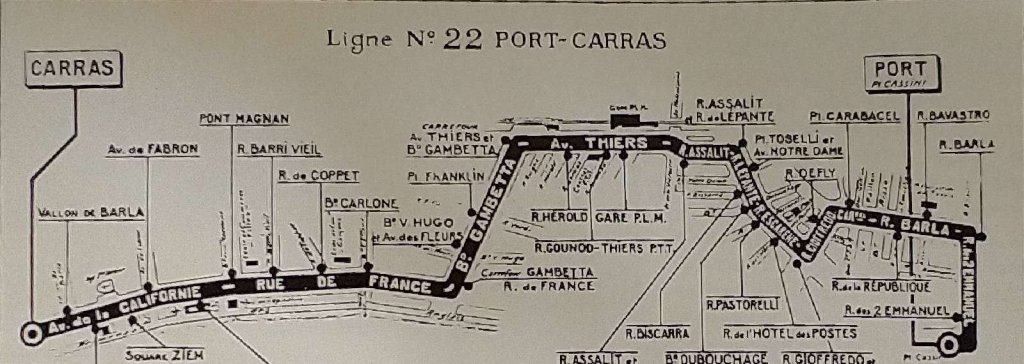

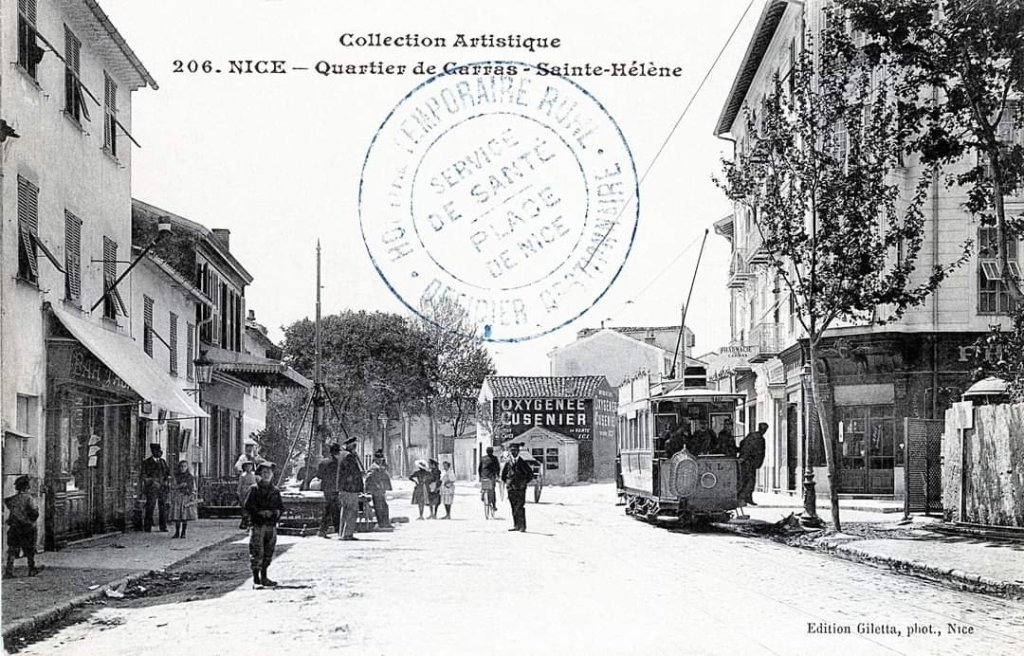

La “Rocade” des Rules Barla, De Lepante et Assalit (Sauzzo – Gare PLM – Carras)

This route, was created to link the East to the West of the city of Nice via the main railway station. The location of its termini was altered several times. Intentionally, it served less busy streets.

At its Eastern end it originated not far from the Port in the Riquier district, on Place Saluzzo (today Max-Barel) which since 1908 has been the starting point of the “Moyenne Corniche” towards the Col de Villefranche. From there, a dedicated route led via Boulevard Imperatrice-de-Russie Boulevard (today Lech-Walesa) to warehouses which were used by the army during the First World War.

The double track followed Rue Barla in a westward direction where, just 87 m from its starting point, it crossed Rue Arson and the line going down from Riquier towards the Port. Shortly after, the tram passed in front of the tobacco factory.

At the crossroads with Rue de la République, it crossed the line of Abattoirs, La Trinité and Contes, and then crossed the River Paillon on Le Pont Barla. Banaudo says that this was, “a beautiful structure with three cast iron arches in a style similar to that of the Garibaldi bridge nearby.” [1: p27]

Now on the right bank of the Paillon, the line met La Ligne de St. Pons which it followed for a short distance along Boulevard Carabacel and Rue Gioffredo. [1: p27]

Arriving at the intersection of Rue Tonduti-de-L’Escarène, the tramway branched off to the North taking this fairly narrow street to Place Sasserno. From there, it entered Rue de Lépante, which commemorates “a terrible naval battle against the Turks in 1571 in which ships crewed from Nice participated.” [1: p27]

Turning sharply to the West, the line followed the narrow Rue Assalit at the end of which it came out at the end of Avenue de la Gare (today Jean-Medecin). It crossed the tram tracks there and entered Avenue Thiers, stopping in front of the PLM station before following Avenue Thiers along its entire length to the intersection with Boulevard Gambetta. At Boulevard Gambetta, the trams turned South towards the crossroads of Rue de France and then turned West to run along the same route as lines to La Madeleine, La Californie and Cagnes to a terminus at either Pont-Magnan or at Carras depending on its year of operation. [1: p27]

This line closed in November 1948 in favour of a replacement bus service.

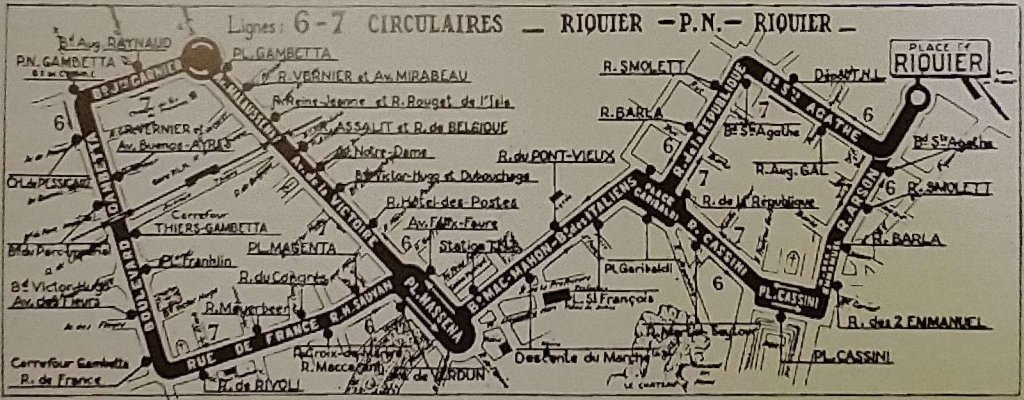

La “Circulaire” Par le Passage a Niveau (Ste. Agathe – Passage a Niveau Gambetta)

Of all of the lines in the Nice tram network, this line was the most varied. Over most of the route, it followed tracks used by other lines. The only exceptions, Banaudo tells us, “being the lengths between Gare du Sud and PN Gambetta and at the Gambetta / Czaréwitch crossroads.” [1: p30]

Banaudo goes on to say that the route, “lost its circular character in 1934 with the elimination of the north-south axis via the avenues, but part of its route was taken up later to create line 7 which was the last served by trams, closing in 1953.” [1: p30]

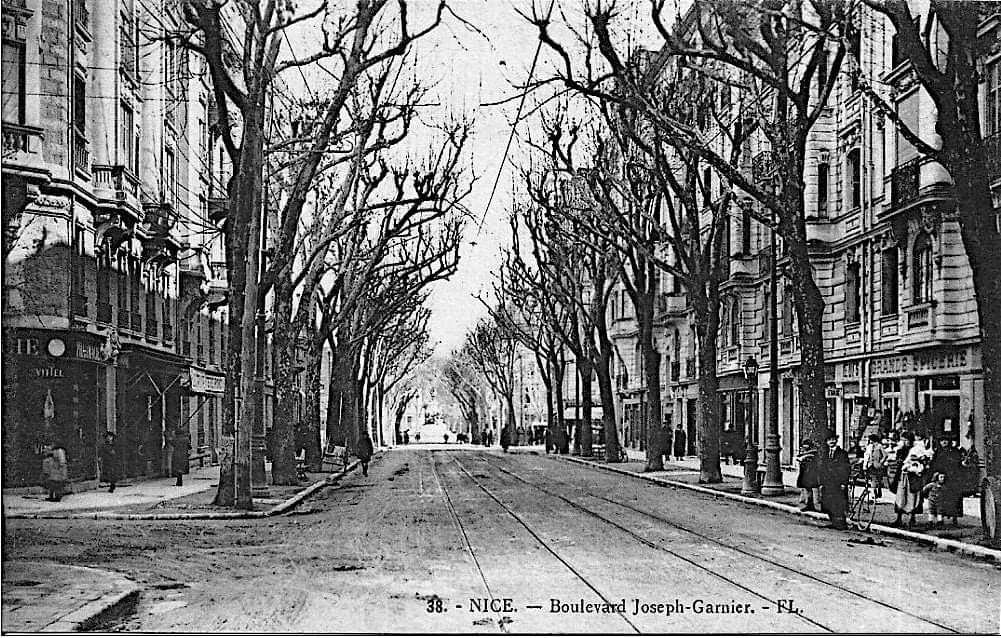

Initially, the ligne “Circulaire” services left Place Masséna along Avenues de la Gare (now Jean-Medecin) and Malaussena to Place Gambetta (today Général De Gaulle) in front of the Gare du Sud. “There, the route branched off to the west taking Boulevard Joseph-Garnier to the level crossing of the Nice – Digne and Nice – Meyrargues lines of the Chemins de fer du Sud de la France (SF). The TNL double track crossed that of the SF by a quadruple crossing on which traffic was governed by instructions common to the two companies. Here, the trains had priority over the trams: an announcement by electric bell warned the barrier guard of their approach, who closed the signals for the tram and then stretched four chains across the road to stop traffic. In the north-west corner of the level crossing, a TNL track connected to a long siding belonging to the SF, through which the goods convoys commuting from the Port were pushed back towards the goods yard of the Gare du Sud.” [1: p30]

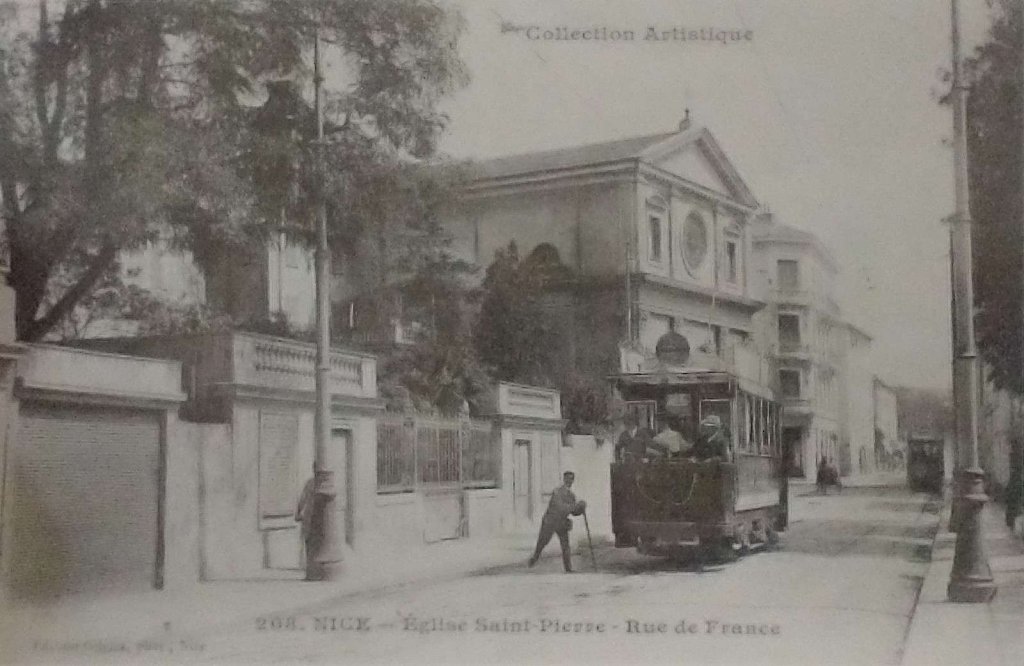

After this the “Circulaire” ran South along Boulevard Gambetta. At the crossroads of Boulevard Czaréwitch (today Tzaréwitch), the line to the Parc-Impérial left to the West. The “Circulaire” then passed under the railway bridge. After which, the lines towards the PLM Station branched off to the East onto Avenue Thiers. Some distance further South, the “Circulaire” turned left (East) into Rue de France, joining the route used by trams serving La Madeleine, Carras and Cagnes and returned to Place Masséna.

Banaudo tells us that, “Later, the route was extended eastwards in three stages: – First to the Port via Boulevards Mac-Mahon and du Pont-Vieux (today Jean-Jaurès), Place Garibaldi and Rue Cassini. Then, an additional loop was added to this circuit: from the Port, it went up Rue Arson to Boulevard Ste. Agathe, running along that street to reach Rue de la République and then Place Garibaldi.” [1: p30]

A third short “extension allowed Place de Riquier to be served, which the tramway reached in one direction via the Port and in the other via Boulevard Ste. Agathe.” [1: p30]

This line finally closed in January 1953 in favour of a replacement bus service.

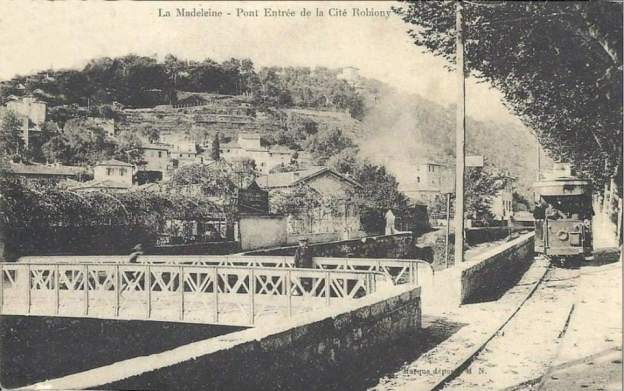

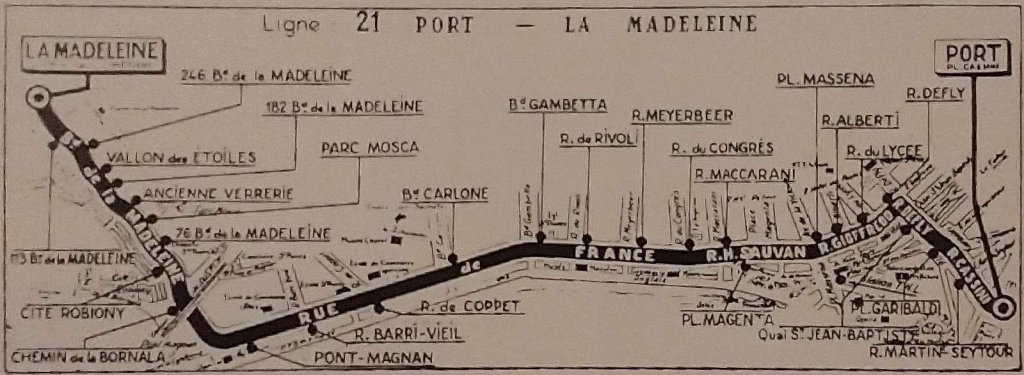

La Ligne de la Madeleine (Masséna – La Madeleine)

The last line to open in Nice’s urban tram network served La Madeleine running initially from Place Masséna but it’s Eastern terminus changed on a number of occasions. First to the Port, then Abattoirs and finally La Trinité Victor.

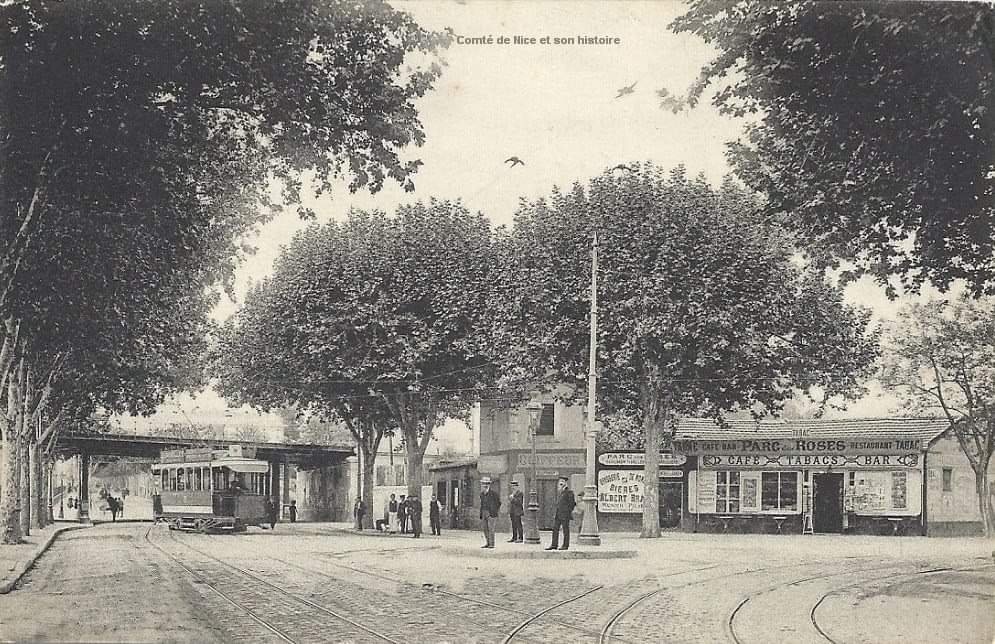

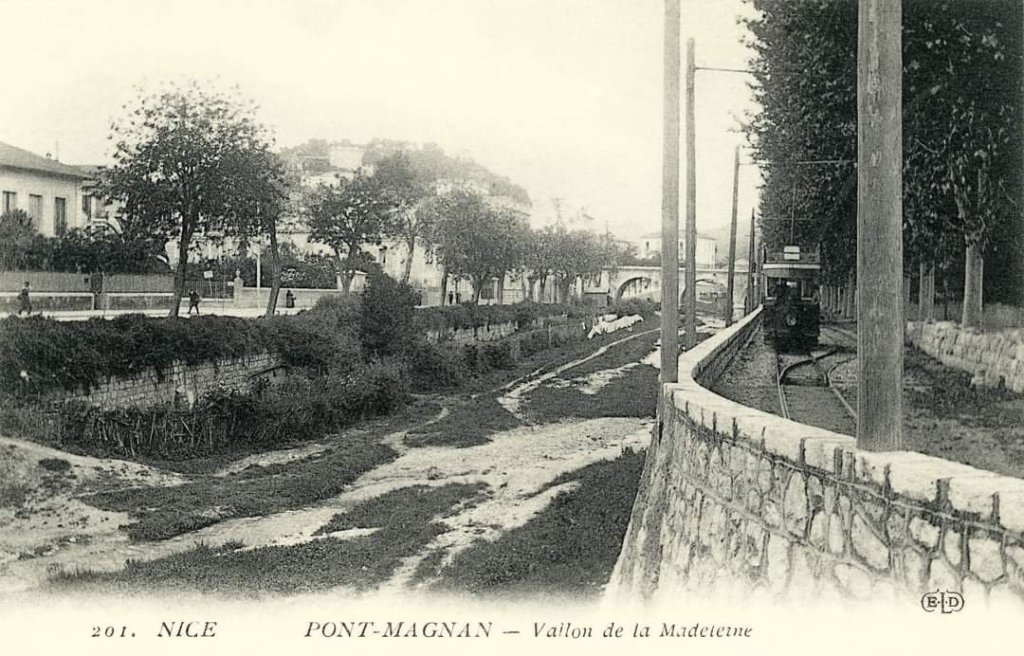

Departing from Place Masséna, the tramway first the main East-West artery heading towards Carras and Cagnes. At Pont Magnan it turned North and became a single-track route. A passing loop was installed just to the North of the junction.

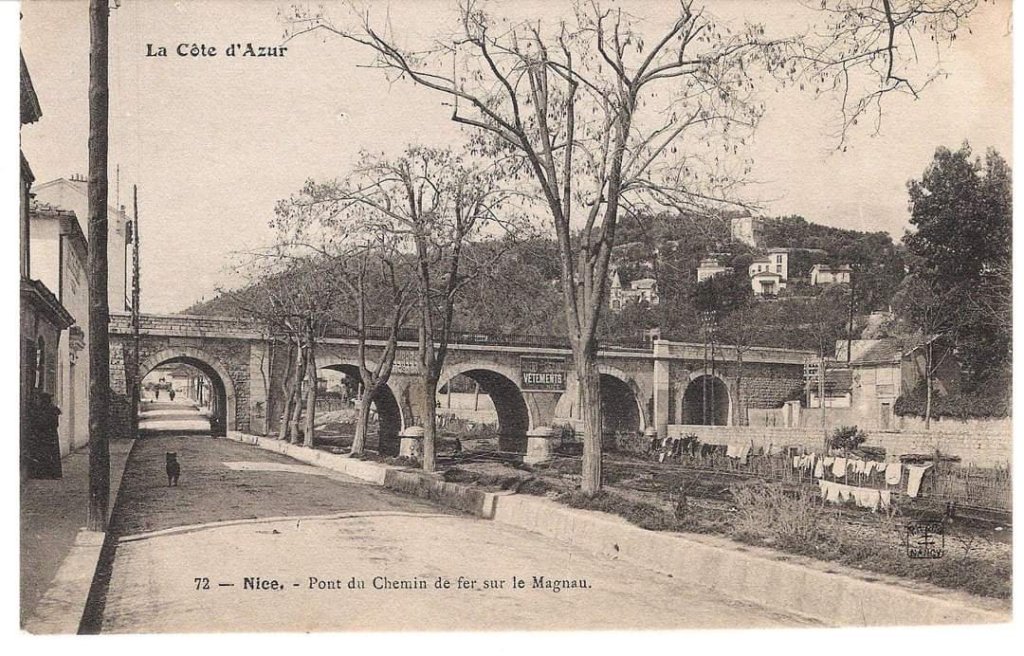

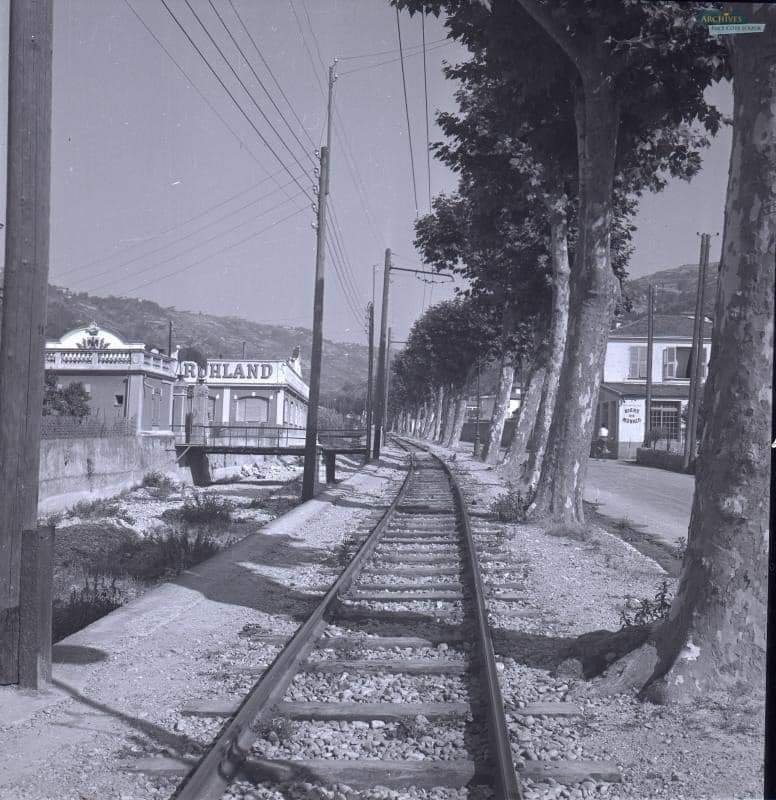

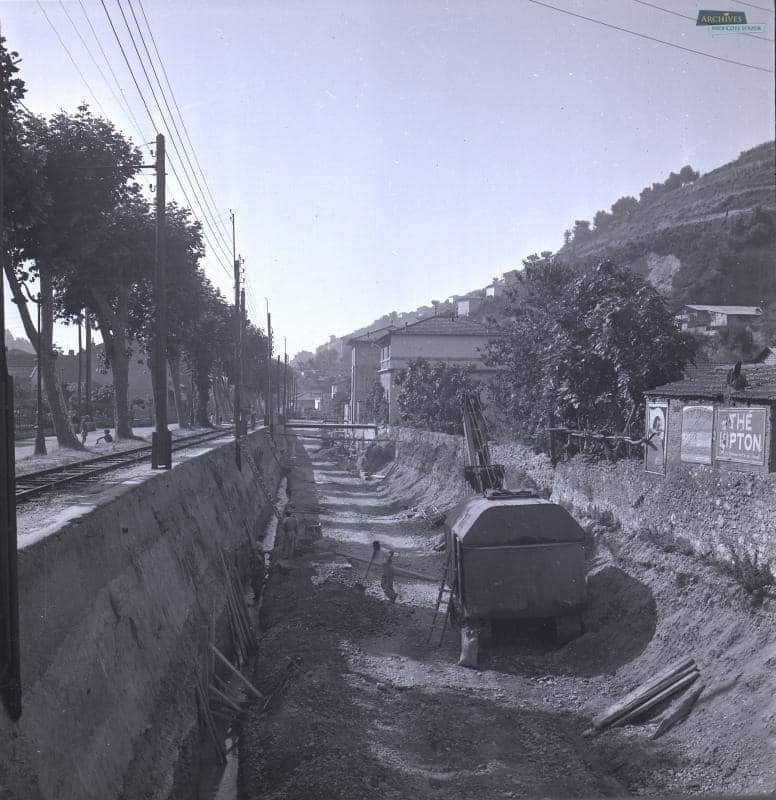

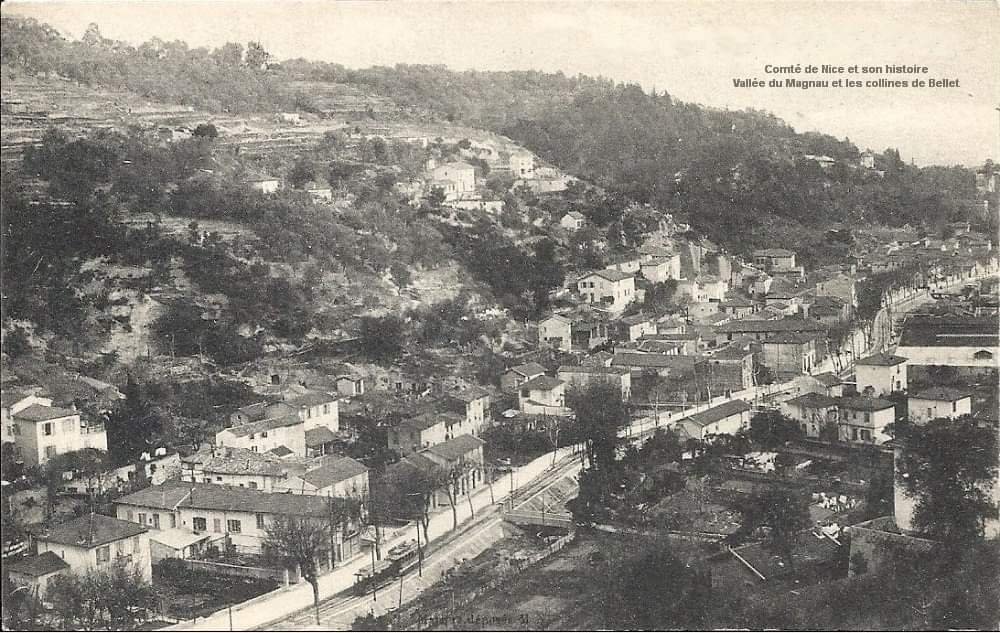

Passing under the PLM Marseille – Nice railway line, the track ran along the left bank of the River Magnan, between Boulevard de La Madeleine and the river. Jose Banaudo tells us that the line “takes its name from the silkworm breeding industry … which flourished in this sector until the end of the 19th century.” [1: p33]

The Magnan valley, then a relatively sparsely populated district on the edge of the city, justified its tram service due to the presence of “numerous craft workshops and small factories such as a mechanical piano factory, a glassworks, a biscuit factory, a button factory and several laundries. These establishments also left their names on the tram stops, and later on the bus stops.” [1: p33]

“On Sundays, the activity of the workshops was replaced by renowned restaurants with dance floors and boules. Many city dwellers came to spend a relaxing day in the countryside, which inevitably included an excursion to the “Trou des Etoiles”, a natural cave, 35 m deep at the base of Ventabrun hill which was then mentioned in the most prestigious tourist guides.” [1: p33]

Passing loops sat in front of two restaurants, “Chalet des Roses” and “Les Orangers”. The terminus was in the Place de La Madeleine (today Alexandre-Blanchi) below the church, the cemetery and la gare Sud-France station which served the village.

This line closed in December 1951 in favour of a replacement bus service.

References

- Jose Banaudo; Nice au fil du Tram, Volume No. 2: Les Hommes, Les Techniques; Les Editions de Cabri, Breil-sur-Roya, France, 2005. This is a french language text.

- https://cartepostale-ancienne.fr/image/data/nice2/nice%20anciennes%20cartes%203%20-%20Copie%20(2).jpg, accessed on 18th September 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3653570808222095, accessed on 18th September 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3603827463196430, accessed on 19th September 2023.

- https://www.geneanet.org/cartes-postales/view/5006424#0, accessed on 19th September 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/2772946732951178, accessed on 19th September 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/1767626043483257, accessed on 23rd September 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3627417797504063, accessed on 23rd September 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3258725034373343, accessed on 23rd September 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3254264148152765, accessed on 27th September 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3660228510889658, accessed on 27th September 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/1747300928849102, accessed on 27th September 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/2999148096997706, accessed on 27th September 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3608755489370294, accessed on 27th September 2023.