Tramway de Nice et du Littoral

The Tramway de Nice et du Littoral was a network of trams which served Nice and the communes of the department of the Alpes Maritimes between 1878 and 1953. These notes have been culled and translated from the French Wikipedia site as noted in the references below.

The Paris Financial Corporation , together with the Society of Public Works and Buildings constructed a network of horse tramways in Nice which was finished in February 1878 and started service on 3rd March that year.

The network comprised four lines: Place Massena – Pont Magnan; Place Massena – Abbatoirs; Place Massena – Saint Maurice; Pont Magnan – Sainte Helena. These were single track lines of standard gauge (1440 mm).

The network was leased to the Compagnie Générale des Omnibus de Marseille, on 4th September 1879. And after that company failed the ‘Société nouvelle des Tramways de Nice (SNTN) took over running the system in 1887.

In addition, in 1895, Compagnie Anonyme des Tramways Électriques de Nice-Cimiez was awarded a concession for a tram line between the Rue de l’Hôtel des Postes and Cimiez zoo. That line was built to a gauge of 600mm and used electric traction batteries because of its difficult route. It was commissioned on 24th November, 1895.

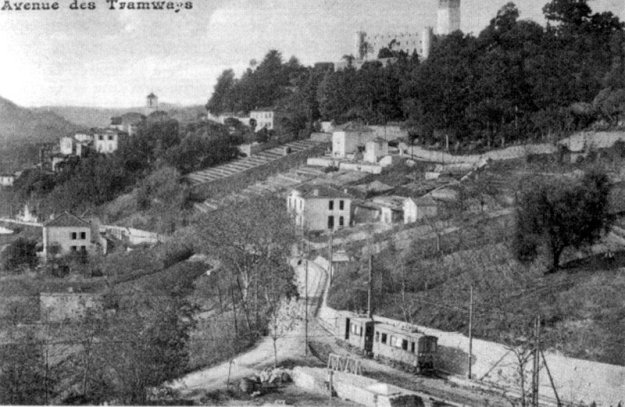

Place Massena was at the centre of the network and the other two photos show trams on Le Rue de la Gare

La Compagnie des Tramways de Nice et du Littoral (TNL)

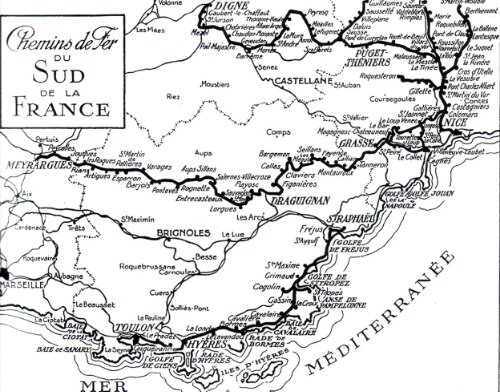

This company was created to replace the old “Société nouvelle des Tramways de Nice”, on 16th September, 1897. Its purpose was to: create a network along the Cote D’Azur from Cagnes to Menton , with a branch to the port of Nice and to Contes; it was to electrify the urban network to resume operation to Cimiez which had lapsed.

The lines opened in the following order: Nice – Cimiez , 13th January, 1900; Place Massena – Villefranche-sur-Mer, on 1st February 1900;, Nice – Saint Laurent du Var, 7th February, 1900; Port – Saint Maurice, 12th February 1900;c Nice – Cagnes, 14th March 1900; Nice – Contes, 2nd June, 1900; Nice – Beaulieu, 3rd June, 1900; Magnan – Saluzzo, 3rd November, 1902; and Gambetta – Massena (via Avenue Joseph Garnier), also on 3rd November 1902.

The network centred on the Place Massena where most lines converged. All the lines were electrified by underground gutter and a fleet of 100 trams was used.

Compagnie des Tramways de Monaco

The Compagnie des Tramways de Monaco was founded in 1897 by entrepreneur Mr. Crovetto Monaco. He obtained the concessions on these lines: Place d’Armes – Saint Roman, opened May 14, 1898; Gare de Monaco – Government Square, opened March 11, 1899; Casino – Gare de Monte-Carlo, opened May 3, 1900.

In 1900, the network was linked to the LNP (Line Nice – Monte Carlo). In then in 1908, the company was absorbed by the company TNL. However,by 1931 trams had disappeared completely from the principality.

La ligne de Monaco et Menton

This line connects Nice, Villefranche, Beaulieu, Monaco and Monte Carlo by a linee along the Basse Corniche. It opened on 7th November 1903. An extension from Monaco to Menton Opened on 20th December, 1903. The line connected with with the network of urban tramways in Monaco.

Extensions

Extensions were built over time, either to the departmental network or the urban network.

Departmental network

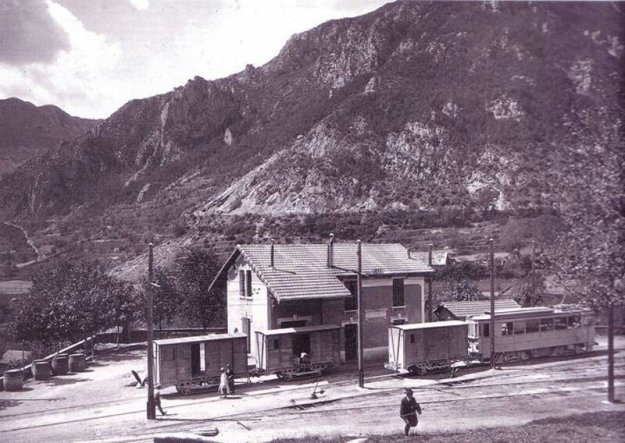

The departmental tram network comprised 14 lines to be built, assigned to the LNP or to the Chemins de Fer du Sud . The latter through its subsidiary: Les Tramways des Alpes-Maritimes (TAM).

The LNP obtained the concession of the following lines: Le Pont-de-Saint-Jean (commune de A further route – La Grave de Peille – L’Escarène – was never built.Villefranche-sur-Mer ) – Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, which opened on 7th December 1907; Nice – Levens , opened 15th June, 1908; Cagnes – Antibes and Cap d’Antibes, opened on 1st February, 1909; Contes – Bendejun , opened on 1st February, 1909; Pont de Peille – La Grave de Peille, opened in 1911; Menton – Sospel: Menton – Villa Caserta, opened in October, 1911 and Villa Caserta – Sospel, opened in April, 1912.

The tram to Antibes linked with the network of trams in Cannes.

Urban network

Magnan – La Madeleine , 27 April 1908

Line from Menton to Sospel

This line from Menton to Sospel is open April 15, 1912, as part of the construction of the departmental network. Its length is 18 km. It marks the end of the extension of the LNP. See http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tramway_de_Menton_à_Sospel for more information.

The apogee of the tram network

The growth of the population of Nice and the surrounding towns and villages led to a rapid development of the network. In 1930, the LNP network consisted of 144 km of track, and had a fleet of 183 drive trams and 96 trailers.

Developments and end of the network

However, very soon the tramways suffered strong competition from road vehicles and by 1934 the coastal routes and the suburban network, including the routes to the various villages and communes had entirely disappeared. The municipality also gradually closed the urban lines, so that by 1939 there were only four lines left: Line 3: Abattoirs – La Madeleine Trinity Victor; Line 9: Port – Saint Augustine; Line 22: Gare PLM – Carras; Line 35: Rue Hôtel des Postes – Cimiez.

During the Second World War, two lines were reopened as all buses were requisitioned: Line 6: Passage à niveau – Pasteur; Line 7: Passage à niveau – Riquier. The tramways to Contes and La Grave de Peille also reopened.

At this time the network had 48 drive trams and 22 trailers (some additional drive vehicles were also built in 1942).

After the Second World War, the trams were replaced by trolleybuses and the last tram ran on 10th January 1953.

References

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tramway_de_Nice_et_du_Littoral

“Les tramway de Nice et du Littoral,” Connaissance du Rail , No. 320-321, mars 2008

Jean Robert, Nice to Chamonix Secondary networks Alpes-Maritimes, Montreuil. Impr. Time, 1961, p101.