This blog is based on the text of the book written in French by Jose Banaudo: Nice au fil du Tram: Volume 1, Histoire; Les Editions du Cabri, 2004. The notes below are intended to promote a better understanding by an English audience of the tramways of southern France.

Difficult recovery

Like all transport companies, TNL faced post-war years of economic, social and material hardships. All developments of the network were suspended. The political upheaval brought tourism to a halt. Habits were changing and other forms of transport stole passengers from the trams. Inflation increased the price of materials and supplies when urgent repairs were required after years of neglect.

Employees who had shown great loyalty during the conflict started to defend their rights. They years after the first World War were ones of social unrest. in May 1920 the police and army occupied the Ste. Agathe depot to prevent striking workers disabling the network,

The constant search for savings was prioritised above the quality of the service to customers, especially on the wider departmental lines where the service had been reduced to two or three trips a day on certain sections during the war years. Not only did the service not improve, but in some cases it was further diminished. For example, on La Grave-de-Peille route there was only one round trip per day in 1919. In the face of protests raised by this failure, an improved service was introduced the following year.

The urban service also left much to be desired. In Nice City Council, the discontent was such that for the first time some elected officials proposed to replace the trams with buses.

Expansion projects of the departmental network

At Levens, work on the extension towards the village continued at a very slow pace during the war. The formation had been completed by 1917, including the curved tunnel, but the terms for moving the terminus facilities were still unresolved between the department and the company. The tunnel leading to the village of Levens, the structure was completed but never used. No tracks were laid through the tunnel. [2]

On the line from La Pointe-de-Contes to L’Escarene, work resumed at the end of 1919.

In the first half of the 20s, the development of the departmental network was still on the agenda for the Alpes-Maritimes General Council. However, persistent economic difficulties discouraged public investment in trams to rural areas where road transport now seemed to offer a more flexible and less expensive solution. The commissioning of new Haut-Var and Esteron lines of the TAM network proved to be a big mistake, the lines were not viable from the beginning, this reinforced an evolution towards road transport.

Even with most of the work complete, the TNL began to wonder whether it was viable to complete and maintain the routes into Levens village and between La Pointe-de-Contes and L’Escarene.

The work on these new links was postponed. As were two other projects planned by the TNL: the establishment in Menton of a TNL passenger and goods station closer to the port, and an underground crossing of the Monaco principality. It became clear very quickly that these projects would not be viable, given the deficits being experienced on the other departmental lines. New agreements were made with the local authorities but these only brought a brief stay of execution for the least remunerative lines which it had been designed to preserve. [3]

A first restructuring of the urban network

The TNL obtained authorisation, on 6th July 1920, to introduce multi-tier pricing by dividing each line in two, three or four sections, depending on the distance traveled. From 1st January 1923, all the lines of the network were renumbered and their number placed prominently on a color disc at each end of the tram. Nos. 1 to 16 designated urban lines. Nos. 20 to 24 were applied to services on the line to Monte Carlo; Nos. 26 to 30 to those to the valleys of Paillons; Nos. 31 to 34 to those on the line to Antibes and du Cap; Nos. 41 to 46 to the Monte-Carlo and Menton group of lines.

Stops were classified in two categories, fixed and request, which a few years later were designated by red and green plates.

Private entrepreneurs were equipping themselves with trucks and buses. Initially they provided links to the tramway and railway networks and did not act in competition with the trams. Banaudo reports that as early as 1921, the Société Anonyme Nicoise de Transports Automobiles (Santa) opened a Nice – La Turbie line via the Grande Corniche and a Nice – Colomars circuit through the hills, with the financial support of the department and the city of Nice.

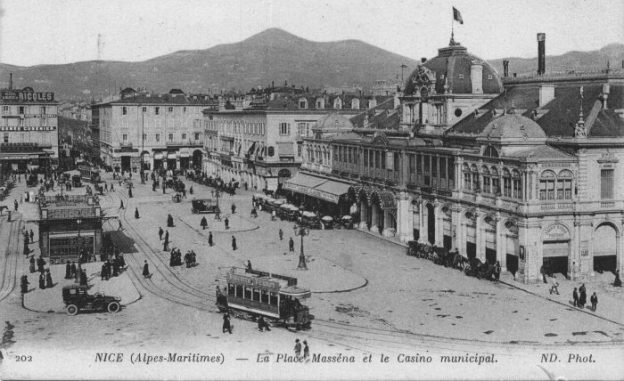

Urban buses appeared in Nice on 28th May 1925 on the Massena-St. Sylvestre line via Jospeh Garnier and St. Barthelemy boulevards (now Auguste Reynard). The TNL operated this first service with road buses. [4]

A second service was inaugurated by the TNL between Saluzzo – Caucade by Dubouchage, Victor-Hugo and Gambetta Boulevards, on 5th October. In May 1926 the terminus of this line was moved to Place Masséna.

As the first buses appeared, the tramway network began to contract. More of that in future articles.

Jose Banaudo gives the following details about the TNL in 1927 which come from the Ministry of Public Works [5] …….

STATISTICS T.N.L. 1927

The TNL operated 141 km of lines, divided as follows:

- Urban network: Nice 26 km (excluding common trunk routes).

- Monaco network 5 km.

- Coastal network 50 km.

- Departmental network 60 km.

The staff is composed of 1373 people, 14 of whom are in administration, 846 in movement, 323 to the equipment and 190 to the track.

The fleet of rolling stock includes 17 freight tractors. 175 power units a travellers. 96 passenger trailers and 162 freight cars.

Trams travelled 5,437,583 km during the year, including 4,164,884 on the urban network, 984,534 on the coastal network and 288,165 on the departmental network .

The total number of passengers carried was 35,416,562. of which 31,680,850 on the urban network. 2,976,441 on the coastal network and 759,271 on the departmentai network.

The total volume of goods transported is 489,689 tonnes of which 299,239 were on the urban network. 148,376 on the coastal network and 42,074 on the departmental network.

Revenues amounted to 24,521,671 francs, including 22,080,605 francs in passenger traffic, 2,286,958 in freight traffic, and 154,108 in miscellaneous revenue. The expenses amount to 22,597,515 francs. i.e. a profit of 1,924,156 francs and a total cost/income ratio of 0.92. But it must be taken into account that only the urban network allowed this level of return to be reported. The coastal lines recorded a deficit of 453,771 francs and a coefficient of 1.1, while the departmental network was subject to a déficit of 431,971 francs and a coefficient of 1.36. These figures pointed forward to likley closures on lines outside the conurbation.

During the year, 925 accidents were recorded, including 6 derailments, 539 collisions with cars, people or animals, and 380 miscellaneous accidents. The overall toll was 4 killed (1 traveller and 3 third parties) and 114 wounded (12 workers. 68 passengers and 34 third parties).

References

- Jose Banaudo; Nice au fil du Tram: Volume 1, Histoire; Les Editions du Cabri, 2004, p78.

- Jose Banaudo; Nice au fil du Tram: Volume 1, Histoire; Les Editions du Cabri, 2004, p79.

- Jose Banaudo; Nice au fil du Tram: Volume 1, Histoire; Les Editions du Cabri, 2004, p80.

- Jose Banaudo; Nice au fil du Tram: Volume 1, Histoire; Les Editions du Cabri, 2004, p81.

- Jose Banaudo; Nice au fil du Tram: Volume 1, Histoire; Les Editions du Cabri, 2004, p82.

Pingback: The First Generation Electric Tramways of Nice again. Four of the Urban Lines. (Chemins de Fer de Provence/Alpes-Maritimes No. 88) | Roger Farnworth