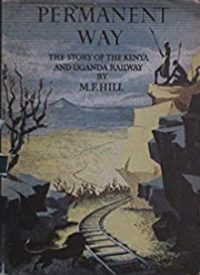

I recently picked up a copy of each of the two volumes of ‘Permanent Way‘ written by M.F. Hill and published in 1949. The first volume [1] is a history of ‘The Uganda Railway’ written in the 1940s when the railway company was known as ‘The Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbours’ and published at the end of that decade under the jurisdiction of the new ‘East African Railways and Harbours’ which was formed to formally include the infrastructure in the modern country of Tanzania.

I recently picked up a copy of each of the two volumes of ‘Permanent Way‘ written by M.F. Hill and published in 1949. The first volume [1] is a history of ‘The Uganda Railway’ written in the 1940s when the railway company was known as ‘The Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbours’ and published at the end of that decade under the jurisdiction of the new ‘East African Railways and Harbours’ which was formed to formally include the infrastructure in the modern country of Tanzania.

Hill’s first volume provides a detailed history of the Uganda Railway until just after the end of World War II.

This is the last article based on Hill’s book. Previous articles in this series based on Hill’s 1949 book are:

Uganda at the end of 19th century and the events leading up to the construction of the Uganda Railway.

The Uganda Railway at the beginning of 20th century.

The Uganda Railway during the First World War

The Uganda Railway in the first 5 years after World War 1

The Uganda Railway: the Gilded Years 1924-1928

The Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbours – The Great Depression and Years of Argument

The Second World War

It was anticipated that, given the international situation in the first 8 months of 1939, followed by the first 4 months of the War, trade would decline significantly to the detriment of the railway. In fact it only declined 2% on the record levels of 1938. [1: p531]

Rates were pushed down to support the economy, but the railway still made a surplus of £208,422. The position was satisfactory with the one exception, provision to cover outstanding loans meant that the railway’s free reserves were only £155,045. This sum was clearly inadequate for the size of the undertaking. [1: p531]

“The railway was not called upon to undertake any major troop movements immediately upon the outbreak of war, because there were few troops to move.” [1: p532]

Initial fears in the British sphere of East Africa were allayed when it was discovered that the feared invasion by Italian forces was not going to happen soon. Mussolini decided to remain ‘non-belligerent’ during the first nine months. This gave East Africa important time to prepare.

“The railway had 3,000 goods wagons and 175 passenger coaches, of which 54 were derelict four-wheelers rescued from the scrap heap. Throughout the war there came no reinforcement of coaching stock, ships or lighters, and only thirteen new engines and 380 goods wagons – in terms of the work done, it was a very small reinforcement. During September and October all the obsolete engines, lying idle and waiting to be sold as scrap-iron, were quickly reconditioned, re-equipped and made ready for service. Fortunately the stock of coal was sufficient for eight months.” [1: p532]

“In general terms, the work of the railway went on in the normal manner, and there was no reduction of African and Asian staff. The earthworks on the realignment between Uplands and Naivasha has been started in August and the work was allowed to proceed. By the middle of 1941 the earthworks, retaining walls and the culverts of the new alignment were completed beyond Naivasha as far as Gilgil. Due to the general shortage of materials, completion of the realignment was then postponed until after the war.” [1: p532]

A reconnaissance survey for the extension of the Nanyuki branch-like into the Northern Frontier Provence was finished by the end of September 1940.

“The total available European man-power in Kenya was 8,998, and soon more than 3,500 men were serving in the armed forces. Of the remainder, rather more than 3,000 were retained in occupations essential to the community. The great majority of the thousand or so European farmers left alone on farms were elderly or of low medical category. They were nobly reinforced by more than 800 European women, many of whom were left alone on farms and many of whom looked after more than one farm. About 6,500 European women, between the ages of sixteen and sixty, were registered for essential service in one form or another, and more than half of them were soon engaged in war-work outside their own homes.” [1: p533]

The railways made a significant contribution to the war effort. “The Nairobi workshops became the Ordnance Main Base Workshops of the East Africa Command. There was a wide range of excellent machinery and skilled men to run it. The shops were the only well-equipped mechanical workshops of any size in East Africa. … In the last 6 months of 1940 more than half the shops’ capacity was devoted to the equipment of the forces. During these months, the maintenance of the railway took second place to an extent which later made it difficult to cope with the arrears of repair. … [At the end of 1939,] the workshops were asked to design and build bodies for 22 motor ambulances, the first of 250 which were eventually built; to manufacture 72 three-inch mortars, 25,000 screw pickets for barbed-wire entanglements, 600 four-gallon water tanks; to make hundreds of stretchers, target frames, supports for anti-tank guns, and to undertake repairs to scores of Bren guns.” [1: p534]

Four Kenyan and seven Tanganyikan coaches were converted to form an ambulance train.

The list goes on and does not need to be repeated here. It is worth noting that in addition to the work at Nairobi, the railway workshops at Mombasa were proving of great value to the Royal Navy and to the Mercantile Marine. A variety of marine repairs were undertaken before the Navy installed their own dockyard facilities. [1: p536]

The transportation and engineering departments began to experience added strain because of the war effort. Between 2nd September and 2nd November 1939, 473 Eritrean deserters and 7,000 Abyssinian refugees had to be moved in 15 train loads, away from potential conflict areas in the North of Kenya. Throughout the war, dramatic increases in both traffic and passengers occurred. “By 1944, the goods traffic had soared to more that 2,000,000 tons, double that of record ore-war years, while the number of passenger journeys, exclusive if special troop movements, rose from about 1,000,000 in 1938 to 2.75 millions in 1944.” [1: p536]

The first clash of arms of the East African Campaign occurred at Notable, in the far North of Kenya. A force of 150 men held the British position in the first of ‘Beau Geste’ against overwhelming odds, around 10 times the ground force strength and Italian Air Power. The eventual retreat of the British force was achieved by stealth and guile.

The Italians began their advance into the Northern Frontier Provence, occupying Dobel and Buna. Another Italian force attempted to invade the Sudan without success. The Italian bombers were billeted within range of both Nairobi and Kilindini, but made no attempt to to bomb either target. [1: p540]

In the Northern Frontier Provence, highly trained British commanded troops soon gained the upper hand. “In Kenya, as in Libya and the Sudan, bluff was a potent secret weapon in the British armoury. The Italian intelligence reports presented a fantastic exaggeration of the real land and air strength. … A few technicians with carefully manipulated wireless sets … so deceived the Italian command that they were convinced of the arrival of an Australian division.” [1: p541]

By the autumn of 1940, the British forces main preoccupation had moved from defence to the mounting of an offensive against Italian Somaliland with The port of Kismayu as a target. [1: p541]

In November 1940, it was decided that the projected offensive “against Italian Somaliland required the building of a railway from Thika, on the Nairobi-Nanyuki line to Garba Tulla, a point in the Frontier Provence roughly halfway between the northern bend of the Tana River and the Uaso Nyiro which flows into the great Lorian Swamp. … The railway was called upon to build the new line, nearly 250 mike’s long, through grim country, as quickly as possible. … By the end of March 1941, when work was stopped due to the unexpected speed of … [the[ offensive, 217 miles of the line had been surveyed, and 117 miles staked out; 81 miles of earthworks had been completed, 7 major bridges were nearly finished, and 12 miles of track had been laid.” [1: p544]

The figures for 1940 were: “including the balance of £119,325 brought forward from 1939, there was a surplus of £554,433 for the year. … Of this sum, £21,000 was allocated as a reserve for the Superannuation Fund, £120,000 was contributed to the Betterment Fund, £300,000 was devoted to be a remission of charges on military traffic and £113,433 was carried forward.” [1: p544]

The rates charged on military traffic were radically reduced. Very low rates for troop movements were introduced. Speaking in 1946, the General Manager said that these rate reductions amounted to a saving to the British taxpayer of over £2 million. In addition, early in the war, a direct gift from the railway of £655,000 was made and an interest-free loan was made to the British Government of £500,000.

“On the other side of the ledger, Kenya colony and the railway were relieved of the contingent liability of £5,592,592 in respect of the original cost of the Uganda Railway on 21st May 1940.” [1: p545]

Total first- and second-class journeys rose firm 46,601 in 1938 to 77,089 in 1940. Increases in the population through settling refugees, the presence of the army, and petrol rationing all contributed to an increase in travel by train. Goods traffic in the year rose to 1,257,158 tons. This produced revenue of £2,184,752, only marginally above the receipts from 1935 which were achieve on transporting 849,795 tons of goods.

Although ton-milesbwere down on both 1939 and 1938 figures, wagon-miles increased from 68 million in 1939 to 74.5 million in 1940. [1: p545]

Public traffic was more evenly spread over the year but instead of significant amount of long-haul goods, there was intensive military traffic with frequent short-hauls and uneconomic wagon loads. [1: p545]

By the end of the year, the strain on the railways increased immensely. In December, 46 special troop trains were run. In addition to the building of the railway towards Garba Tulla, the demands of the Army for sheds and sidings, stores and offices, were so large that a special engineering section had to be set up to cope with military work. [1: p545]

The military campaigns of 1941 which entered the Italian sphere and routed their forces was a great success. According to Hill: “In strategic conception the campaign was bold; in terms of organisation and execution it deserved all praise; and the most remarkable feature was the triumph of the engineers and of transport over immense distances and great natural difficulties.” [1: p550]

In comparison to the battles fought in “Russia, in northern Africa, in Italy and western Europe, the East Africa Campaign was a small thing. But it was the first complete success of British arms on land,band it had a far greater influence on the outcome of the war than us often realised. Of events had turned out otherwise … as once seemed possible and even probable – would it have been possible to hold the Middle East, or the Indian Ocean? If those two vital zones had been lost, the Germans and the Japanese might well have linked hands and the war would have been immeasurably prolonged.” [1: p551-552]

The railway was a major contributor to the war effort, between August 1940 and September 1941, “the railway carried 670,600 tons of military supplies, … special troop trains moved nearly 155,000 soldiers and 22,000 Italian prisoners of war. … Thousands of military passengers travelled by the ordinary train services.” [1: p552]

In 1941, traffic was greatly increased over the figures for 1940: freight ton-miles increased by 87 million; passenger traffic increased to 1,614,156 excluding military passengers (204,522); goods traffic increased to 2,257,761 tons; Kilindini Harbour dealt with 2,101,970 tons (cf. 1938 – 1,261,812 tons).

For the first time railway earnings exceeded £4 million, the surplus including carry forward was £1,217,083 (of which: £365,539 was devoted to remission of charges on military traffic, £321,214 was allocated to the Betterment Fund; £20,000 to the Superannuation Fund; £160,000 to the Rates Stabilisation and Relief Fund; and £350,330 to the General Reserve). [1: p552]

A wagon shortage was a serious problem, exacerbated by a concentration of wagons at depots awaiting shipments; demands for export cargoes at the coast at short notice; uncertain arrival dates for ships; the cancellation of shipments already notified; the use of covered wagons for troop movement; carriage of prisoners of war, third class passengers and livestock. Every effort was made to increase wagon turn-round times which resulted in shorter trains, over-use of coal, increased use of wood (which resulted in the use of less powerful engines0. [1: p552]

Six new Garratt engines in December 1940 and throughout 1941, was a welcome improvement in haulage power but the Garratts were unable to operate with wood fuel. The rapid increase in passenger traffic could not be efficiently accommodated, rolling stock was aging and available coaching stock was always given to the miltary as a priority. Public criticism grew. [1: p553]

Closer cooperation between the railway and Sudan Railways and the marine services on Lake Victoria became essential, as did better connections with the Tanganyika rail system. The General Manager (Brig.-General Sir Godfrey Rhodes was seconded to the Army in October 1941. He was transferred to Iran and as a result he finally resigned his post as General Manager in June 1942, after being absent for some 8 months. [1: p553]

His replacement was not appointed, even on a temporary basis, until May 1942. 1942 saw a further increase in goods traffic and passenger numbers. Although military goods traffic fell slightly to 667,000 tons, “the total goods traffic increased to 1,808,624 tons and the passenger journeys by 42 per cent, to 2,333,033. The goods traffic would have been greater still if the short rains had not failed int eh later part of teh year, a misfortune which was partly responsible for the food shortage of 1943.” [1: p555]

Great difficulties were experienced in sourcing spare parts for the railway which were normally imported. The workshops had to rely much more on their own resources. Many engines had missed their intermediate 60,000 mile repairs and repair intervals were extended to 120,000 miles. Despite this the railways we able to meet the increases in engine mileage from 4,071,238 miles in 1939 to 5,546,577 in 1944. The workshops performed admirably, especially as they were still being called on to meet military needs as well as those of the railway. [1: p556]

During 1942, the railway placed a substantial order for new engines and rolling stock. In order to finance the deal, £500,000 was temporarily transferred from the Renewals Fund to the Betterment Fund. Half of which was covered by an allocation from the 1942 surplus. At the end of the year, the railway was left with a surplus of £893,620, (of which £447,626b was paid to the Betterment Fund; £250,000 was repaid to the Renewals Fund; £26,369 to the Superannuation Fund; and £69,625 to the General Reserve). [1: p557]

Despite significant increases in income, the massive increase in traffic resulted in a rapid deterioration in the general condition of the railway infrastructure and rolling stock. All non-urgent work was deferred.

“By the end of 1944 the railway’s Capital Account amouted to £24,255,938, of which sum £14,139,229 was interest-bearing capital and £10,116,709 was free of interest,” coming from Parliamentary Grants and the railway’s own revenue streams. [1: p559]

in 1943, military traffic increased to 889,000 tons. Rainfall was was short of expectations, navigational difficulties began to be experience on the Great Lakes and a plague of locusts and famine once again threatened. Exports decreased in imports rose. The total goods traffic on the railway increased to 2,024,238 tons. Passenger journeys rose to 2,745,229. [1: p560]

In December 1943, the workshops had to build 250 covered wagons and 130 high-sided open wagons which had been delivered as parts from the USA.

There was another large surplus at the end of 1943, (of this, £270,743 went to the Betterment Fund; £250,000 was used to wipe out the loan from the Renewals Fund; £29,500 went to a Gratuity Reserve Account; £100,000 to the Rates Stabilisation and Relief Account; £11,1430 to the Wartime Contingency Fund, and £152,831 was carried forward.

1944 brought no respite to the railway. Military traffic fell to 688,000 tons but the total goods carried rose to 2,084,594 tons. Passenger journeys rose to 2,752,647.[1: p561]

Seven new Barratt engines arrived – the ‘EC4’ class, as shown below, “although they were far less satisfactory than the engines of the ‘EC3’ class. The design of the new engines was imposed by the exigencies of war, and they gave a lot of trouble with hot axles and other defects. Due to unsatisfactory design, they required an intermediate overhaul sooner than was expected, and so they gave less assistance in hauling the heavy traffic than had been estimated.” [1: p562]

The official works photograph of a EC4 Class Garratt. [5]

“Although the machine shop was run night and day it could not produce enough finished parts to cope with the needs of incoming locomotives, which had generally run a greater mileage than was considered permissible before the war, in many cases without intermediate repair.” [1: p562]

Locomotives ran an average of 41,835 miles per engine. Very high mileages for Metre-gauge locos!

Both staff and stock were over the limits of their capacity/endurance. [1: p563]

“On paper the railway again earned a large surplus of £821,027; after adding the balance brought forward from 1943, £624,613 was allocated to the Betterment Funds, £267,245 to the Rates Stabilisaton and Relief Fund, £29,500 to the Reserve for Gratuities, and £52,500 to a Passages Equilibrium Reserve which was created to meet the heavy expenditure on passages for staff travelling on overseas leave, which was to be expected after the war.” [1: p563]

As is clear from these notes, the financial position of the railway was essentially no where near as good as the above figures suggest. The railway was rundown but because of the war it did not have the personnel resources to make use of surpluses in maintaining the railway. It was living off its capital! “The introduction of large engines and heavy and long trains … made it imperative to replace the present type of coupling and to effect improvements and alterations in the braking system if the standard of safety [was] to be maintained.”[1: p563]

The large surpluses of the war years would not be sustained indefinitely. Further problems would need to be addressed so as to secure the future of the rail network. Hill points out that providing an adequate water supply and an adequate fuel supply was paramount. “The shortage of water [had] resulted in damage to and repeated failures of locomotive. …. Progressive steps [needed to] be taken to re[place wood as a lcomotive fuel. Apart from the fact that it [was] a comparatively inefficient for the production of motive power in a steam locomotive, there [was] always the ever-present risk of causing fires on land adjoining the railway, with consequent economic loss to the country.” [1: p564]

1945 was the fiftieth anniversary of the railway. “Bay 11th December 1945, the achievements of the railway had far surpassed the most optimistic dreams of its creators. By that time, also, the demands made upon it were creating a situation which grew the more difficult as the moths slid by.” [1: p564]

Strenuous arguments were made back in the UK in favour of radical action to increase the number of engines, rolling-stock, general equipment and staff. The entreaties fell on deaf ears and only two light Garratt engines were procured during the year. These were Class EC5 locomotives as shown below. The railway demanded 443,00 engine miles per month, the workshops had such a backlog of work that a reduced mileage had to be agreed. A guarantee of 390,000 miles per month was negotiated. In the end, through all manner of means, an average locomotive mileage of over 465,000 per month was sustained throughout 1945. [1: p564]

EC5 Garratt locomotive. ” of these were supplied to the network after WW2. [4]

The rolling-stock position was greatly hampered by the failure of wheel sets obtained in the USA – by the end of the year 160 bogie wagons were out of service. [1: 564]

Passenger traffic increased once again to 2,838,250 journeys. Freight traffic dropped as a result of a significant decrease in military traffic after the end of the war. However, there was a marked decrease in the goods carried which attracted significant subsidies. The result was a record revenue form goods traffic of £3,106,671. [1: p364-365]

“Despite attempts to tap new sources of supply, a shortage of water again proved a serious handicap. The rainfall was generally below average, and the lack of water caused grave anxiety in many directions besides the railway. In Nairobi the situation was critical, and it was patent that drastic measures to increase the supply were essential.” [1: p365]

Labour difficulties in Uganda adversely affected the running of all trains into the protectorate. Those difficulties and some lesser issues in Kenya led to a significant re-evaluation of wages and war bonuses. [1: p365] The administration of the rialway also needed to enhance productivity and sought ways to incentivise increased output. [1: p566-567]

Towards the end of 1945, it was agreed that the 1921 loan should be redeemed at the earliest opportunity. In December 1945, the complete amalgamation of the Kenya and Uganda Railway and Harbours with the Tanganyika Railway and Ports Services was proposed. [1: p567] Political expediency placed this proposal on hold. [1: p568]

From a financial perspective the railway did far better in 1946 “than had been expected, for earnings were £896,750 above the estimate. … The surplus amounted to £745,992 compared with an estimated deficit of £59,522. In 1947, there was much the same story to tell. The railborne tonnage incrased by 6.08 percent. over 1946, and the ton-mile figure for March was the highest ever achieved. The earnings were more than £1,000,000 above the estimate and the surplus amounted to £888,214. [1: 569]

“The shortage of materials of all kinds, especially wagon tyres, exacerbated the problems of coping with the increased traffic, and a series of coal crises made matters worse. … The difficulties of ensuring an adequate coal supply impelled a decision to change over from coal to oil, which would also cause a reduction in the fuel bill.” [1: p570]

During 1947, “32 third-class bogie coaches [arrived] and enabled an end of the practice, enforced by the war, of carrying some third-class passengers in goods vehicles. A Diesel rail-car service was introduced on the Kisumu-Butere branch in August, and proved very popular with the local population.” [1: p570] Two examples of these Wickham rail-cars are shown below.

Metre gauge 200hp Wickham Rail Car No. 3, one of the three 58 seater railcars built for the Kenya & Uganda Railways Kisumu-Butere branch line. Works Nos. 2828-2830 ordered in January 1939 and finally delivered in May 1946. Fitted with Saurer BXDL engines. (Public Domain [2]

Metre gauge 200hp Wickham Rail Car No. 2, numbered 2829 and delivered after WW2. (Public Domain) [3]

“Work on the Nairobi-Nakuru realignment, which had been held up during the war … was resumed” and eventually completed. [1: p570]

And over the period to the 1st May 1948, negotiations were undertaken to amalgamate the two railway systems in East Africa. This negotiations concluded on 1st May 1948 and Hill’s story of the old Uganda Railway ends at that point. He was, after all writing in 1949. We need to look elsewhere for the ongoing story of the railway network in East Africa from 1948 on through the gaining of independence by Kenya, Tanganyika and Uganda up to the present day.

References

- M.F. Hill; Permanent Way – The Story of the Kenya and Uganda Railway – Volume 1; Hazel, Watson & Viney Ltd, Aylesbury & London, 1949.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/29903115@N06/41904741772, accessed on 29th March 2021.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/29903115@N06/42611529222/in/dateposted, accessed on 29th March 2021.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kenya_Uganda_Railway_class_EC5.jpg, accessed on 21st March 2021.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2018/06/19/uganda-railways-part-24-locomotives-and-rolling-stock-part-b-1927-to-19 and https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/KUR_EC4_class, accessed on 19th June 2018.