The September 1950 edition of “The Railway Magazine” includes a short article on the Ashover Light Railway in the Peak District to the south of Chesterfield. In the spring of that year, the railway was finally closed to traffic.

The featured image above comes from the front page of the Ashover Light Railway Society’s website. That Society is working to recreate the atmosphere of the Ashover Butts terminus of this railway in its heyday. [3] The website can be found at: http://www.alrs.org.uk

The featured image in this blog was painted by Eric Leslie. You can find out more about him, and his art, on the FB page drawnbysteam. He donates his work free of charge to several NG railways, helping them to raise funds.

NB: I always seek to ensure that no copyright is infringed in my blogs. Any infringement is unintentional. I will immediately take down any image when asked to do so by that image’s copyright owner.

The article states: “Although one of the most recently built light railways in Great Britain, the Ashover Light Railway, which was closed to all traffic on 31st March last (1950), had its roots in the very earliest days of British railway enterprise, for its owner, the Clay Cross Co. Ltd., was founded in 1837 by George Stephenson himself. The Clay Cross undertaking was, in effect, a by-product of railway construction, for it was while George Stephenson was superintending the building of a tunnel at Clay Cross for the North Midland Railway that he saw the vast mineral wealth revealed by the excavations of the workmen, and conceived the idea of forming a company to exploit these valuable natural resources.” [2]

The Clay Cross Company was formed by George and Robert Stephenson and the board included a number of railway worthies. Among them were George Hudson, S. Morton Peto and William Claxton. For a time, the Clay Cross Company was the largest independent employer in the UK. [1]

The Ashover Light Railway was a 1′ 11.5″ (597 mm) narrow gauge railway in the Peak District in the UK. It connected Clay Cross and Ashover. It was built to transport minerals such as limestone, fluorite, barytes and gritstone to the works at Clay Cross and further afield. [1] Its primary function related to minerals which are used in steel manufacture and which, ultimately, were exported to the USA and Canada. It was “primarily an adjunct to the undertaking of the Clay Cross Company, it also carried public traffic.” [2]

In 1918, the Clay Cross Company expanded its interests by purchasing the Overton Estate at Fallgate with the aim of extracting minerals. This required the development of a means of transportation for the minerals mentioned above. [1] Loads were anticipated to be relatively light and Light Railway Orders were used to gain permission for the construction of a narrow gauge line, “which coupled with the facts that, for much of its course, it was built on land belonging to the Clay Cross Company and that no very heavy engineering works were involved, kept construction costs low.” [2]

The first Light Railway Order was granted on 4th December 1919, which incorporated the Ashover Light Railway Company. Subsequent powers were contained in Orders of 1920, [1] 1922 and 1924. [2][3] “The Order was passed … on condition that the railway provided a passenger service. This was agreed and construction of the Ashover Light Railway began.” [3]

In 1920 H. F. Stephens, the consulting engineer for the line, had proposed building the entire railway to 2 ft gauge. Prior thinking had been to establish a standard-gauge rope worked line. Stephens proposal considerably reduced the costs of construction and the plan was approved. [1] Construction started in 1922.

“As the construction of the line progressed, it was realised that a passenger station at Hollow Lane would be a little tight for space, and therefore in May 1924, another Light Railway Order was applied for. This was for yet another extension, this time going from Hollow Lane to Ashover Butts where there was more room to build a station. The Order went through in August that year.” [3] The railway opened to goods traffic in 1924. The formal opening to passenger traffic took place in 1925. The line was built using surplus equipment from the War Department Light Railways. [3] The Wilipedia article about thw line states: “The line was laid throughout with 30-lb. flat-bottom rails on timber sleepers. Traffic control was by Wise’s patent train staff, and there were no semaphore signals. Telephone boxes were provided along the route to enable train movements to be reported to headquarters and controlled if necessary.” [2]

Ashover was already a tourist attraction and the route of the railway up the Amber valley was itself beautiful. The line opened from the Clay Cross works to Ashover on Monday 6th April 1925. Public traffic began on 7th April and the line was immediately popular. [2]

“The inaugural service consisted of five trains daily from Clay Cross to Ashover, a sixth starting from Hill Top loop but not picking up passengers until Holmgate, and extra late trains on Wednesday (one) and Saturday (two) nights. There were eight trains daily from Ashover to Clay Cross, and a ninth from Ashover to Holmgate. Five passenger trains each way were run on Sundays. Cheap tickets available for 12 single journeys were issued to workmen, and day returns for the general public on Wednesdays, Saturdays, and Sundays. Fares were low; cheap day returns being issued for 6d, — Clay Cross to Ashover, and it is not surprising that the trains were well patronised. Five thousand passengers were carried in the opening week, which included the Easter holiday.” [2] Except for Chesterfield Road, Stretton, Woolley and Fallgate, trains called at the other halts only when requested. [2]

“At holiday times such as Easter and Whitsun, the Clay Cross Company laid on special outings for its employees. These involved a trip to Ashover where the day was spent picnicking on the banks of the River Amber. The popularity of the line encouraged General Jackson to provide more facilities at Ashover Butts, resulting in the construction of the ˜Where the Rainbow Ends” cafe.” Holidays were busy and extra carriages often had to be found to cope with demand. [3]

The passenger service continued to prove successful in the 1920s, but competition from buses saw numbers decline and Winter services ceased in the early 1930s. Ultimately, all passenger services were withdrawn by 1936. [3] For the last years of the life of the passenger service, the Summer timetable saw only one formal intermediate stop, at Stretton. Other stops were by request. Passenger trains ran only on Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays, with a frequency reduced to six trains each way on Wednesdays and Saturdays and three on Sundays, The time taken on the journey varied from 45 to 55 minutes. The regular passenger service was finally withdrawn in September, 1936. [2]

From that time, only occasional passenger trips were made. The railway continued to be used for mineral traffic, until 31st March 1950 when the line was finally closed. An Order for the winding up of the Company was issued by the Ministry of Transport on 20th May 1950. [2]

The goods service sustained the railway for its remaining years. Although at a much reduced scale that in the early years of the line. [3]

Most of this traffic came “from the Clay Cross Company’s own quarries at Ashover, Fallgate and Milltown. The extracted minerals were then used in the Clay Cross Works, or sold off around the country. Coal for the surrounding villages was carried on the railway in the early days, but this died down as the roads improved. In fact, the railway’s success led to cheaper and quicker competition from road transport.” [3]

“On September 9, 1946, General Jackson died aged 77. His son, Humphrey (Hummy), took control of the Clay Cross Company, but could not change the declining fortunes of the railway. The following year, Harold Skinner, who was a long standing driver on the railway, resigned, leaving only Charlie Maycock as sole employee of the Ashover Light Railway. By the end of 1947 the railway had made a loss of £2,000 and the Clay Cross Company made it known that they intended to close the line.” [3]

“In 1949 the railway’s last remaining contract with Butts quarry was terminated and the quarry closed in 1950.” [3] The railway closed on 31 March 1950. Most of the rail remained in place through October of that year when a last inspection trip was made. After that the majority of the railway was lifted. “The scrap dealers, Marple & Gillott, moved in that same day and commenced the lifting of the track. In September 1951 the Pirelli Bridge over Chesterfield Road was removed, marking the final stage in the dismantling of the railway. However, a short section of railway was retained at Fallgate as fluorspar was still being excavated there. This continued until early 1969 when the wagons and track work were scrapped in favour of road transport.” [3][1]

Locomotives and Rolling Stock

BRIDGET was built by Baldwin in 1917. [3]

BRIDGET was built by Baldwin in 1917. [3]

PEGGY, also built by Baldwin in 1917. PEGGY was scrapped in June

1951. [3]

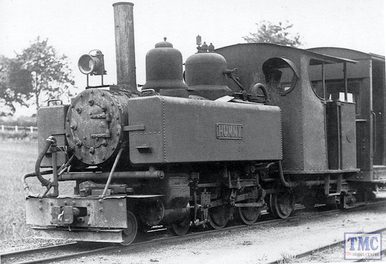

“Almost all of the equipment provided for the building and running of the railway was acquired second-hand from the War Stores Disposals Board. Four American-built, Baldwin 4-6-0 tank locomotives arrived and were named PEGGY, HUMMY, JOAN, and GUY; the names given to General Jackson’s children. Shortly afterwards, a fifth similar locomotive was purchased and was given the name BRIDGET.” [3] The locomotive stock was latter augmented by a further example of the class which was name GEORGIE.

As we have noted, these locos were built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works, Philadelphia, U.S.A., “for use on light railways on the French and other fronts during the war of 1914-1918. The locomotives were of typically American appearance, having sand domes, an American type of chimney, and central buffers, with outside cylinders (9 in. by 12 in.), Walschaerts valve motion, and coupled wheels measuring 1 ft. 11.5 in. dia. They had vacuum brake equipment for working passenger trains. At first they were painted Midland red to match the coaches, but this was later changed to black. By 1939, some of these steam locomotives had finished their useful life, and Guy and Georgie were scrapped.” [2]

Two further powered purchases were made. The Railway Magazine article states: “A small 0-4-0 diesel locomotive was secured, and a petrol tractor constructed with Muir-Hill Fordson equipment. There was also a small petrol-electric tractor named Amos used at Fallgate gravel pits which was illustrated and briefly described in our July-August, 1944, issue, when it was stated that this appeared to have been put together in 1939 largely from the remains of an ex-W.D. gauge locomotive. Joan appears to have been scrapped about 1944, but, with the remaining three, there is some uncertainty as to what may be regarded as ‘scrapped’ or ‘under repair’.” [2] Joan, pictured in 1926, appears to be in charge of one of the bogie coaches. [4]

Joan, pictured in 1926, appears to be in charge of one of the bogie coaches. [4] Joan at Stretton Level Crossing with what looks like a railway society tour in open mineral wagons. The coping stone to the right of the picture is still in place at the crossing location. [5]

Joan at Stretton Level Crossing with what looks like a railway society tour in open mineral wagons. The coping stone to the right of the picture is still in place at the crossing location. [5]

The Railway Magazine article also states: “Four passenger coaches were provided when the line opened. The Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Co. Ltd. constructed the underframes and bodies, but acquired the bogies from surplus war material. They were of the open, tramway type, and fares were collected on the trains. Later, some open-sided bogie coaches were acquired for use in summer, when passenger demands were extra heavy. The saloons were divided into two compartments, and electrically lighted. They were painted a dark red, lettered in gold, and were quite attractive looking vehicles. Riding was fairly steady, but somewhat noisy, due, probably, to the very small wheels, together with the light rails.” [2]  An Ashover Light Railway passenger train. [9]

An Ashover Light Railway passenger train. [9]

As the general condition of the railway deteriorated, only 4 of the original 12 passenger coaches were kept in running order. These were the four large bogie carriages supplied by The Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Co. Ltd. They “all ended up as stands on the Works bowling green. One was scrapped in 1960, two were moved to the Lincolnshire Coast Light Railway, [8] and are numbered Nos 1 and 2. No 4 was moved to the Golden Valley Light Railway. By default, … carriage No 3 was the one that was scrapped in 1960. [3] No. 2 at the Lincolnshire Coast Light Railway having been recently restored, © Nick Holliday (RMWeb) [10]

No. 2 at the Lincolnshire Coast Light Railway having been recently restored, © Nick Holliday (RMWeb) [10]

More recently, No. 4 has been resting at the Midland Railway Centre at Butterley. It is now in a fully restored condition.  Ashover Light Railway Coach No. 4. [6]

Ashover Light Railway Coach No. 4. [6]

Mineral traffic was conveyed in open bogie wagons purchased from war surplus stocks, in the years immediately prior to closure a stock of 59 wagons was maintained. [2]

The two images immediately above show examples of these open bogie wagons at Fallgate quarry. [7]

The two images immediately above show examples of these open bogie wagons at Fallgate quarry. [7]

Part 2 of the story will follow the route of this line from Clay Cross/Egstow to Ashover.

References

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashover_Light_Railway, accessed on 13th January 2018.

- The Ashover Light Railway; The Railway Magazine, Volume 96, No. 593, September 1950.

- http://www.alrs.org.uk/site/?page_id=31, accessed on 14th January 2019.

- https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/374221050282985511, accessed on 14th January 2019.

- http://colonelstephenssociety.co.uk/the%20colonels%20railways/ashover%20light%20railway/ashover%20light%20railway%20members%20weekend/ashover%20light%20railway%20members%20weekend%20route.html, accessed on 14th January 2019. … RLinkinS on the forum national-preservation.com says: “I think this is the Birmingham Locomotive Club’s trip on 24/08/1948. There is a colour picture in Michael Whitehouse’s new album and the stains on the front of the smokebox are identical.” (https://www.national-preservation.com/threads/the-ashover-light-railway.1302307/#post-2352339, accessed on 16th January 2019).

- http://museumofthinobjects.com/2014/08/23/derbyshire-dales-tales-4-midland-railway-centre-butterley, accessed on 15th January 2019.

- http://colonelstephenssociety.co.uk/the%20colonels%20railways/ashover%20light%20railway/ashover%20light%20railway%20photo%20gallery.html, accessed on 15th January 2019.

- http://www.lclr.co.uk, accessed on 15th January 2019.

- https://www.deviantart.com/ffdp-neko/journal/Remembering-the-Ashover-light-railway-565004075, accessed on 16th January 2019.

- http://www.rmweb.co.uk/community/index.php?/topic/115061-hollidays-lincolnshire-holiday-modelling-inspirations-hopefully/page-2, accessed on 16th January 2019.

- https://www.themodelcentre.com/391-028, accessed on 18th January 2019.

Nice blog Roger, thanks for sharing. Regards, Matt from WNXX

I remember Fallgate quarry with the long wagons from the early 1960s. My grandfather used to park there when teaching me fly-fishing on the river Amber, between Fallgate and Ashover.

I grew up in the old wharf-house (for Pentrich Colliery) on the Cromford Canal at Lower Hartshay, near Ripley in Derbyshire. The house has now been demolished and an incongruous large modern house built to replace it.

There were many of the square stone blocks with the drilled hole for the rail spike still around, from the earlier days of a plateway, coming down from two small collieries between Pentrich and Oakerthorpe. Sadly my father used a chisel and lump hammer to cut these in two, for making the edging for the garden. (It horrifies me now!)

Until the A38 extension, from Derby to J28 on the M1 was built, in the mid 1970s, the area around the old Butterley Company site contained a great deal of industrial archaeology sites. Early blast-furnaces, plateway and early railway remains, canal and reservoir infrastructure were all within a few hundred yards.

Nearly all demolished in the 1970s drive to pave everything over.

One of my first railway photographic expeditions was to Ashover and Fallgate, just before the remaining stock was scrapped.