An old copy of Hornby Magazine fell open at a modelling idea – the creation of a model representing the Ballachulish line in Western Scotland. Having walked a length of this line in the past, the article grabbed my attention and prompted some research. [1]

Ballachulish Railway Station.[4]

Ballachulish Railway Station.[4]

Ballachulish is a village at the foot of Glencoe in the Scottish Highlands. Glencoe is a deep valley which forms the natural road route into this remote part of Scotland. During the Victorian era it’s transport links centred around a steamer connection with Fort William, about 15 miles North, and Oban, a little further in a southerly direction.

Despite its remote location, Ballachulish had extensive slate quarries and during the 1880s it was hoped that local interest would be served by a railway line from Crianlarich up Glencoe and on to Fort William. This was not to be. The Rannoch Moor route was chosen instead. Other lines, such as an Oban to Fort William Railway failed to materialise.

Instead, rather late in the day in 1896, a branch line was authorised from the Oban-Crainlarich line at Connel Ferry. It was hoped that this would meet a similar line from Fort William but, although powers were obtained, it was never built because of problems gaining permission for bridges across sea lochs. [1]

Instead, rather late in the day in 1896, a branch line was authorised from the Oban-Crainlarich line at Connel Ferry. It was hoped that this would meet a similar line from Fort William but, although powers were obtained, it was never built because of problems gaining permission for bridges across sea lochs. [1]

Ballachulish

Ballachulish is a slightly confusing place. It’s not unusual to find places that come in two halves. But Ballachulish comes in two halves plus another, larger, settlement two miles along the road towards Glencoe.

The name comes from the Gaelic for village of the narrows, and the first settlement to bear the name lay where North Ballachulish is today. Its twin, on the south side of the loch, rapidly followed. Loch Leven narrows dramatically here and North and South Ballachulish grew up around the slipways used by ferries crossing the loch from a very early date. A vehicle ferry started to cross the narrows in 1912, but the service finally disappeared in 1975 when the bridge opened. With it disappeared the choice facing drivers of the sometimes long ferry queues at busy periods or the nineteen mile detour via Kinlochleven.

While the ferry has long gone, the slipways that served the ferry remain: though they are by no means opposite one another. The steel truss bridge that opened here in 1975 fits nicely into its environment. Indeed, it comes as something of a surprise to find it is such a relatively recent addition to this part of the Western Highlands.

South Ballachulish largely comprises the slipway and the nearby Ballachulish Hotel. Close to the steps leading down from the bridge to the Oban road near the hotel is a memorial to James Stewart, hanged here in 1752 for the Appin Murder. This was the killing of Colin Campbell, an event used as the basis for Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel Kidnapped. Stewart’s execution was a result of the greatest miscarriage of justice in Scottish legal history. A number of the sites associated with the Appin Murder have been linked by the Last Clansman Trail.[2]

Ballachulish Bridge should not be confused with the Connel Ferry bridge closer to Oban.

North Ballachulish is a little more developed and is home to an art gallery, lochside hotel and the slipway for the old ferry.

The largest settlement carrying the name of Ballachulish lies on the south side of Loch Leven, a mile or so west of the village of Glencoe. This started life as the hamlets of East and West Laroch in the 1500s, names still attaching to parts of the village on detailed Ordnance Survey maps. In 1693, slate was first quarried here in the Ballachulish Slate Quarries (only a year after the Glencoe massacre took place nearby). By the early 1700s, this had developed into a major slate quarrying operation which continued for over 250 years until 1955, when the quarries closed. The name of Ballachulish simply seems to have attached itself to the larger village that grew out of the earlier settlements to house the 300 workers and their families.

The Ballachulish Medical Practice today stands on the site of the railway station that formed the terminus of a branch line railway running from Connel via Ballachulish Ferry. This opened in 1903 and closed in 1966. Ballachulish now has its own Visitor Centre, which comes complete with ample parking and public conveniences. Just across the road from the visitor centre are the old Ballachulish slate quarries, which now provide scenic walks. There’s no mistaking what they are, but in the half century since they closed, nature has made a start on the task of reclaiming what was once taken from it. The main settlement of Ballachulish is now largely bypassed by the A82, which passes along the Loch Leven side of the village. [2]

The Railway

Construction work on the line started in 1898 and was completed in 1903. This was one of the last branch lines to be built in the UK. [1] The following notes in italics are taken from an on-line article published on the website “Unseen Steam” on the 50th Anniversary of the closure of the line in March 2016. [5] Images used are credited where possible and taken from a variety of sources.

The authorised capital of the new line was £210,000, of which the Caledonian Railway agreed to fund £15,000. There were two major engineering structures required: the viaducts over Loch Etive and Loch Creran at Creagan. The former, constructed by the Arrol Bridge & Roofing Co, was started in 1898. The cantilever bridge that resulted was the second only in length to the Forth Bridge and was the longest steel single-span bridge in Britain. Construction Drawing – Connel Bridge. [8]

Construction Drawing – Connel Bridge. [8]

Connel Bridge under construction. [4]

Connel Bridge under construction. [4]  Connel Bridge under construction. [4]

Connel Bridge under construction. [4] Connel Bridge. [7]

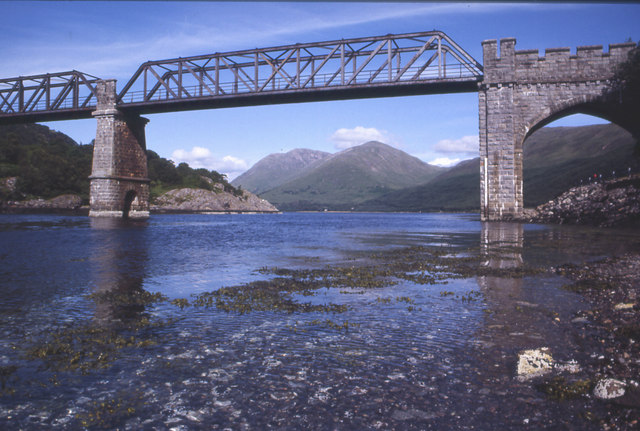

Connel Bridge. [7] Creagan Railway Bridge, Loch Creran. [6]

Creagan Railway Bridge, Loch Creran. [6]

The Connel Ferry Bridge, the world’s 2nd largest steel cantilever bridge, Argyllshire, Scotland, opened in 1903. [9]

The 27½-mile long branch opened throughout to passenger services on 28 March 1903. There were intermediate stations at North Connel, Benderloch, Creagan, Appin, Duror, Kentallan and Ballachulish Ferry that opened with the line. Barcaldine Siding (Halt from 1960) followed in 1914; this station was closed during World War 2 and was used for summer services only for a period after reopening postwar. Ballachulish Ferry was to be closed between 1 January 1917 and 1 March 1919 as an economy measure during World War 1. The population of Ballachulish when the line opened was less than 2,000 but quarried stone represented a useful source of freight traffic.

During the summer of 1910 there were three return workings over the branch each day, making a connection with the ferry to and from Kinlochleven. Services ran to and from Oban, with reversal at Connel Ferry. Down services departed from Oban at 8.20am, 11am, 5pm (Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays only) and 8.30pm (Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays only; this was the only working that did not connect with the Kinlochleven ferry). Up workings departed at 7.15am, 11.15am and 3.45pm. A single journey from Connel Ferry to Ballachulish took about 70 minutes. There was no service on Sundays.

By the summer of 1947, the final year of the line’s operation by the LMS before Nationalisation in January 1948, there were still only three return workings per weekdays. Departures from Oban were at 8.10am, 12.5pm, 4.pm (except Saturdays) and 8.50pm (Saturdays only). Services departed from Ballachulish at 7.30am, 10.50am, 3.50pm (Saturdays only) and 4pm (except Saturdays). There was no Sunday service. A revised pattern of service was operated by British Railways (Scottish Region) during the period from September 1964 through to June 1965. There were two down departures from Oban, departing at 8.15am and 5pm with a third service starting at Connel Ferry at 12.30pm. The station at North Connel was a request halt for both the 8.15am and 12.30pm services. In the up direction there were departures from Ballachulish at 7.14am (to Oban), 10.40am (to Connel Ferry), 4.20pm (to Oban) and a Saturdays only 6.57pm (to Oban). For all, apart from the 7.14am, the station at North Connel was a request halt.

In terms of motive power over the line, the early years witnessed the operation of three generation of 4-4-0s specifically designed for the C&OR — the ‘Oban bogies’. During the war Class 5 4-6-0s are known to have operated troop trains to Benderloch. In the later years, steam passenger services were dominated by Macintosh-designed ‘19’ class 0-4-4Ts. By the end of 1961, three of the class were based at Oban — Nos 55204/217/260 — but before the final demise of steam over the branch, these were replaced by ex-LMS or BR 2-6-0s. With the dieselisation of the C&OR main line and its branches to Killin and Ballachulish, 45 steam locomotives were replaced by 23 Type 2 diesel-electrics plus four diesel shunters. It was the diesel-electrics that operated the final passenger services over the line to Ballachulish.

Whilst both the Crianlarich-Oban and Crianlarich-Fort William-Mallaig lines were not listed for closure under the Beeching Report of March 1963 — albeit a number of intermediate stations on the former were — the line to Ballachulish was not so fortunate. Passenger traffic ceased over the on 28 March 1966; with freight having ceased in June the previous year, the line was closed completely from that date.

Today many of the structures that once served the line are still extant or have been reused for new purposes. The station at Ballachulish remains, having been converted into a medical centre. Platforms remain extant at Ballachulish Ferry with a section of the line westward having been converted by Sustrans into a cycleway. At Kentallen, the platforms of the station have been incorporated into a new hotel. At Duror, the station has been converted into a private house. The station at Creagan, which was overgrown for many years, has now been restored. The piers of the bridge across Loch Creran at Creagan remain, having been used in the late 1990s for a new bridge for the A828. The bridge at Connel Ferry also survives; following the closure of the line it was converted to take road traffic exclusively. [5]

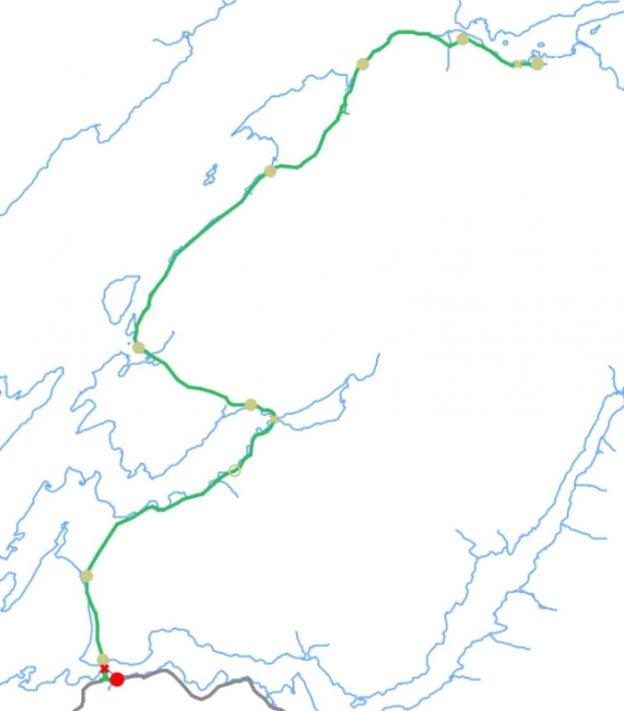

The Route of the Ballachuliush Branch. [3]

The Route of the Ballachuliush Branch. [3]

The Connel Bridge

The red ‘x’ on the plan above marks the Connel Bridge which sits just to the north of the Calendar to Oban line. The bridge was the largest cantilever span in Great Britain aside from the Forth Bridge when completed. A truly unique bridge, it features several members positioned in unusual angles and inclines, resulting in a striking appearance that looks ahead of its time and may even call to mind images of modern cable-stayed and steel rigid-frame bridges.

The bridge was originally built as a single-track railway bridge to carry the Callander and Oban Railway. In 1909, a special railway service was added that carried motor vehicles across the bridge, albeit only one car at a time. This unusual arrangement did not last long, however. By 1914, the bridge was reconfigured with a roadway along the western side of the deck and the railway on the east side of the deck. Despite this arrangement, the relatively narrow width of the bridge prevented cars and trains from crossing the bridge at the same time. When a train needed to cross the bridge, the crossing was treated like a grade crossing, with gates to keep cars off the bridge. In 1966, the railway line was closed and bridge was reconfigured as a highway-only bridge, with the rails being removed. The narrow bridge operates as a one-lane bridge, with traffic signals controlling the flow of traffic over the bridge. [8]

The distinctive design of the cantilever truss is due to the configuration of the trusses over the piers. Typically, cantilever trusses have a vertical post, sometimes called the “main post,” located directly over the pier that is also at the deepest section of the truss web. For the Connel Bridge, these posts are instead inclined, not only inward toward the center of the span, but also inward toward the centre of the roadway. As such, the inclined main posts extend out beyond the truss lines to the pier below, giving the bridge a bowed out appearance when viewed from certain angles. The inclined posts also mean that the deepest “tower” section of the truss is located not over the pier, but partway into the central span of the truss. [8]

The inclined main post is countered by what engineering periodicals described as a “back strut” extending from the bearing on the piers back to the abutment at the roadway level. The back struts angle out to meet the main post locations outside of the truss lines, adding to the bowed out appearance of the bridge. The end post of the truss, also inclined, extends all the way to the main post of the truss, meaning there is no upper chord for this entire length, an unusual design that gives the bridge a striking appearance when approached on the road. If the end post, the main post, and the back strut at each end of the bridge are looked at as a single shape, the bridge has the appearance of two giant triangles resting on their apex at the piers. Another unusual detail of the truss is found at the deck level, where a beam that may look like a lower chord of the truss to casual viewers also angles out to meet the inclined main post at the roadway level, and was described as an “outer boom” in engineering periodicals. [8]

This bridge used steel from a large variety of companies and mills. Numerous names can be found on the steel and are documented in the enormous detail in the photo gallery available for this bridge.[8]

The bridge crosses the Falls of Lora, turbulent rapids that are strongly affected by tidal flows. This is one of the reasons a cantilever truss bridge was constructed at this location. it could be erected over the waterway without the use of falsework in the fast-flowing rapids.

The Transactions of the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland, 1903 had an obituary for Thomas Arthur Arrol the builder of this bridge. Thomas Arthur Arrol should not be confused with the more famous Sir William Arrol, who also built bridges.

Thomas Arthur Arrol was born in Glasgow on the 24th August, 1852, and was educated at the Collegiate and High Schools of Glasgow, and at the Glasgow University. He served his time as an engineer with Messrs P. & W. MacLellan and remained in their service till he became general manager. After spending a few months in the United States he returned to his native city and entered into partnership with his brother, the late Mr James Cameron Arrol. Together they founded the Germiston Works, at which roof and bridge building and general engineering were carried on until 1892.

The concern was subsequently converted into a Limited Company under the designation of Arrol’s Bridge & Roof Co., Ltd., with Mr T. Arthur Arrol as managing director. Under his supervision many important contracts were successfully carried out, and among others in hand at the time of his death were those for the Connel Ferry Bridge, which is the second largest cantilever bridge in Europe; the Larkhall and Stonehouse viaducts for the Caledonian Railway; and the transporter bridge across the Mersey at Runcorn, which is the first of its kind in Britain. He died suddenly at Aberdeen on 29th October, 1902. Mr. Arrol joined the Institution as a Member in 1875, and took an active interest in its affairs. He was a Member of Council for Sessions 1882-84, and a Vice-President for Sessions 1884-86. He was again elected a Member of Council in April, 1901. [8] A striking overhead image from Google Earth showing the bridge and the Falls of Lora.

A striking overhead image from Google Earth showing the bridge and the Falls of Lora.

Immediately north of the bridge the railway entered the first railway station on the Branch. Road and rail first had to separate and the railway then entered North Connel railway station which was adjacent to Oban Airport.  A train approaches the bridge from the north. [10]

A train approaches the bridge from the north. [10] A train leaves the bridge and heads towards North Connel Station. [4]

A train leaves the bridge and heads towards North Connel Station. [4]

This video was sent tome in January 2020 by Chris Deuchar with permission to share it in this article. It shows both the area around Connel Bridge and a car journey over the bridge. [12]

Further North the line followed the line of what is now the A828. The original road north ius now an access road for Oban Airport.

Further North the line followed the line of what is now the A828. The original road north ius now an access road for Oban Airport.

The roads crossed the line just south of North Connel Station and dropped down to meet the roads on the north side of Loch Etive before passing under the line in a westerly direction. The road then turned sharply to the north and passed over the line on a bridge at South Ledaig.

The old road and the railway ran parallel to each other heading north through North Ledaig and on to the next station at Benderloch.

Approaching Benderloch the two ran immediately next to each other as can be seen on the adjacent OS Map.

Approaching Benderloch the two ran immediately next to each other as can be seen on the adjacent OS Map.

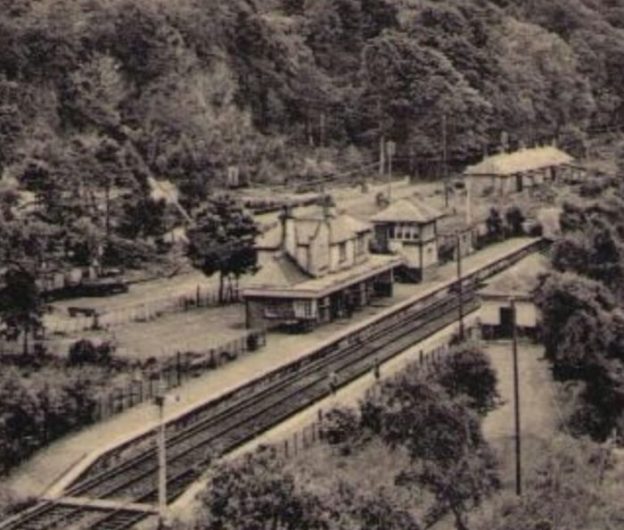

The station at Benderloch was laid out with two platforms, one on either side of a crossing loop. There were sidings on both sides of the line. There was a large two story station house in the style typical of the line, one of which still remains at Duror. There was also a standard design signal box.

The south bound track was the faster line with the north bound track forming the loop. Goods facilities/sidings were to the south of the station. The station was attractive and appears to have been cared for well.

The south bound track was the faster line with the north bound track forming the loop. Goods facilities/sidings were to the south of the station. The station was attractive and appears to have been cared for well. Benderloch Station. [11]

Benderloch Station. [11] Benderloch Station taken from a north bound train. [4]

Benderloch Station taken from a north bound train. [4] Benderloch Station taken from the south with a branch goods heading towards Connel Ferry. [4]

Benderloch Station taken from the south with a branch goods heading towards Connel Ferry. [4]

References

1. Evan Green-Hughes; Ballachulish; Hornby Magazine Issue 61, July 2012, p44-46

2. https://www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk/ballachulish/ballachulish/index.html, accessed on 1st January 2019.

3. https://www.railscot.co.uk/companies/B/Ballachulish_Branch_Callander_and_Oban_Railway, accessed on 1st January 2019.

4. http://oldappin.com/ballachulish-railway-line, accessed on 1st January 2019.

5. http://www.unseensteam.co.uk/News-spotlight/Ballachulish-closure, accessed on 1st January 2019.

6. https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1589044, accessed on 1st January 2019.

7. https://www.westcoasttours.co.uk/blog/2016/connel-bridge-and-the-falls-of-lora, accessed on 1st January 2019.

8. https://historicbridges.org/bridges/browser/?bridgebrowser=unitedkingdom/connelbridgeconnelbridge, accessed on 1st January 2019.

9. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Media-Storehouse-Poster-Connel-4331400/dp/B07BB5HMYH, accessed on 1st January 2019.

10. http://www.myrailwaystation.co.uk/FORMER%20LOCATIONS/pages/NORTH%20CONNEL%20STATION_%20With%20the%20station%20behind,%20the%20train%20crosses%20the%20road%20before%20moving%20on%20to%20the%20bridge_jpg.htm, accessed on 1st January 2019.

11. http://ardchattan.wikidot.com/benderloch-station, accessed on 1st January 2019.

12. https://vimeo.com/324830517, accessed on 15th January 2019.

Pingback: The Ballachulish Railway Line – Part 3 | Roger Farnworth

Excellent Article…many thanks

excellent article and films

I travelled on the last day of service and I have a book about the building of the railway regards Barrie P Spink

Years ago some people at work told me how they had travelled up to Ballachulish on the London sleeper when it was diverted because the line to Fort William was blocked by snow. I think they were dropped off at Ballachulish Ferry platform and picked up by buses on the North side of the loch but the buses could have been at Ballachulish station.

It is a beautiful route for walking, cycling and driving! Pity about the trains!

During a family holiday in the early 1960s we crossed the bridge. My father worked for British Rail as a boilermaker and was affronted to be asked to pay the toll charge. After an exchange, we were allowed to cross without paying.

It is still a wonderful experience going over!

Thanks for the memories.

A few years ago someone created a model railway display an imaginary Fort WIlliam extension of the Ballachulish line and it was featured in a model railway magazine.

There was a large set of sidings On the South side of Connel Bridge, these were built for the Admiralty in WWII – some claimed it was for the RAF but that seems unlikely.

Excellent webpage – many thanks!