Fox, Walker & Co. Ltd

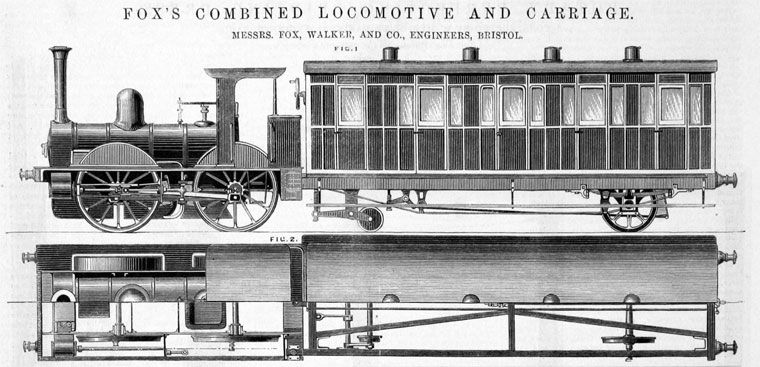

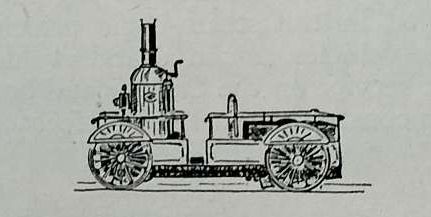

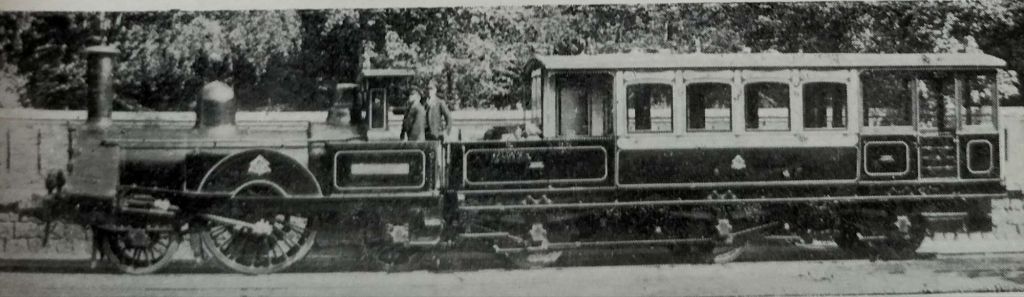

While looking for information about locomotives built by Fox, Walker &Co. for the Whitland & Taf Vale Railway, I came across the image below, which shows a ‘combined locomotive and carriage’.

Grace’s Guide provides no more information about this unit, but more can be found on the Model Engineering website in the form of a short article dated 19th February 1869 which appeared in the journal ‘Engineering’. [9]

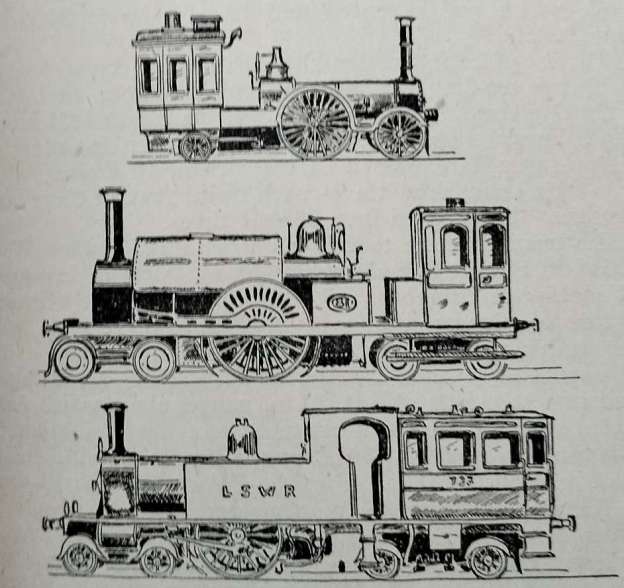

“We illustrate above an arrangement of combined locomotive and carriage designed and patented by Mr. Fox of the firm of Messrs. Fox, Walker, and Co., of Bristol. According to this plan a four-wheeled tank engine with a short wheel base is coupled by a strong draw-pin to a passenger carriage, this carriage having a single pair of wheels at the hind end only, the front end being supported by springs fixed on the engine frame, as shown in the plan. The carriage is, however, provided at the front end with a pair of wheels which can, by the arrangement of screw shown, be lowered down so as to bear upon the rail and support that end of the vehicle when it is desired to uncouple it from the engine. The engine shown in our illustration has four coupled wheels 5 ft. 6 in. in diameter, and outside cylinders 8 in. in diameter with 12 in. stroke; it has, moreover, a tank placed at the front end under the smokebox so as to approximately balance the weight placed on the hind end of the engine by the carriage. The total weight of the combined engine and carriage is estimated at 15 tons empty, and 24 tons with the engine in working order, and the carriage containing its full complement of passengers. The greatest weight on a pair of wheels is 9 tons. The engine is intended to draw two carriages, besides the one directly connected with it, and containing in all 150 passengers, at the rate of 40 miles an hour on a level, or its own carriage, carrying 50 passengers, up an incline of 1 in 50 at a speed of 15 miles per hour. To enable it to do this, however, it would be necessary either that the cylinder power should be increased, or that the boiler should be worked at a somewhat higher pressure than is adopted in ordinary locomotive practice. In describing Mr. Fox’s engine it is only fair that we should state that, before receiving his tracings we were shown by Mr. Fairlie the drawings of a combined engine and carriage which he had designed with the same object as led to the production of Mr. Fox’s plans, namely to effect a reduction in the dead weight and working expenses of railway trains, and to produce an arrangement suitable for carrying on a light traffic on a road abounding with sharp curves.” [9]

R.W. Kidner

Back in 1947, R.W. Kidner collaborated with the Oakwood Press to produce a series of monographs about road and rail transport. I had not been able to find a copy of the relevant part of Kidner’s work, [1] before completing the first six articles to which this article is an addendum. The first of those articles can be found here. [2]

This article includes relevant material from Kidner’s monograph. [1]

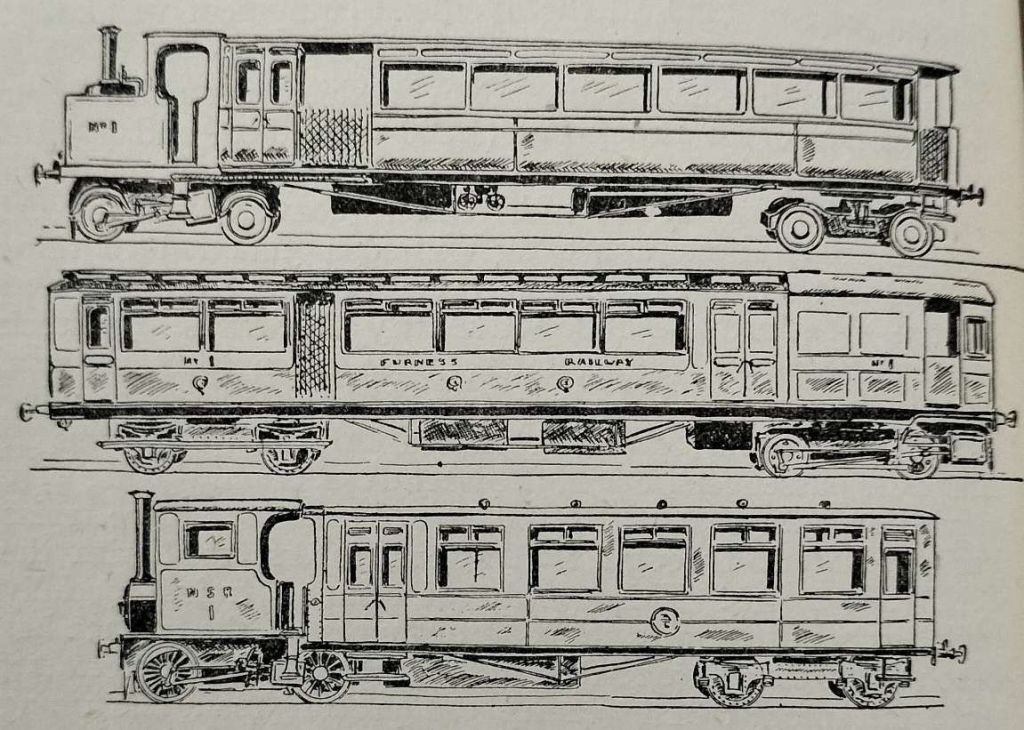

Kidner separates the period from 1847 to 1947 into three different railcar/railmotor eras: 1847-1899, 1900-1923 & 1923-1947.

1. Early Steam Railcars, 1847-1899

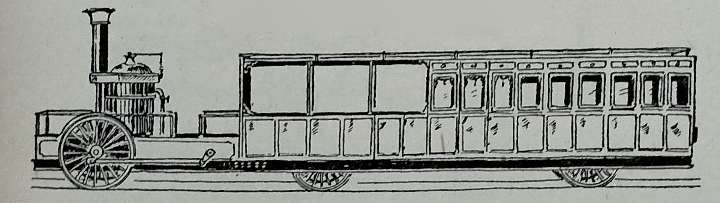

Kidner says that the “earliest railcars in the world were probably Detmole’s 12-seater cyclopede car of 1829, on the South Carolina R.R., and Andraud’s compressed-air-driven 8-seater of 1839 in France. In England, the first was the Express, a steam-driven car devised by James Samuel and W. Bridges Adams, of the Eastern Counties Railway. This little car made its inaugural trip on 23rd October 1847, from Shoreditch to Cambridge, covering the distance in three and three-quarter hours running time.” [1: p110]

Kidner notes that this diminutive vehicle successfully climbed the Lickey incline on the Birmingham & Gloucester Railway. This vehicle’s performance satisfied its designers and resulted in them building the larger six-wheeled vehicle which was 31ft 6in long. As we noted in Part 1, was named ‘Fairfield’, [2] this “became No. 29 on the broad-gauge Bristol & Exeter Railway, and worked the newly-opened Tiverton branch.” [1: p110-111]

Kidner tells us that the next railmotor, the ‘Enfield’, was built in 1849. There is a plan and elevation in the first article. [2] It was “carried on eight wheels and had seats for 42 passengers; on one recorded trip from London to Norwich 126 miles were covered in 215 minutes running time; normally, however, it worked between Enfield and Angel Road.” [1: p111]

Next year came the ‘Cambridge‘; it was a well tank (2-2-0WT) close-coupled to a four-wheeled saloon. Kidner highlights a similar unit, a “Ariel’s Girdle, built by Kitson Thompson and Hewitson and exhibited at the Great Exhibition. This combination seems never to have worked in public service in its original form, though the locomotive portion later worked the Millwall Extension line; in fact, although the rigid engine-cum-coach had given way to the handier flexible type, no great enthusiasm was shown for either.” [1: p111]

Several close-coupled units similar to the Cambridge were operated from 1852 by the Londonderry & Enniskillen Railway but otherwise J. Samuel’s invention was unsuccessful. However, his design work alongside R.F. Fairlie produced “a flexible steam-car embodying all the advantages which brought about the railcar ‘boom’ of 1903-11, virtually the only difference between Samuel’s and Drummond’s cars being that the former employed four-coupled driving wheels.” [1: p112]

Kidner says that “there is no record of this bogie car going into service. It was designed to negotiate curves of 35 ft. radius, and thus by the laying of such reversing curves at termini to avoid running round.”

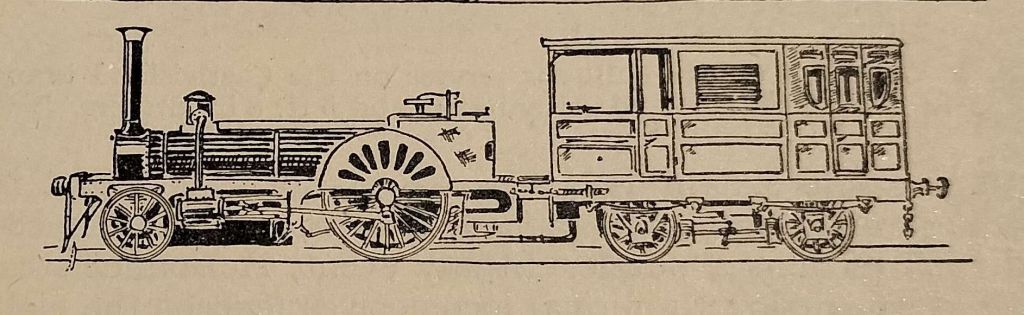

The next use of a railcar/railmotor was by McDonnell, of the Great Southern and Western Railway of Ireland.

Kidner tells us that in 1873 McDonnell built “two small 0-4-4T engines with short staff-carriages mounted at the rear, which were named Fairy and Sprite, and used for pay purposes.” A larger vehicle was built shortly after, and then two 0-6-4T cars were built in 1875 which were “35 feet long and carr[ied] eight first and six third-class passengers. … McDonnell’s cars suffered conversion to normal locomotives (except the eight-wheelers, which were scrapped), and no more railcars seen in passenger service until after the turn of the century.” [1: p112]

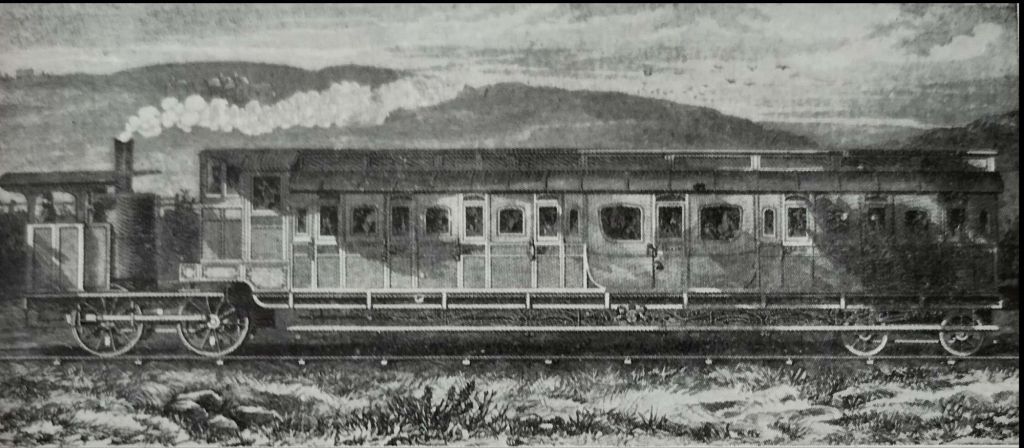

Instead, some railway companies chose to create railcars to convey railway executives across their networks.

A colourised photograph of this vehicle appeared on the Abergavenny Railways History Facebook Group

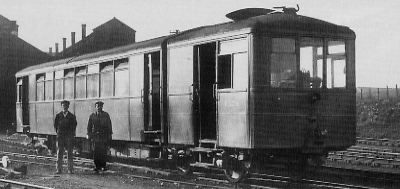

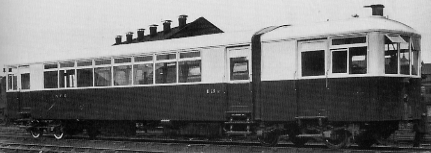

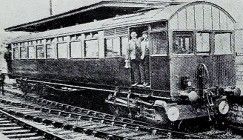

Rather than rigid-bodied cars, some lines preferred close-coupled units. One of these is shown above. Kidner says that the LNWR “ran a number of these comprising 2-2-2 engines with six-wheeled car attached, and the Wordsell brothers on the North-Eastern had a saloon fitted for reverse running normally attached to a 2-2-4T.” [1: p113]

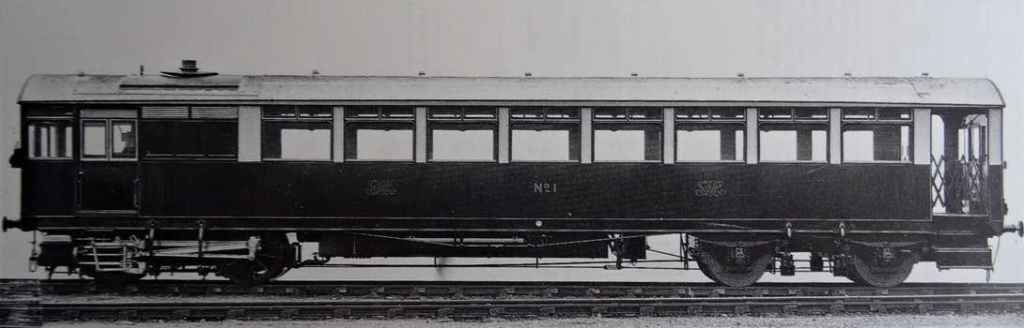

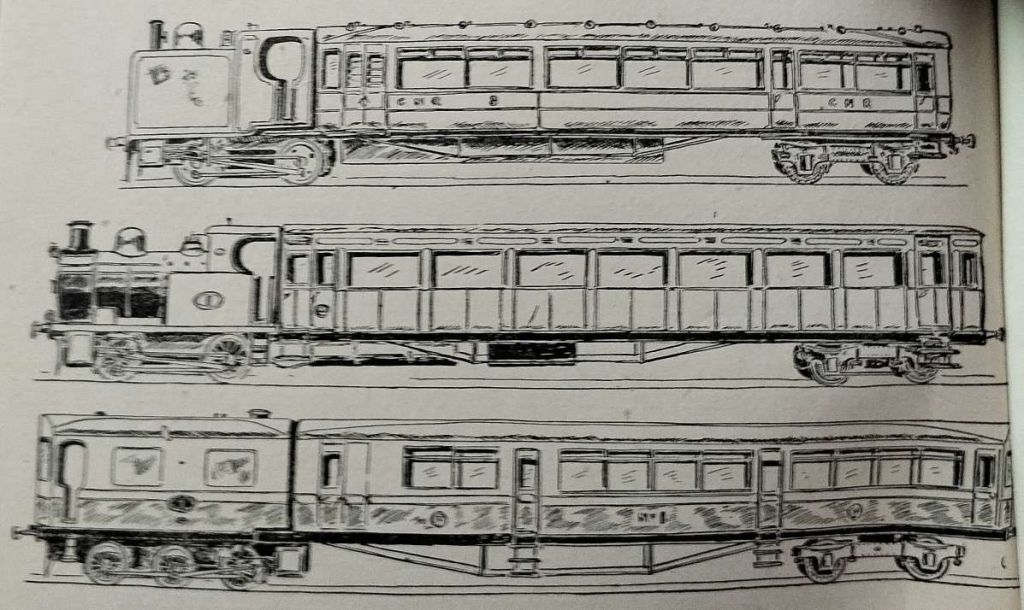

2. Later Steam Railcars, 1900-1923

Kidner talks of the contemporaries of Dugald Drummond naturally being interested in his experiment just after the turn of the 20th century. [1: p133][3] For here was a “method of providing rapid frequency without the capital outlay of electrification.” [1: p135]

Drummond’s railcar/railmotor “differed little from the Fairlie-Samuel car of thirty years ealier, though it was certainly less powerful; in fact, before going into service on the Southsea branch it was found necessary to replace the vertical boiler with a horizontal loco-type one. Unlike the old cars, however, it was fitted for control from either end, and since its ‘turn round time’ could be cut to the few seconds taken by the driver to walk fifty feet to the other end it was ideally suited for dense traffic on short branches.” [1: p135]

As we have already noted, the idea was taken up by the Great Western, in particular and by a significant number of other railway companies. [4][5][6]

Kidner notes that “these cars were undoubtedly successful when properly used, but in words spoken in 1905 by Hurry Riches, of the Taff Vale Railway, ‘when they are used to take trailer cars, and are in fact converted into mixed trains, their advantages soon disappear’.” [1: p135-136]

Almost inevitably a variety of different trailers were attached to these railcars/railmotors and as a result their key advantage was lost and their disadvantages dominated contemporary thinking. So, says Kidner writing in 1946/7, “building of steam cars ceased in 1911, and soon those already running were being converted into trailers; some of the Great Western’s 99 cars lasted until just before the late war, and at least one of the Lancashire and Yorkshire cars is running today, but of the rest few lived to see the grouping. Their inventor himself seems to have lost faith early, for in 1906 Drummond turned to separate autotrains.” [1: p136]

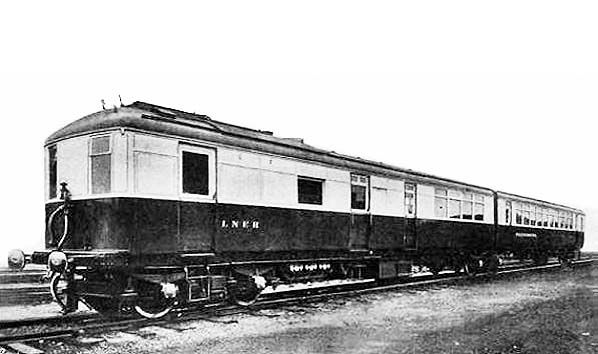

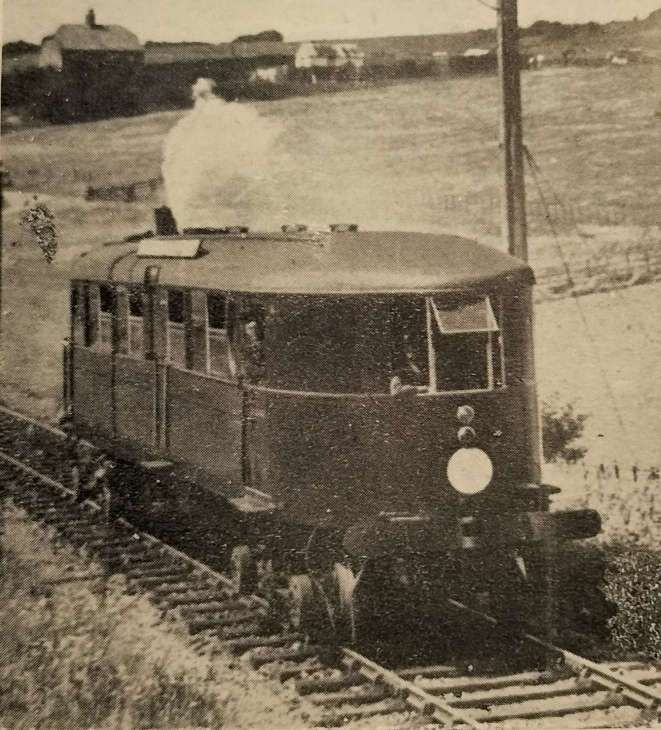

3. The Modern Steam Railcars, 1923-1947

Kidner was writing in 1946/7. For him, these later Railmotors were very much ‘Modern’. He comments: “In 1923 the branch railways were beginning to face severe competition from the buses; hundreds of such lines were being ‘carried’ by the main lines, and if they were to remain open something must be done to attract custom.” [1: p142]

We have already covered these ‘modern’ steam railmotors in Part 6 of this series. [7]

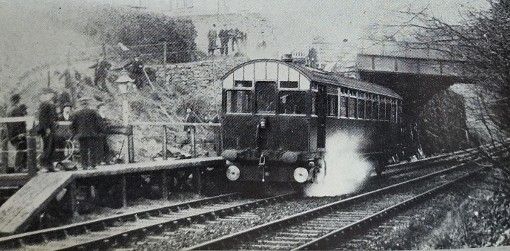

The most unusual of this later group of steam railmotors was that used by the Southern Railway on the Dyke branch. This is mentioned at the end of the previous article (Part 6) in this short series. Kidner provides a photograph of that Railmotor in action. [7] …

References

- R.W. Kidner; A Short History of Mechanical Traction & Travel – Part 6: Multiple Unit Trains, Railmotors & Tramcars 1829 – 1947; Oakwood Press, South Godstone, Surrey, October 1947, p107-150 with a series of plates before p107 and after p150.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/06/11/steam-railcars-part-1-an-early-example

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/06/15/steam-railcars-part-2-dugald-drummond-lswr-and-harry-wainwright-secr

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/06/17/steam-railcars-part-3-the-great-western-railway-gwr

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/06/18/steam-railcars-part-4-rigid-bodied-railmotors-owned-by-other-railway-companies

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/06/20/steam-railmotors-part-5-articulated-steam-railmotors

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/06/26/steam-railmotors-part-6-after-the-grouping

- https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Fox,_Walker_and_Co, accessed on 26th July 2024.

- https://modelengineeringwebsite.com/Steam_carriages.html, accessed on 26th July 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/mpoZKnE9ytwC1zRG, accessed on 26th July 2024.