Derek Hayes: The Times, HarperCollins, 2017

I picked up a copy of this book in September 2023. It is large format Hardback book of 272 pages. The listed price is £30.00 but my copy cost me just over £10 plus postage and it is in an excellent pre-owned condition. I had anticipated a well-illustrated book which would be a relatively easy read. I was pleasantly surprised to find that while it was an excellent read, it was also a well-researched, scholarly work with: all maps and illustrations properly catalogued and sources noted; a significant bibliography of scholarly works; and a comprehensive index.

Hayes’ book brings together in one volume the history of waggonways, tramways and tramroads as well as early modern steam railways. It provides some superb copies of contemporary maps. Illustrations and text are exceptionally well laid out. I thoroughly enjoyed reading through some concise introductions to significant plateways and railways of the period.

Wooden Rails and Horse/Manpower

The book begins with a review of significant lines which were first constructed with wooden rails.

– Hayes tells us that, “The earliest definitively documented application of a cross-country railed way in Britain is that of entrepreneur Huntingdon Beaumont: his waggonway ran from Strelley to Wollaton, now in the West part of Nottingham. … Documents fix the date of this first waggonway at between October 1603 and October 1604.” [1: p14]

– Other early waggonways include: some close to Broseley, Shropshire, leading to wharves on the River Severn dated at around 1605; and several feeding to the River Tyne in the 1630s. Practice differed between these two areas. In Shropshire, wagons were usual relatively small on narrow-gauge tracks which fed straight into the mines they served. In the Northeast, wagons were larger and the gauge wider.

– In Wales, a Shropshire-type of waggonway was in use in Neath, Glamorgan before 1700. In Scotland, the first available records, from 1722, cover the Tranant to Cockenzie railway close to Edinburgh which was another Shropshire-style waggonway.

We have evidence that throughout the 1700s, wooden waggonways were in use. Examples include: the Alloa Waggonway (built in 1766); Ralph Allen’s wooden railway in Bath, Somerset (built in 1731); Whitehaven, Cumbria’s waggonways which converged on staiths in the harbour (1735); the Middleton Railway in Leeds (1758); Tyneside/Northumberland/Durham (1608 onwards, significant maps have been retrieved dated 1637, 1761 and 1788). Hayes draws attention to a number of Northeast waggonways: the Plessey Waggonway; the Killingworth Waggonway; waggonways associated with Dunstan Staiths (the last of which closed in 1990!); the Tanfield Waggonway (built between 1725 and 1738); the Beamish South Moor Waggonway (built around 1780); the Pelton Moor (built between 1746 and 1787) and Deanry Moor (built 1779) Waggonways. Hayes also mentions the replica wooden waggonway at Beamish Open-Air Museum. [1: p15-31]

many extracts are shown in Hayes’ book, shows a large number of railways despite being published the same year as the opening of the Liverpool Manchester Railway. The majority of the lines shown are plateways. After an early start with edge rails, most of the lines built after about 1800 were of the plateway type. Many of these railways are referred to in the book. [1: p66-67]

The book goes on to focus on the transition between wooden and iron rails, noting the practice of overlaying wooden rails with cast-iron plates, a system which was in use as early as 1767 in Coalbrookdale, Shropshire. [1: p36]

Cast and Wrought Iron

Hayes then looks at the introduction of Cast Iron and the later Wrought (or ‘maleable’) Iron. Again two different practices developed:

– L-shaped plateways with wheels without flanges were in use underground as early as 1787, these were then used above-ground in the Shropshire area, in the Forest of Dean, on a number of lines in South Wales, and by Benjamin Outram on the Butterley Gangroad, Little Eaton Gangway and the Peak Forest Tramway. Other examples include: the Lancatser Canal Tramroad; the Ticknall Tramway; the Caldon Low Tramway; the Surry Iron Railway, the Gloucester and Cheltenham Railway; the Middlebere Plateway, Dorset; the Silkstone Waggonway Near Barnsley; The Forest of Dean and Severn & Wye Railways; the Somerset Coal Canal Railway; the Kilmarnoch & Troon Railway; and the South Wales Railway and Canal Network (including the Hay Railroad between Brecon, Hay and Kington. A departure from the us of L-shaped Cast Iron plates was the use of granite for the Haytor Granite Railway which supplied granite from Dartmoor to wharves on the River Teign. [1: p38-71]

– Edge rails with flanged wheels saw greater early use in the Northeast and on a number of lines in South Wales, although many in South Wales were converted from edge-rails or round bars to plateways because of the influence of Benjamin Outram. Those lines remained as plateways until the 1830s. Wrought or ‘maleable’ iron was initially expensive as larger section rails were used. This changed when first ‘T- section’ and then ‘I-section’ rails were produced by a rolling process. Many early edge railways used short- sections of rail in a fish-belly shape. Hayes details some of the most significant very early iron edge railways: the Forest Line of the Leicester Navigation; the Lake Rock Rail Road; the Belvoir Castle Railway; the Mansfield & Pinxton Railway; the Plymouth & Dartmoor Railway; the Stratford & Moreton Railwaythe Monkland & Kirkintilloch Railway and its later siblings, the Garnkirk & Glasgow Railway, and the Ballochney Railway; the Slate Railways of North Wales, (including the Llandegai, Penrhyn, Nantile and Dinorwic Railways); and the Northeast Coalfield. [1: p72-93]

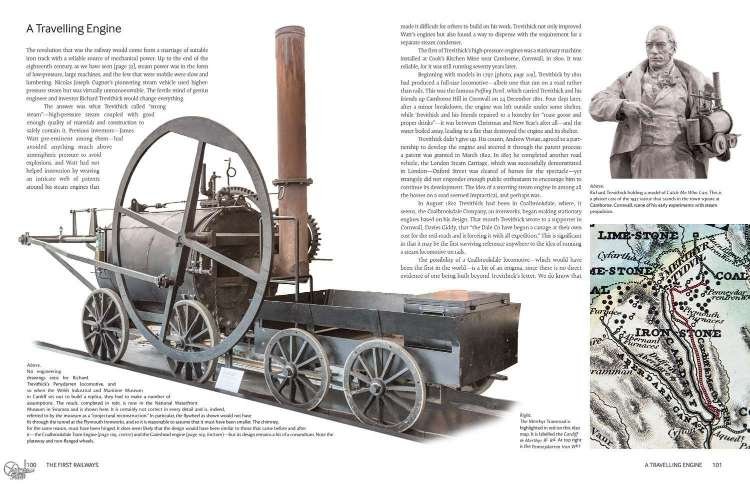

A short section [1: p94-99] covering inclined planes and stationary engines precedes Hayes coverage of the first ‘Travelling Engines’ and ‘Working Locomotives’ in the ear before Stephenson growing ascendancy. [1: p100-127]

Steam Power

Richard Trevithick was to be the person who solved the question of how to use steam-power on rails as a Travelling Engine. It required the use of high-pressure steam. …

A good introduction to George Stephenson’s early activities [p128-133] is followed by a focus on the Hetton Colliery Railway which, after a competition between engineers, George Stephenson designed with three self-acting inclines and level sections worked by horses or by his locomotives. By the date of opening, Hetton Colliery Railway became the first to be designed specifically for locomotive use and featured three of Stephenson’s ‘patent travelling engines’. “Just over half the route was worked by locomotives. … The other five sections were all inclines. Three were worked on a self-acting basis and two … used engines. Despite being advised by Stephenson … to use maleable- or wrought-iron rails, the Hetton Colliery Railway used …cast-iron edge rails, each 3ft 9 ins long and laid on stone and wooden blocks. They gave the company a lot of trouble. … Despite considerable on-going modifications, … the railway proved conclusively the value of the locomotive engine and provided valuable experience for Stephenson. … [It] lasted for well over a century: the last section closed only in 1972, the result of the decline of the coal industry rather than issues with the railway.” [1: p134-139]

These early railways were local affairs but there were visionaries who perceived that longer distances would soon become possible. Hayes points us to: Benjamin Outram, who proposed a double-track railway from London to Bath; Richard Lovell Edgeworth, who in 1802 published a paper entitled ‘On the Practicability and Advantage of a General System of Rail-roads‘; Thomas Telford, who surveyed a 125 mile route from Glasgow to Berwick in 1809-10, recommending the use of a railway rather than one of his favoured canals; John Stevens (in the US) who argued that railways would be better than canals over longer distances; William James, who in 1802 proposed railways from Bolton to Manchester and Liverpool, and who, in 1808, proposed a General Railroad Company to build a network of railways across Britain; Edward Pease, in 1821, imagined a London to Edinburgh railway; and Thomas Gray, who in 1820 was the first to proposed a detailed railway network covering all of the British Isles which could be used for poor-relief by creating massive levels of employment during its construction. [1: p140-143]

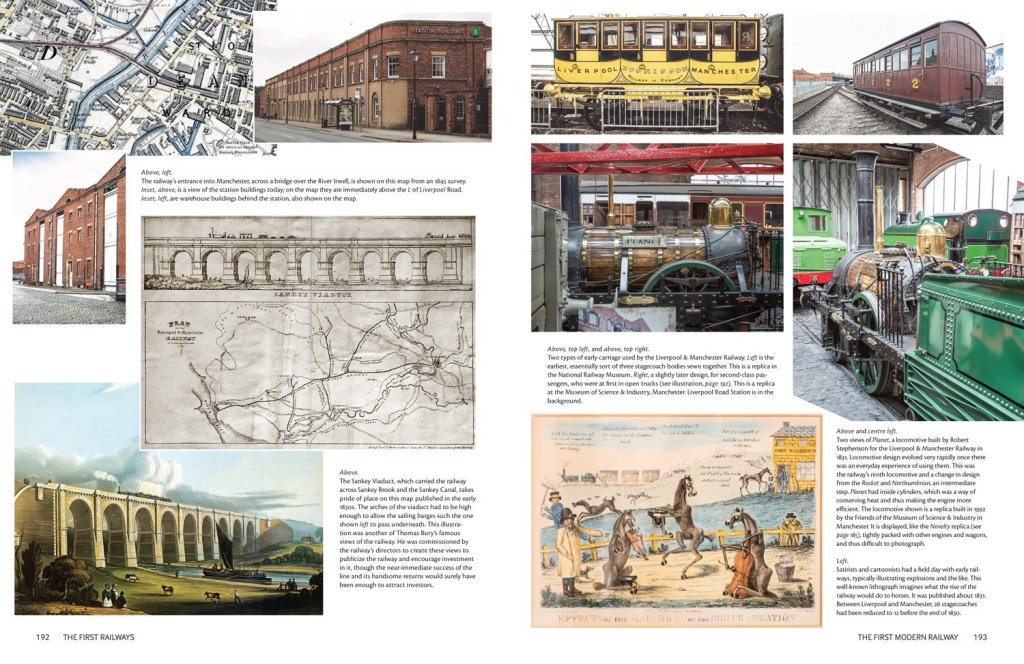

Detailed studies of the Stockton & Darlington Railway [1: p144-167]and the Canterbury & Whitstable Railway [1: p168-171] precede discussion of what Hayes calls ‘the First Modern Railway’, The Liverpool & Manchester Railway. Hayes provides a detailed and well-illustrated ‘chapter’ about that railway, including contemporary maps and images. [1: p172-193]

Further short studies look at: Agenoria’s Railway and at the batch of locomotives, of which Agenoria was one, the other three being exported to the united States, one of which (the Stourbridge Lion) became the first steam locomotive to run in North America in August 1829; the Cromford & High Peak Railway; the Leicester & Swannington Railway; and the Stanhope & Tyne Railway. Honourable mentions include: the Bristol and Gloucestershire Railway; the Avon & Gloucestershire Railway; the Whitby & Pickering Railway; and the Bodmin & Wadebridge Railway.

Hayes then reflects on the gradual development of a national network of railways and a growing number of skilled railway engineers, [1: p206-225] before picking out one railway, the London & Greenwich Railway, which has a claim to have been the first commuter railway. [1: p226-229]. Hayes closes his book with a short look at the transfer of railway technology from the UK to the rest of the world. [1: p230-259].

Summary

In summary, Hayes book is, as the rear of the dust-jacket claims, “A highly illustrated and readable account of the earliest railways, from the first wooden-railed waggonways to the development of the railway network of the 1840s and beyond. During this period the modern railway engine was invented and refined; it rapidly outpaced the horse and developed into a swift and strong machine that changed the course of world history forever.” [1]

There are 700 maps and other illustrations and the story is brought to life by a lively narrative supported by well chosen photograph and railway ephemera.

The book is something of which its author can be justifiably proud. I thoroughly recommend it’s inclusion on the library of anyone interested in the development of the railways from their early beginnings. It is worth its cover price of £30.00, but if you can find it in good condition for around £10.00 second-hand, then jump at the opportunity to make a purchase!

References

- Derek Hayes; The First Railways: Atlas of Early Railways; The Times, HarperCollins, Glasgow, 2017. [2]

- https://www.amazon.co.uk/First-Railways-Derek-Hayes/dp/0008249482, accessed on 14th September 2023.

Hey, that is nice. Just saw note on Early Rail group. This is the era I really, really, wanted to model in O, or better G, when I was a teen in the 1970s-1980s but there were no appropriate wheels available here in the US. And I had neither the knowledge, money, nor access to machine shop tools, for making them.

It is a good book!

I just did a presentation on first generation steam at the local history chapter. Wish I’d seen this first! What a treasure. Have you written on the Rocket? I distinctly recall reading a passage that purported Stephenson, Sr. had remarried a third time to a popular British actress half his age, and was seen galavanting across the landscape in a later conjuration of locomotive, something like the Planet, with his lovely bride on the foot plate holding on to her hat as they wheeled up to shocking speeds of 40 MPH.

My attempts to relocate this (fanciful?) passage failed, and I could only find references to his third wife as being a milk maid, or a daughter of milk maid, from some unglamorous spot on the map. Is this rubbish, or any hint of truth?

I follow your numerous expositions frequently; they are most excellent.

Regards,

Jeffrey McNeal

(Chops)

El Paso, Texas

Sorry, Jeffrey. I don’t know. I’ll keep an eye open as I read!🙂