The Railway Magazine of September 1922 carried two short articles about new petrol Railmotors. …

North Eastern Railway (NER) – Petrol Rail Motor Bus

The first short article was about an experimental vehicle used by the NER.

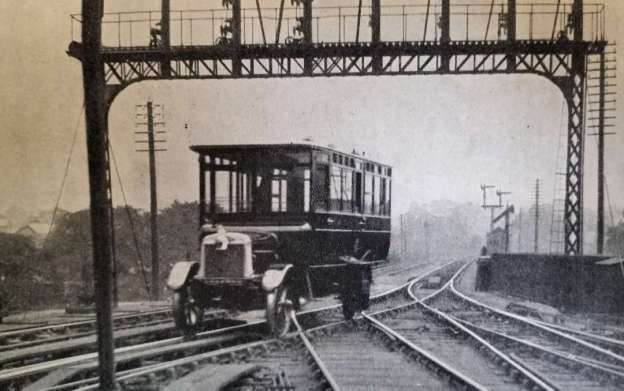

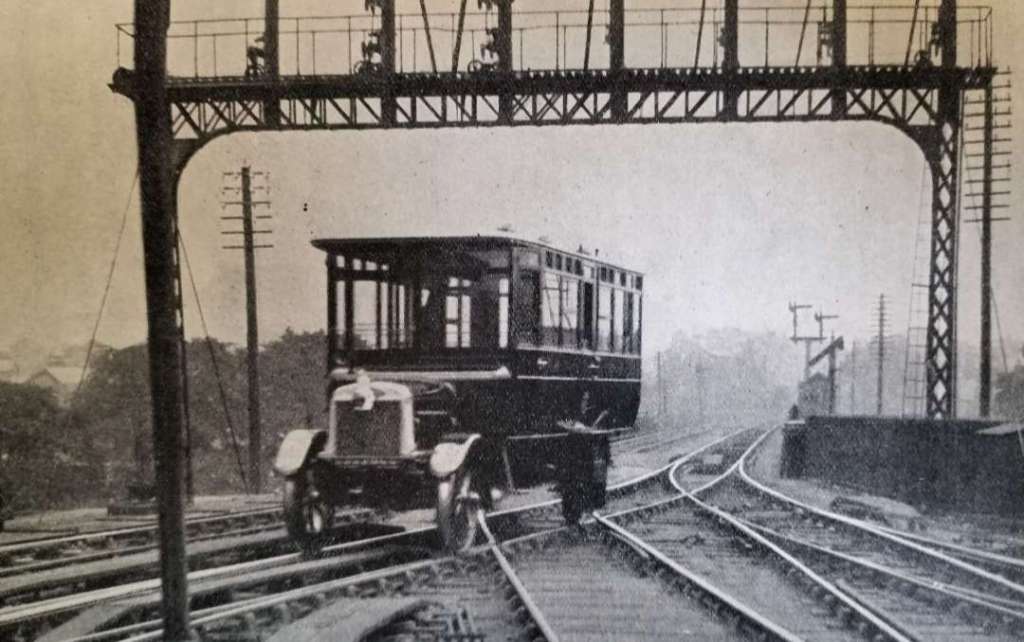

On certain portions of the NER network, the company realised that “there was room for a service conducted on lines as nearly as possible identical with those of motor buses on the roads. With the view of ascertaining, without much initial expenditure, whether the scheme is likely to prove financially successful, they have converted one of their ‘Leyland’ road motor ‘buses, formerly running on the road services in the vicinity of Durham, so as to make it suitable for running on the railway.” [1: p234]

The war resulted in a significant increase in railway working expenses which made it impossible to provide a train unit on some of the country branches, where the number of people travelling was small, “sufficiently cheap to cover its working expenses out of the small revenue available,” [1: p234]

The NER needed to devise a cheaper form of rail transport. As a first step, it decided to convert one of its own fleet of petrol-powered road buses. The company’s intention was to undertake a trial at low cost before developing a design specifically tailored to rail use.

The experimental unit entered service on 19th July 1922. If “the results of the working of this vehicle are encouraging, the company intend[ed] to build vehicles [capable of] carrying up to 40 passengers, and maintaining an average speed of approximately 30 m.p.h.” [1: p236]

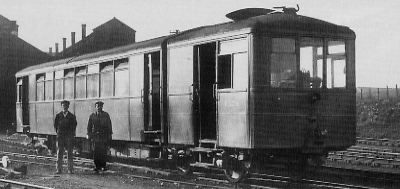

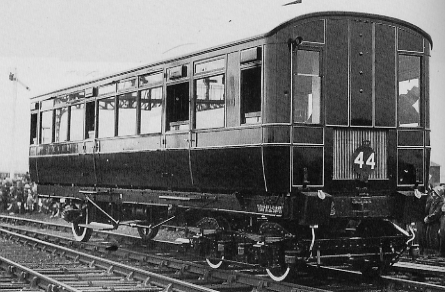

The railmotor operated between Copmanthorpe, York, Strensall and Earswick, and was “manned by a motorman and a conductor exactly in the same way as if it were running on the highway. Single journey tickets [were] issued on board, so that passengers [did not have] the trouble of going to the booking office. It [had] accommodation for 26 passengers. It [ could] be driven from both ends, and run in either direction, and the motive power consist[ed] of a 35-h.p. Leyland engine of the standard type, supplied by the builders for their ordinary commercial road vehicles.” [1: p236]

The donor vehicle was one of three Leyland Motor Co. buses that the NER purchased on 21st July 1921. “With a long bonnet and a overhanging roof at the front, it was a typical design for that time. The conversion was completed at York Carriage Works. Initially No. 110 in the Road Vehicle fleet, it was renumbered as No. 130Y shortly after conversion because No. 110 was already occupied in the Coaching Stock list.” [2]

An “additional radiator and an additional driving position were located at the rear of the vehicle. Central passenger doors were fitted to both sides of the saloon. …. Folding steps were also added to allow access from rail level. These were later replaced with fixed steps, and eventually removed altogether. An electric headlamp was also fitted.” [2]

The LNER website continues: “the initial York duty involved a service to Haxby, Strensall, Earswick, and Copmanthorpe. NER Petrol Autocar No. 2105 took over this duty on 9th July 1923, and No. 130 was transferred to Selby. At Selby, No. 130 operated daily return trips to Straddlethorpe, York, Goole, Catleford, Goole, Market Weighton, Cawood, and Hemingborough. This resulted in a full timetable that started at 6:52am and finished at 7:44pm. No. 130 took part in the Stockton & Darlington Centenary celebrations, but continued these Selby duties until November 1926.” [2]

On 11th November 1926 the railmotor/railbus “caught fire whilst being filled up with petrol at Selby shed. The entire bus was reportedly gutted within 15 minutes. Reports also suggest that someone used a naked paraffin lamp to check the level of the petrol tank. Only the chassis remained, and it was eventually decided not to rebuild or replace the bus. No. 130 was officially withdrawn from stock on 9th April 1927.” [2]

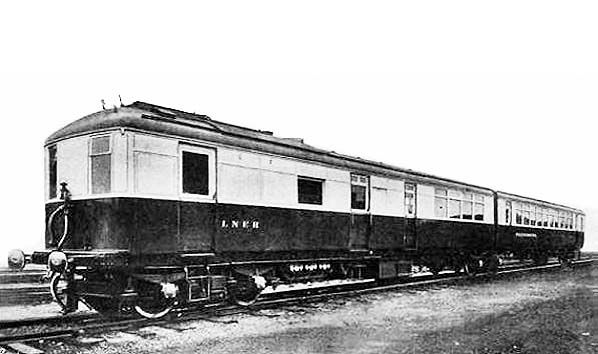

It seems as though the initial experiment was successful enough to allow the NER to authorise the building of a further experimental petrol railmotor (No. 2105) in September 1922. A Daimler engine was purchased in October and “the remainder of the vehicle was built at York Carriage Works and was completed in July 1923. By this time, Grouping had occurred, and the autocar was given the LNER number 2105Y. It was later renumbered as No. 22105 in August 1926.” [3]

It seated 40 in third class accommodation, seats were in pairs either side of a central gangway. “The distinctive wheel arrangement had a two axle bogie at the engine end, and a single fixed axle at the other end. The single fixed axle was powered from the motor via a clutch, three-speed gearbox, and propeller shaft with two universal joints. 40mph was reportedly possible. Radiators were fitted to both ends.” [3]

This Railmotor took over the service provided by No. 130 and continued to operate local services in and around York until 1930. By 1930, it had been renumbered 22105.Closure of a series of local stations that year led to it being reassigned to the Hull area. It is “known to have been given an extensive timetable in the Hull area from 1st May to 17th July 1932 when it worked a 14 hour timetable including Beverley, Thorne North, Brough, Willerby & Kirk Ella, and Hull. Reports suggest it was unreliable during this period and was often replaced by a Sentinel steam railcar.” [3]

Over the next two years, No. 22105 did not work any revenue-earning services. It was withdrawn from service on 19th May 1934.

What is perhaps surprising is that these two experimental vehicles were not the first ones used on the NER network. The NER had experimented with petrol railmotors just after the turn of the 20th century. Two examples are worthy of note.

A. Petrol-electric Railmotors/Autocars

The NER were reviewing their operation of suburban passenger services on Tyneside. Alongside the introduction of electric trains on an urban network of lines which would later develop into the Tyne and Wear Metro, the NER ordered two experimental railcars/railmotors to work other, non-electrified, parts of the network.

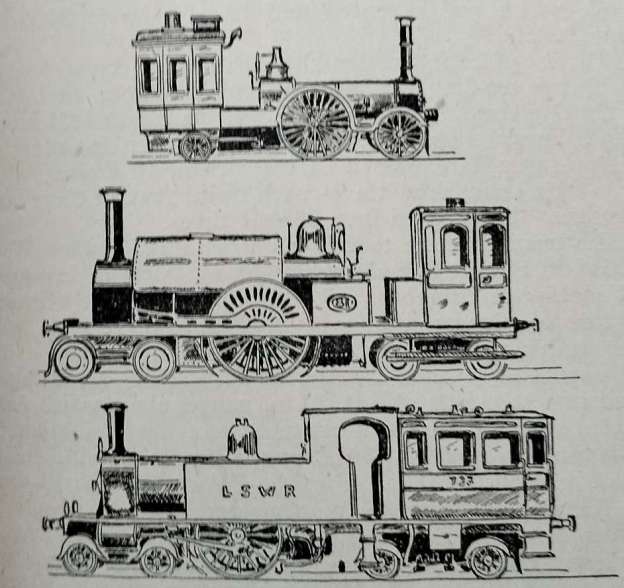

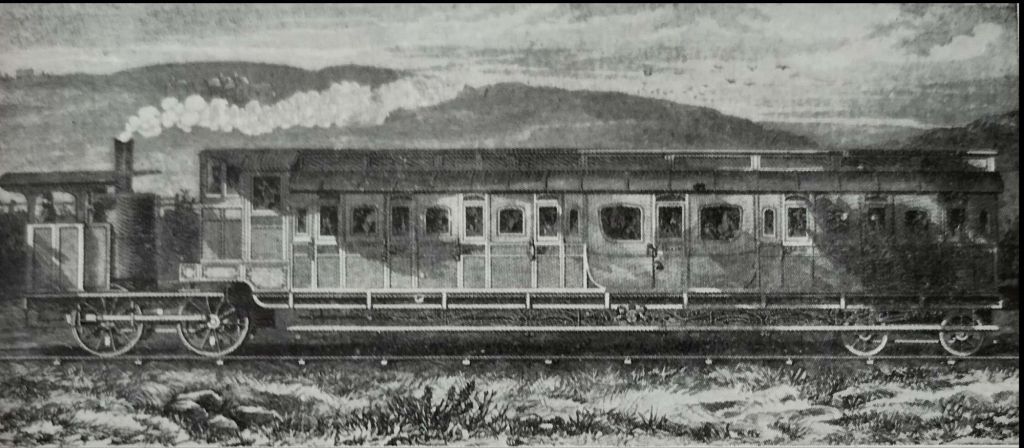

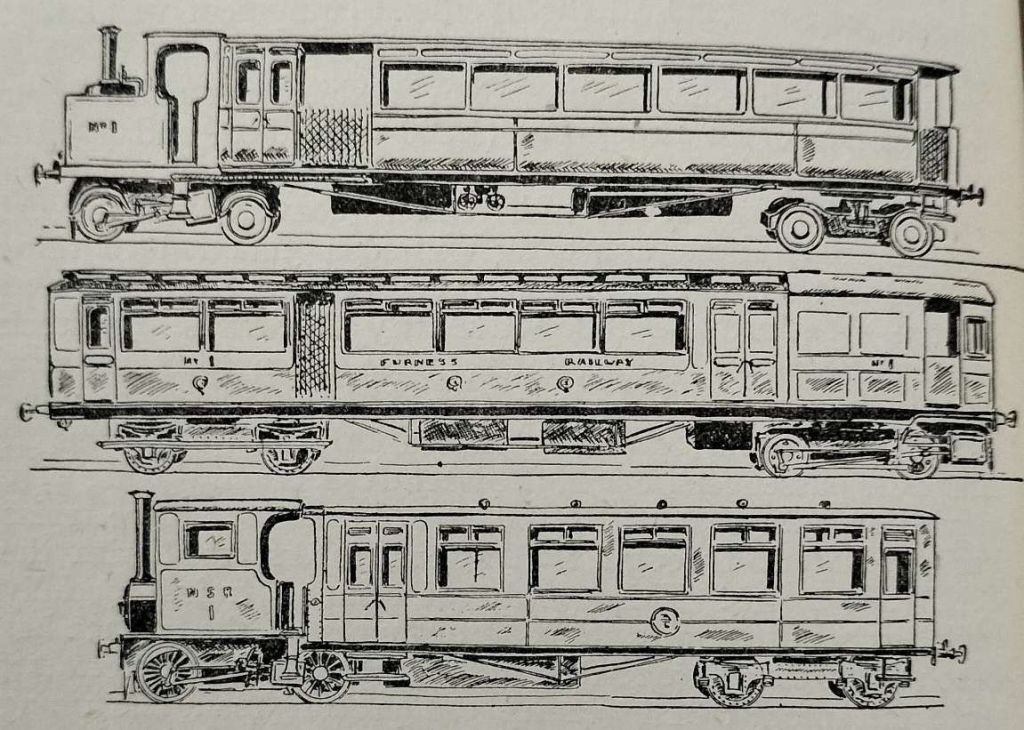

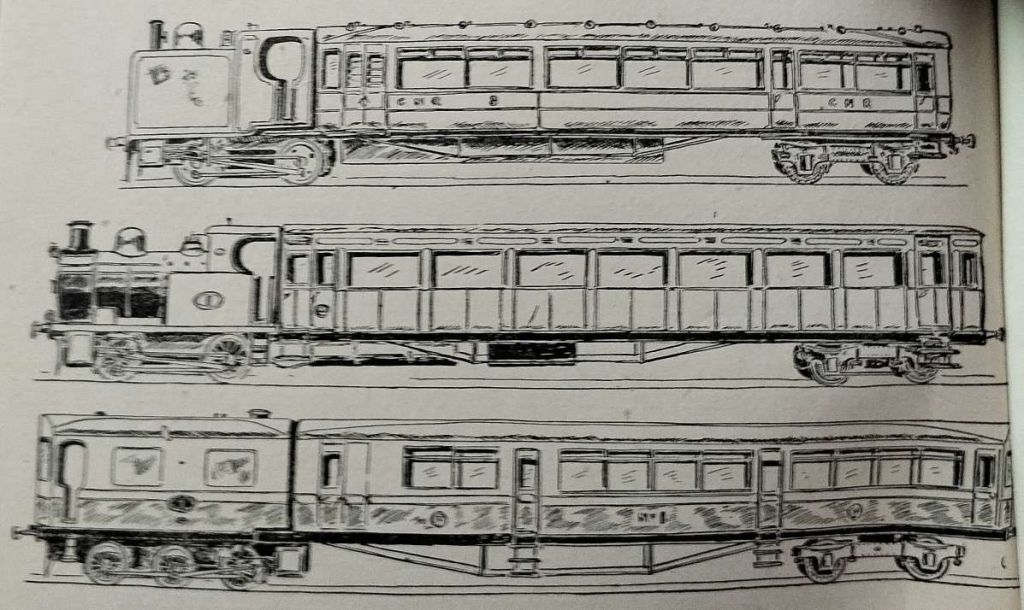

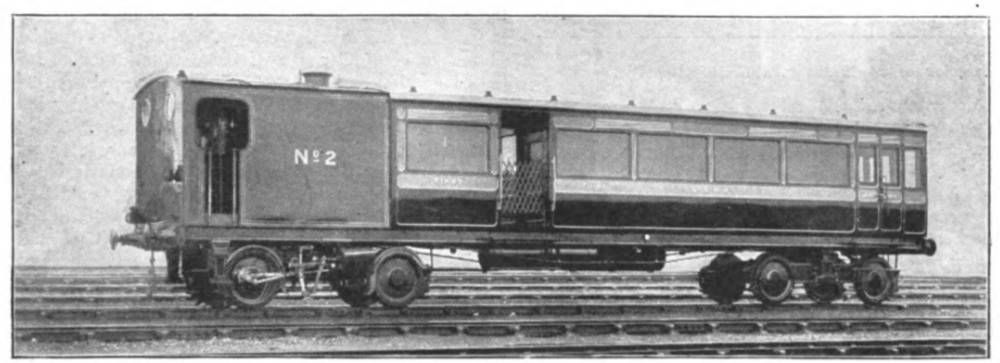

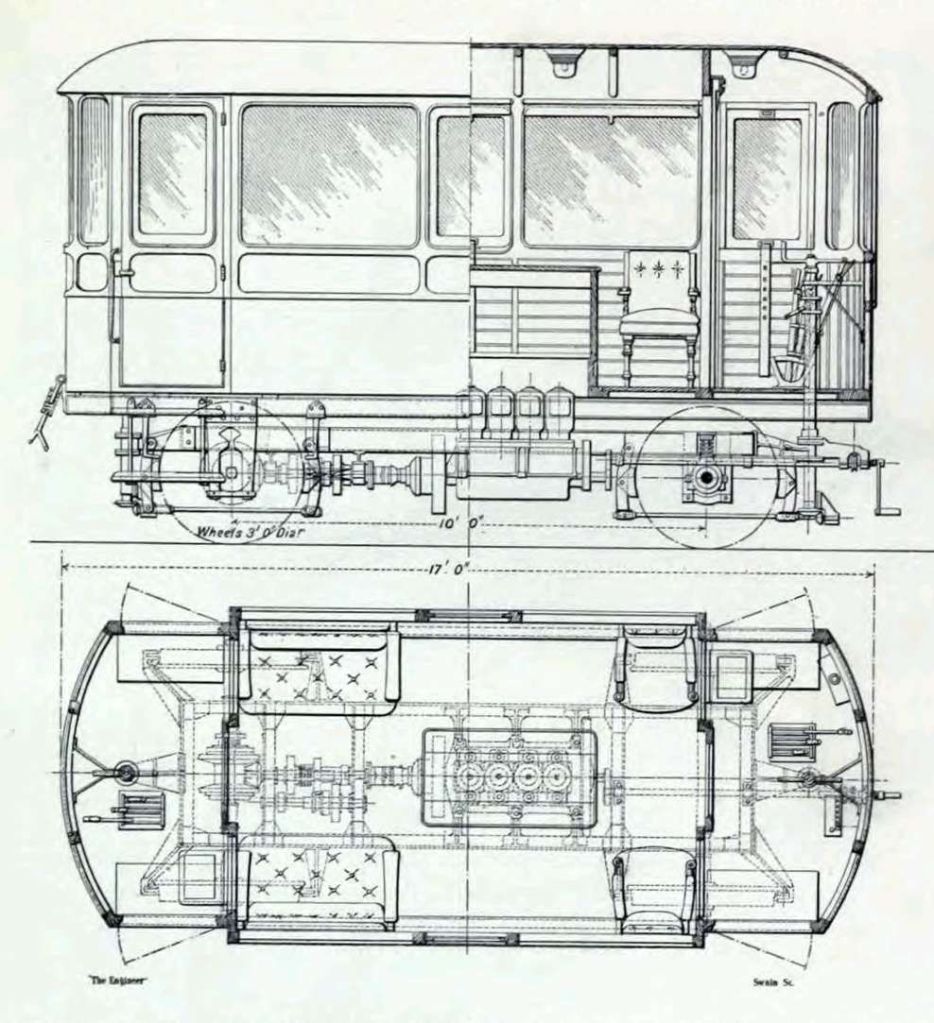

“Both railcars were built at the York Carriage Works, together with the original Tyneside electric stock, in 1902-3 and numbered 3170 and 3171. They were 53.5 feet long and weighed around 35 tons. They had clerestory roofs, bow ends, large windows and matchboard sides. There were four compartments inside, the engine room with the principal driving position, a vestibule, the passenger saloon and a driving compartment. There was no guard’s compartment. The passenger saloon had 52 seats. These were reversible and upholstered in standard NER pattern. With curtains at the windows, radiators between the seats and electric lighting, the passenger accommodation was described as ‘cosy’ and seems to have been very popular with the travelling public.” [4]

These two railmotors were referred to as ‘autocars’ after the steam push/pull autotrain services already operated by the NER.

The Embassy & Bolton Abbey Railway comments: “These NER railcars were the first in the world to use petrol-electric technology. At that time, diesel engines were less advanced and not as reliable as their petrol counterparts. The concept of using internal combustion engines to power electric traction motors would later be developed into the diesel electric technology used to power many of BR’s ‘diesel’ locos.” [4]

Initially the railmotors/autocars saw service “between West Hartlepool and Hartlepool stations (in direct competition with electric tramcars) and Scarborough to Filey (as a replacement of a steam service). Later, the autocars were transferred to the Selby – Cawood branchline to work the passenger services there. In 1923, no.3170 was fitted with a larger engine and new generator giving it sufficient power to pull a conventional carriage, thus increasing passenger capacity. It worked in the Harrogate area for a while before rejoining its twin on the Cawood branch. No. 3171 was withdrawn in 1930 and No. 3170 in 1931.” [5]

These vehicles had a petrol engine and a generator in their engine rooms, producing electricity for two Westinghouse 55HP traction motors which were mounted on the bogie underneath. A series of different petrol engines were used during the life of these vehicles. “In 1923, no. 3170 was given a third engine, a 225HP 6 cylinder ex-WD engine rumoured to come from a First World War tank. This new engine gave 3170 more torque and enough power to haul an autocoach as a trailer, though it seems not to have affected the maximum speed.” [5]

The LNER showed an interest in these vehicles and went on to test Armstrong diesel-electric railcars in the 1930s, but by then Sentinel steam railcars had been introduced. “These were not as reliable or popular, they had more seats and fitted better into the contemporary infrastructure.” [4]

No. 3171 was dismantled when withdrawn. When No. 3170 was withdrawn on the 4th April 1931 it was transported to Kirkbymoorside near Pickering, where the body became a holiday home. “Fitted with a tin roof and veranda it was well protected from the weather and survived there until September 2003 when it was sold to carriage restorer Stephen Middleton who moved it to the Embsay and Bolton Abbey Steam Railway.” [5]

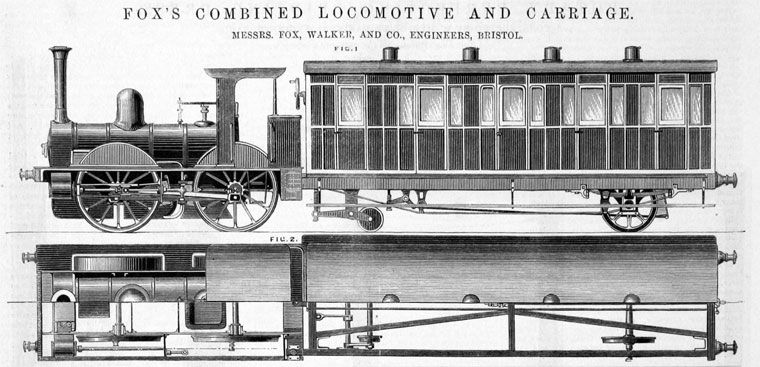

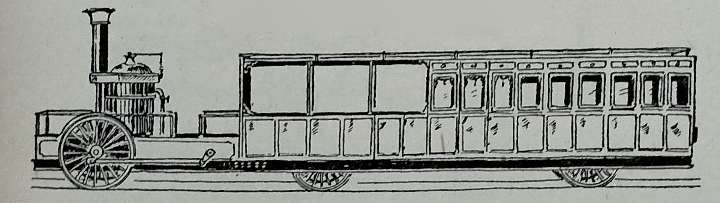

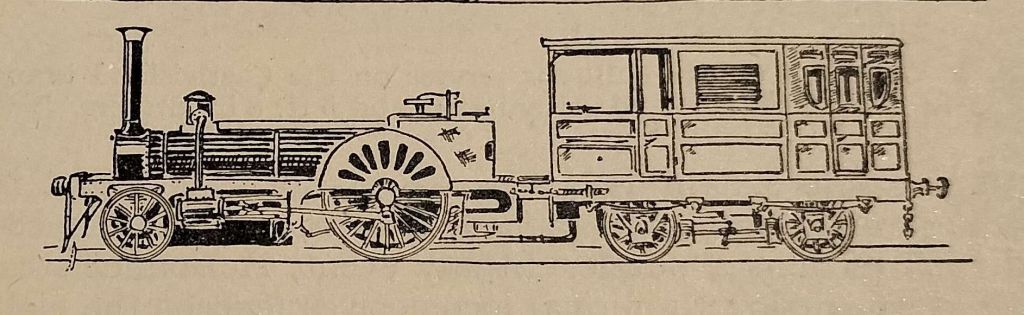

B. A Petrol Directors’ Vehicle

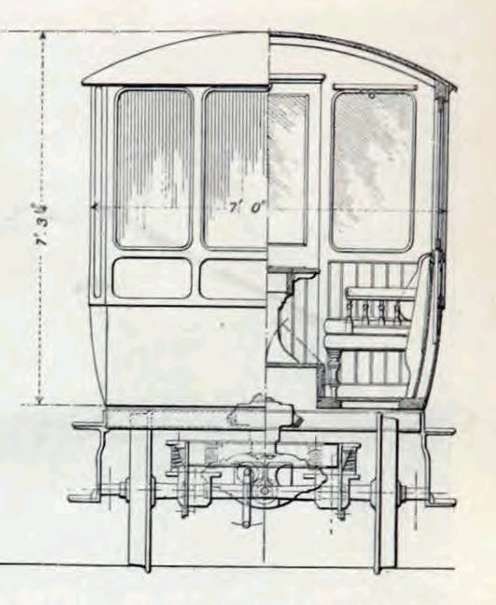

The Engineer reported in early 1908 that “The North-Eastern Railway Company [had] recently built at its York carriage works and introduced into service a petrol rail motor inspection car designed for the use of its executive officers. The car [was] 17 ft in length by 7 ft in width, with a wheel base of 10 ft. It [was] arranged with a driver’s compartment at each end, and with an open saloon 10 ft. long in the middle. The saloon [was] entered through either of the driver’s compartments, and there [was] a permanent seating accommodation for six passengers, whilst two extra seats [were] provided on camp stools.” [8: p358]

It seems reasonable to ask why, with the experience gleaned in the very early years of the 20th century, the NER felt the need in 1922 to commission further experimental vehicles. Was it because the technology had developed significantly? Had the early experiments been less than satisfactory?

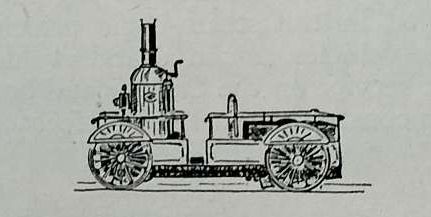

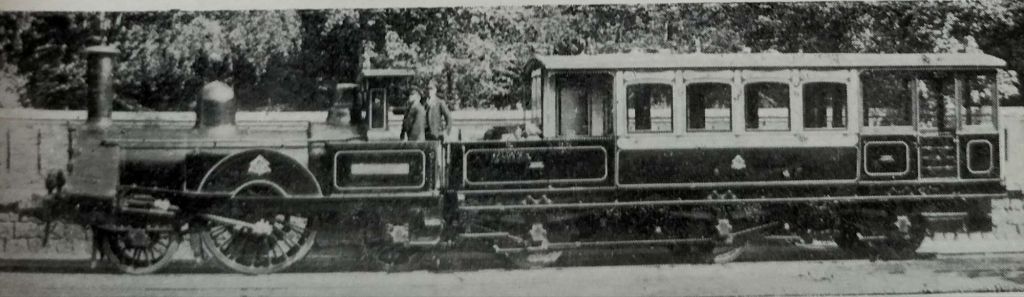

Weston, Cleveland & Portishead Light Railway

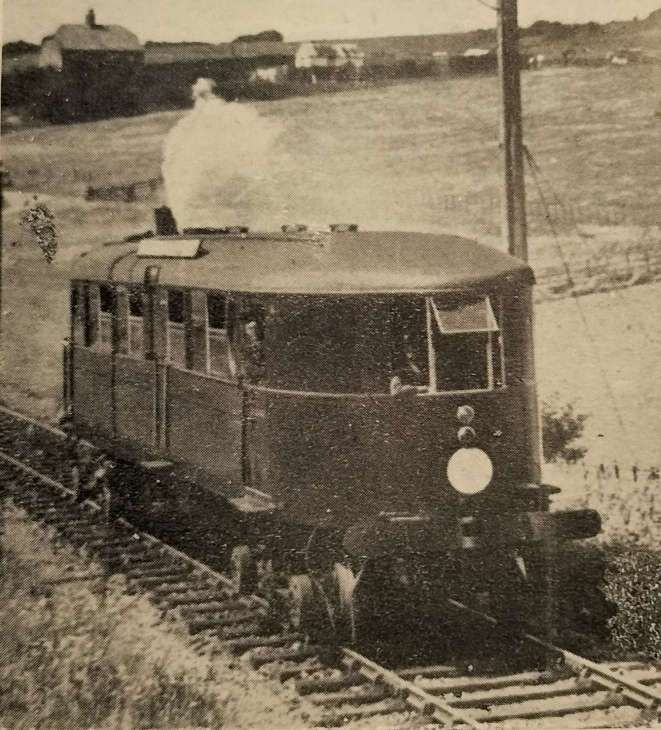

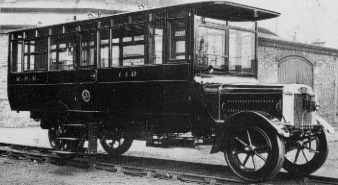

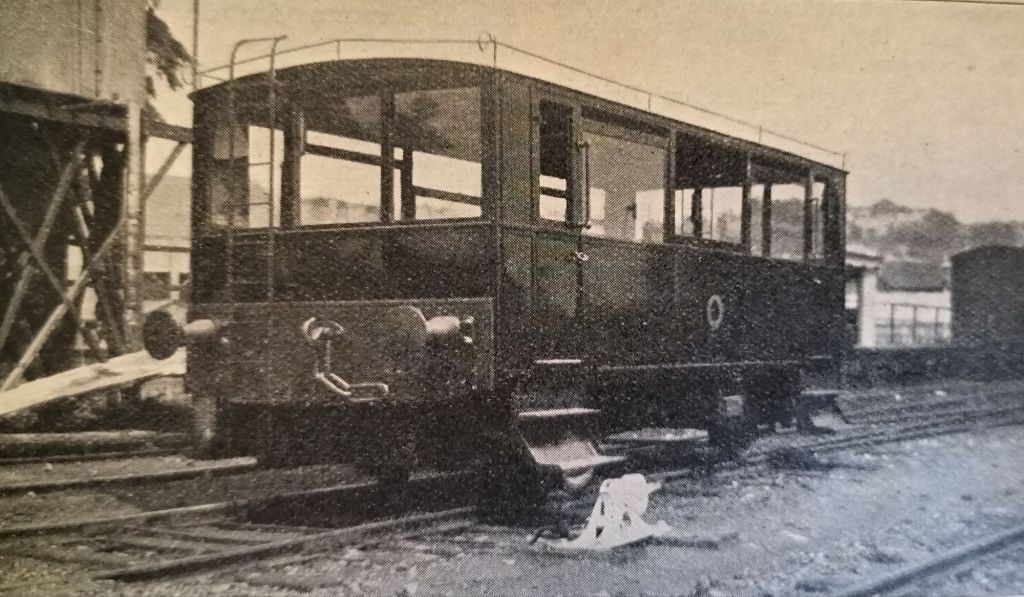

The second short piece in The Railway Magazine of September 1922 related to a Railmotor constructed by the Drewry Car Company Limited (Works No. 1252), to the instructions of Colonel H.F. Stephens, who, along with other roles, was Engineer and General Manager of the Weston, Clevedon and Portishead Light Railway.

The railmotor was powered by a 4-cylinder Baguley 35 hp petrol engine with a 3-speed gearbox and its oil consumption, on easy gradients, [was] 16 miles to the gallon. It had a maximum speed of 25 mph. It was 19ft long and driven by a chain drive from either end. It had 2ft diameter wheels. [1: p239][6]

The vehicle had full visibility all round. Glazed throughout above waist height. Side widows were openable. The panels below the windows were of steel. Acetylene lighting was provided for travel after-dark. The unit carried a maximum of “42 passengers – 30 sitting and 12 standing. The car [was] provided with rails round the roof to enable light luggage and market produce to be carried outside, thus giving the passengers more accommodation.” [1: p239]

Colonel Stephens “was a pioneer of petrol traction. The WC&PR was the first of his railways to introduce railcars. … Due to low running costs [the Drewry Railmotor] was relatively profitable. … Originally the petrol tank was fitted inside the railcar together with spare cans of petrol. As smoking was then common, it was later realised that this was a hazard and a cylindrical horizontal petrol tank was fitted at one end above the buffer beam.” [6]

“A light four-wheel wagon built by Cranes was bought in 1925 for the railcar to carry extra luggage or milk churns.” [6]

References

- The Railway Magazine, Westminster, London, September 1922.

- https://www.lner.info/locos/IC/ner_petrol_bus.php, accessed on 8th August 2024.

- https://www.lner.info/locos/IC/ner_petrol_autocar.php, accessed on 8th August 2024.

- https://www.embsayboltonabbeyrailway.org.uk/oldsite/nerautocar.html, accessed on 8th August 2024.

- https://electricautocar.co.uk, accessed on 8th August 2024.

- https://www.wcpr.org.uk/Railcars.html, accessed on 8th August 2024.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ashcombe_Road_-_WCPLR_small_railcar.jpg, accessed on 8th August 2024.

- The Engineer; 3rd April 1908, p358 and 1st May 1908, p460.