More from the SJK Postvagen Forum. As noted in my previous article, I have used Google Translate to perform a basic translation of each piece and then I have sought to clarify and paraphrase what has resulted from the automatic translation. I trust that this continues to be of interest. …

in this post we have lengthy ‘excerpts’ from a book by Ingolf Boison, the director of a documentary made about the Railways of Iran just before the outbreak of the Second World War. It is very clear, when watching the full film, that construction of the lines shown had only very recently been completed. The book: Banen Skal Bygges Paa Seks Aar (The Railway Built in 6 years). The film: “Iran – Det Nye Persien.” Details of the film are provided in the references below. The film is worth watching, however, the commentary is in Danish. [1][2] The book tells a great story and with translation software it is all worth reading. I have limited myself to just translating the text where there are links (however tenuous) with the railway itself. Most of the references within the text are to the Northern section of the Trans-Iranian Railway.

1. The material in italics below is translated from the original Danish. It is a lengthy, but interesting account! it is made up of chapters from a book about the filming of a hour long documentary. The original Danish text can be found on the SJKPostvagen platform. In some places the text has been slightly abridged. [1] Chapters 6, 7 and 8 are immediately below. [1: p38-78]

Chapter 6: A Deal made with a Handshake – We did not come to Iran as tourists, we had a big job ahead of us and we’re keen to start. We were staying with Engineer Saxild in his splendid home on the outskirts of Tehran, ‘Villa Kampsaxa’, and as soon as we had unpacked, the discussions about preparing for filming began. We did not have a ready-made screenplay from home, not even a fixed plan for the film’s story. The request to undertake this project came at very short notice, we did not have time to sit in Copenhagen and write a screenplay for a documentary film about “Iran and the Trans-Iranian Railway” – which was the assignment that we had been giving assignment solved. Engineer Saxild had travelled to Tehran a week before us, and prior to his departure he had only had the opportunity to briefly tell us about the country and the work. We had looked at maps and studied photographs and had realized that it was a great story that we were going to try to squeeze into a movie of an hour’s length. It was not just a cinematic task showing the work of Danish Engineers in a strange land. It was much more than that.

We are so insular at home in Denmark, that we neglect our skilled people’s efforts abroad. Very infrequently do we have their work documented.This film was very important and had to succeed if Danes were to understand the work completed by their countrymen alongside comrades from Sweden and Norway. The collaboration between Nordic engineers made a deep impression on one, it was essential for the success of the work. This well-oiled organization, involved 55,000 Workers working 600 million hours, 0.5 million tons of Cement, 2 million cubic metres of masonry, 1.5 million sleepers and 10,000 tons of rail, to build 1000 km of railway in Iran, and the contract was agreed with a handshake.

Could we manage to explain to people at home how the Nordic Community works out here in the Orient? How Swedes and Norwegians are not just nice people from a couple of neighboring countries, partners together with us. It was not only at enjoyable gatherings in the Scandinavian Club or in the spartan engineering houses on the line that one felt it, but across the whole working community, which for eight months we were permitted to be a little part of. Real Nordic co-operation is occurring down here, and it the rhythm of this work and its results that we have been tasked with portraying. The task required all our energy. Great confidence was shown in us, and at times the responsibility was almost crushing.

Initially, there was no talk of a Danish version of the film at all. For the time being, a Persian version was to be made which was intended to honor the Shah, and a French version, which could shown to the many employees of the Kampsax Consortium and their relatives.

After our first night in Villa Kampsax, we sat in the evening in a corner of the large living room, talking movies. An acute attack of gastroenteritis had forced me into a rather unplanned retreat when the dessert was served. I was now sitting, trying to cure my stomach with with strong Coffee, Cognac and a good Danish Cigar. I was trying, together with Axel (Lerche), to find out how a Danish engineering company was sat here in Tehran as Counselor to the Shah and responsible for the construction of 1000km of railway, part of which runs through some of the world’s most inaccessible mountain regions. Engineer Saxlld had invited five of his employees to this share lunch with us and to participate in the planning of our work. We had already received a wealth of factual and technical information on the construction of the Trans-Iran Railway, but we asked to hear the about whole adventure from the beginning. Who better to tell us than those we were with that evening.

Engineer Erik Kayser (the Technical Director for the Southern end of the line from Tehran to the Persian Gulf) sat next to our host. Chief Engineer Mogens Blach was also with us. He was the overseer the construction of the Southern Line and also undertook the survey of the line. Also with us were, the jovial Norwegian, Karl Olsen, Chief Engineer for the completed Northern Line between Tehran and the Caspian Sea, Engineer Aage Jensen, who was looking to help us organize filming on the Southern Line, and the Kampsax Consortium’s Secretary General, John Petersen. All were tried and tested veterans in the employ of the Consortium.

“Everything started at Trollhåttan as far back as 1913,” said Engineer Saxild. “The Danish engineering firm Saabye & Lerche, which had carried out several contracts in Sweden, had been assigned to build a small section of the railway from Trollhåttan to Nossebro. The contract was completed, but, partly because of some unforeseen technical difficulties, and partly because the company had to pay costs as a result of a forest fire caused by a Tipper Truck, the work was completed at a loss. Saabye & Lerche took the this on the chin and did not seek compensation.”

“Someone in Trollhattan noticed this and promised that he would seek to repay Saabye & Lerche for their positive attitude. His name was Major John Nystrom, one of the leaders of the large Swedish locomotive company, Nydquist & Holm, and he kept his word.”

“In 1917, Kampmann, Kierulff and I,” said Saxild, “had started our Company, and in the course of a few years we had very full order books, both at home in Denmark and in England, where we had formed a subsidiary called Saxild & Partners. I had no desire to stay in England for a time it was neceessary.”

“Nystrom,” Engineer Kayser added, “did not forget his 12-year-old promise to Saabye & Lerche, even though it was twelve years old,”

Engineer Saxild continued, lighting a cigarette. “Our work in England was in full swing, and I was visiting Copenhagen, where Kampmann and Kierulff had a lot to do, including some port facilities in Jutland. It was a Saturday afternoon in October 1926. We were sitting in the office in Vestergade and about to go home when the telephone rang. It was Engineer Saabye. He asked us to come to a meeting that afternoon. Major Nystrom and CEO Anderson from Nydquist & Holm and Attorney Holmgren from Gothenburg Handelsbank wanted to talk about two contracts for railway construction in Turkey. They had been offered the work but wanted us to undertake it.”

“It turns out that CEO Andersson had negotiated to sell 100 locomotives and 1500 freight wagons to the Turkish Government, but the Turks had made the sale conditional on the Swedish company building two railway lines, totaling about 1000 km, in the northern and southeastern part of the country.”

“Nydquist & Holm was not prepared to build the railways, but wanted to fulfil the delivery of rolling stock. Enquiries were made with major Swedish engineering companies without success. Major Nystrom remembered Saabye & Lerche. He called Engineer Saabye and offered him the work, adding that it was a very contract which could easily run into hundreds of millions. Saabye delayed his response for a meeting with the Swedes. They travelled on the ferry on the same day.”

“During the negotiations, it was quickly realized that a decision had to be taken quickly. The Turks had set a deadline eleven days hence. After a week, the engineer, Baron Otto Lerche, Engineer Per Kampman and Supreme Court Attorney Albert V. Jørgensen travelled to Ankara with the Swedes, and after some demanding negotiations, the contract was signed. A Consortiumcalled the “Swedish-Danish Group” (“Nohab”) was formed and a commitment was made to start work in the field on 1st June 1927 and to complete the work within 5 years. The cost was estimated at 200 million Danish Kroner. We had around 85 committed to the work and another 50 from other nations, predominantly Swiss. When the work was in full swing, 19000 men were employed. 119 major bridges were built, 3000 smaller ones, 104 tunnels and 65 stations.”

“Without going into detail about Turkey,” engineer Saxild said, “It formed the background to the company working in Iran. Work was completed on schedule and the Turks began to look for other work for the Company to undertake. It didn’t take long for a chance to emerge in neighbouring Iran.”

“You forgot to tell the story of Muchtar Bey …, ” the Legation Council said.

“Yes,” smiled Engineer Saxild, “Muchtar Bey was former Minister of Public Works in Turkey and, while working there, acted as a kind liaison officer between the Turkish Government and the Danish-Swedish Group. We had had an excellent collaboration, and Muchtar Bey had made many savings for us through his excellent negotiating skills. As a thank you we invited him for a trip to Denmark, and Engineer Kampmann was guide for him on the tours around Copenhagen and North Zealand’s attractions. They looked at museums, drank beer at Tuborg, visited Frederiksborg Castle, visited farming and cooperative dairies, were at Kronborg, and God knows where.”

“What made the biggest impression on the Turkish minister during his visit in Denmark, was not our industry or agriculture, not the Tivoli-garden, the cycling girls or other tourist shows, but that the Danish peasants dared to leave their milk churns by the road unguarded … This filled him with the greatest astonishment and admiration. He believed that there must be people who could be trusted who lived in Denmark!”

“How much Muchtar Bey talked about Danish milk churns when he returned to Turkey, I don’t know – but it may well be that the story was not without some significance,” said Saxild.

By this time it had grown late and many things were still to be discussed. A work plan needed draft into some sort of shape, aides needed to be selected. Introductory visits had to be prepared to the Ministry of Traffic as well as to see top Police officers, who had to issue Travel and Photography licenses, and many other things had to be discussed. The story of how the Iranian Adventure began had to wait for another day.

Chapter 7: The Railway Must be Built in Six Years – The headquarters of the Kampsax Consortium were on Avenue Hechmat-ed-Dowleh in Tehran – a former Prime Minister’s Residence, set in the middle of a beautiful garden. Behind the large goldfish pond you can glimpse a high wall which protects the neighbor’s park from curious glances. The neighbor was none other than Reza Shah, the ruler of Iran.

It has been necessary, on three occasions, to extend the building after Nordic engineers took it over in 1933. The large two-storey building now houses over 160 Engineers, Technicians and Office People, 45 of whom are Scandinavians and the rest Swiss, Armenians and Iranians.

We were guided around the building to meet the leaders of the many departments. The basement floor contained a Printing Department, a Photographic Studio and a very large Material Testing Laboratory, where physical and chemical analysis of Building Materials were performed from all the major construction work around the country. We were told that the head office had its own mail connections to each employee at work on the line. Even the most remote workplace received mail and supplies twice a week.

“But it’s not always everyday and routine requests that come from comrades in the field,” said the head of the purchasing, V. Simonsen. “We have arranged for the different categories of requisitions to be printed on vouchers of different colours. Everything that is for private consumption, for example, must be written on red vouchers. On one occasion,a red voucher came from an Engineer on the line asking for engagement rings to be purchased. The engineer in question lived in a very lonely place, so it was quite natural that the requisition aroused some curiosity in the office. We cautiously undertook investigations and discovered that it was an Armenian Beauty in a small village who had captivated the young Dane’s heart. We did not doubt that he had proper intentions, and that he had decided that the Covenant should be sealed with engagement rings. The Chief Engineer for section in question decided to talk seriously to the young Engineer on his next inspection tour – but fortunately, the engagement had already gone awry by the time he got there.”

“Another time we had a magnificent tiger skin sent in from one of our Engineers up on the Northern Line,” Simonsen continued, “with a request to send it for tanning. We did that, and a few weeks later we sent a wagon down to the tanner to pick up the fur. When the wagon came back to the office, I nearly had a stroke – the tiger was stuffed! And not only that, but the good tanner had done it in a way that revealed that he had never seen a picture of a tiger, let alone a living specimen of the breed. His head was down between his forelegs, his back swaying like an old donkey, and – best of all – his tail was rigid in the air like a pet cat. We had to open the beast up, take out the hay, remove the stick in the tail – and send the fur back to the tanner!”

“Finally, let me tell you what happened when we got an order from an Engineer in Qum for a 10 barrels of Igas kits – these are something you use to put in tiles. It was difficult to obtain, but in the end the Iranians I had put on the job succeeded in procuring the 10 barrels which were then sent to Qum. When our Engineer in Qum opened the barrels, they contained resin in place of the kits. However, the engineer was not slow on the uptake, he immediately sent us a slightly ironic letter, accompanied by a red voucher for 100 Violins …”

A total of around 300 men were employed within the Consortium’s own technical and administrative departments at the head office and on the line, but the workers employed by the Contractors in the Construction work and thus, indirectly, under Kampsax’s control, amounted to between 45 and 55,000 men.

Of course, with such a large workforce, accidents could not be avoided completely and significant health problems arose. Therefore, 2% of the Railway Construction costs was reserved for the administration of a “Sanitation Service” run by an Iranian Consultant. 500 men were employed within this Organization as doctors, nurses and ambulance drivers, and each of the 50 lots – i.e., sections of 12 to 17 km in length – into which the project was divided had its own small hospital, In addition, the Consortium built three large hospitals.

We went with Chief Engineer Blach on a visit to the Ministry of Transport, where great interest had been shown in Kampsax’ plan for a documentary film about the buildign of the railway. The Minister had submitted the idea to the Shah and obtained his Majesty’s sanction.

“The head of the department agreed by phone to see us at 11.00am,” Chief Engineer as we entered his office, but he sat down and let us chat for a little while.

We asked him to tell us more than we heard the previous evening. We asked, “How did this Iranian Adventure really begin?”

“I can probably tell you a little more,” Engineer Blach smiled and pressed a button. “Saeta Khaveh,” he said to the Iranian worker who came in. A little later, he returned with three Cups of fragrant, black “Turkish” Coffee with lots of grounds in the bottom.

“I was in Cairo when things started here in Iran. My work in Turkey was finished and I was in the process of setting up a contract in Egypt.

It was during March 1933. I was called by Engineer Kampmann from the Copenhagen office. I’ll never forget that conversation – it’s almost as if it was yesterday that I had it. Remember, I had just finished my work on the Turkish Northern Line from the Black Sea to the south in Anatolia, and although Icould barely breathe because of the temperature, I still missed the comrades and the joy that struggling together towards a common goal can provide.

“We are submitting a bid for work on the Trans-Iranian Railway,” Kampmann said on the telephone. “It is an even more demanding job than in Turkey, do you want to join us again? You have 24 hours to think about it and I will call again. If you want the job, you need to be in Tehran by Sunday!”

It was a Tuesday and time was short. I realized that if I had to complete my obligations in Cairo, there was no time to waste. And besides, there was no shadow of doubt in my mind that I wanted to be there again. So, when we talked, I said yes and immediately proceeded to dispose of my house and pack my suitcases. The day after I flew to Baghdad and from there went by car to Tehran. It was a distance of 1000 km, but I kept my appointment and was in Tehran on the Sunday evening.

At that time, Director Kayser was already in Tehran. He had worked as a Chief Engineer on the Northern Line in Turkey, and on an Inspection trip in Anatolia he had received a telegram, in which the Copenhagen headquarters asked him to return immediately to Denmark, where he, after being given instructions, would travel through Russia to Tehran. He did not take long to think either.

“How did we get the job here in Iran?” continued Engineer Blach, “I just need to sketch out a few details for you.”

“Reza Kahn took power in Iran in 1921 and was declared Shah in 1926, but already in 1922 he had established a monopoly on tea and sugar, the tax on which was allocated to a fund the construction of railways. He believed that the construction of such an important railway as the Trans-Iranian, which, with at 1400 km, would connect the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf and would undoubtedly have great strategic and economic significance, should not be financed by external loans; but should be entirely under the control of the country.”

“One quickly discovers here that tea and sugar are important to every self-respecting Persian. He drinks tea several times a day and will usually have 5 or 6 lumps of sugar in each glass. It is no wonder, that funding arrived quickly. By 1927, the funds were sufficiently large to allow the Shah to begin work, and he allied himself with an international syndicate of railway contractors who embarked on the design and construction of the railway. For the time being work started on the flat stretches near the Caspian Sea in the North and the Persian Gulf in the South and headed towards the interior of the Country.”

“That was, as I said, in 1927 – at the same time as we started work in Turkey. After two years work on the Trans-Iranian Railway, it had reached around two hundred kilometres into the country from each end, but then suddenly progress ceased. Partly because of the terrain, partly because of the climate – especially in the southern part of it – foreign engineers began to struggle with the work and the Shah lost confidence in them … and that was crucial. Their contract was cancelled and the Iranian government began trying to carry on the work itself.”

“To the north, it was one of our former employees from Turkey, the Swedish Engineer Lindahl, who led the work, and to the South, an American called Caroll. At the centre, in Tehran, sat an old Swiss professor who was a railway specialist but did not possess the leadership skills needed to direct such a large enterprise. The Northern Line was built according to Swedish Principles, in the South, work was in line with American ideas, while the management in Tehran tried in vain to get both parties to use the Swiss construction standards. The backbone needed to push this through was totally lacking, and so it did not happen.“

“From Turkey, the Swedish-Danish Group had, of course, kept abreast of developments in neighbouring countries, and in the autumn of 1932 the management sent an observer to Tehran. He brought an extremely flattering letter of recommendation about the work of the Consortium in Turkey from the Foreign Minister, Kemal Attaturk to his colleague in Tehran, and it did not take long before the Iranian Government wanted to commence negotiation with a representative of the Consortium.”

So it was that Kayser came down here with directives from Kampsax’s head office in Copenhagen, and on March 22, 1933, Director Saxild arrived to lead the final negotiations. On April 22, the contract was signed and work was immediately underway. Many of the Employees from Turkey were scattered across the globe, but managed to get most of them back together, while many new ones were hired, both from the Nordic countries and other places.

“Don’t you think it was the biggest contract any Danish engineer has put his name to?” I interjected.

“Yes,” replied Engineer Blach, “you can safely assume that. initially the contract was worth around 550 Million Danish Kroner – later when the decisions was taken to separate the work into different ‘lots’, the revised price was agreed as 600 Million. What was dangerous about the Contract were the deadlines set by the Shah. He wanted the railway completed – and quickly completed – and so he had put a condition – his sine-qua-non – into the contract: the railway must be completed in six years. As a further stipulation, the construction time for the Northern Line from the Caspian Sea to Tehran – or rather, from the city of Shahi, where Lindahl’s line had reached – was set for four years. As you may know, the North Line was completed in May 1937, two months before the date agreed.”

“How in the world can one calculate such a thing, it must then be an equation with several unknowns?” I asked.

“We had the experience of Turkey, but still a good portion of optimism was required to deal with the conditions … but we had that,” Blach smiled. “The greatest difficulty was that in Iran there were insufficient capable and strong entrepreneurial firms able to undertake the work. Through the good-will created in Turkey, the Consortium had good connections in various countries. Kampsax itself would not be building the line – the Consortium is the Government’s advisory and authorized engineers and acts as a kind of government department. It would offer the individual parts of the work to others and organise international tendering. Kampsax’ main task was to determine the route of the railway, carry out all technical studies and projections and then, on behalf of the Government, supervise the performance of the work. So, we manage the sums allocated to the railway, make all payments and report to the Ministry.”

“The advantage of this scheme is that we both have the same authority as the Ministry but have maintained our full independence as a private enterprise. We have no intricate and bureaucratic business processes and so can make decisions and act quickly wherever possible, I am 100% sure that otherwise we would not be able to accomplish such a comprehensive task within the deadlines that we have committed ourselves to.”

I can tell you that in 1933, before the work started, Engineer Saxild and I devised a detailed program for the work. We are building the tracks from both ends, and according to the plan, the rails from the north are to met the rails from the South in August 1938 at a site located 290 km north of Salehabad (a town about 250km from the Persian Gulf) We will see if we can achieve this!”

“When I came here from Cairo, the contract was not yet signed, but the government had so much confidence in us. The signing went well and I was immediately sent down to Salehabad for a talk with American Chief Engineer Caroll and the other Americans down there.

It all started quite oddly, I had met with the Minister of Transport, Ali Mansour, and was now discussing some details with his Head of Department, who was Armenian. We agreed that I should travel to Salehabad as soon as possible.

“We must get you a vehicle,” said the head of the department, and sent a servant with an order. A little while later, the servant returned with a rather frail taxi driver, whom he had picked up on the street, and now a costly scene began to unfold. For a long time, the Head of Department and the driver bartered over the price of the, around 700km, trip from Tehran to Salehabad. One moaned over the price, the other over the offer, but eventually the gentlemen agreed and I left. Before I walked out the door, the head of the department told me that if I needed money down there, I could just telegraph to him.

“When I had been in Salehabad for a few days, I became aware that those winding-up the US Office needed to remove equipment, so I telegraphed for some money to keep the work going. The following day an amount came, around 500,000 Danish Kroner, or 1.5 million Persian Rials! That is what you can call confidence! …”

“People might see that as exciting, but for me it was the challenge of seeing a railway built in 6 years that was exciting,” continued Engineer Blach. “But it wasn’t until later that I got to know the South Line terrain properly, that was once we did the first Reconnaissance and had to walk or ride the entire route. The Canyon District areas in Luristan could not be traversed at all at that time. There was neither road nor path, and the service roads that now exist, we were only finished a few years late. Anyway, ” he said, “you will soon get the opportunity to to see what it looks like!”

“The first thing we did when the Contract was confirmed was to take over the work underway in the north and south, and it wasn’t long before around six thousand men were at work. The next step was to determine the alignment of the remainder of the line – around 1000km. On the Iranian plateau, this task was not very complicated, but in two places the line would pass through such difficult terrain hardly ever encountered by railways elsewhere in the world. One place is on the Northern Line – the Elbruz mountain range. It extends in a west-easterly direction, parallel to the Caspian Sea coast. You can’t get around it, you have to go through it. The ascent from the flat coastal country up to the high mountain pass (over 2000m above sea-level) is so steep that the route has to chosen very carefully – but you must go to the Northern Line with Karl Olsen one of these days, then he will show you what I mean. I cannot describe it adequately.

But the other place – down on the South Line – I can describe. But here too, one must see it in order to form the right notion of how unlikely it was that we would plot a route through the terrain. Come here and see.”

We went to the big map on the wall. Engineer Blach’s eyes glowed as he followed the meandering route of the line with his finger. You could feel that every point on this stretch brought amazing experiences, but at the same time fierce battles against nature, a battle where man and machine eventually won through.

The route from the Iranian plateau into the wild mountains of Luristan Province, follows a river, Ab-in-Diz, a rippling stream that for some distance winds through a series of canyons, deep mountain gorges with almost vertical cliff walls on both sides. Do-Rud and Shabazan, located here, are 150 km apart. There are no less than 200 tunnels with a total length of over 60 km on this 150km stretch. The terrain is harsh.

“I was the leader,” Blach continued, “of the first Reconnaissance Expedition on the South Line, and it took us 24 days to cover the 150km. There was neither road nor path, often we had to crawl, even on mountain sides, where otherwise only goats could move. Often we had to make great detours, in one place the terrain was so difficult that it took us 2 days to make 6km.”

“It was no ordinary walk – it was july and the thermometer reach 52°C in the shade and we were sweating so much that the water ran off us. Of course, there were limitations over how much water we could carry, but there were absolutely no limits to what we could drink when we found a source of fresh water. Each person needed 12-13 litres of water a day to counteract the body’s tremendous loss of moisture.

“We often had to swim across the Ab-i-Diz River, or if the current was too strong, we’d haul ourselves across on a rope which a native bearer would have fixed to the far bank. The natives had their own method when it came to crossing the river. They brought a sewn goatskin into which they breathed air, and then they sat down on the dead goat and paddled across the river with the luggage on their heads. As a rule, the current took them they would end up several hundred yards down the river – but they always managed to get across. There was one of these bearers that we always followed with a special interest when paddling across the river. It was he who carried our meager stock of whiskey … you must not think life was hard for us, on the contrary, while the sun was in the sky, there was no talk of having to stir spirits – if you started it, you would quickly be dismissed – but at night, when we got to our tents dead tired and had something to eat, then we always had to have a drink before we went through the day’s observations and measurements.”

“Did you not face unpleasantness from wild animals or hostile natives?” I asked.

“Well,only once was it close to going wrong. But it was not the natives who were the problem. We were crossing a fairly narrow mountain canyon. I arrived a little ahead of the others. Suddenly, I see something rising from shrub a close of me. It was an unusually large male wild boar with some mighty fangs. For a couple of seconds it stared at me, then it charged. I only had a small 6mm Winchester rifle with me – and trying to stop a tormented Wild boar with it would be the same as trying to stop a locomotive with a bow and arrow. I stood, nailed to the spot- there were high cliffs on both sides – the situation looked pretty hopeless. Of course I cried out to our rifle men, but they were 50 yards away, and I stood between them and the boar.”

“Suddenly a gun went off, the boar stumbled, got up again, and then, 3 or 4 metres it collapsed, kicked a bit and then lay still. It was one of the security men, … he, no doubt had saved my life.”

“I also remember one particular evening when the reconnaissance party stopped by the Ab-i-Diz River to camp. A little distance from the camp-site, the river broke a narrow gap, an almost vertical cliff that went down to the water’s edge. While the bearers were raising the tents, the Swedish engineer Hacklin and I went to the cliff to see what was beyond. As we approached, we heard a noise a little ahead. It sounded like it came from the other side of the river, but it was only about a metre wide at this point.

“I readied my rifle, which, after the story with the wild boar, rarely left me, and carefully listened. As we came around the protruding cliff, we saw a strange sight on the other bank. With his back against the cliff wall, a large bear stood and struck out violently with its forepaws at two leopards attacking it from both sides. What their problems was, we could not see, and I did not feel the need to get involved with my rifle – and besides, it wasn’t long before the animals disappeared.”

“Are there many snakes here in Iran?” I asked.

“No,” Engineer Blach replied, ” At least, I have not seen very many and most of them were quite small. Scorpions on the other hand, there are many of them. I once had an unpleasant experience with one. I had put my sun helmet off for a moment in order to rest, and when we went on, I put it on as usual. I must have been half an hour later when I noticed something creeping in my hair. When I took off my helmet, a big scorpion fell out … I was very lucky. There are many who have become seriously ill after being stabbed by one of these beasts. Always remember to shake your boots in the morning when you are now out in the field, and for a safety’s sake also look inside your helmet!”

“What happened after this first survey?” I asked.

“We sent out a new survey team to make maps which made a survey to create rough tachymeter maps, which form the basis for more detailed mapping of the terrain. From the maps/plans the final route of the line is laid out in the field. Then we had to build a service … as close to the route of the line as possible. For instance, between Shabazan and Do-Rud, this work took over two years. Only after this, could compressors and drilling equipment be brought to the locations where the tunnels were to be drilled. In many places … the service road had to be blasted into vertical cliff walls and interim bridges had to be built before the construction of the railway itself could begin.

But even though at times progress seemed slow, actually work is raging ahead!. What you will probably discover as you follow the South Line, is that there are large stretches which are unfinished. The Contract period still has 18 months to run, we will be finished in the six years promised. All of us in Kampsax are dedicated to that goal. Most of the Contractors also take pride in meeting their obligations and deadlines – and if someone does not, well, they are removed and Kampsax undertkaes the work at the Contractor’s expense.”

“Has everything gone according to plan, or have any unforeseen events occurred that have delayed the work?” I asked.

“On the whole it has gone according to plan, but in some places we have been surprised, it can’t be denied. You will better understand these locations when you are on site. Remember to ask Karl Olsen to tell you about the Spring River at Abbasabad and the large landslides at the Miånkola – I should probably give Aage Jensen some tips from the South Line. For example, several times, a mountain slope has started to move when work begins.”

Engineer Blach looked at his watch and pressed a button.

“Now we must meet with the ministry,” he said, and told a servant who stepped in arrange the car to take us there.

Fifteen minutes later, we sat with Department Manager Methat in his large, bright office in the Ministry of Transport, and for a few minutes we exchanged news before we began to discuss ‘Le film du chemin de fer transiranien’ – The conversation took place in French, so I had to draw on my schoolbook French and tough it out. A servant came in with the obligatory glass of tea.

“Chai, Messieurs …”

Chapter 8: Three Gradient and Other Things – The brown, deserted landscape outside Tehran warmed as the sun penetrated the morning cold Behind us, the city disappeared in the gray-white dust cloud that followed our car. Looking towards Rey, you could still see the smoke column from the cement factory’s chimney, but soon it too was obliterated by the dust.

The transition from city to country is very sudden when you leave the capital in an easterly direction along the old caravan road towards Meshed (Mashhad). After the last low houses, surrounded by yellow, clay-clad walls, you are immediately out in completely undeveloped terrain.

Unlike other major cities, no migrant houses, no villas or colony gardens, no emerging industrial areas mark the transition. The bare, steep mountain slopes to the east of the city have not experienced Tehran’s expansion in the way that the fertile areas northwest of the city, where the summer towns of Shimran and Golhak are located in the slopes of the Elbruz Mountains.

The terrain became more hilly as we approached the mountain range itself. Without slowing our the pace, but with constant use of the car’s two-toned horn, Michel, Karl Olsen’s Armenian driver, drove around a slowly moving caravan of heavily loaded camels. We got a hard stare from the first Camel … With deep contempt, it looked at the alarming, … metal box pushing past – Why such haste, you foolish people? I have much further to go than you, all the way to Meshed (Mashhad), nine hundred miles to the East, I have to walk, before reaching My Goal – and see if I hurry? I might get there, insh ‘Allah …

The Chief Engineer turned to us with a cheerful look behind his horned glasses. “These camels are ridiculous animals. … Apparently, they look with great contempt on us humans, especially on those of us who are busy. An old Persian once told me that if you take the lead camel and place it further back in the caravan, it will refuse to move on, and soon after it will die of shame.” And we can believe in that story, as we watch them now walking in such a ‘grandiose’ manner as they are now …

The road gradients steepen and the road wanders and in sweeping curves and hairpin bends through the Elbruz Mountains. As we reached a tight curve with a deep abyss on one side and an almost vertical cliff wall on the other, Michel gave a grin and hit the brakes. The roadside along the abyss was marked with white stone, but two of them had been overturned, and tyre tracks continuing beyond the edge showed that an accident had occurred here. We jumped out of the car – and there, 50 metres down in the canyon, lay the remains of a large truck.

Michel went to a couple of road workers, who were repairing the road a little further ahead. When he came back, he explained that the accident only happened 4 hours previously. Probably, the driver fell asleep at the wheel (from fatigue or opium). His crushed body was taken to Tehran by a passing vehicle.

A few kilometres further on, where the road ran down a cliff-edge we passed a large memorial stone at the roadside.

“This was the scene of a terrible accident some years ago,” Karl Olsen said. “It was a dramatic event and the Shah was at the scene. … The Shah was on his way to his properties in the province of Mazanderån by the Caspian Sea. In front of the Shah’s car was a large vehicle with a Division of Soldiers from his bodyguard. As it drove down the steep hill, the brakes suddenly failed, and instead of reducing the speed by shifting to low gear or driving toward the mountainside, the driver jumped off to save his life. The result was that the vehicle fell into the ravine. All his passengers were killed. The Shah got out of his car, walked over to the driver and shot him on the spot with his revolver!”

The road began to turn in a northerly direction. The bright sunlight, which fell on the brown, deserted valley sides, disappeared for a few moments as we drove through a road tunnel. Another couple of serpentine twists in the road and suddenly, after rounding a protruding rock, the landscape opened up and a great panorama lay ahead of us. The road descended towards a beautiful valley with green fields and lush vegetation, through which a stream wandered. The Western Horizon was dominated by the mighty, snow-white cone of Demavend, which rose several thousand metres above the nearest peaks in the Elbruz chain. To the north, the brown landscape sloped up towards the Gaduk Pass, the highest point on the northern line of the Transiran Railway.

We looked at the clock and noted the time and position of the sun in a pocketbook. Several pages were already filled with notes on camera settings on the route and ideas for filming. For the time being, there was only talk of reconnaissance, as we had not yet obtained photography permit from the police.

We had not seen anything of the Railway yet. It ran in a large arc from Tehran to the southeast before turning north, and we were to encounter it first at the town of Firuzkuh on the other side of the valley we were now in. At the town, the railway crosses the highway from Tehran and the road divided in two – one route heading east to holy city of Meshed (Mashhad) near the Afghan border, the other following the railway across the pass at Gaduk and through the valley of the River Talar to Shahi and on to the Caspian Sea.

At Gaduk, we sat talking on the platform outside a small, cement-grey station building. A sign with Persian letters told those who could read it that this was Gaduk, 218 km from Tehran and about the same distance from Bandar Shah on the Caspian Sea. But not a word that we were at the highest point of the North Line – 2100 metres above sea level.

“Why are engineers always so damn businesslike,” Axel said. “It would have been quite good for the travelers to know that they now found themselves at the highest point of the Northern Line.”

“I must correct you now,” replied Karl Olsen. “Kampsax did not have the responsibility for the station signs. These have been set up by the Iranian Railways themselves. However, it would be incorrect to designate the Station here as the Northern Line’s highest point. It is inside the mountain ahead. The tunnel, which starts just north of the Station, is 2880 m long, From the far end, the profile of the tunnel is not a straight line – at some point the ascent is interrupted, and the line begins to descend towards the station here and then further down onto the high plateau. The highest point is 1300 m from the tunnel opening. You can see the opening ahead.”

We followed his gaze. A few hundred metres from the platform where we sat, the shiny rails disappeared into a black hole in the mountain – the Gaduk tunnel. …

The north line was not yet open for regular traffic, but when we passed Firuzkuh, the stationmaster had told us that a postal train was on the way from the north and that we would be able to meet it in Gaduk if we rushed.

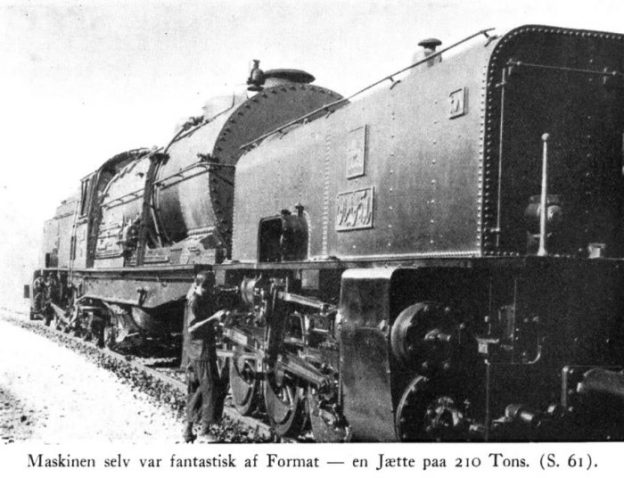

Michel floored the accelerator, and we had probably sat for a quarter-of-an-hour on the platform before the sound of a train could be heard from the Tunnel. A large, yellow spotlight appeared inside the dark hole before immediately fading into the shining sunlight as the hissing monster of a locomotive pushed out of the tunnel opening. Slowly, the train pulled forward and stopped in front of the small station building. It consisted of a long row of goods wagons, a mail van and one passenger coach carrying with Iranian Technicians and railway workers. The locomotive itself was amazing. Its format and construction far removed from the usual perception of a locomotive. Beyer & Peacock, of Manchester could be seen written on the boiler. A giant Beyer-Garratt Locomotive which weighed-in at 210 tons.“Yes, it’s a British locomotive,” said Karl Olsen, a so-called ‘Garratt’, specifically designed for railways in difficult mountain terrain with tight curves and steep gradients. As you can see, it consists of three parts, the boiler in the middle and two steam engines – the one in front carries a large water tank, the other includes the tender, which contains fuel for the oil-fired boiler. The three parts of the locomotive are interconnected in such a way that they can rotate in relation to each other. An ordinary, large locomotive with a similar traction would be far too rigid to handle the tight curves on the line on the far side of the Gaduk pass. As we drive north in a little while, I’ll show you one of the most remarkable railway routes in the entire world.”

The Garratt locomotive was disconnected from the train, the two the whistle was blown, and slowly the beast moved off on its twenty-eight wheels into a siding, where it stood quietly and chattered to itself – a giant of two hundred and ten tons relaxing after the effort it had made. A large locomotive of a more normal appearance was now attached to the train. The brass letters on the cylinders indicated that it was built by Nydquist aand Holm from Trollhåttan, Sweden. A little later, the train set off south towards Tehran, and we went out and woke Michel, who was sleeping at the wheel of our car.

We had probably driven a kilometre north of the station when Karl Olsen turned towards us and pointed down towards the floor of the car.

“We are now crossing the track,” he said, “The tunnel is just down below.”

The climb in the Elbruz Mountains was over. After a few minutes’ drive, the road cut through a narrow mountain pass and then began to descend towards the Talår valley. A little further ahead, the road and the railway again intersected, just off the northern end of the long Gaduk Tunnel. But now it was the road that was lower. We drove under the track through one arch of a viaduct. As we drove on down the valley we could see that the level difference between the railway and the road became bigger and bigger. Both road and rail were descending from the 2000 metre high Gaduk Pass as quickly as possible – the road was winning the race

The chief engineer suddenly ordered Michel to stop the car and decreed that now we had to “go to the fields for a quick look”. It was a long and rather strenuous climb, after which we sat and caught our breath on the western slopes of the Talar valley. On the horizon in the East, the peaks and ridges of the Elbruz Mountains spread out. Across from us, but a little further south, a wide valley intersected with the Talar Valley. We could see the railway across the valley on a long viaduct and then it disappeared into the mountain opposite. Another line emerged from the valley floor below the viaduct and continued perpendicular to this into the same mountain a few hundred meters from the first tunnel opening. It looked pretty mysterious. Further north, three railway lines ran above and below each other along the same hillside. If this was the same railway then it looked like a roller-coaster of gigantic dimensions.

Presumably we looked rather disoriented and Karl Olsen smiled when he saw our inquiring eyes. He then pulled out a large card from his pocket.

“Here is a Plan of the Line from Shahi to Firuzkuh,” he said. “Now try to forget that we have come via Gaduk today – it is all easier to understand if we start from the north, up from the Caspian Sea. The ascent from the lowland forest districts and rice fields in Mazanderån up to Gaduk is far too steep for a regular railway to manage it in a straight line. because of the distance involved it would both be expensive and very impractical to construct a rack railway here, so there was nothing else to do but to let the line make a series of fantastic turns and at the same time climb into the hills at gradients as steep as 2.8% (28m per km), which is close to the limit of the maximum that a railway can achieve. Now see how it looks on the map. From Shahi to Gaduk is 82km but the height difference between the two places is over 2000 m, and this means that the length of the railway needs to be as much as 115 km. Over the first fifty kilometres road and railway follow each other and are almost equal in length, but then the track can no longer cope with the climb and starts to ‘spoon out’.”

Karl Olsen pointed to the map. “Here at Lot 5, the difficulties begin. As you know, we divide the work on the line into ‘lots’ or sections – there are ten from Shahi to Gaduk – and on the map you can see what curves the railway must describe to gain enough height. Several places on this stretch include a three-story railway. We let the line follow tight curves in tunnel maintaining a steep gradient. Then the line runs in the opposite direction before it turns again and runs towards it goal. You can see on the mountain over there what this looks like. The train comes from the north on the lower ramp, turns inside the mountain and returns … along the middle ramp. 4-5 kilometres further north, the train runs through a turning tunnel and then comes out onto the upper level, where it continues south again. That way, you win a couple of hundred feet in height. What you see in the Churab Valley over there is another system. The railway on the Viaduct and the line running perpendicularly to it are parts of the upper circuit of a figure eight. The lower part of the figure eight lies inside the mountain to the south of the viaduct. To understand it best you have to ride the line probably in a work vehicle and with a map in hand.”Axel and I exchanged a look. “Cartoons,” we mouthed to each other.

Describing labyrinth in a film would be very difficult. Normal images alone would not be enough, but combined with Cartoons it might be possible.

“Going on, the Churab Valley caused us quite a lot of trouble,” Karl Olsen continued. “It was difficult to find the simplest and most economical solution. Several ideas were formed and followed up but none of them were satisfactory. It was the Swede Hacklin, the Iranian State Engineer for the track, who found the solution. At a meeting where the choice was to be made between the proposals, Hacklin came in quite quietly, swept aside all the many plans and drawings and scratched the figure eight onto a piece of paper. When he was done, he quietly listened again and went home to sleep. The other people in attendance reluctantly accepted that his solution was right.”

“If you want a few figures about the route through the Talar Valley, I can tell you that the distance along the road from Lot 5’s northern boundary to Gaduk Station is 29 km, the height difference between the two points is about 1400 m and the length of the railway is not less than 61 km. On that stretch alone we had to build 50 Tunnels and 36 larger bridges.”

We travelled on North passed the three-tier tracks at Dogal. The lower track runs roughly at the same level as the road and the upper track a few hundred metres up the mountainside. Up close, we could see how difficult it must have been to build these three levels along the mountain. Viaducts, galleries, tunnels and retaining walls all mutually overcoming the mountain which is furrowed furrowed from the upper tier to the bottom of the valley and scarred by huge slides of excavated material. …A few kilometers further on, the Valley narrowed and formed a gorge. On a rock ledge over 100m above the road one could glimpse the ruins of an old fort whose strategic location over the caravan road through the pass was well-chosen. The builder of the castle, however, could not have dreamed that his castle would have a railway as its immediate neighbour!

Further on beyond the pass, the landscape changed character. The valley became wider, and the high mountains on the west turned into soft, rolling, hills. On the eastern side, the mountains were almost steeper than before, and just off the small village of Abbasabad, whose clay-clad huts spread between the road and the almost dried-up river valley, the mountainside was intersected by a deep gorge.

“The Vresk Valley,” Karl Olsen said, “and we are honestly a bit proud of the bridge over it.”

We looked up. The narrow, V-shaped mountain gorge was held together at the top by a slender bridge structure whose elegant arch stood shining bright in the low afternoon sun – a beautiful revelation of modern engineering. We asked Karl Olsen to tell us a little about the Bridge’s Data.

“… The bridge is 120 metres above the valley floor, and its length is 86 m. Like most of the bridges up here, it is made up of cast cement blocks – it gives greater elasticity than reinforced concrete, something that has significance in a terrain like this, where earthquakes occur quite frequently. On 29th July 1934, we had a terrible experience while working here in the Vresk Gorge. The line curves away from Abbasabad Station and enters a turning tunnel that ends just before the ravine, in the bottom of which runs a small innocent looking stream. when planning the project, we had expected a lower bridge that would take the railway across the creek to a tunnel on the other side, through which the line would continue along a long detour to the north and through a new turning tunnel to climb the 120 m up to the Vresk bridge.”“While we were working on the little bridge down at the bottom of the gorge, there was a prolonged period of rain which caused some flooding, but our calculations still held sway, and no one in the village was worried. In the afternoon of 29th July, a violent cloudburst occurred and in the evening, disaster happened. A flood of water came tumbling through the gorge with tremendous force, a debilitating mass of water, soil, and stone that took everything with it, a swelling so massive that stones of up to half a cubic meter were bobbing along on the surface of the water. Everything that was in the way of this wave was swept away, both the bridgework and part of the village. Unfortunately many lives were lost during the disaster. This little creek … which, in living memory had caused no problems but just trickled down into the Talar Valley in a culvert under the road and with many village houses on its banks, even a large teahouse … caused catastrophic disaster. The river of mud came roaring down the bed of the small creek. Two of our Engineers, the Norwegian Haugen and the Dane Weitemeyer, lived in Kampsax’s House on the western slope of the vealley. They heard a noise like roiling thunder from the Vresk gorge, followed by a crackling, roaring sound and screams from many people down in the village. They rushed there, and it was a terrible sight that met them. The road was torn down, and the village split into two parts. A broad strip, where everything was ravaged, was drawn across the small community. The large teahouse, which was always full of guests at this time, had disappeared, and many other houses were also gone. The flood had unimaginable power – large boulders were torn down through the village and thrown into the Talår River, which was also swollen and several places over-topped its banks. The next day, many mutilated corpses were fished out of the river up to more than 20 km further north.”

“The disaster meant, of course, that the line had to be crossed over the Vresk gorge in another way, and we now changed the project so that the railway went through the tunnel and under the canyon. Over that tunnel section, we built a very broad and very solid channel which took the creek over the railway instead of under it. This prevent damage should the incident be repeated. And it did. Despite the fact that even the oldest residents of Abbasabad had never experienced anything like it, the event was repeated just three years later. ….. Sadly just 6 months after the first flood Abbasabad experienced another natural disaster, a violent earthquake, which occurred at night. Engineer Weitemeyer later said that there had been a strange, eerie mood all day in the village. The dogs were moaning, and the old Mullahs whispered that there was “something in the air.” Engineer Haugen and he had obviously not believed in the old men’s accident alerts – but on the other hand it really did not surprise them when the earthquake came. Some damage occurred, Kampsax’s large hospital building which sat above the village was badly damaged, but in comparison with the flood, the city escaped relatively unscathed.”

“Indirectly, this earthquake, nearly cost Engineer Weitemeyer his life. Every year, the Persians celebrate a religious celebration in memory of a Muhammadan martyr, Hussein. According to tradition, it takes the form of a kind of passionate game with a procession in which the participants – and often the spectators – experience religious ecstasy. In the past, it was common for them to whip or cut themselves. …. The mullahs in Abbasabad had done what they could to excite the people before the celebration, including telling them that the earthquake was an outpouring of Allah’s wrath against these strangers – Faranghi – who went around drilling holes in the mountains to no benefit to the world. As the procession, followed by a mighty crowd of spectators, passed through the town, Weitemeyer was so careless as to try to photograph it. Although he was some distance form the festivities, it was noticed, and a moment later, he was surrounded by hundreds of excited people. The camara was torn from him, and the crowd began to throw stones at him. Bleeding from major wounds to his head, Weitemeyer became unconscious. He was bravely dragged into the police station by Iranian police officers and kept there for a while. Taking him to hospital was not possible because of the risk of further attack from the crowd. He had to stay at the Police Station for several hours, and only when the native workers, who had at first threatened to storm the Station, withdrew, could he be carried to the Hospital. Fortunately, he recovered from the wounds, and the workers soon forgot their anger.”

“Well, now we’d better greet Zimbelius,” Karl Olsen ended, and gave Michel the order to drive up to the Kampsax House.

We drove through the village and up a side road on the western slope. The only houses in Abbasabad itself that did not seem ready to collapse simply at the thought of a flood, were the railway station and the police station. Many of the cottages stood empty and dilapidated – it was evident that while Abbasabad had had a hectic flowering while the railway was under construction, it now seemed ready to slumber again or possibly develop into a decent little station town.

Zimbelius turned out to be a young Austrian engineer in Kampsax’s service who, together with a Danish engineer, Kildehøj, oversaw some additional track installations. They lived in a small stone house a short way up the mountainside with a magnificent view of the Abbasabad Valley and over to the Vresk Bridge which hovered over the deep gorge in the mountainside opposite. The site had previously been the headquarters for the work on the Northern Line, and some distance down the slope lay Kampsax’s Hospital and some Buildings belonging to the Contractors. The office building itself was now transformed into a rest-house, and this is where we would spend the night.

An unusually skeletal Persian Waiter with speckled henna-colored hair came out to the car to take our suitcases.

“Salå-åm Aleikum,” he said and bowed deeply.

“Salå-åm, Ali,” replied Karl Olsen and turned to Zimbelius, who came out of the house, followed by his young wife with a little daughter on his arm. When I greeted Mrs. Zimbelius, who was Austrian just like her husband, she suddenly asked – in perfect Danish – how Mrs. Bolette Lund in Hellerup felt.

I think I looked pretty confused. I think I looked pretty confused. Admittedly, my lovely old hostess was known as an excellent French teacher, but that her reputation should have reached all the way to Abbasabad sounded a bit strange.

“I can understand that you are astonished,” Mrs. Zimbelius smiled, “but the explanation is straightforward. I lived as a Viennese child with Professor Ejnar Nielsen in Ahlmann’s Alle, where Mrs. Lund was often a guest. She often told me about the students who lived with her and about the crazy things they did, and I think your name appeared quite often in her stories.”

It was a cheerful evening in the young engineer’s home, and it was quite a time before Karl Olsen told Ali to turn on his lamp and escort us over to the little rest-house.

That the first day out on the line left us buzzing. …. The next day our trip continued north. From Abbasabad, which is at about 1500m above sea level, the road descended steeply towards the Lowlands. … Eventually, the terrain becomes so smooth that railway road are easy. The tall, sparsely wooded mountains, now behind us, the countryside was friendly and smiling, with forested hills on either side of the wide river valley. We approached Iran’s dining room, the fruit-barren northern part of Mazanderån Province. One rice field after another appeared. In most of the fields, the rice was harvested and stacked is small golden ‘nests’, Open huts storing rice were surrounded by posts and barbed-wire fences to guard against wild pigs. In several places , the guards were children, whose only weapon was a kind of rubbish or a metal plate on which they hammered to frighten the large animals.

“This is one of Iran’s worst Malaria districts we are going through right now,” Karl Olsen said, “And the mortality among the workers when we built the track here was, to begin with, incredibly high. Engineer Wright, who was the top manager of all the construction work on the North Line, and Dr. Torfeh, the Iranian Chief of the the ‘Service Sanitaire’, organized a huge battle against the Malaria. The entire workforce was handed quinine but they would not take it. Large quantities of quinine suddenly entered the market in Tehran – the workforce preferred to sell it. Then they tried something new. Every day, all the workers were lined up, and health workers went along the rows and put quinine pills in their mouths.”

“When it was discovered that several of the workers pretended to swallow the pills and then spat them out in the alley, they were served the quinine in dissolved form with the order to swallow it immediately and then open his mouth again- to be sure that this had happened. ……”

“The quinine mitigated the worst effects of the malaria, but the disease still ravaged terribly. … The Hundreds of swampy rice fields in the area were excellent hatching grounds for the malaria mosquitoes. Engineer Wright prepared a detailed Report to the Ministry with radical proposals to change things. The case was presented in the highest level, and the Shah was not long in making his decision – all rice cultivation was immediately banned in the districts through which the railway ran. The farmers who cultivated the fields there had to move temporarily to other places or take up work on the railway, and shortly after the fields had dried up, the cases of malaria were reduced considerably. It was a tough but effective decision,” concluded Karl Olsen.

Miånkola – for the stranger, a poetic-sounding name for a small village about 25 km south of Shahi, the city where Kampsax’s work on the Northern Line had begun. For the more dedicated and especially for the engineers who worked on this section during the first difficult year, the name Miånkola will always mean a series of dramatic events that were developing into a serious crisis situation during the construction of the Trans-Iranian Railway.

We stopped at a small cluster of houses on the right bank of the Talar River. It was almost impossible to understand that it was the same river that we had followed all the way up from the Gaduk Pass. It wasn’t just because the river was broader down here in the lowlands, but the landscape it flowed through here looked as if it was in a completely different part of the world. ……

A dense, subtropical forest growth, rich in vines, mistletoe and other spiny plants, spread in most places right down to the river. …

Through the dense scrub we could glimpse the railway on the other side of the river, a little up the slope. The line ran through a cutting and in a couple of places passed through a tunnel that cut into the slope over a longer stretch.

“The difficulties here at Miånkola were something we inherited from the people who had started the work up here,” Karl Olsen said. “I was Head of the Engineering (or the Technical Bureau, as we call it) in Tehran and had more to do with the theoretical side of the work. The one who could best tell you what happened here is Engineer Wright. What he doesn’t know about Miånkola is not worth knowing …”

What more Karl Olsen told us about the battles the engineers had with the terrain conditions at Miånkola, I have forgotten. I can remember that we drove on to Shahi and that same evening back to Abbasabad.

Not until several years later, when writing this report, did I visit Engineer Wright in Copenhagen and ask him to tell me about the events in Miånkola.

“I came to Tehran in July 1933, as Director of the Kampsax Consortium,” Engineer Wright began, “and was assigned the Leadership of the Work on the Northern Line with Chief Engineer Park as my closest Employee. The Foreign Consortium, which began construction of the track in 1927, built the line from Bandar Shah on the Caspian Sea to Shahi. … The government then tried to build on its own, and up here it was the Swede Lindahl who was given the leadership. The work on the excavations for the track was then sub-contracted to Tricheron’s, smaller Contractors who each had a stretch of the line, and it soon became clear that the task at Miånkola was much more difficult than expected and caused difficulties which the sub-contractor could not overcome. It was a very demanding job. The slope where the railway was to go was highly water-bearing, and as digging commenced, the ground lost stability There was imminent danger of a landslip.”

“The route of line was not chosen by us and could not now be changed. … As you know, we had committed to finishing the North Line in four years, and the Shah followed the work with the greatest interest. He still kept a close eye on progress, and regularly drove along the line, at least twice a year, so that he could see progress with his own eyes.”

“In November 1933,” Engineer Wright continues, “the Shah came to Miånkola, where I had the opportunity – with the Minister of War as an interpreter – to explain to him the particular difficulties we had and the precautions we had taken to overcome them. The Shah seemed to be pleased with the situation and invited me to be his guest at the races on the Turkmen steppe at Bandar Shah a week later.

I myself was not so confident. I knew we had a way to go before the difficulties were overcome. In particular, there was a place near Miånkola where the risk of a major landslide was very high. Several minor landslides had already occurred at this site before we arrived. It was initially intended to take the line across the protruding slope in a cutting, this was revised to using a cut-and-cover tunnel. However, nature itself had its own ideas. Before the Tunnel was completely finished, the ground on either side of the line pushed in on the half-finished tunnel walls. The walls were strengthen by timber frames but they moved like cardboard.”

“We dismissed the sub-contractor and took on the work ourselves. We had to undertake new excavations and started to build a new tunnel. As we were doing so, we discovered that the ground was still moving. It was about 500,000 cubic metres of material and it was still moving at about 2cm a day!

taking the railway through this “floating” soil mass was, of course, impossible. We worked out where the so-called “sliding layer” was located, and introduced drainage tunnels that followed this layer, this eventually dried and anchored the soil mass. The tunnel walls were made extra strong and the foundations were taken down to solid ground beneath the Sliding layer – 7 metres down. A couple of thousand men worked day and night for many months at Miánkola, and in addition to our lead engineer at the site, Moses, we sent one of our best people up there, “Shanghai”-Pedersen, a man who had many years engineering experience in China (hence his nickname) and good experience of working in difficult ground.”

“But problems rarely come alone. Immediately after we solved one problem, another arose. This time it was a little further south. Here, too, we worked our way through unstable soils, and between Christmas and New Year some violent landslides occurred, which completely closed a large excavation and buried tunnel workings.”

“Engineer Saxild elsewhere at this time, and the situation was critical. Pressure was placed on Kampsax, and the Shah became impatient. In reality, the whole contract hung in a thread. However, Engineer Kayser, who was the Chief Engineer in Saxild’s absence, retained his composure, and together he and I went up to Miånkola accompanied by Chief Engineers Blach and Park, and the Engineers from the nearest Sections, Austrian Rabcewics and Dane Lehmann. In short shrift, we worked out remedial action, the implementation of which we knew we could guarantee to the Government.”

“But it was not just about purely technical matter,” Engineer Wright continued, “it was very urgent, because the Shah wanted progress ,but was also participating in intrigue, along with others, seeking to paralyze Kampsax at the start of our work on the line. It became a matter of pride for us, that we manage the Miånkola section as well as possible. In order that theses difficulties did not slow the work, … we built a temporary bridge along the river bank, on which the track could by-pass the problem section.”

“These were exciting months, and I admit there were times when it was quite nerve-wracking. The awareness that 500,000 cubic metres of earth was relentlessly slipping downhill, while over a thousand men worked around the clock to prevent a violent landslide from destroying the new Tunnel, and handling the Shah’s increasing impatience with progress, was not always good for one’s rest at night. But out on the line, there was no nervousness on display. Moses and “Shanghai” took care of our affairs, and although the ground moved significantly before we had it stabilized, the work was completed without major mishap. The Shah was gradually reassured by watching progress, despite all the difficulties.”

“Incidentally,” he said, “our return trip to Tehran was pretty dramatic. South of Miånkola we could see that heavy grey clouds were hiding the Elbruz mountains to the south, and we had not driven long before it started to snow. In the aftermath, there was a hugh snowstorm, and by Sorkhabad, only around 40 km south of Miånkola, the road was completely blocked by snow. It was of the utmost importance for us to get to Tehran quickly to present our plans to the Government. We had to leave the cars, and with great difficulty, we pushed through the snowdrifts on foot to reach Abbasabad, where Rabcewics was living at that time. It was a 10km walk in a strong snowstorm, and frankly we were more dead than alive when we arrived.”

“We had to wait at Abbasabad until the blizzard had subsided and the roads through the Talat Valley had been made fairly passable. With great difficulty, the driver dug out the cars at Sorkhabad, and all available crews were assigned to removing snow, so that we could continue the journey.”

“But it went slowly. After a few days of waiting in Abbasabad, we started driving up towards Gaduk. But again, at Churab, we had to give up, as the Gaduk Pass was completely blocked by the snow. We stayed with Kirchmair, an Austrian Kampsax Engineer who lived in the Churab Valley, while 200 workers were sent to move the snow in the Pass.”

“Up at the Pass itself there was a sad accident during the snowstorm. A caravan had been surprised by the snow at night and had tried to reach the village of Gaduk, which was nearby. Only 200 metres from the village, people, camels and donkeys could not continue and froze to death.”

“I do not know how cold things were on this occasion,” engineer Wright continued, “but several times I have experienced the thermometer showing more than 30 degrees of frost up in the highlands. Moreover, one of the officials of the Iranian Government almost shared the fate of the people in the caravan. It was Chief Engineer Chagakhi, who was on his way to Miånkola to look at the problem of the big landslides. Between Firuzkuh and Gaduk, he got stuck in the snow, and he was fully engaged in digging out when we finally reached Churab. Once he had got rid of the snow and heard what we had to say about the prevailing conditions, he turned round and drove back to Tehran with us.”

“The difficulties at Miånkola were eventually overcome, and when the Shah saw how the work proceeded according to the plan we had set, he relaxed a little. But,” concluded Engineer Wright, “Miånkola is a chapter in the history of the construction that we will never forget,.”

2. The additional material below is also translated from the original Danish. It continues the account by Ingolf Boison about the filming of a hour long documentary. The original Danish text can be found on the SJKPostvagen platform. In some places the text has been slightly abridged. [1] Chapter 10 is immediately below. [1: p93-107]

Chapter 10: Shahernes Shah

“Government officials must show fidelity, impunity, energy and activity. They must endeavour to make the people wise, strong and powerful and to care for their welfare in accordance with my wishes.”

It was not an empty phrase when Reza Shah uttered these words at his coronation in April 1926 at Golestan Palace in Tehran. He needed the complete commitment of his officials to implement the huge reform program he had planned so as to improve the country.

Before he began his speech, the Prime Minister had placed the golden jewel-studded “Pahlevi Crown” on his head … and now sitting on Nadir Shah’s famous peacock throne, he told the important people gathered around him, how he expected then to develop the country. The time of ancient Persia was now over. From a ‘quantite negligable’ the country would now again become a state to be reckoned with, and occupy a place worthy of its historical past.

Reza Kahn, as he was previously known, was born in 1878 in the province of Mazanderan as the son of a reputed officer. Through a long life as a soldier, he had served his country and seen how it had gradually lost its independence and sunk into a sphere of interest divided between Russia and Great Britain. By the end of the previous World War he had become the Colonel of the North Persian Cossack Brigade, where he had been serving since he was 22 years old. It is said that when the English General Ironside served for a time as an instructor of the Cossack Brigade, he persuaded Reza Khan – to whose talents he was not blind – to promise that he would not revolt against the ruling Shah. However, as conditions in Persia became increasingly miserable, Reza Shah decided to organize a coup against the incumbent government, and in 1921, when the foreign political situation created the opportunity, he gathered his forces in Kazvin and went to Tehran. The capital immediately surrendered and a new Government was deployed. Reza Khan became Commander-in-Chief of the Army, later Minister of War and in 1923, Prime Minister. The country’s nominal ruler, Ahmåd Shah, who belonged to the Kadjar dynasty, stayed in Paris, where he … seemed not to care about what happened in Persia.

Reza Shah had not forgotten his promise to General Ironside, but when Ahmåd Shah, despite numerous requests, refused to leave Paris, Reza Khan wrote to General Ironside, explaining to him the disastrous position for the country and asking to be released from his promise. The English General agreed, and after another vain request to the Shah to return home, Reza Khan let him resign, after which he himself was made ruler and ascended the throne as Shahernes Shah.

And then Reza Shah went on to reorganize his country. He had initiated some cultural and material reforms immediately after the coup in 1921, but now came the serious step towards realizing the great plans he had laid for the country’s future. The first thing he did was to modernize the Army and create peace in the country. The judiciary was changed to accord with more European, democratic patterns and finances were brought under the direction of an American expert, Dr. Millspaugh. Iran is now one of the few countries that is virtually free of foreign debt, and even major reforms have been implemented without the need for borrowing.

It has already been mentioned how the funds for the railway construction were provided through a tax on Tea and Sugar monopoly. … Another important factor in Iran’s financial status, the Oil Concessions, must be mentioned.

In the business world, new modes of operation and methods have been introduced, modern factories are popping up around the country, and the animal in front of the plough is gradually being replaced by the tractor. But this entire reformed program would not be possible without a radical improvement in the means of transport and a thorough enlightenment among the people. Iran’s 15-16 million Inhabitants in a country of more than 1.6 million square kilometres (an area 36 times the size of Denmark) should now be closer to, and get easier access to, the country’s products. Reza Shah’s plan was that modern roads and a railway across the country had to replace the old Caravan Roads. And it happened. In 1937, over 20,000 km of roads were built, and work on the Trans-Iranian Railway was so advanced that it was expected its inauguration would be celebrated in advance of the six years allocated for its construction.

Within the cultural realm, development under Reza Shah’s rule has been of an almost explosive nature. In 1923, there were 612 schools throughout Iran. Ten years later, that number had risen to 5339 — plus 22 kindergartens! School attendance is now required for all children between the ages of 7 and 13, and in the village schools, agricultural subjects are also taught during the final school years. In the next generation, illiteracy will become a rarity in Iran. In Tehran, in addition to several modern schools, a large university has now been built with six faculties and a number of other higher education institutions.

For Iranian Women, the 1930s have transformed their existence. From the former secluded life of the Harem, where only the Lord of the House may come, and where any form of knowledge acquisition was considered inappropriate, they have now stepped into life as free and equal members of the community.

Formerly, when an Iranian woman was about to go outside the walls of the home, she was tightly veiled in the so-called Tchådor, a large – as a rule black – piece of clothing that concealed her from head to toe, and which was either provided with a narrow wire or horsehair net in front. Only her eyes were visible.

When the “veil” was removed, it was a breach of centuries of tradition, an event one would expect to shake the Iranian community in its foundations. But the Shah had wisely prepared the ground for several years. He knew that the Priesthood would fanatically oppose the plan, and allowed the development to happen gradually.